-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2019; 9(5): 135-144

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20190905.03

Resilience Effects on the Self-Development of Secondary School Adolescents in Buea, Cameroon

Joseph Lah Lo-oh1, Anita Emenkeng Atemnkeng2

1Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, The University of Bamenda, Bamenda, Cameroon

2Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Buea, Buea, Cameroon

Correspondence to: Joseph Lah Lo-oh, Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, The University of Bamenda, Bamenda, Cameroon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

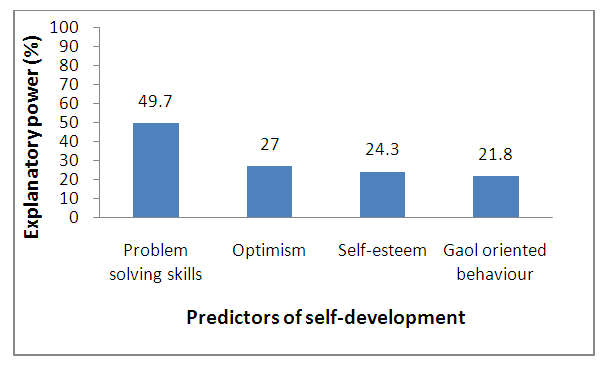

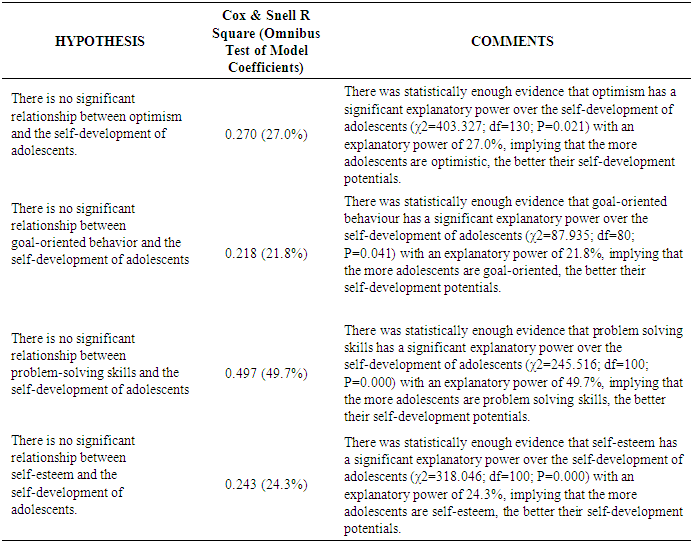

This study investigated resilience effects on the self- development of adolescents in some schools in Buea, Cameroon. It was based on the premise that adolescents go through a series of adversities that greatly hinder their development. A major contention in this study was therefore that resilience could serve as a major framework for the self-development of school-going adolescents in Buea. It was hypnotized that resilient behaviours such as optimism, goal-oriented behavior, problem-solving skills and self-esteem were likely measures that could influence the self-development of school adolescents. The descriptive design was adopted for the study with a questionnaire used to collect data from a randomly selected sample of 357 students. Data collected were subjected to both descriptive and inferential statistics. The Spearman’s rho correlation was used to test the predictability of resilience over self-development. Findings showed that problem solving skills had the most predictive power over self-development (χ2=245.516; P=0.000) with a predictive power of 49.7% followed by optimism (χ2=403.327; P=0.021) with an explanatory power of 27.0%, then self-esteem (χ2=318.046; P=0.000) with an explanatory power of 24.3% and finally goal-oriented behaviour had the least predictive power (χ2=87.935; P=0.041 with an explanatory power of 21.8%. These findings showed that resilience is an intrinsically grounded attribute of an individual’s own wellbeing that directs one’s movement towards self-developmental pursuits and endeavours. With resilience therefore, adolescent students have the capacity to persist even when they are faced with arduous adverse circumstances with the strength of limiting their journey through life. With it, they embrace life’s challenging circumstances with great might as they benefit from inbuilt resilient capacities to surmount adversities and remain on track towards desired futures.

Keywords: Adolescents, Resilience, Optimism, Goal-oriented behaviour, Problem-solving skills, Self-esteem, Self-development

Cite this paper: Joseph Lah Lo-oh, Anita Emenkeng Atemnkeng, Resilience Effects on the Self-Development of Secondary School Adolescents in Buea, Cameroon, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 9 No. 5, 2019, pp. 135-144. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20190905.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Globally many adolescents face adversities and the extent of such adversities appears to be increasing (Goldstein & Brooks, 2013). The nature and extent of these adversities are reported in annually updated reports (for example, UNICEF's State of the World's Children reports (UNICEF, 2013). Among others, poverty, chronic parental discord, violence, experiences of trauma, disability and ill health place adolescents at substantial risks of negative developmental outcomes. In 2010, for example, 60% of all South African children lived below the poverty line (that is., on less than $50/month), 3.8 million children were orphaned (80% of which were of secondary school-going age), and 0.5% (around 90 000 children) were living in child-headed households (Smith & Carlson 2012). Growing up with such challenges therefore threatens adolescent positive self-development. Also, when schools and communities fail in their role of providing opportunities for growth and development, they inadvertently contribute a significant share to the battery of adversities young people are exposed to. Resilience becomes an important factor in the positive development of youth faced with these adversities. Benson (1997) postulates that the term “resilience” indicates a paradigm shift from focus on risk factors in individuals to focus on the strengths or likely strengths they may be capable of disposing in the midst of the plethora of adversities. Some research also argues that a resilient individual is stress-resistant and less vulnerable despite experiences of significant adversities (e.g. Luthar, Cicchetti & Becker, 2000). According to Benson (1997), the concept of resilience comes from physics and describes a quality of a material to regain its original shape after being bent, compressed or stretched. With regard to adolescents, it can be construed as an individual’s ability to regain his/her shape after going through crises or adversities, the ability to cope and do well in life in spite of having had to face a number of difficulties or challenges (Grotberg, 1999). In the context of exposure to significant adversity, resilience therefore is both the capacity of individuals to navigate their way to the psychological, social, cultural, and material resources that can sustain their well-being and individual and collective capacities to negotiate for these resources which must be provided in culturally meaningful ways (Ungar, 2011). It requires that individuals have the capacity to find resources that bolster well-being, while also emphasizing that it is up to families, communities and governments to provide these resources in ways individuals value.Resilience is regarded as a constituent of positive self-development, as such, it is a defining condition for positive youth development (e.g. Werner & Smith 2005). Resilience also constitutes the asset-building model and the inclusiveness model of positive youth development (Allen, 2000) which in the most part maintains that irrespective of adversities that individuals may be exposed to, they could exploit some personal resources, such as resilience or agency to navigate through the challenges and still lead positive and productive lives during childhood, adolescence and the adult years. For instance, the asset-building model posits that resilience is one of youth’s internal assets for constituting positive self-development and as such, the development of resilience is perceived as a process of asset building. In this connection, resilience would have an association with similar assets or aspects of positive youth development such as agency, optimism, controllability, conflict resolution, self-regulation, self control, problem-solving and in particular, self-development.

1.1. Literature Review

- The notion of self-development is becoming a key developmental task in the human life course, and even more so during the early years of life, in childhood and adolescence. Studies addressing self-development have often paid attention to personal characteristics often sourced by individuals in order to successfully navigate their lives (e.g. Smith & Carlson, 2000). The main argument is that positive developmental outcomes are personally pursued especially when social systems have failed to provide a healthy surrounding environment for positive and productive development. Seen in that light, self-development perspectives, therefore encourage each individual to become personally, emotionally, socially and physically effective to live healthy, safe and fulfilled lives; to become confident, independent and responsible citizens, making informed and responsible choices and decisions throughout their lives, irrespective of any challenges that may stand in their way (Hawkins, 2002). Self- development involves continuous learning to take responsibility for one’s own life or take one’s life and destiny into one’s own hands (Lo-oh, 2017). In this wise, an individual’s knowledge and experience becomes his/her personal wealth or asset that should never be wasted or dumped. Among the many personal characteristics for self-development is resilience.Being a relatively new construct in positive psychology in general and in positive youth development in particular, resilience has been approached variously, though with unifying meaning around coping with or overcoming adversity, disruptive, stressful or challenging life circumstances in ways that provide individuals with additional protective factors and coping skills (Richardson, 2002). In line with this, Gu & Day (2006) noted that resilience is the ability to bounce back, to recover strengths or spirit quickly and efficiently in the face of adversity. Similarly, Greene, Galambos & Lee (2003) viewed it as the ability to overcome adversity and be successful in spite of exposure to high risk. Meanwhile Higgins (1994) viewed resilience as the process of self-righting or growth, the capacity to bounce back, to withstand hardship, and to repair oneself. As a construct of positive youth development, resilience is often studied and understood in two dimensions: exposure to adversity or risk factors and protective factors or positive developmental outcomes of adversity (Luther, Cicchetti & Becker, 2000). That is why Masten (2007) maintained that resilience would also refer to people who from high risk groups or challenging and difficult life circumstances have had better or more positive developmental outcomes than expected, better adaptations despite stressful experiences (common) and better recovery standards from trauma than expected. The study of resilience for self development becomes very relevant when we know that young people today, especially those in deprived regions of the world, like Africa, are more exposed to challenging developmental life trajectories than ever before. In this connection, child and youth research in Africa has underscored a litany of adversities of all kinds, ranging from childhood problems such as abuses of all kinds, neglect, poverty, nutritional problems such as malnutrition, disease, death to adolescent problems such as early marriage and pregnancy, depression, violence, alcohol and drug use/abuse, family disharmony, homelessness and under-scholarisation (e.g. Nsamenang, 2007; Lo-oh, 2009). Again, we find that more and more today, adolescents are succumbing to more emotional, social and psychological problems and disorders; struggling with obesity, low self-esteem and other unhealthy life conditions today than any generation gone by.Yet many affected individuals still make it successfully and even more productively to their futures. In fact, many of the most successful, competent and influential people in Africa today are doing so because of adverse life circumstances in their childhood (Lo-oh, 2017). With childhood adversities, they developed among others, resilience or protective factors with which they overcome setbacks, disappointments or failure to build productive lives for themselves. But this also suggests that parenting behaviour has to be one that inculcates resilience. For example, Benard (2002) worked with children considered to be at risk for many years. Rather than focusing on what was wrong in these children’s lives, she explored what was working, and what was helping them to cope with their very dysfunctional lives. Her study and many others of this nature led to the development of protective factors needed for the development of resilience and resilient behaviour (e.g. Burt, 2002). Those considered for this study and to be important for self-development were optimism, goal-oriented behaviour, problem-solving skills or coping skills and self esteem.Early Christian writers identified optimism as one of the most positive essential virtues along with faith and charity (Snyder, 2000). In a similar fashion, historical religious figures such as Martin Luther placed optimism at the same level as love as the core of what is good in life, and felt it was necessary to exhort their followers to hope (Magaletta & Oliver, 1999; Snyder, 2000). Despite these favourable views, various writers throughout history have portrayed it as an evil force. Bacon held similar views about optimism labelling it is an illusion that lacked substance (Snyder, 2000). Contrarily, 20th century research found that a lack of optimism or negative thoughts and feelings were related to poor health, coping and health recovery, suggesting that optimism could have a positive effect on health and wellbeing (e.g. Schwarzschild & Kohler, 2018; Snyder, 2000). And Snyder (1995) found that individual with higher levels of optimism exhibit a higher probability of reaching their goals. In the same light, Murphy (2000) argued that adolescents who believed that they were immensely talented, hardworking, blessed lucky or that they had friends in the right places were said to be optimistic and produced successful life outcomes than those who saw themselves otherwise. Alternatively, Seligman (2009) adopted an attribution model to explain optimism in which he argued that optimistic adolescents explain good life circumstances as having permanent and pervasive causes; hence they are confident and will try harder to achieve positive outcomes in future, albeit the adversities. Again optimistic adolescents make realistic judgment of one’s responsibility when things go wrong; even when they blame themselves for the faults, they do attribute them to temporary, specific and internal causes, which of course can be adjusted.Another of the resilient behaviours or protective factors for self development is goal-oriented behaviour. With it, adolescents can plan their lives and can model them in such a way that they can anticipate life events, such as school completion, employment, marriage and estimate the ages at which they will likely experience them (Crockett & Bingham, 2000). In line with this, Cantor (1990) proposed that as adolescents transition into adulthood, they become more focused on their desires and aspirations for the future and show increased selectivity in goal-directed behaviour. During this period, they also engage in exploratory behaviours that may aid in elaborating their sense of identity, providing information about the self that affects future plans (Eccles, Barber, Stone, & Hunt, 2003). That is why Carver & Scheier (1998) saw goals as actions, end-states or values that individuals see as being either desirable or undesirable and by implication, adolescents try to fit their behaviours into what they see as desirable while staying away from what they see as undesirable. All these require the resilient attribute of goal-directed behaviour. Blakemore & Choudhury (2006) argued that goal-oriented behaviour refers to either of two separate process types: motor processes, that is, organizing action-oriented behaviours towards physical targets; and decision making processes, which select these targets by integrating desire for and knowledge of action outcomes. Therefore, through goal-directed behaviour, adolescents develop an extended future orientation in which they are able to think, dream, and plan for their futures.Masten, Best & Garmezy (1990) posited that the ability to cope effectively with anxiety and stress is a resilient skill which differentiates low-risk from high-risk young people. Effective coping skills, otherwise problem-solving skills influence the individual’s response to stress, which in turn affects the way that individuals deal with conflicts with self and others. Depending on the young person’s problem-solving skills, he/she could either cope with humour, altruism or painful circumstances by focusing his/her attention elsewhere, or he/she could withdraw or simply act out. This view is reinforced by Lewis (1999) who suggested that adolescents who display resilience demonstrate the capacity for solving problems and believing in their own capabilities. McWhirter, Hackett & Bandalos (1998) concur with this but emphasize the resilient adolescent’s ability to consider the consequences of his/her decisions. To this end, Felton & Batoces (2002) found that individual problem-solving skills have potential roles in behavioural health; and that effective, high efficacy problem-solver adolescents use more problem-focused coping strategies, have a stronger internal locus of control, more confidence in their decision making ability and are less likely to be impulsive, ineffective and low-efficacy problem-solvers. It therefore goes without saying that problem-solving skills stand out as a significant resilient behaviour that adolescent could harness to overcome adverse circumstances in order to navigate life courses, especially those that are challenging and problematic. As seen so far, key questions of resilience turn around the individual’s self, his individuality which he/she harnesses to overcome adverse circumstances. Issues of identity and self-concept in general and self-esteem in particular become a significant resilient attribute for consideration, especially for self-development purposes. According to Adams (2010) self-esteem is an evaluation of self-concept that includes one’s feelings towards positive and negative appraisals about an individual’s self. And to Rosenberg (1985) high self-esteem is the feeling of being satisfied with oneself, and believing that one is a person of worth. Similarly, Harter (1999) defined self-esteem as the evaluations that individuals make about their worth and value. With these in mind, self-esteem has been shown to be an indicator of overall wellbeing and is linked to positive psychological and behavioural outcomes for youth (Greene & Way, 2005). Conceptually, self-esteem includes the personal and total feelings of self-value, self-confidence or self-acceptance (Leory, 1996). It is an evaluation of the information contained in the concept of self (King, Meehan, Trim & Chassin, 2006). In the concept of self, people believe that they are talented, successful, worthy and important (Salami, 2010), resulting in positive evaluation. Positive self-esteem is described as accepting, appreciating and trusting oneself entirely as an individual (Salmivalli, Kaukiainen & Lagerspetz, 1999), thereby fostering self-development. In this connection, Coleman & Hendry (1990) found that adolescents with high self-esteem demonstrate a tendency towards being happy, healthy, productive and successful; make more effort towards overcoming difficulties; sleep better at night; have less risks in developing ulcers; and show a lesser tendency towards yielding to peer pressure. Meanwhile those with low self-esteem were found to be worried, pessimistic, and with a battery of negative thoughts about the future. According to Kassin (1998) they, that is those with low self-esteem are characteristic of unsuccessfulness, being nervous, making less effort, and ignoring the important things in life. Against difficult life circumstances therefore, self-esteem, and particularly high self-esteem becomes very compelling. In fact, Yelsma & Yelsma (1998) have argued that adolescents with high self-esteem prefer difficult circumstances, appear to be quite sure of their efforts leading to success, are less sensitive to emotional turbulence and less affected by depression.

2. Method

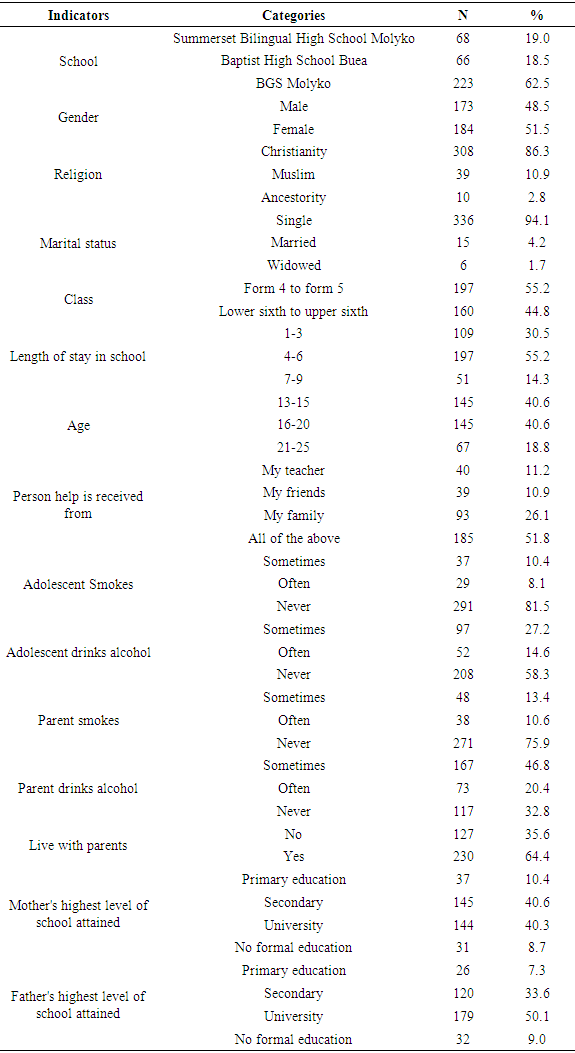

- The descriptive design was adopted for the study; and with it a sample of 357 male (173) and female (184) adolescent students were randomly selected across some three high schools in Buea, Cameroon.

2.1. Sample Description

2.2. Instrumentation

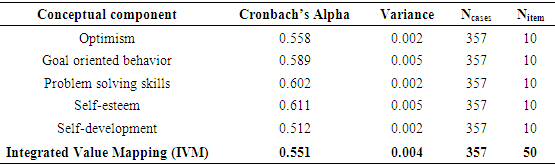

- The instrument used for data collection was a 66 item questionnaire which measured optimism, goal-oriented behaviour, problem-solving skills, self-esteem and self-development. Optimism was measured by 10 Likert scale-type items featuring issues such as adolescents expecting to do better in school even when they fail, expecting the best results in school, never getting easily upset when faced with difficult tasks in school, ascribing importance doing assignments, loving it when difficult assignments are given because they make them learn and so on. Goal-oriented behaviour was measured by issues such adolescents believing that opportunity to do challenging work is important to oneself, planning to try or repeat a difficult task when they fail to complete it, planning to try later, preferring to work on tasks that force them to learn new things, easily giving up when the teacher gives a difficult exercise, feeling discouraged when they make mistakes and so on.Measures of problem-solving skills included amongst other issues adolescents understanding they must find the answer to the problem that the teacher has put before them, assuming that by asking questions to the teacher, they gather information to solve problems, being able to identify the knowledge required to solve a problem, not being discouraged when they do not easily find a solution to a problem and so on. On its part, self-esteem included items such as adolescents feeling angry when someone criticizes them, feeling they will never become great persons in life, having what it takes to socialized with their friends in school, thinking they are a failure, feeling as though they are not good enough for those who care about me, feeling insulted when the teacher rejects their ideas in class and so on. Finally, the dependent variable, self-development was measured by items such as adolescents finding it difficult to introduce themselves in class, finding it easy to stay relaxed and focused even in the presence of pressure, never initiating conversations, rarely doing something in class just out of curiosity, believing that being organised is more important than being adaptable, usually highly motivated and energetic and so on. Analyses showed that problem solving skills had the most predictive value over self-development, with a predictive power of (49.7%) whereas goal-oriented behaviour had the least predictive value with an explanatory power of (21.8%.). Optimism (27%) and self-esteem (24.3%) were also found to have more significant effects on adolescent self-development like problem-solving skills.

|

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Optimism and the Self-Development of Adolescents

- The findings indicated that optimism significantly influences the self-development of schooling adolescents. This implies that the more adolescents are optimistic, the better their self-development effort becomes. This also means that because of optimism, adolescents are more hopeful and confident about their futures which in turn positively influence their efforts towards self-development. This as well means that with optimism, adolescents believe that they can face tough times and challenges of all sorts and still win. This finding is in line with Valle, Gilman & Huebner (2006) who revealed that optimism is a moderator in the relationship between stressful life events, global life satisfaction, and adolescent well-being. In the same vein, Gilman, Dooley & Florell (2006) found that youth with high optimism reported higher academic and psychological adjustment in the face of academic and psychological difficulties. And Snyder (1994) argued that optimism scores were positively correlated with children’s perception of athletic ability, physical appearance, social acceptance and academic achievement; and negatively correlated with depression and its symptoms.Specific findings related to optimism further showed that adolescents believe in a very bright future, they still expect to do better in school even when they fail, and they try to do their exercises no matter how difficult things become. They love when difficult assignments are given because they make them learn. In fact, students agreed that they do not easily get upset when they have difficult tasks in school. In line with this, Seligman (2009) argued that optimistic adolescents perceive good events as having permanent and pervasive causes; hence they are confident and often try to achieve positive outcomes in the future in spite of the adverse circumstances on their way. In addition, optimistic adolescents make realistic judgment of one’s responsibility when things go wrong. Even when they blame themselves for the faults, they attribute such faults to temporary, specific, and internal causes, such as lack of effort which they can adjust (Seligman, 2009). That is why perhaps, Todis, Bullis, Waintrup, Schultz & D’Ambrosio (2001) found that adolescents who are successful are those who had a more optimistic outlook, determination and a stronger future orientation.The present findings also tie with Carver & Scheier (2002) who opined that when confronted with a challenge, optimists are confident and persistent, even if progress is difficult and slow; but pessimists are more doubtful and hesitant. They went further to explain that, adversity is what exaggerates the difference between optimists and pessimists. Optimists believe adversity can be handled successfully, pessimists rather expect disaster. Based on this, Scheier, Carver & Bridges (2001) added that difficulties elicit many feelings, feelings reflecting both distress and challenge. The balance among such feelings differs between optimists and pessimists. Because optimists expect good outcomes, they are likely to experience a more positive mix of feelings. But pessimists who expect negative outcomes, experience more negative feelings—anxiety, sadness, despair and negative future outcomes. In line with these socio-emotional differences, Snyder (1995) found inverse relationships between measures of optimism and depressive symptoms; argued that as hope scores increased among students, scores of depressive symptoms decreased. Finally, optimism was earlier seen as a protective factor in the lives of many adolescents facing stressful life events (Valle, Huebner & Suldo, 2006). In their studies, participants with higher optimism were more likely to report higher levels of life satisfaction a year later. Ciarrochi, Heaven & Davies (2007) also found that optimism diverted youth from participating in risky behaviours such as substance use; and at-risk children who were more optimistic and hopeful had fewer externalizing and internalizing behavioural problems (Hagen, Myers & Mackintosh, 2005).

4.2. Goal-Oriented Behaviour and Self-Development

- When we tested the link between goal-oriented behaviour and the self-development of adolescents, findings suggested that there exists a significant relationship between the two variables. This means that the more adolescents exhibit goal oriented behaviour, the more effort they exert in their self-development. This also implies that adolescents have ambitions and they do not just stay at the level of being ambitious but also make some plans and put in much effort to see that they meet their goals. This relationship reflects Blakemore & Choudhury (2006) who indicated that adolescents develop an extended future orientation in which they are able to think, dream and plan for their futures. In a similar way, Gottfredson (2002) opined that with goal-directed behaviour, adolescent aspirations become more realistic, based on their interests, perceived abilities, and individual characteristics as well as the opportunities available to them. As adolescents gain experience, they develop more self-knowledge (Eccles, Barber & Stone, 2003) which should lead to further refinement of their life aspirations and expectations, albeit life challenges. In this connection, Crockett & Bingham (2000) argued that adolescents can anticipate common events, such as school completion, and estimate the ages at which they will likely experience them. Still in line with this, Cantor (1990) found that as adolescents transition into adulthood, they become more focused on their desires and aspirations for the future and show increased selectivity in goal-directed behaviour. Adolescents’ thoughts about their future selves are important because they presumably influence choices, decisions, and activities, which in turn affect subsequent accomplishments (Nurmi, 2004). He also proposed that adolescents develop goals relevant to their expectations for the future, which motivate achievement.Empirical studies are sparse but provide support for the role of future-oriented cognitions in adolescents’ later life attainment. For example, Messersmith & Schulenberg (2008); Ou & Reynolds (2008) posited that adolescents’ educational expectations predict their educational attainment, and Armstrong & Crombie (2000) concluded that occupational expectations predict occupational attainment. This also reflects Little (2007) who suggested that individuals develop “personal projects” they wish to accomplish, which motivate future attainments.

4.3. Problem-Solving Skills and Self-Development

- Findings showed very strong associations between problem solving skills and adolescent self-development. This implied that the more adolescents had problem-solving abilities, the better their self-development efforts were. This also meant that adolescents believe that they have the ability to look for a way out in every situation that comes their way as well as sourcing means of coping in any adverse situation. Being able to laugh in the midst of difficult situations in turn positively influences their self-development and at the end, they become stronger and even develop more problem solving skills to face greater challenges and still come out victorious. This relationship reflects Werner & Smith (2005) who argued that when coupled with effective problem-solving skills, young people have a positive protective armor against the negative outcomes associated with high-risk life circumstances. Effective problem-solving skills therefore influence the individual’s response to stress, which in turn affects the way that individuals deal with conflicts with others. Similarly, Felton & Batoces (2002) demonstrated that effective, high efficacy problem solver adolescents use more problem-solving coping strategies, have a stronger internal locus of control, have more confidence in their decision making ability, and are less likely to be impulsive unlike ineffective, low-efficacy problem solvers.As a mark of resilience, students also indicated that they are not often discouraged when they do not easily find a solution to problems standing on their way. This is in line with Masten, Best & Garmezy (1990) and Lewis (1999) who suggested that adolescents who display resilience demonstrate the capacity for solving problems and believing in their own capacities. Again, McWhirter, Hackett & Bandalos (1998) concurred with this but emphasized the resilient adolescent’s ability to consider the consequences of his/her actions and decisions. Closely linked to this was the finding that resilient adolescents do not feel shy asking questions in class when they do not understand. In order, Kauffman (1999) had earlier found that social skills in resilient adolescents offer them necessary skills to overcome shyness, communicate effectively and avoid misunderstandings, initiate and carry out conversations, handle social requests, utilize both verbal and nonverbal assertiveness skills to make or refuse requests, and recognize that they have choices when faced with tough situations.

4.4. Self-Esteem and Self-Development

- Findings on self-esteem indicated a strong explanatory power over the self-development of adolescents This implies that the more adolescents were disposed of high self-esteem, the better their self-development became; and that the extent of confidence, respect or worth that adolescents put on themselves contributes to their self-development efforts as well. These findings reflect Kassin (1998) who argued that individuals with high self-esteem exhibit characteristics such as expecting successfulness, being happy, making more effort and ignoring the unnecessary things in life. And, Yelsma & Yelsma (1998) added that individuals with high self-esteem prefer much more difficult activities; they seem to be quite sure of their efforts resulting in success; are less sensitive against emotional turbulences; are less affected by depression and depressive symptoms; are more open to accept critical analyses from efficient people; and do not experience negative effects when they notice that others are superior to them.Specific findings also showed that high self-esteem adolescents believed they will become great people in life, did not see themselves as failures, never felt insulted when their teacher rejects their ideas in class and were not afraid of being rejected by friends. These were in line with Coleman & Hendry (1990) who stated that those possessing high self-esteem show happiness toward situations, are healthy, productive and successful; make much longer effort to overcome the difficulties, sleep better at nights, have less risk in developing illness, show less tendency against accepting others and the pressures of their peers. Whereas, those with low self-esteem tend to be worried, pessimistic, with negative thoughts about the future and a tendency of unsuccessfulness.

4.5. Conclusions

- To conclude, this study investigated into resilience effects on adolescent self-development with focus on optimism, goal-directed behaviour, problem-solving skills and self-esteem. It further found that these resilient behaviours predict the self-development potential of adolescents in schools in Buea, Cameroon. It became clear that adolescents who possess these personal attributes of optimism, goal-oriented behaviour, problem-solving skills and self-esteem which serve as a buffer against adversity would demonstrate a greater propensity to be resilient and would be more positively engaged towards self-development than those without resilience. True to say, a litany of research has maintained that resilient individuals should be able to cope with disruptive, stressful or challenging life circumstances in ways that provide them with additional protective and coping skills (Richardson, 1999); and that they should incarnate the innate and in-built capacity to bounce back, withstand hardship and repair themselves. In doing so, among other things, they must demonstrate optimistic, goal-directed, problem-solving and high self-esteem behaviours (e.g. Snyder, 2000; Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006; Felton & Bartoces, 2002; Adams, 2010). In this connection, Stotland (1969) in his theory of optimism maintained that individuals with higher levels of optimism would exhibit a higher probability of reaching their goal.Meanwhile goal-oriented adolescents are more likely to anticipate events or circumstances such as school completion, work, marriage, parenting and even estimate the ages or time periods at which they will likely experience them (Crockett & Bingham, 2000). By being goal-oriented therefore, they would be able to, against all odds, pursue their dreams and march towards their futures irrespective of adversities and challenges that come their way. And again adolescents with good problem-solving skills or effective coping skills believe in their capacities, use more problem-focused coping strategies, have a stronger internal locus of control, have more confidence in their decision making ability, are less likely to be impulsive than effective and are able to consider the consequences of their decisions (Felton & Bartoces, 2002). Finally, the study found self-esteem as a dependable construct of resilience that would shape self-development efforts. In this regard, Rosenberg (1985) had argued that being satisfied with oneself, believing in one’s worthiness and incarnating self-value, self-confidence and self-acceptance are important hallmarks of self-development. Based on all these, it becomes incumbent on individuals, especially adolescents in schools to benefit from both internal and external structures capable of cultivating resilience and resilient behaviours such as optimism, goal-oriented behaviour, problem-solving skills and self-esteem to develop self-development potentials that can help them navigate and negotiate the adverse and overwhelming difficult and challenging life trajectories.

4.6. Limitations of the Study

- Our study came with a number of shortcomings. Firstly, the school sample of only 03 schools and the small sample size of only 357 appeared quite limited in providing a more general picture of young people’s exploit of resilience for self-development in Cameroon in general and Buea in particular. A larger sample would have permitted more complex statistical analyses to to establish more complex statistical relationships. Again, with only questionnaires for adolescent students to express their opinion, the risk of having collected biased opinions was high. Multiple instruments for data collection, including, perhaps interviews and focus group discussions may have provided supplementary data to render questionnaire data more dependable.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML