-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2019; 9(5): 128-134

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20190905.02

Students' Perceptions of Teacher Support and Academic Motivation as Predictors of Academic Engagement

Elizabeth Nduku Mutisya, Jotham N. Dinga, Theresia K. Kinai

Department of Educational Psychology, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Elizabeth Nduku Mutisya, Department of Educational Psychology, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Poor performance among secondary school students in national examinations has been a major concern to education stakeholders. Previous research has linked poor performance to student, teacher, home and school factors, giving little attention to the social context within which learning occurs. The purpose of this study was to determine whether students’ perceptions of teacher support and academic motivation predicts academic engagement among secondary school students in Machakos County, Kenya. The study adopted a predictive correlational research design. The target population was all year 2019 form three students. Purposive, stratified and simple random sampling were used to select 10 public secondary schools and 580 students (294 boys; 286 girls) in Machakos sub-county. Data was collected using self-report questionnaires. Descriptive statistics summarized the data while inferential statistics consisting of Pearson’s Product Moment Correlation Coefficient, multiple regression and ANOVA were used to test the research hypotheses at p < .05 level of significance. Findings revealed that both students’ perceptions of teacher support and academic motivation had significant and positive relationships with academic engagement. Academic motivation was found to be the best significant predictor of academic engagement than students’ perceptions of teacher support. The study recommended that teachers should create positive relationships with students to support their psychological needs and enhance their academic engagement and achievement. Schools should enforce learner centered learning approaches to nurture students’ autonomy and competence and improve academic achievement.

Keywords: Academic Engagement, Autonomy, Competence, Motivation, Relatedness, Teacher Support

Cite this paper: Elizabeth Nduku Mutisya, Jotham N. Dinga, Theresia K. Kinai, Students' Perceptions of Teacher Support and Academic Motivation as Predictors of Academic Engagement, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 9 No. 5, 2019, pp. 128-134. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20190905.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Students’ engagement in school is of major concern to educators and it is a vital factor in understanding academic success (Ndege & Kimengi, 2010). According to Wang and Eccles (2013), students’ active engagement in learning helps them to acquire knowledge and skills required for further education and entry into careers. It further acts as a control against school dropout and involvement in misbehavior (Skinner, Furrer, Marchand, & Kindermann, 2008). The concept of academic engagement suggests that students who actively participate in their learning perform better than those who are less engaged, therefore it is linked to academic achievement (Skinner, Kindermann, & Furrer, 2009). According to Skinner et al. (2009) academic engagement has three dimensions: behavioural engagement which involves observable actions and practices that students demonstrate in the learning process such as attending class, completing homework, effort and participation in learning activities; emotional engagement represents students’ feelings of identification and belonging to the school, and the level of interest and enjoyment they experience in learning while cognitive engagement entails students’ psychological awareness of the effort spent in learning activities, attention, concentration and persistence. Engaged students show interest and persistence in learning activities which are qualities associated with high academic achievement (Kindermann (2007). However, not all students are active participants in learning activities, some lack effort and determination to learn hence are termed as disengaged (Guvenc, 2015). Academically disengaged students may be physically present in the classroom but do not pay attention or participate in learning activities leading to poor performance. They feel bored, anxious, and frustrated because they disconnect from learning activities resulting to poor performance. Students’ academic engagement has considerable input to academic success. In the United States of America, Taylor and Parsons (2011) reported that students’ engagement can be understood as a strategic process for learning to increase academic achievement and positive behavior in school. Their assertions were supported by Wang and Eccles (2013) in the opinion that school engagement is a determinant of success in academic activities and that the latter is a key consideration for admission in institutions of higher learning and career progression. Linking academic engagement to academic achievement provides a new angle to understand students’ academic achievement. This is because lack of academic engagement among students is a major problem in schools whose obvious consequence is poor academic achievement. Akpan and Umobong (2013) reported academic engagement as a significant factor in predicting academic achievement among students in Nigeria. They also noted that it was linked to academic motivation indicating that highly motivated students were more engaged than those with low motivation. In addition, research findings in Ghana by Chowa, Masa, Ramos, and Ansong (2013) support that the extent to which students are committed to school has positive impact on academic performance. In South Africa, Wawrzynski, Heck and Remley (2012) reported that academic engagement was a predictor of positive student outcomes for both curricular and co-curricular activities. Their findings were confirmed by Schreiber and Yu (2016) in their opinion that academic engagement was a reliable predictor of good performance among university students in South Africa. In Kenya, performance in end of course examinations, particularly the Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) is highly valued. Performance in this exam is considered a door opener into opportunities for further training and career choice. Thus, students who perform well by attaining a mean grade of C+ (plus) and above are able to join university to pursue degree courses of their choice. However, not all candidates who sit for KCSE attain the coveted university entry grade. Reports from the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MoEST) show that over 50% of candidates scored less than grade C+ over the years from 2016 to 2018 (Wanzala, 2018). During the same period, a similar pattern of poor performance was observed in Machakos County where this study was done. Reports from the Directorate of Education, Machakos County shows that less than 15% of total candidates in each year (2016-2018) attained mean grade C+ and above. This trend of poor performance can be linked to unproductive students’ academic engagement. Wentzel and Wigfield (2009) argued that research on students’ motivation, learning, engagement, and achievement should focus more on the complex interactions of individuals and contextual factors. This is because learning occurs in a social context where students interact with other people such as peers, teachers and parents who impart knowledge, skills, and values to them. Since students spend a lot of their time in school, Reeves (2015) opines that teachers have a greater responsibility on how students behave, feel, and learn. Therefore, positive outcomes can be achieved by creating supportive environments that are caring, warm and friendly. Teacher support is a valuable component in the learning environment. Ryan and Deci (2000) opined that the teacher is the main actor in providing a supportive learning environment. Their opinion was confirmed by Jun-Lichen (2005) in the report that teacher support contributes more directly and indirectly to students’ achievement and engagement compared to support from parents and peers. In the United States of America, Wang and Eccles (2013) reported that students were more academically engaged in learning environments that were supportive of their needs. The basic needs sub-theory of the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) by Ryan and Deci (2000) proposes that for optimum functioning students have psychological needs that require teacher support. These are the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Students’ autonomy is the desire to take initiative and make decisions independently without pressure or control from teachers. The need for competence involves students’ understanding of their school work and the feeling that their goals are achieved. Relatedness involves close interpersonal relationships within the school that make students experience a sense of belonging, support, and safety. The extent to which teachers interact with students to support these needs can lead to need satisfaction or frustration. Students who perceive that their psychological needs are adequately supported by teachers are likely to be more committed in learning and perform better than students who experience low teacher support. In the United States, Berman-Young (2014) reported that positive teacher-student relationship led to the fulfilment of the needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness and was positively related to academic outcomes. King (2015) found that students’ sense of relatedness predicted their levels of academic engagement which also affected their academic performance. Students who experienced care and sense of belonging in the learning environment had high academic engagement, while those who perceive teachers as hostile and unfriendly express disaffection towards learning. In Korea Jang, Kim and Reeves (2016) reported that students who learned in autonomy supportive environments had higher psychological needs satisfaction and were more engaged. On the contrary, students whose autonomy was suppressed experienced disconnection with the learning experiences hence became disengaged.In Nigeria, Okunbanjo (2013) reported that students who experienced teacher support of their psychological needs were more academically engaged and had higher academic achievement. The study further found that competence, which is enhanced by positive feedback from teachers, was a better predictor of academic engagement followed by autonomy support. Ndege and Kimengi (2010) found that students’ interaction with the faculty, and a supportive campus environment significantly influenced their academic engagement and retention to completion of course at the university level in Kenya. Korir and Kipkemboi (2014) affirmed the earlier finding in their report that a friendly school climate nurtured good interpersonal relations between students and teachers. Student’s academic motivation is a factor that has been directly associated with academic engagement. Motivation refers to the forces that energize and direct behaviour (Reeves, 2012). Highly motivated students are more academically engaged than those with low motivation. They demonstrate increased participation, perseverance and commitment in learning activities. From a self-determination viewpoint as proposed by Ryan and Deci (2000), the type of motivation students adopt is related to the goals they set to pursue in learning activities. Therefore, students can pursue intrinsic or extrinsic goals. The type of goal a student chooses affects their motivation and engagement in different ways. Intrinsic goals utilize the inner resources of motivation while extrinsic goals rely on external sources of motivation. Students who pursue intrinsic goals tend to be highly motivated since they put effort, persist in learning activities, and perform better. Students who pursue extrinsic goals such as popularity and earning rewards are likely to put little effort and easily give up when they perceive learning tasks to be challenging. This is further associated with low academic engagement and achievement. Students’ academic motivation can also be influenced by expectations and value attached to learning activities (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). Students with high expectation for success and who value the learning activity tend to persist longer and perform better. However, fear of failure is associated with low expectation for success and low value for the learning activity hence poor performance. Therefore, students’ level of motivation depends on the expectation they have that they will succeed and how much they value the activity and its outcome. Students place high value to activities that are important to them and those that they find interesting (Ormrod, 2008). Activities that are useful to achieve a particular goal are highly valued. For example, a student who aspires to join the university after high school works hard to attain good grades that are required for university entry. The chances of success in a task are further determined by the students’ perceived level of competence and the level of support they receive from others especially teachers (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). Therefore, high task-value and high expectation for success are related to high academic engagement and subsequently good performance while low task-value and low expectation for success would result to low academic engagement and achievement. Saeed and Zyngier (2012) found that intrinsic motivation predicted academic engagement better than extrinsic motivation among primary school pupils in Australia. Using an older sample drawn from a university setting in Turkey, Hakan and Münire (2014) agree that students’ academic motivation predicted both the quality of academic engagement and learning outcomes. Regarding task-value, Dietrich, Dicke, Kracke and Noack (2015) reported that students’ who have high intrinsic value for learning activities were more likely to be motivated and academically engaged. Further, in a more recent study Tas, Subasi and Yerdelen (2018) reported that task-value significantly predicted academic engagement.In Nigeria Akpan and Umobong (2013) established that the influence of motivation on academic engagement was directional. Students with high motivation were likely to be more engaged than those with low motivation. Further, Babatunde and Olanrewanju (2014) found a reciprocal relationship between academic motivation and academic engagement. This implies that the extent to which students are motivated influence their level of academic engagement, likewise academically engaged students tend to be more motivated.In Kenya, Muola (2010) reported that achievement motivation among pupils influence their academic achievement. This earlier finding was echoed by Mutweleli (2014) in the report that academic motivation predicted academic achievement. In addition, the latter study revealed that intrinsic motivation was a better predictor of academic achievement compared to extrinsic motivation. The background information and literature reviewed shows that there is a link between teacher support of students’ psychological needs and academic engagement. However, majority of these studies have been done in western countries with diverse social, economic and cultural backgrounds that limit generalization of the findings in the Kenyan context. Similarly, though there is empirical evidence showing that academic motivation is linked to academic engagement, there was need for continued research in this area. This is because different studies focused on different aspects of motivation with majority emphasizing on intrinsic and extrinsic dimensions, giving little attention to the aspects expectancy and value. Therefore, the present study sought to find out whether students perceptions of teacher support and academic motivation predict academic engagement among secondary school students in Machakos County, Kenya.

2. Research Methodology

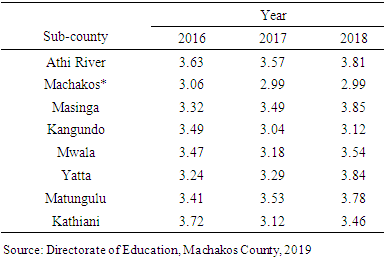

- Predictive correlation research design was adopted in this study. According to Creswell (2012) this design aims at describing relationship among two or more measured variables and advance into making predictions if the variables are found to be correlated. It is also an appropriate research design in a situation where it is impossible or unethical to manipulate the study variables. The study was carried out in selected public secondary schools in Machakos County. The location of the study was chosen due to poor performance in Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education. In the past three years 2016 – 2018, less than 15% of candidates in each year attained mean grade C+ and above. The target population was all form three students in public secondary schools in Machakos County in the year 2019. Purposive sampling was used to select Machakos sub-county from 8 sub-counties in Machakos County. The sub-county had recorded the lowest mean grade in KCSE for three consecutive years (2016-2018) in comparison to other sub-counties.

|

3. Findings

3.1. Return Rate

- The return rate for the questionnaires was 96.7%. Twenty questionnaires were discarded due to incomplete or double selection of responses. Data analyzed was obtained from 580 questionnaires.

3.2. Hypothesis Testing

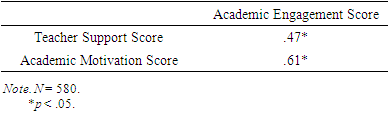

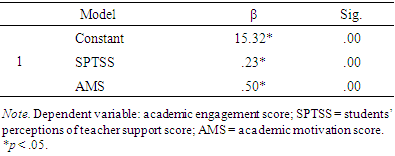

- The null hypothesis for the study stated that students’ perceptions of teacher support and academic motivation do not significantly predict academic engagement. First, a test for relationships using Pearson’s Product Moment Correlation Coefficient was done to establish the relationship between students’ perceptions of teacher support and academic engagement and between academic motivation and academic engagement. The results are presented in Table 2.

|

|

|

4. Discussions

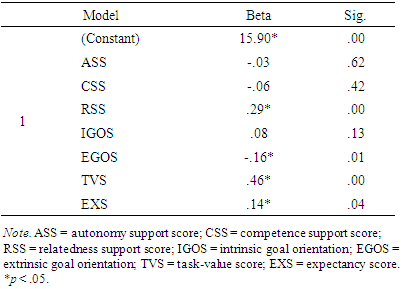

- The study objective sought to find out whether students’ perceptions of teacher support and academic motivation interact to predict academic engagement. Results show that both variables are significant predictors of academic engagement. However, academic motivation was the best predictor compared to students’ perceptions of teacher support. In the combined model, the domains of task-value, expectancy and relatedness support were found to positively predict academic engagement. The results of the study are consistent with earlier research findings by Reeves (2012); Wentzel and Wigfield (2009) who emphasizes the role of the social context in explaining academic motivation and engagement. They observed that the classroom is a social setting where students interact with teachers and peers to create interpersonal relationships. This implies that the teacher is very instrumental in organizing and structuring the learning environment to enable students achieve their academic goals. The researchers posited that students’ academic engagement is a joint product of students’ motivation and teacher support of the needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness. Guvenc (2015) asserted that academic engagement is a product of motivation and the quality of teacher-student relationship determines the amount of support provided. Positive interpersonal relations between teachers and students interact with students’ motivation to bring about academic engagement. Similarly, Gnambs and Hanfstingl (2016) reported that satisfaction of students’ psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness and competence was important in maintaining students’ intrinsic motivation. When these needs are dissatisfied, there is decline in motivation which them negatively affect academic engagement. Task-value was found to be the best predictor of academic engagement in the combined model. In addition, expectancy for success was also found to predict academic engagement. These results are in agreement with the propositions of the expectancy-value theory (Wigfield & Eccles 2000). Students attach high value to activities in which they have high expectancy for success and which they think meets their learning goals, interests and values, and they devalue activities in which they perceive failure. The results are also consistent with findings by Wang and Eccles (2013) in their report that the extent to which teachers offer support to students predicts the value placed on learning activities. Students who perceive teachers as caring, warm, friendly and approachable have a sense of belonging and are more likely to attach greater value towards learning in school. Similarly, students who feel that teachers communicate clear expectations during instructions are more likely to attach high value to the activities and have high expectations for doing well in the same activities. This is because high task-value and expectations for success influence choice of learning activities, interest and consequently increase academic engagement.Extrinsic goal orientation was found to have negative but significant prediction on academic engagement. In the goal contents sub-theory of SDT, Ryan and Deci (2000) posited that students may be engaged in pursuit of extrinsic goals such as enhanced status, increased popularity or to earn rewards. This view was echoed by Saeed and Zyngier (2012) in their finding that some elementary students were extrinsically motivated. The students worked hard to get good grades but also expected rewards as compensation for the effort and achievement. Such students also demonstrated a kind of ritualistic engagement which fluctuates depending on whether rewards are expected or not. Also, the value attached to good grades and rewards that may follow, nurture extrinsic motivation leading to academic success (Oluoch, Aloka, & Odongo, 2018). Therefore, extrinsic motivation may then overlap and overshadow the expression of intrinsic motivation making it difficult to identify the extent to which students operate on their own volition without coercion from teachers and parents.

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

- From the findings it can be concluded that students’ perceptions of teacher support and academic motivation interact to predict academic engagement. This implies that academic motivation is nurtured in a supportive learning environment which then leads to academic engagement. In addition, students who value learning activities have high expectations for success hence they are more engaged unlike students who do not value academic activities. Based on the findings, the study made the following recommendations; 1. Teachers should encourage learners to develop and exercise intrinsic motivation so as to nurture their self-determination and enhance their academic engagement and consequently academic achievement.2. Students should be encouraged to place high value on learning activities so as to increase their levels of academic engagement and improve academic achievement.3. Teachers should focus on creating positive and supportive relationships with students to enhance their competence, autonomy and sense of belonging in order to promote academic engagement.4. Teachers should provide appropriate guidance and clear information about expected behavior and clear consequences for inappropriate behavior. This enables students to make decisions and be in control of their own learning.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML