-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2020; 10(1): 1-7

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20201001.01

Gender Differences in Learning Strategies and Academic Achievement among Form Three Secondary School Students in Nairobi County, Kenya

Josephine Mutua, Syprine Oyoo

Department of Educational Psychology, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Josephine Mutua, Department of Educational Psychology, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In Kenya, like the other nations of the world, academic achievement is associated with individual and national development. However, poor academic achievement especially in the Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education has persisted over the years (2015 – 2018). Therefore, this study sought to establish gender differences in learning strategies and academic achievement among form three students in Nairobi County, Kenya. Explanatory sequential mixed methods design was adopted. Purposive, stratified, and simple random sampling procedures were used. A sample of 488 participants was selected from 10 public secondary schools. Questionnaires and interviews were used to collect data. The study found significant gender differences in rehearsal learning strategy and elaboration learning strategy. However, there were no significance gender differences observed in organization learning strategy. The qualitative findings were in tandem with the quantitative results. In conclusion, the significant gender differences in the different learning strategies implies their importance in the teaching learning process. Therefore, the study recommended that, teachers, parents and all stakeholders in education create an enhancing environment to foster the development of academic mindsets among secondary school students.

Keywords: Gender Differences, Learning Strategies, Academic Achievement, Secondary School Students

Cite this paper: Josephine Mutua, Syprine Oyoo, Gender Differences in Learning Strategies and Academic Achievement among Form Three Secondary School Students in Nairobi County, Kenya, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 10 No. 1, 2020, pp. 1-7. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20201001.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Globally, education is important for personal, social and economic development of nations. It is the key to finding great characters hidden in every individual. However, poor academic achievement has long been an extremely complicated and vexing problem in all the countries of the world. For instance, in Kenya, academic achievement being a critical enabler in the realization of the Big Four Agenda (Food security, Affordable housing, Manufacturing, and Universal health care coverage) especially among Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) students has been declining over the years (2015 – 2018). This has attracted and continues to attract a lot of research to unravel the causes of this poor academic achievement. There are numerous causes of poor academic achievement among them being gender differences in learning strategies and academic achievement.Worldwide, gender equity has remained a major concern especially among academics and policy makers. Usually the main focus is on the role of male and female in the psychological, political, social and economic, religious, scientific and technological development of nations. According to UNESCO (2019), despite the unprecedented progress in expanding school enrollment over the last decades, the achievement of gender parity in formal schooling, inequalities among and within countries remains an issue of concern. According to Ormrod (2015), learning involves the formation of mental representations or associations. This is the view of cognitive psychologists who believe that, for learning to take place there must be an internal mental change unlike the behaviorists who emphasize on external behavior change. Therefore, learning strategies are a series of deliberate behaviors, thoughts and actions that the learner engages in during learning to influence the encoding process (Ormrod, 2015). In view of the current study, learning strategies are contextualized as those strategies that are directly involved with the encoding and retrieval of information in the long term memory (Pokay & Bloomfield, 1990). There are several cognitive learning strategies that affect long-term memory storage including selection, rehearsal, meaningful learning, elaboration, organization, and visual imagery (Ormrod, 2015). Many researchers have categorized these strategies into two. These include surface level strategies and deep processing strategies (Zusho & Pintrich, 2003; Pokay & Bloomfield, 1990). The surface level strategy includes rehearsal learning strategy which focuses on memorization and recall of facts. The deeper processing strategies include elaboration learning strategy and organization learning strategy. The elaboration learning strategy focuses on extracting meaning, summarizing or paraphrasing. It also involves using knowledge acquired earlier on to interpret and expand on new material (Ormrod, 2015). The organization learning strategy involves finding connections and interrelationships within a body of new information for long-term memory storage. This involves creating an outline of the major topics and ideas or creating a graphic representation of the information to be learned for example use of maps, flow charts or pie charts. Reardon, Fahle, Kalogrides, Podolsky, and Zarate (2018) conducted a study on gender gaps in the United States school districts and reported that achievement gender gaps existed among district schools. On the same vein, Sindik (2011) conducted a study on gender differences in the use of learning strategies in adult foreign language learners at the American College of Management and Technology in Dubrovinik. The study reported significant gender differences in the use of learning strategies. Similarly, Fergusson and Horwood (1997) on a study on gender differences in educational achievement in a New Zealand birth cohort reported a statistically significant gender differences in academic achievement. Moreover, in Nigeria, Igbudu (2015) conducted a study on the influence of gender on students’ academic achievement in government subject in public secondary schools in Oredo Local Government area of Edo State. The study reported significant gender differences in academic achievement with females performing better than males. Similarly, Oludipe (2012) conducted a study on gender differences in Nigerian Junior Secondary Students’ academic achievement in basic science using cooperative learning strategy. The study reported no significant differences in academic achievement of male and female students. In Zambia, Mwaba, Kusanthan and Menon (2015) studied gender differences in academic performance of psychology students at the University of Zambia. The study reported that, although gender gap continues to reduce, males tended to perform better than females especially at tertiary level and in traditionally masculine disciplines such as mathematics and physics.In general, much of the research globally, regionally and locally has indicated that, learning behavior is associated with academic achievement at university level but there is limited information if any on the impact of specific learning strategies on academic success as well as gender differences therein. Therefore, in the current study, the researcher examined gender differences in learning strategies and academic achievement among form three students in Nairobi County, Kenya.

2. Statement of the Problem

- Poor academic achievement among students in KCSE examination in Nairobi County has been declining over the years (2015 – 2018). For instance, in 2016, those who obtained between grade D and E were 58.09%. These candidates with low grades do not have many options given the tight race for professional courses and employment. In addition, the overall performance of Nairobi County has been below the national average. When students fail, the parent’s levels of stress go a notch higher as they try to cope with the increasing economic demands in finding alternative courses for their children. Furthermore, poor academic achievement is a threat to the realization of the Big Four Agenda since it is key for personal, social and economic development of the country. Therefore, there was a need for a further study on some of the causes of poor academic achievement among secondary school students. Based on the background to the study, the majority of the studies done in developed countries have reported gender differences in learning strategies and academic achievement (Igbudu, 2015; Oludipe, 2012; Mwaba, Kusanthan & Menon, 2015; Reardon, Fahle, Kalogrides, Podolsky, & Zarate, 2018; Sindik, 2011)). In addition to being done in countries with different systems of education and backgrounds, these studies focused on university and college students with few studies focusing on secondary school students. Therefore, there was a gap at the secondary school level within the African context. In Kenya, related studies have not addressed the issue of gender differences in learning strategies and academic achievement. Therefore, the central problem of this study was to examine gender differences in learning strategies and academic achievement among form three students in Nairobi County.Purpose of the StudyThe purpose of this study was to establish whether there were gender differences in learning strategies and academic achievement among form three students in Nairobi County, Kenya. This was important as it could shed more light into measures aimed at reducing gender parities in academic achievement of boys and girls and therefore the objective of the study was to establish gender differences in students’ learning strategies and academic achievement.

3. Literature

- Gender Differences in Students’ Learning StrategiesStudies have presented mixed results regarding gender differences in learning strategies use. Sindik (2011) conducted a study on gender differences in the use of learning strategies in adult foreign language learners at the American College of Management and Technology in Dubrovinik. The study aimed at determining gender differences in the application of certain types of learning strategies. A survey design and a sample of 181 respondents (72 males, 109 females) learning German, Spanish, French and Italian. The results revealed significant gender differences in the use of learning strategies, where the female sex more frequently used all types of learning strategies. This study was done in the USA with college students, the current study in Kenya involved secondary school students to compare the findings.In another study, Ruffing, Wach, Spinath, Brunken, and Karback (2015), investigated gender differences in the incremental contribution of learning strategies over general cognitive ability in the prediction of academic achievement in German. Using a correlational research design and a sample of 461 students, results revealed that, general cognitive as well as the learning strategies, effort, attention, and learning environment were positively correlated with academic achievement. Male students more often relied on relationships and critical evaluation, whereas female students used all remaining strategies more often. This study utilized a correlational research design while the current study utilized explanatory sequential mixed method design in order to get an in-depth understanding of the study results.Similarly, Simsek and Balaban (2010) examined learning strategies use at Anadolu University in Turkey. One of the objectives of the study sought to establish if there were significant gender differences in learning strategies use of undergraduate students. An independent samples t-test was conducted and results revealed that, female participants were more effective in selection and use of appropriate learning strategies. These findings were consistent with those by Ghiasvand (2010) on the relationship between learning strategies and academic achievement of high school students in Iran. The study sought to compare learning strategies use between under achieving students and upper achieving students. The study utilized a correlational research design and a sample of 501 students from grade 1 to 3 in Qazvin Province. Data was collected using Learning and Study Strategies Inventory. An independent samples t-test revealed that, upper achievers used more learning strategies than lower achievers. More specifically, girls used more learning strategies than boys. These studies involved Asian undergraduate students and primary children respectively. The current study involved public secondary school students to find out if there were gender differences in learning strategies use.Inconsistent findings were found by Balam (2015) in a study on study strategies and motivation of 139 post graduate students (40 males, 99 females) at South Eastern University. The Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) was administered. A 2 x 9 mixed ANOVA were conducted to examine differences between male and female students with regard to motivation and learning strategies. Results revealed no significant gender differences between male and female students with regard to learning strategies. The fact that this study used post graduate students and no gender differences were reported, there was need for a study in another setting to find out if gender differences existed. The current study in Kenya involved secondary school students to compare the findings.The findings among African samples presented mixed results with regard to gender differences in learning strategies and academic achievement. In Nigeria, a study by Anyachie and Anyodike (2012) investigated the effects of self-instructional learning strategy on secondary school students’ academic achievement. Using a quasi-experimental research design and a sample of 131 (66 females, 65 males) secondary school students. The effect of gender on achievement was not significant, although a significant interaction effect was observed between gender and learning strategy use. The male participants in the experimental group significantly performed better than their female counterparts. However, it is important to note that, in the control group that was not trained on strategy use, girls performed better than boys from the pre-test to post test. This study utilized a quasi-experimental research design while in the current study, an explanatory sequential mixed method design was used to compare the results.A study in South Africa by Robertson (2012) in the University of Pretoria investigated learning styles and learning strategies among university students. One of the study objectives hypothesized that, there were no significant gender differences between male and female students in learning strategies use. The study found no significant gender differences between male and female students in relation to academic achievement. However, some significant gender differences were reported between males and females in relation to learning strategies. More specifically, female participants used organization learning strategies more than male participants. The results of this study could not be generalizable to other populations since they were based on only one university. The current study addressed this concern by involving 10 public secondary schools in Nairobi County to establish if there were gender differences in learning strategies and academic achievement.Available studies in Kenya had inconsistent findings. For example, in a study by Mutweleli (2014) among public secondary school students in Nairobi County, significant sex differences with respect to rehearsal and organization learning strategies were reported. Specifically, more boys than girls endorsed use of rehearsal and organization learning strategies. However, Dinga (2011) in a study on cognitive strategy use with a sample of 785 primary school pupils in class five and seven in Kisumu Municipality found no significant sex differences with regard to cognitive strategy use. These inconsistent findings made the current study necessary to establish if there were gender differences in students’ learning strategies among public secondary school students in Nairobi County. Summary of Literature Reviewed and Gap IdentificationFrom the literature reviewed, the majority of the studies have presented mixed results regarding gender differences in learning strategies and academic achievement. However, most of these studies were done in the developed countries and they examined gender differences in students’ learning strategies with other variables. Furthermore, these studies were based on university, college and elementary school students. Only few studies focused on secondary school students. In addition, these studies presented methodological gaps and the results were inconsistent and inconclusive. In the African educational set up and more specifically in Kenya, none of the reviewed studies examined gender differences in learning strategies and academic achievement using the triangulation method. Therefore, this study used an explanatory sequential mixed method design to find out whether there were gender differences in learning strategies and academic achievement among public secondary school students in Nairobi County, Kenya.

4. Research Design

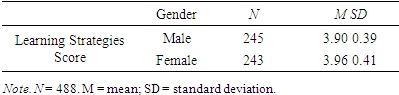

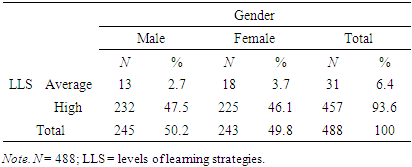

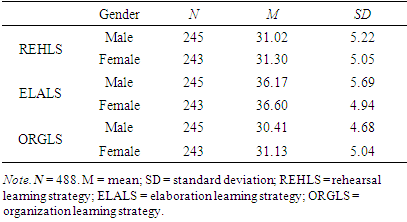

- The researcher adopted an explanatory sequential mixed method design. This design involves two phases of data collection and analysis. In the first phase, quantitative data was collected and analyzed, with an intention of first addressing the study objective. It was then followed by a second phase which involved collection and analysis of qualitative data in order to explain in more detail the quantitative results (Creswell, 2018). For the quantitative data, the researcher used predictive correlational research design which is a form of correlational research design. According to Fraenkel, Wallen, and Hyun (2015), a correlational research design describes the degree to which two or more quantitative variables are related and there is no manipulation of such variables hence its suitability for the current study. For the qualitative data, in-depth interviews were conducted on a purposively selected number of participants in order to get personal perspectives of the participants regarding learning strategies. The purpose of the qualitative phase was to explain further the earlier obtained quantitative results. Therefore, explanatory sequential mixed method research design was considered suitable for this study since it allows the exploration of relationships between variables in depth.ParticipantsThe study comprised 488 form three students (243 girls, 245 boys) from 10 public secondary schools in Nairobi County, Kenya. The participants age ranged between 15 – 23 years (M = 3.96, SD = 0.41 for girls and M = 3.90, SD = 0.39 for boys).MeasuresThree research instruments were used in this study. They were a student’s questionnaire, a pro forma summary of student’s academic results and an interview schedule. The questionnaire comprised of two parts. Part I (items 1 – 5) consisted of student’s demographic information regarding their age, gender and type of school. Part II consisted of (items 1 – 25) on learning strategies. The researcher adapted scales from Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) to collect data on the participants’ learning strategies. The MSLQ was developed by Pintrich, Smith, Garcia, and Mckeachie (1991). It is a self-report instrument which measures students’ motivational beliefs and strategy use. This instrument is completely modular as it allows the researcher to use the scales together or individually depending on the specific needs. Hence, in the current study, three subscales of learning strategies were used which included: rehearsal learning strategy, elaboration learning strategy and organization learning strategy. The questionnaire comprised (items 1-25) of students’ learning strategies. These 25 items were divided into three subscales. Rehearsal learning strategy was measured by the summated score of responses to the 8 items on the rehearsal subscale of MSLQ. Scores ranged from 8 to 40 with low score indicating high endorsement of the construct and high score indicating low endorsement of the construct. Elaboration learning strategy was measured by the summated score of responses to the 9 items on the elaboration subscale of MSLQ. The scores ranged from 9 to 45 with low score indicating high endorsement of the construct and vice versa. Organization learning strategy use was measured by the summated score of responses to the 8 items on the organization subscale of MSLQ. The scores ranged from 8 to 40 with the low score indicating high endorsement of the construct and vice versa. The three were based on a five point summated rating scale with responses ranging between 1 (not at all true of me) and 5 (very true of me) for positively worded items and vice versa for negatively worded items. Scores for the individual scales were computed by taking the mean of the items that made up the scale.

5. Results

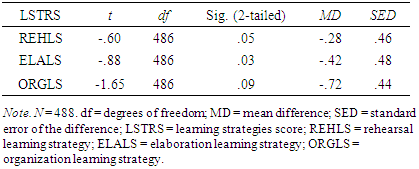

- Gender Differences and Learning Strategies The respondents’ scores in learning strategies use were analyzed to find the mean and the standard deviation of the scores. The results are presented in Table 1.

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. Qualitative Data Analysis

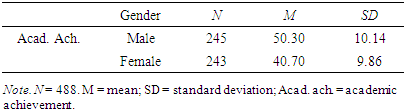

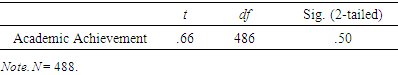

- The purpose of qualitative data analysis in the current context was to provide more insight into the quantitative results (Creswell, 2018). The intent of the qualitative findings was to get the specific personal perspectives of the participants in reference to students’ learning strategies and academic achievement. The qualitative findings were in tandem with the quantitative results obtained earlier. Although boys performed better than girls, this was not statistically significant. In addition, a majority of the interviewed respondents endorsed elaboration and rehearsal learning strategies than organization learning strategy. Girls endorsed more of these learning strategies than boys. On the other hand, more boys than girls were better in organization learning strategy which is a deeper learning strategy. This organization learning strategy involves creating an outline of the major topics and ideas or creating a graphic representation of the information to be learned for example use of maps, flow charts or pie charts. This could explain the reason why there were no significant gender differences when the interviewed participants were followed through their academic achievement results. From the interview findings, a majority of the interviewed participants did not seem to understand what these learning strategies were hence they did not have any preferred learning strategy. This implied that, the knowledge of learning strategies to both boys and girls was very important as this could enhance their academic achievement.

7. Discussions

- The results of the current study revealed that, there were significant gender differences in rehearsal learning strategy and elaboration learning strategy. However, there were no significant gender differences observed in organization learning strategy. Girls were found to endorse use of rehearsal and elaboration learning strategies than boys. Moreover, there were no significant gender differences between boys and girls in academic achievement. These findings corroborated those by Sindik (2011) who reported significant gender differences in the use of learning strategies, where the female students, more frequently used all types of learning strategies. In another study, Ruffing, Wach, Spinath, Brunken, and Karback (2015) investigated gender differences in the incremental contribution of learning strategies over general cognitive ability and reported that general cognitive as well as the learning strategies, effort, attention, and learning environment were positively correlated with academic achievement. Male students more often relied on relationships and critical evaluation, whereas female students used all remaining strategies more often. Consistent findings were reported by Simsek and Balaban (2010) who examined learning strategies use at Anadolu University in Turkey. The study reported that female participants were more effective in selection and use of appropriate learning strategies. Similar findings were reported by Ghiasvand (2010) on the relationship between learning strategies and academic achievement of high school students in Iran that girls used more learning strategies than boys. On the same vein, Anyachie and Anyodike (2012) reported that, even though the effect of gender was not significant, when participants were trained on strategy use, males in the experimental group significantly performed better than their female counterparts. However, they pointed out that, female participants in the control group performed better than their male counterparts from the pre-test to post test. This again implies that girls embraced more the use of learning strategies than boys. These findings are also aligned to those by Robertson (2012) who reported significant gender differences between males and females in relation to the subscales of learning strategies. More specifically, female participants endorsed more the use of organization learning strategies than their male counterparts.Inconsistent findings were found by Balam (2015) in a study on study strategies and motivation at South Eastern University. The study found no significant gender differences between male and female students with regard to learning strategies. Contrary to the current study, Mutweleli (2014) reported significant sex difference in rehearsal and organization learning strategies. More boys than girls endorsed use of rehearsal and organization learning strategies. Inconsistent results were also reported by Dinga (2011) who found no significant sex difference with regard to cognitive strategy use.

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The study found that, were significant gender differences in rehearsal learning strategy and elaboration learning strategy. However, there were no significant gender differences observed in organization learning strategy. Girls were found to endorse use of rehearsal and elaboration learning strategies than boys. Moreover, there were no significant gender differences between boys and girls in academic achievement. This could be due to the efforts being made to promote the right to education for all (UNESCO Priority Gender Equality Action Plan 2014 – 2021). Therefore, the study recommended that, teachers, parents and all stakeholders in education create an enhancing environment to nurture the development of learning strategies of both boys and girls to enhance academic achievement among secondary school students.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML