-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2019; 9(2): 52-61

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20190902.02

Does Alcohol Culture Affect Risk Propensity and Performance Impairment of Workers?

Fomba Emmanuel Mbebeb

Department of Counseling Psychology, FED, The University of Bamenda, Cameroon

Correspondence to: Fomba Emmanuel Mbebeb, Department of Counseling Psychology, FED, The University of Bamenda, Cameroon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Despite the benefit of social alcohol, workplace alcoholism appears hazardous, and poses a great threat to performance and productivity. Although alcoholism has been perceived as a function of psychological factors, the paper submits that socialization through socio-cultural values is capable of explaining alcohol-related behaviors at work. Precisely, the paper argues that alcohol culture can exert strong pressure on risk cognition and performance dispositions of workers. The present study examined alcohol culture in socio-occupational contexts and relationships with risk propensity and performance impairment of workers. The investigation used data from a survey with a sample of 299 employees (161 males, 137 females) in Western Region, Cameroon. An instrument (aggregate α=.77) was used to collect data and correlation and regression analysis performed. Following the results, societal alcohol culture was reported as a significant factor in risk propensity (β=.187, R2=.035, p=001) and performance impairment (β=.150, R2=.022; p=009). Against expectations, workplace drinking patterns failed to predict risk propensity (β=.106, R2=.01, P=.067) and performance impairment (β=.049, R2=.002, P=.395). Although workplace alcohol culture failed to determine work-related behaviours, workplace control norms should be reinforced, while deconstruction alcohol-promoting values should be given the necessary attention. Discussion has been concentrated on the role of socialization in alcohol use disorders, consequences on performance-related behaviours and implications for behavioral intervention.

Keywords: Alcohol culture, Risk propensity, Health and safety, Performance impairment

Cite this paper: Fomba Emmanuel Mbebeb, Does Alcohol Culture Affect Risk Propensity and Performance Impairment of Workers?, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 9 No. 2, 2019, pp. 52-61. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20190902.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The growing recognition of alcoholism as a social action, and a work-related lifestyle has identified occupational alcoholism as a disturbing phenomenon in health and safety management strategies. Despite the prevalence of alcohol-use disorders, it should be noted that alcohol plays useful functions in society at all levels and structures. People drink alcohol for hedonistic motives such as pleasure, pain avoidance and reduction, comfort, anxiety and fatigue management (Myadze and Rwomire, 2014; Pidd et al., 2006). Despite the importance of alcohol, drinking is often perceived as regressive strategies in sustainable ventures due to deviation from acceptable drinking style. Although the socio-cultural benefits of alcohol cannot be overemphasized, it is also considered a chronic disease having different manifestations with extended consequences on individuals, families and communities (Sudhinaraset & Wigglesworth, 2016). Moreover, alcohol abuse is associated with a wide variety of costs such as accidents, psychosomatic diseases and economic exactions, which in turn affect performance and productivity in organisations. Since alcoholism is considered a social problem in society, the growing recognition of alcohol abuse as an occupational challenge cannot be undermined. Based on evidence that unhealthy drinking habits have been closely associated with high social cost, alcoholism has been perceived as a high risk factor, fueling debates and analysis in human resource management and occupational health psychology. In this respect, Knot (2012) was categorical that workplace alcohol abuse need not be accepted as an inevitable cost of doing business. Despite the costs of drinking, the practice of planned, fast-paced, heavy drinking among colleagues and business partners is common and binge drinking is often the outcome (Fomba et al., 2012; White et al., 2018). Consequently, workplace alcoholism has been perceived as safety and performance risks with implications on health and safety management in organisations. Due to ensuing impairments, alcohol abuse produces a host of acute consequences, including injuries and deaths from falls, burns, car crashes, and alcohol overdoses (White et al., 2018). It has been noted that individuals who engage in high-level consumption patterns represent the highest level of risk to health, safety, and compromise workplace productivity (Pidd et al., 2006), and this draws in the construct of functional impairment. More recently, functional impairment has become apparent, and closely associated with significant increases in the odds for mortality, criminality, substance use and accidents (Weiss et al., 2018). Although it has often been examined as an independent variable, performance impairment has been positioned in the current context as an outcome measure of alcohol culture. The present study has largely been driven by concerns regarding, health, safety and performance of employees. This is drawn from the presumption that the socio-cultural environment could be responsible for alcohol consumption patterns and work behaviors of employees. There are evidences that workplace alcohol puts workers at risk of injury and performance, and represents a great danger to the sustainability of organizations. Although individuals generally drink to satisfy physiological needs, culture normally sanctions choice behaviours and drinking patterns (Fomba at al., 2012; Pidd et al., 2006). This no doubt projects the role of context, and particularly the role of socialization in alcohol use. This implies that drinking alcohol is a learned behaviour acquired through the process of socialization where workers acquire attitudes, values and skills necessary to be valued as effective members of the organisation (Pidd et al., 2006). This justifies a proposed model of socialization deployed in the study as capable of explaining the performance effects of drinking in socio-occupational contexts. When alcohol abuse interferes with workers’ ability to play safe and perform their duties, it becomes a legitimate concern for the employer, and this legitimizes the interest of human resource management in the alcohol challenge. In this vein, workplace alcohol programs could be beneficial to organisations in terms of productivity, reduced costs, greater employee retention, morale and job satisfaction (Knott, 2012). Despite the costs associated with alcoholism, the consumption of alcohol per se does not necessarily constitute a problem since social or moderate drinkers do not find alcohol use as problematic (Myadze and Rwomire, 2014). Problems occur only when drinking style deviates from expected code of conduct, and this is capable of distorting risk perception and impairing performance. Although it is essential to define both generic and specific domains of functional impairment (Weiss et al., 2018), the current discussion concentrates on performance impairment at work as a dependent variable. The study isolates heavy drinkers or alcoholics, whose adaptive mechanisms at work are often overwhelmed by alcohol effects for analysis. It maintains that workplace alcohol policies can provide a framework for managing alcohol related matters, and this is possible with the policies and practices of responsible, supportive and caring organizations. Today, many work settings are affected by alcohol abuse, expressing the values of a free alcohol workforce. Therefore, the present paper examines the flow of alcohol at work with regard to risk propensity and performance impairment of employees.

1.1. Socio-occupational Alcohol Lifestyle

- The setting of this study is Cameroon, a nation with a stimulating drinking environment. This is a country in which alcohol consumption has been strongly embedded in its social, cultural, political and economic fabrics as a way of life. Socio-legal requirements that determine who should drink, in what contexts drinking should occur, and how much should be consumed vary from context to context (Pidd et al., 2006). This is typical of different drinking styles employed in different milieus during different ceremonies and rituals. Moreover, wide variations exist in the cultural patterns of alcohol use, its integration into everyday life, associated meanings and how alcohol use is shaped, including physical and social consequences (Myadze and Rwomire, 2014). In the present context, alcohol plays a considerable role in how people socialize and consume alcohol during meals, religious ceremonies, weddings and on special occasions. Unfortunately, such drinking practices are perceived as customary, and usually disregard reflections on possible negative consequences. Many Cameroonians believe that drinking can help individuals to relax, deal with pressure, feel more in control of situations and deal with pressure at work (Fomba et al., 2012). In this regard, professional identities are often acknowledged through stronger family, friends and cultural values, and this is often driven by alcohol rituals. In traditional work settings, taking homemade brews has been perceived as a means of coping with the physical and psychological stress resulting from hard manual labor (Myadze and Rwomire, 2014). Today, this has logically encroached on contemporary work settings as a strategy to balance work and life. Despite the fact that the production and consumption of alcohol has not been well documented in Cameroon, some patchy information has been recorded. In 2004, the World Health Organisation (WHO) lamented that “what is problematic in Cameroon is the high cost of purchasing even one beer a week given the income of an average rural family. When comparing the price of two major beers sold in a rural village in 1983 as a percentage of male and female wages, it was found that the cost of one beer represented 60–84% of women’s and 36–50% of men’s daily wages. Drinking in these small amount means that one day’s wages is quickly consumed. The danger is when individuals start forsaking paying children’s school fees because their money is spent on beer”. This is the lifestyle of a people, who have internalized alcohol into their collective psyche, and are ready to let go all other things for a bottle of beer. Unfortunately, this drinking culture persists despite worsening situation of livelihood since then. Furthermore, these are indicators of cultural enslavement at risk of meaningful and sustainable living which is often invisible as public perception is distorted by the psychosocial and cultural functions of alcohol (Fomba et al., 2012). In another survey, The World Health Organisation [WHO] (2004), reported that large percentages of respondents in Cameroon (84%) as compared to Mozambique (77.2%) and Cote d’Ivoire (71%) had drunk alcohol in the previous 12 months. In the study, it is not surprising that Cameroon scored highest in per capita consumption among its peers. Apart from societal drinking, this is evident considering that with off-office alcohol use, drinking spots are littered around workplaces, and some transformed into “offices” by some workers and clients. Due to growing consequences on work behaviour and performance, organizations can reduce the risk of alcohol misuse by employees through legislation and health-promotion programs. In this respect, workplace rules, values, and norms concerning alcohol use may determine subsequent consumption patterns of new entrants (Pidd et al., 2006), and this is customarily done through socialization with colleagues. Despite available measures of social control, Government’s intention has been visible according to the provisions of Law No. 92/007 of 14th august 1992 on the Cameroon Labour Code. Section 97 (1) states that “It shall be forbidden to bring alcoholic beverages to the work place and to consume them within the establishment during working hours”. Article 2 further submits that “consumption of such beverages within the premises may be authorized only during normal break periods and exclusively within canteens and refectories placed at the disposal of workers by the employers. According to Article 3, “the employer shall supply water and non-alcoholic beverages shall be controlled occasionally by the Labour Inspector or the occupational health doctors”. Unfortunately, these provisions are merely cosmetic because drinking behaviours have been overridden by psychological and socio-cultural factors. In Cameroon, the Ministry of Transport is the lone Ministerial Department that has taken the challenge to control alcohol abuse at work. This is visible with alcohol test for drivers, which is designed to reduce risk and injury, though it is restricted only to some major highways. Infact, Government’s weak control mechanisms have been decried particularly over the production, distribution and consumption of alcohol. With work related alcoholism, off-office drinking is very common as workers usually escape the fragile instruments to enjoy themselves during work. It appears the presence of alcohol is perceived in all dimensions of national life and a bottle of beer is capable of facilitating business in all sectors (Fomba et al., 2012). Thus alcoholism has become a core value of the people, and its prevalence at work is more or less a societal spin-off. Despite the fact that all workplaces are vulnerable, some are more exposed, and the role of socialization in each context has been highly acknowledged. The present alcohol situation in Cameroon is anxiety-provoking, and since motives of work-related alcoholism can take different explanations, understanding the social and cultural orientation is very essential. Although individual beliefs, attitudes, and intra-psychic factors are determinants of workers’ alcohol patterns, alcohol-related culture of the organisation predominantly shapes drinking behaviour (Pidd et al., 2006). Moreover, social pressure by peers to drink heavily and tolerance of heavy drinking explains high rates of alcoholism and consumption within occupations (Olkinuora, 1984). It is therefore possible that the interaction of workers in society and at work can affect drinking attitudes and consumption patterns, which in turn affects work-relevant behaviours. In this respect, individual and group drinking behaviours are explained as occurring through a social–ecological framework (Sudhinaraset & Wigglesworth, 2016), because many organisations function in harmony with existing social and cultural norms of the society. Due to perceived influence of cultural values on work behaviours, the present discussion shifts from the analysis of cognitive to environmental determinants of workplace alcoholism. It builds on the premise that the acquisition and development of drinking patterns are more of a socialization process than cognitive dispositions, thereby assuming powerful connections among societal culture, organizational culture, drinking patterns and performance (Fomba et al., 2012). Furthermore, the paper advances that since work-related drinking patterns are elastic depending on prevailing community and work values, cultural factors can offer an explanatory framework for alcohol use and relationship with work behaviour. With close observation of the Cameroonian society in terms of alcohol consumption (Fomba et al., 2012; Sobngwi-Tambekou; 2016), the study maintains that alcohol culture in society and at work constitutes safety and performance risk factors. This view reiterates that societal and workplace patterns could constitute risk factors with corresponding danger to risk propensity and performance impairment, and draws in social learning theory as an explanatory framework. The model positions that the environment constitutes a powerful influence that defines, shapes, or prescribes alcohol related behaviours and expectations of others in a social group (Pidd et al., 2006). In addition, the paper upholds that relating societal and work culture to alcohol use risk is critical in occupational health and safety programmes. This is because it allows management and line managers to understand how changing lifestyle in society can affect work culture and possibly risky behaviours and performance.It is evident that certain occupations entail a greater risk of alcoholism than others, and affect work processes same. This implies that the nature of work activities attracts people predisposed to become alcoholics, and this appears feasible with many public service workers in Cameroon. Literature on community influences on alcohol use focuses primarily on environmental aspects (Sudhinaraset & Wigglesworth, 2016), and the question is whether stimulating alcohol culture can influence work behaviours. Considering that drinking spots are littered around work places and that workplace culture and alcohol use have been perceived as factors in health, safety and productivity hazard (Pidd et al., 2005), there is skepticism if socialization of workers into alcohol culture could be responsible for performance impairment. Furthermore, very little has been explored concerning alcohol patterns of employees with regard to workplace injuries and performance in Cameroon. It is strongly believed that the present investigation, while contributing to a body of knowledge and practice in the domain, will reawaken dormant instruments capable of advocating for a free alcohol workplace. In the light of the foregoing, the study is designed to explore the relationships between societal and occupational alcohol lifestyles, and their relationships with risk tendencies and performance difficulties of workers.

2. Related Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Orientation

- This section starts with the exploration of basic concepts and their uses in the conduct of the study, while the preceding section is on the theory deployed to explain socio-occupational drinking culture as a factor in risk behaviour and performance impairment. Alcoholism is widely seen as a multi-etiologic phenomenon to which genetic, biological, social, and psychological factors contribute (Olkinuora, 1984). Alcohol abuse is a maladaptive pattern of use indicated by continued use despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent social, occupational, psychological or physical problem that is caused or exacerbated by the use in situations in which it is hazardous (ILO, 1996). Workplace alcohol refers to the utilization of alcohol in ways that are medically, socially and legally non-sanctioned, and usually in terms of drug addiction, dependency and drug abuse or misuse (Myadze and Rwomire, 2014). It is largely defined and confined to drinking within the working day and the work setting, and not necessary within the working days and within work settings (Pidd et al., 2006). The concept of work-related consumption also encapsulates the effects of risky patterns, which are often undermined with traditional and narrower conceptualizations of workplace alcoholism. Debates on alcohol use cannot undermine the place of culture. Culture is a life style of a group of people implying it is the way they do their own things. In-context, alcohol culture is understood from the standpoint of social alcohol culture and workplace alcohol culture. This refers to the attitudes, beliefs, values, customs, and norms of a group of people with regards to alcohol use or misuse. Therefore, workplace alcohol implies a shift in shared norms and learning about alcohol and consumption patterns from society to work settings. In this respect, Pidd et al. (2006) described workplace culture of alcohol use as learned and shared norms used to transmit information to workers about the benefits of alcohol use, the workplace tradition of use, the expectations of use, and the tolerance or support of alcohol use. It is obvious that culture can also be closely associated with abuses since values or pressure from the social environment can either facilitate or inhibit normal drinking. It should be noted that alcohol use can become problematic when individuals consume regularly or in such quantities that they start to depend on it as an adaptive measure. Alcohol abuse has been perceived as a risk factor at work. Risk is a subjective construct and refers to the possibility of harm or loss presented by the existence of perceived threats within a particular situation (Cooper, 2003). Risk propensity has been conceptualized within the context of occupational health and safety as the probability that a person may be harmed or suffers adverse health effects if exposed to any hazard in the workplace. Health and safety risks imply unsafe working situations, conditions that can cause harm, while risk propensity is the probability that a worker will express unsafe or risky patterns. To Cooper, (2003), risk propensity is the likelihood that a person will take risks if he is predisposed towards doing so based on personality, and the extent to which the prevailing situation is seen as threating and the potential rewards for taking the risk. Therefore, alcohol consumption could be responsible for risk propensity considering obtained or perceived reward.Impairment has generally been discussed as resulting from substance use or in terms of addiction or dependence on the illegal consumption of alcohol or drugs. According to ILO (1996), impairment is any loss or abnormality of a psychological, physiological or physical function. Functional impairment can be defined as the real-life consequences of the disorder (Weiss et al., 2018), and could be a consequence of alcohol use disorders. It consists of the various long or short term situations, which may distract workers from focusing on their tasks. In the present context, performance impairment is a situation where workers have performance difficulties as a result of alcohol use disorders. Consequently, it is a dysfunction in occupational spheres of life, resulting from alcohol misuse or dependence, and it is deployed in the current study as an outcome measure.

2.2. Social Learning Model

- A host of theories have been proposed to explain the incidence and prevalence of alcohol abuse, and are considered as single or combined biochemical, psychological, social, cultural, economic and legal factors (Myadze and Rwomire, 2014). For the purpose of this paper, the Social Learning Theory (SLT) (Bandura, 1997) has been used for the analysis of alcohol culture in the light of at-risk patterns and performance dysfunction. The model proposes that people learn through modeling and environmental influences help determine how patterns of drinking behaviours are acquired in socio-occupational settings. SLT also refers to the reciprocal relationship between social characteristics of the environment, how they are perceived by individuals, and how motivated individuals are able to reproduce behaviours they see happening around them. The model challenges popular personality doctrines that behaviours are impelled by inner forces in terms of needs, drives and impulses (Bandura, 1971). Although social learning has not been widely used in occupational health and safety research, it appears useful in explaining a variety of risk and performance behaviours derived from alcohol lifestyle. Furthermore, social learning theory is also known as observational learning, which occurs when an observer's behaviour changes after viewing the behaviour of a model (Edinyang, 2016). This is customary in socio-occupational contexts and dictates on alcohol behaviours of people in different ways. SLT emphasizes the role of societal influences and submits that decision-making is influenced daily by others, and the modeling effect becomes probable in alcohol use. It is clear that in social learning systems, new patterns of alcohol could be acquired through direct experience or through observation and imitation. But it should equally be noted that during social learning people do not only perform responses since they also observe the differential consequence accompanying their various options (Bandura, 1971). This highlights the role of reinforcement as a key element of social learning, where behavioral outcomes drawn from experience, such as alcohol use or misuse are either rewarded or punished through social control mechanisms. Consequently, drinking experiences that are rewarded are reinforced and those that are disapproved by the socio-professional milieu are punished. This implies that the informative function of the theory is very critical in drinking contexts. There is also an emphasis on behavioral control through self-regulation, and this requires a person to self-observe, make judgments about the environment and self-response (Edinyang, 2016). This implies that cognitive events are selectively strengthened or disconfirmed through differential consequences of overt behaviour. With learning experience, reinforcement serves as a way of informing drinkers what they must do to have beneficial outcome or to avoid unproductive practices. Reinforcement is important considering that individuals copy patterns of drinking behaviour that are rewarded in terms of pleasure of alcohol, appreciation and recognition from peers. Recalling the challenges facing workplace alcoholism, SLT appears a relevant explanatory framework to understand the relationship between drinking culture and work behaviours.

2.3. Review of Past Studies

- Efforts have been made by researchers to explore safety risk and performance as consequences of socio-professional drinking lifestyles. Pidd et al. (2006) observed that social groups established norms and social controls on consumption patterns, and drinking also served useful functions in stress management, and in enhancing relationships between group members. Therefore, the pleasure of drinking is cautioned by social control measures that dictate drinking styles, and this serves as useful indicators for risk propensity. Knott (2012) found that drinking outside the workplace significantly affected workers’ productivity since it was responsible for absenteeism, accidents and poor job performance. Fomba et al. (2012) reported societal drinking lifestyle as a significant predictor of occupational consumption patterns. Although not directly on risk propensity, cultural values influenced workplace alcohol motivation, and the strength of such alcohol practices could possibly influence risky tendencies at work. In another study, Sobngwi-Tambekou et al. (2016) revealed that alcohol misuse and nighttime work schedule increased the likelihood of driving under the influence of alcohol due to socialization. Although the study did not explore socio-professional milieu as a factor, workers have often abused alcohol during socio-cultural activities, socialization among colleagues and during periods of inactivity with implications on work behaviour. In another study, Knott (2012) observed that problem drinking by a family member contributed to negative outcomes at work. Such effects, which are secondary in nature, are indicators that societal alcohol culture could be responsible in many ways for risk propensity in occupational settings. In terms of marketing culture, Sudhinaraset & Wigglesworth (2016) reported that media exposure influenced social drinking norms through advertising, product placements, media and entertainment. Although alcohol sales and marketing processes are regulated in the present context, people are still exposed to a variety of alcohol experiences that are incidental to consumption patterns. It is therefore very likely that societal alcohol practices could determine at-risk behaviours in organisations. Some studies have been realized on performance behaviours emanating from occupational alcohol culture or drinking styles. Olkinuora (1984) explored occupational-related factors affecting alcohol consumption and revealed that availability of alcohol at work, social pressure to drink at work, and freedom were responsible for problem drinking. Apart from social pressure, exposure to alcohol and lack of social control could be critical factors in workplace alcoholism. In another study, Silfies & DeMicco (1992) found that alcohol abusers have three to four times as many accidents on the job, and four to six times more accidents off the job, which in turn contribute to absenteeism. In addition, abusers are absent from work up to two and one-half times more often than non-abusers, and their medical costs and benefits run three times higher. Pidd et al. (2006) carried out an elaborate investigation on drinking culture and workplace alcoholism in different sectors. The first outcome was on important changes in perspective involving a shift in focus from exclusive concerns about ‘drinking at work’ to a much broader focus that addresses ‘work-related drinking’. In making the shift, emphasis was placed on the drinking culture of a given workplace with accompanying performance consequences. It was also discovered that apart from employees and co-workers, drinking by others in the workplace such as clients and visitors had important occupational health and safety implications. From all indications it is evident that work culture exerts strong influence on consumption patterns and at-risk patterns of employees. The findings of Fomba et al. (2012) confirmed workplace alcohol as a determinant of alcohol misuse while value pressure made work-related drinking a way of life, and in some cases a core cultural value in many dimensions of work life. In another investigation, Knott (2012) found that on-the-job alcohol abuse affected workers’ productivity resulting from absenteeism, accidents, poor job performance, disability and premature death. In addition, it was found that heavy alcohol use did not only contribute to a series of medical problems, but also increased the chances of unintentional injury both on and off the job. Results suggested that the effects of occupational drinking culture on work behaviours of employees are critical in performance processes. In a similar study, Myadze and Rwomire (2014) reported that excessive reliance on drinking adversely affected the drinker’s health, interpersonal relations as well as task performance. Sobngwi-Tambekou et al. (2016), assessed the prevalence and correlate of driving under the influence of alcohol, and observed that about one in 10 drivers was tested positive for driving under the influence of alcohol, while 3% were impaired during work. It was evident that alcohol misuse was a health and safety hazard with implications on performance. From the foregoing review, little investigation has been undertaken on the influence of societal and workplace drinking culture on work-related behaviours. The scarcity of literature is glaring in sub-Saharan Africa and particularly in Cameroon, where alcohol has been internalized as a way of life. Nevertheless, the present study stands to add value to existing literature, as well as stimulate more investigations on workplace alcoholism and accompanying consequences.

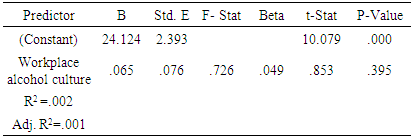

2.4. Theoretical Model of Study

- According to the model of study, alcohol drinking culture is expected to relate significantly and positively with risk propensity and performance impairment of employees at work. This has been drawn from the social learning theory, and the theoretical model of study has been presented in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Theoretical model of study |

3. Methodology

3.1. Population and Sample

- The study used an exploratory research design to examine the relationship between alcohol culture and work behaviours. Participants were surveyed in public institutions in Dschang Municipality, one of the main cities of the West Region of Cameroon. Authorizations were obtained from their respective institutions and a sample of 299 employees (161 males, 137 females), aged 25-60, recruited using simple random sampling. Participants that were available during the time or period of the investigation were used for data gathering. The instrument was distributed to participants and detailed instructions provided on the completion and return of questionnaires. Out of the 350 employees solicited to fill the questionnaires, a total of 299 employees returned valid questionnaires with a response rate of 85.42%. It was shown that majority of workers drank alcohol at meetings (37.2%), and in ordinary bars (26.5%). Workers mostly drank at ceremonies (13.6%), while drinking at work recorded the lowest frequency (0.3%). Majority of workers drank beer (80.3%), drank almost weekly (29.7%), and monthly (24.0%). Most of the employees (45.5%) consume two bottles of beer at a spree.

3.2. Data Collection Measures

- A questionnaire was used to collect information from the participants and it was divided into different subscales. The self-report scale comprised 24 items coded with five possible alternatives, “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “neutral”, “agree” and “strongly agree” with numerical values of 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 respectively. There was also a section for open items that measured demographics including age, sex, drinking frequency, drinking venue, choice of drink and quantity. To ensure reliability of the measure, a pilot-testing was conducted and necessary adjustments made. Societal alcohol culture was measured as thinking and behaviours of workers with regards to alcohol lifestyle in society, and items were adopted from the College Drinking Influences Scale (CDIS) (Fisher at al., 2007). Sample items comprised, “Drinking is a normal way of life in society” and “An occasional alcoholic drink is okay for anyone who enjoys it.” The sub scale had 5 items with a reliability coefficient of .63. Workplace alcohol culture was measured in terms of work-related behaviours in relation to alcohol intake, and items were adopted from the College Drinking Influences Scale (CDIS) (Fisher at al., 2007). Sample items comprised, “Drinking by colleagues can affect the way I drink” and “Rules about drinking at work are respected.” The sub scale had 5 items with a reliability coefficient of .72. The measure for risk propensity was intended to collect information on risk tendency of workers, and the Domain-Specific Risk-Taking (DOSPERT) Scale (Weber et al., 2002), was adopted to assess the construct. Sample items were “I take risk as a way of life” “If I do not take risk, I will achieve nothing” “I like taking risk at work.” The sub-scale had 7 items, and alpha coefficient was .85. The measure for performance impairment adopted items from the Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale –Self-Report (WFIRS-S), developed by Weiss (2005). Although the scale targets generic domains of functional impairment and any areas of impairment (Weiss et al., 2018), current interest was on performance impairment of workers. Seven items were adopted from sub-scale B, on work impairment. Sample items were “I have problems doing my work efficiently” and “I have problems working to my full potential.” The scale had 7 items and the alpha coefficient for the subscale was .89. Descriptive statistics, Person Product and simple regression were used to analyze the information. While correlational analysis explored the relationship among study variables, regression allowed the study to estimate the degree of relationship between a set of independent variable and the outcome measure.

4. Results

4.1. Relationships among Study Variables

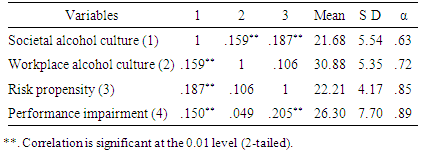

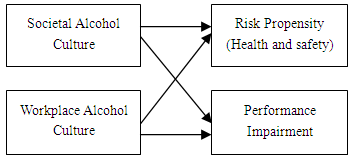

- This section presents correlational analysis and descriptive results for the study variables (See Table 1). According to Pearson correlation analysis, societal alcohol culture related significantly with workplace alcohol culture (r=.159, p< .01), risk propensity (r=.187, p< .01) and performance impairment (r=.150, p< .01). Insignificant relationships were recorded for workplace alcohol culture and risk propensity (r=.106, p> .01), and performance impairment (r=.049, p> .01). In addition, results for means, standard deviations and reliability coefficients were presented.

|

4.2. Testing Assumptions

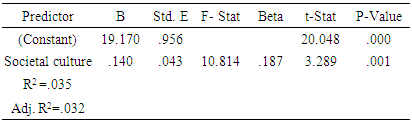

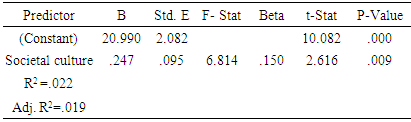

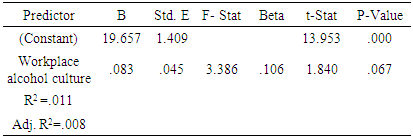

- The results of simple regression analysis determining the effect of societal alcohol culture on risk propensity have been shown in Table 2. Societal alcohol culture significantly contributed to risk propensity of workers (β=.187, R2=.035; t (298) =3.289, P=.001). The independent variable was able to explain variation in risk tendency at 03%, with F-Value of 10.814. Results further suggested that a unit increase in the level of social alcohol culture will lead to a corresponding increase in the level of risk propensity by .140 units, thereby confirming the alternative hypothesis. Accepting the hypothesis implies that an increase in the level of societal alcohol culture will influence at-risk health and safety patterns of employees.

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion

- The study investigated the role of context in drinking behaviours, and how alcohol culture relates with risk propensity and performance impairment of workers, and analysis of the linear relationship was significant. This concurs with Sudhinaraset & Wigglesworth (2016) on influence of social norms in neighborhood on binge drinking, notwithstanding individuals’ belief in binge drinking. It also agrees with prior studies on normatic group pressure (Pidd et al., 2006), societal drinking culture (Fomba et al., 2012), and socially stimulating work setting (Sobngwi-Tambekou et al., 2016). Results reflect realities on the ground as observed with qualitative reports, where workers drank heavily at socio-cultural meetings, ordinary bars and at ceremonies, but just a little at work. These are socio-cultural structures where alcohol is perceived as a core value and capable of facilitating business and pleasure among group members or sympathizers. In these venues, much alcohol is drunk by workers, and one cannot be skeptical of its role in influencing risk-taking and performance dysfunctions. Analysis also confirmed the relationship between societal drinking lifestyle and performance impairment of workers. This is consistent with the findings of Knott (2012) on family alcohol lifestyle and negative outcome at work, Fomba et al. (2012) on alcohol culture and psychological dependence, and Sudhinaraset & Wigglesworth (2016) on exposure to marketing culture and social drinking norms. Results suggest that the level of socio-cultural drinking style can disrupt effective performance of employees in the workplace. Therefore, drinking could lead to unproductive work behaviours such as absenteeism and hangovers, which affect effective performance and productivity. Perceptions therefore strongly hold that work-related alcohol effects can be very detrimental to the effectiveness and efficiency of workers in organisations.The relationship between workplace drinking culture and risk propensity did not receive any support from the study. This suggests that the way employees drink at work does not influence the expression of risky patterns that could cause harm or injury during work activities. This is inconsistent with the results of Pidd et al. (2006) on employees and co-workers on occupational health and safety implications, Olkinuora (1984) on problem drinking at work, Silfies & DeMicco (1992) on numerous accidents, and Sobngwi-Tambekou et al. (2016) on drinking culture on risks propensity of drivers. Anyway, descriptive results showed that little alcohol is consumed at work, and this may account for the fact that it does not increase health, safety and performance risks for employees. This could also be explained by the fact that workers’ occupational settings are not high risk settings and the properties of the environment appear accommodating. It should also be noted that most drinking sprees are recreational especially after work with little to do with safety hazards in occupational settings, except with cases of hangovers. The relationship between workplace alcohol culture and performance impairment also showed insignificant results suggesting that drinking style at work does not impair performance of employees. This disagrees with findings on on-the-job alcohol and absenteeism, accidents, poor job performance and productivity (Knot, 2012; Silfies & DeMicco, 1992). Although socialization is critical in drinking processes, employees are equally conscious of their occupations as a source of livelihood, and respect the necessary drinking laws and norms pertaining to alcohol use at work. Furthermore, qualitative data showed that the amount of alcohol consumed at work is just 0.3%, and this could possibly account for the insignificant results. In African traditional work settings, alcohol is integrated into work processes and social norms dictate eating and drinking at work. Participants could have internalized such values where workplace alcohol does not influence negative behavioral outcomes at work, although this could be explained by personality characteristics of individual workers.

5.1. Implications

- The study is relevant from the standpoint of workforce care, and provides feasible building blocks capable of generating appropriate policies and intervention to deter workplace related alcoholism. Analysis of occupational alcoholism as a risk factor is gaining increased attention and this warrants corporate efforts to deal squarely with alcohol problems (Fomba et al., 2012). In this respect, appropriate measures should be put in place to control alcohol in the work place, particularly at the societal level. Increasing reinforcement to reduce risk propensity and counter impaired performance is indispensable. Furthermore, it should be acknowledged that the consumption of alcohol has implications for workplace health and safety, and this is mostly derived from drinking styles in society. Adaptive life skills are abilities necessary for daily tasks and they should be able to deconstruct dysfunctional impairment, and promote well-being at work, and life satisfaction (Weiss et al., 2018). Since alcohol use impairs co-ordination, judgment and decision making in work processes, it should be redressed to ensure organizational health and productivity. Moreover, the effects of alcohol culture on health and safety risks and performance impairment have been unveiled with policy and practical implications. Alcohol and drug testing is an essential element of a drug-free workplace program (Knott, 2012), but in Cameroon the practice is renounced only with the Ministry of transport with the institution of alcohol testing programmes for drivers. Despite the nonchalance of the Government and the inertia of enterprises, it is regrettable that harmful effects of alcohol misuse are far reaching and range from accidents and injuries to disease and death with secondary effects on family, friends, and society (Sudhinaraset & Wigglesworth, 2016). This calls for the reinforcement of social control norms and education of the public, and workers in particular on the harmful effects of alcohol on individuals and occupational life. Nevertheless, the problem in Cameroon is not the absence of legislation but that of effective implementation. In most work settings, regulatory mechanisms are perceived to have failed to bailout problem drinkers due to cultural dictates of the society (Fomba et al., 2012). Efforts should focus on the social, psychological and economic exactions from alcoholics as an advocacy and behavioral change strategy. It should be noted that exposure to alcohol and environmental pressure has been accused of alcohol abuse due to non-respect of laws establishing drinking spots, and this requires responsive actions. Therefore, interventions that integrate policy, treatment and prevention strategies, and target workplace culture to influence behaviour are more likely to be effective in reducing alcohol-related harm (Pidd et al., 2006). The Government needs to exert more control and local administrators and traditional authorities should be involved in promoting a free alcohol environment. In addition, community education at meetings, ceremonies and on the media should be initiated and intensified. Although workplace alcohol was not significant with safety risk and performance, influences from the wider alcohol culture affect workplace processes in the likes of health and safety risks. Despite the fact that productivity and health care costs negatively impact on both episodic and chronic heavy drinking (Knott, 2012), attention should be given to wider alcohol influences. The socio-cultural perspective of the model implies that social control is necessary and workplace interventions should not isolate lessons from the social learning theory since societal culture appears to play a critical role in the development of workplace norms regarding alcohol use (Piddet al., 2006).There are limitations due to the fact that many organisations do not have workplace health and safety policies and alcohol policies in particular. It therefore becomes difficult to implement what is not available on policy statements, though management still plays tough on problem drinkers. In spite of the fact that some managers believe in strong disciplinary measures as a deterrent to alcohol abusers (Silfies & DeMicco, 1992), this may instead become counterproductive considering that drinking values have been highly internalized at societal level, and workers have become mentally and emotionally attached to alcohol. In terms of workplace policy strategies, initiatives to educate and train supervisors and line managers on how to handle cases of alcohol abuses are indispensable. Health professionals and counselors could play a vital role in influencing attitudes and perceptions towards drinking in order to ensure health, safety and effective performance. Most often this is the direct responsibility of the Human Resource Management Department, particularly the Safety or Occupational Health Unit. The service has preventive functions, and is responsible for advising the employer, as well as the workers and their representatives on the requirements for establishing and maintaining a safe and healthy working environment for optimal physical and mental health in relation to work (ILO, 1996). This is ideal, but the question is whether Human Resource Management Departments do exists with occupational health units, and whether they are fully aware of their role. More so, this is only possible if they are functional in their respective organisations to address workplace alcohol disorders. There are different theoretical explanations connecting environmental factors and consumption patterns, and a unifying and consistent explanation is culture (Pidd et al., 2006). SLT has been used as explanatory framework and the engine of culture is socialization and perceived as capable of dictating on alcohol drinking patterns. Although people learn through observation and imitation of behavioral patterns, the rudimentary form of learning rooted in direct experience is governed by rewarding and punishing consequences that follow each action (Bandura, 1977). This reemphasizes the role of socialization on alcohol drinking styles of workers exposed to drinking opportunities, as well as reward and punishment as control mechanisms. SLT is relevant gives explanation to environmental influences of alcohol consumption. This is because societal culture appears to play a critical role in the development of workplace norms regarding alcohol use (Pidd et al., 2006). Therefore, it is possible to use cultural properties to redress problems of norms and attitudes of heavy drinkers at work. Therefore, the application of SLT could focus on environmental modification and cognitive restructuring to improve individual’s sociability to learn new ways of coping with drinking demands or pressure from the social environment.

5.2. Conclusion

- Alcoholism no matter how it is defined is an enormous problem in work life, and heavy drinking and alcoholism as a problem calls for preventive efforts and treatment (Olkinuora, 1984). This could possibly reduce risk propensity while improving health, safety, performance and productivity in organisations. Although personality factors could be highly responsible, contextual values should be considered in any strategy that purports to solve problems of workplace alcoholism. However, studies have revealed that attention on changing social norms is insufficient, since broader interventions that influence multiple levels of an individual’s environment may have greater impact (Sudhinaraset & Wigglesworth, 2016). In this respect, education on alcohol consumption and safety practices could influence desired behaviours of employees. This builds on the recognition that a well-designed and carefully-targeted health promotion programs can cause changes in employee behavior and reduce associated risk factors (Silfies & DeMicco, 1992). Therefore, any society free of problematic drinking is a pathway to alcohol free workplace. In the process, organizations with policies and procedures designed to eradicate alcohol abuse during working hours (Knott, 2012), could be more effective in controlling work-related alcohol effects while promoting maximum functioning of the organisation. However, the findings of the study must be interpreted with caution since it is difficult to determine whether alcohol drinking culture in society and at work, and having results from a single sector could be directly generalized to safety and health promotion behaviours of employees. Despite these challenges, it is important to develop new strategies to systematically examine the impact of drinking lifestyles on alcohol abuse, and accompanying outcome on risk propensity and performance difficulties. Despite policy gaps in ensuring a free alcohol workplace, the study noticed some significant gaps and limitations in terms of data on workplace alcohol in Cameroon. Further research activities could be expanded to occupational alcoholism and differential analysis of individual and environmental factors for workers in the public and private sectors.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML