-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2019; 9(1): 29-39

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20190901.04

Delinquent Behaviour as Dissociation between Prescribed Aspirations and Socially Structured Avenues: The Case of Stronger Social Bonding and Secure Attachments

Stephen Ntim, Michael Opoku Manu

Faculty of Education, Catholic University of Ghana, Sunyani, Ghana

Correspondence to: Stephen Ntim, Faculty of Education, Catholic University of Ghana, Sunyani, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This report provides cross-cultural evidence suggesting that tightly bonded juveniles are less likely to act in delinquent behvaiour irrespective of socioeconomic status. Using multiple regression on four dependent variables matched to selected independent and control variables, the findings of this study suggest that stronger and secure attachments of social bonding mitigate the negative effects of delinquency. Thus, strong regulatory presence of the collective conscience exemplified in social bonding with social institutions hinged around strong parental and extended family attachments, religious values, etc. by far reduces misconduct and criminality. The implication from this underscores the need to ask why people do not commit crimes or engage in misconduct rather than why people commit crime. These findings also have implications for theory on delinquency, namely, the overarching mediating influence of stronger social bonding and secure attachments in minimizing the occurrence of delinquent behaviors.

Keywords: Delinquency, Stronger bonding, Secure attachments

Cite this paper: Stephen Ntim, Michael Opoku Manu, Delinquent Behaviour as Dissociation between Prescribed Aspirations and Socially Structured Avenues: The Case of Stronger Social Bonding and Secure Attachments, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 29-39. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20190901.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Juvenile delinquency is found to be heavily correlated to low socioeconomic status (Hay, Forston, Holist, Altheimer & Schaible, 2007; Loeber & Farrington, 2012). Some theoretical explanations such as the strain theory as well as social control theory offer some conceptual explanations for the link between the two variables. Other research studies continue to offer empirical evidence suggesting that socioeconomic factors are critical predicting cause of juvenile misconduct (Johson et al, 1999). Similar evidence is found in the study of Snyder and Sickmmund (2006) in which the claim is made that one of every six juveniles is likely to come from low socioeconomic background. In many studies conducted in the United States, younger people from low socioeconomic ethnic groups from African and Hispanic descent are three times more likely to live in poverty and be engaged in juvenile misconducts compared to younger people from the Caucasian race. Some researchers make the conclusion that the relationship between low socioeconomic status and risks behaviors is so significant that the risks of younger people from low socioeconomic status being arrested is so high (Cohen, 1955; Lawrence, 1998; Pagani, Boulerice, Vitaro, & Tremblay, 1999).Thus, almost all writers dealing with the subject of Juvenile delinquency make the submission that it is more accentuated in the lower socioeconomic strata (Burgess, 1952). Social class consequently is perceived to be the critical predicting variable in contemporary theories that explain delinquency. These ideas have therefore extended Merton’s (1957) sociological thesis that aberrant behavior is a sociological symptom of dissociation between culturally prescribed aspirations and socially structured avenues for making these avenues to become realized. These theories have almost exclusively focused on lower class. In short, there is ample empirical literature evidence suggesting that youth from low socioeconomic status are more likely to be involved in delinquent behavior (Bjerk, 2007; Jarjoura et al, 2002; Loeber et al, 2008). The Strain and the rational choice theories make the argument that delinquency is a direct offshoot from economic resources of families (Cornish & Clarke, 1986; Williams & Hawkins, 1986).Notwithstanding the above empirical findings, other research studies also suggest negative correlation between low socioeconomic status and delinquent behavior. For example, Defoe et al. (2013) make the thesis that there is no relationship between the two variables. Legleye at al. (2010) were of the view that both young people from lower socioeconomic status as well as those from higher socioeconomic status are equally implicated in delinquent behaviors. This link between economic deprivation and delinquency is contrasted by social disorganization theory which makes the submission that other variables such as neighborhood quality tends to mediate the correlation between deprivation and delinquent behaviours (Sampson, Raudenbusch & Earls 1997; Shaw & McKay 1972). The point of emphasis of the social disorganization theory is that it is rather neighborhoods that trigger offending behaviours due to lack of social capital and collective supervision. Families from low socioeconomic status, compared to those from high socioeconomic status are more likely to be less stable and poorer. Thus, copious research evidence shows that delinquency is perceived to be typically more acute in neighborhoods having low levels of affluence as well as low residential stability (Sampson, Raudenbusch &, Earls 1997; Thompson & Gartner (2014).Even though, neighborhood quality is implicated in delinquent behaviour, it could equally be mediated by parenting as argued by the family stress model (Conger, et al, 1992; Conger et al., 1994). The control theory makes the hypothesis that when there is a positive parent-child relationship, with much stronger social bond, delinquent behaviors are likely to be precluded (Hirschi, 1969). On the other hand, when parents themselves are stressed, parent-child relationships tend to be diminished (Conger, et al, 1992). In situations such as this, younger people tend to have a preponderance towards delinquent behaviours, if they perceive parents to have less knowledge about their activities and spend less time with them (Hoeve et al., 2009; Trentacosta et al., 2009). In sum, the link between juvenile delinquency and low socioeconomic status as it exists in the literature in some geopolitical areas could be categorized under the following four subheadings: a) class consciousness and delinquent behavior, b) alienation and delinquent behavior, c) negative labeling and delinquent behavior, d) social bonding and delinquent behavior. Each of these in isolation or in relation with the others trigger misbehaviors. For example, class consciousness, defined as awareness of social stratification by Scott (2006) could precipitate the youth of disadvantaged class to misbehave, and become antagonistic to those perceived to be the cause of class inequality (Dowers & Rock, 2007; Olsen, 2011). This notion corroborates those sociological findings that suggest that youth gang membership as a resistant phenomenon is born and nurtured from structural inequities (Librett, 2008). Consequently, class consciousness is predicted to be a possible cause for delinquent behaviors and this is not unrelated to low socioeconomic status. Alienation, defined as separation from self or from other significant others or from schooling is connected to such delinquent behaviors as violence, vandalism, alcoholism and other chemical dependency (O’Donnell et al. 2006; Safipour et al. 2010). Other findings suggest relationship between alienation and lack of prosocial behaviors as violence, truancy, etc. (Deutschmann (2007). Reijntjes et al. (2010) make the submission that younger people when they feel alienated by peers have the tendency to exhibit aggressive responses. Those likely to be alienated are those from deprived socioeconomic status. Many scholars are also of the view that delinquent behaviors become heightened when there is negative labeling by others. Link and Phelan (2001) make the claim that people who are stereotyped are de facto disapproved by others based on certain undesirable parameters. This tendency triggers delinquent behaviors from the disapproved persons. This line of thinking is not unrelated to that of Grattet (2011) that others, such as teachers, peers, parents’ etc. responses to individual’s act in social interactions can induce delinquent behaviors. What is being alluded to here is that delinquent behaviors for most of the time are shaped by individuals based on community’s reaction to these individuals. Weak social bonding and insecure attachments have also been identified as being the root cause of misbehaviour. Longshore et al (2004) for example share this view. According to these authors, it is the lack of commitment to conventional moral and belief systems as well as insufficient attention to conventional ways that precipitate misconduct. The level of parental attachment and involvement with respect to standards of conduct and behaviour have also been identified by other researchers to implicate the behavior of younger people (Pizzolato & Hicklen, 2011).

1.1. Statement of Problem

- The question repeatedly broached in psychosocial studies on aberrant behavior is whether or not theories such as the social control and the attachment theories could be extended in other geopolitical cultures. While many empirical studies have explored the usefulness of such theories in some cultures, very few studies have been conducted to test their applicability in the context of other cultures with extended social bonds. For example, in many African cultures with extended family systems, broader social bonding, and many affectional identifications within the extended family structure, low socioeconomic status per se, (which is often not infrequent), cannot often be hypothesized to constitute a strong predicting factor for delinquent behavior. Consequently, as Cernkovich and Giordano (1992) observed, the assumption could not always be made that the underlying causes or processes which trigger deviant behaviour in one geopolitical culture or among one race are equally applicable in another. Secondly, given that studies examining the nexus between low socioeconomic status and delinquency from other geopolitical areas often perceived to be economically deprived is scarce, it remains unclear whether the social control theory of stronger social bonding and many affectional identifications in the extended family structure are strong enough to mitigate possible deviant behaviour or the link between the two variables still remain invariant. Thirdly, findings from copious studies suggest that poor attachment relationships to parents is a determining factor for increasing the risk of delinquent behaviour. There are too many inconsistent findings in the literature, making it difficult to make any generalizations. Additionally, many previous studies in the African context do not appear to have systematically examined at what point in the age levels is the attachment-delinquency much greater whether in younger children or late adolescents’ adults. This present study therefore examines the relationship between low socioeconomic status and delinquent behaviour within the context of the impact of stronger social bonding, secure attachments and affectional identifications in the extended family structure.

1.2. Research Questions

- 1) How strong is the relationship between low socioeconomic status and delinquent behavior?2) In what sense does stronger social bonding in lower socioeconomic status mitigate delinquency? 3) How strong is the association between attachment and delinquency?4) Is the association between attachment and delinquency moderated by the age of the child?

1.3. Significance of Study

- The findings of this paper will be beneficial to stakeholders in Education especially classroom teachers, school administration, parents as well as the Ghana Education Service to understand some of the underlying psychological factors of students disruptive behvaiour in schools. While many studies have been conducted in other geopolitical areas linking adolescent and students’ disruptive behaviors to some racial and ethnic samples, based on the principle of economic deprivation and family background, the same cannot be assumed automatically to be applicable to other areas. Consequently, the outcome of this paper will constitute an invaluable source to Educational and School psychologists especially Counselors. Additionally, the findings will contribute to the existing literature on Juvenile delinquency.

2. Theoretical Framework/Literature Review

2.1. Delinquency in Ghana

- Since 2010, Juvenile Delinquency has been growing at an alarming rate in Ghana (Boasiako & Andoh, 2010). The 2007 Department of Social Welfare in its Annual Performance Report mentioned 276 Juvenile delinquency cases. Similarly the Ghanaian Prison Service in its 2010 Report mentioned an average daily lockups of 115 Juvenile offenders. To understand this upsurge, one of the key ways is to explore the background of these offenders. This is the way to understand better the factors triggering them into delinquent behvaiour. (Simões et al., 2008, Hunte, 2006). The seminal work on delinquency in Ghana could be traced back to Boasiako and Andoh (2010), Arthur (1997) and Weiberg (1964). These early studies were influenced by Western theories of the dissociation between culturally prescribed aspiration on one hand and socially structured avenues on the other, with heavy emphasis on cultural deprivation and low socio-economic status. These authors tried to replicate these from the Ghanaian perspectives. However, in so doing, little emphasis was placed on the influence of stronger family bonding, secure attention and affectional identifications typical with the Ghanaian extended family system. Their findings suggested strong support for the differential theory implying that the Ghanaian sociocultural milieu supported this differential theory of peer group influence. Even though, the findings provided some evidence for this theory, but as to whether or not, respondents learned delinquent behaviour from disorganized family or neighborhoods which might have precipitated this delinquent behvaiour in the first place was not explored. (cf. Gibson et al., 2010; Jang & Johnson, 2001; Shaw & McKay, 1942).

2.2. General Theory of Crime

- The General Theory of Crime was proposed by Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990). Their submission is that delinquent behaviors have a common pattern which are manifested in self-control. ‘Self-control’ as used in this theory is the extent to which an individual would be able to overcome or not overcome temptations in a given period of time. Therefore, comparing delinquent behvaiour with non-delinquent behavior, the former have low self-control. This low self-control triggers their inability to resist deviant activities. The cause for this inability is the ineffective socialization process during the early period of their life (Longshore, Chang, Hsieh & Messina, 2004). This in turn is influenced through the process of acquired behvaiour, which are learned and taught through the process of socialization (Shoemaker, 2009). In this perspective, when parents at the early stages of socializing the child into the norms of the society, fail to reprimand children for wrong doing, inadvertently, would be promoting lack of self-control. This position appears to contradict the social bond theory by Hirschi (1969; 1977) which makes the submission that during the period of adolescence, those with much stronger attachments to parents and friends have less chances of becoming delinquent, compared to those without strong attachment. Consequently by this general theory of crime, whether or not adolescents would succumb to peer pressure or not is predicted on the extent of their self-control.

2.3. Becker’s (1963) Labeling Theory of Delinquency

- Labeling theory of delinquency is often attributed to Becker’s work of 1963. This theory holds the view that society’s reaction to delinquent behaviors has some future link on the behaviour of those with delinquency. What in fact this theory tries to underscore is this: it is society which labels certain behaviors as ‘delinquent’ and others as ‘non-delinquent’. Labeling theory then seeks to examine people’s response to negative labeling during social interaction (Franzese, 2009). The implicit assumption in this theory is that negative labeling has influence on individual’s behvaiour, since individuals generally define themselves through other people’s perception of them (Conyers, 2013). Thus, once people are tagged as ‘delinquent’, society in turn begins to treat them in manners consistent to that label. These people in turn begin to adapt to these ways as part of their self-image and this affects their subsequent behaviors (Putwain & Sammons, 2002; Regoli et al., 2008; Shoemaker, 2009). This is not different from the concept of what Merton (1968) referred to in Social Psychology as ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’ which is a confirmation of those so stereotyped to put up behvaiour overtime to confirm the predicted behvaiour.

2.4. Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory of 1939

- Sutherland Differential Theory follows the same model as the Social Learning Theory which makes the thesis that people develop attitude and skills which can be delinquent due to increased contact with those who harbor norms of delinquency (Wood & Alleyne, 2010). This is especially so with adolescents. Their exposure to delinquent behaviors heightens the likelihood to imitate such behaviors. This constitutes one of the key submissions of the social learning theory of Bandura (1977). So the extent to which young people continue to be exposed to attitudes that encourage disrespect for law and order, compared to peers who are law abiding, there would be delinquent behaviors. Behaviour after all is acquired. This means we learn to acquire behaviours especially through interaction with significant others, most of who will be typically parents and peers. The propensity for a child to be delinquent is therefore contingent upon the extent of the child’s association with conventional as well as criminal associations. When a child for example grows up in a company of criminals and have more contacts which reinforce criminality, such a child is likely to become a criminal as well (Regoli et al., 2008). The implication is that because of such contacts, children perceive that the benefits of commuting crime would be more satisfying than non-committing it because such a behvaiour would be reinforcing to the significant other. Similarly, in adolescence when young people perceive that the people they share intimacy with approves of deviant behaviors, they maintain and develop such behaviors (Keijsers, Branje, Van der Valk, & Meeus, 2010; Vitaro, Brendgen, & Tremblay, 2000).

2.5. Social Control Theory of Delinquent Behaviour

- Social control theory of delinquent behaviour emphasizes conformity to norms (Clinard & Meier 2008). This theory is based on the assumption that lack of conformity to social norms is the result of a broken or weak bond to society (Downes & Rock, 2007). This assumption is supported by Good (2011) with the claim that when there is a weak bond towards basic social institutions such as the family and the school, there is the likelihood that this would lead to delinquent behvaiour. This is because individuals who lack control to conform to social norms have a tendency engage in misconduct. There are four dimensions of the social bonds: a) attachment; b) commitment; c) involvement and d) moral beliefs. Attachment has to do with the ties of affection an individual forms with significant others, especially parents (Deutschmann 2007). The presumption is that individuals are less likely to disrespect social norms, if there is a strong bond of attachment with significant others compared to those individuals who do not care about expectations from significant others because of lesser bond of attachment with significant others. This lack of expectation could contribute to delinquent behvaiour. The second dimension of commitment is based on the premise that there is a strong relationship between individual’s aspiration of engaging in conventional activities and the acquiring of conventional values. In the same way, there is a negative correlation between commitment and delinquent behaviors (Downes & Rock 2007). Involvement has to do with the frequency with which an individual engages in socially approved activities. Thus, individuals are less likely to commit crimes when there is a strong commitment to conventional and socially approved values either because they spend more time in conventional activities, such as studying and therefore have less time to commit crime (Inderbitzin et al. 2013). Beliefs are the acceptance of the moral values of society (Thio et al. 2013). The submission is that the stronger the awareness, understanding as well as agreement with social norms and rules, the less the probability of the individual engaging in delinquent behvaiour. However, this is also conditioned by whether or not the individual ignores or exaggerates the underlying beliefs towards social rules (Kubrin & Stucky 2009).

2.6. Differential Oppression Theory

- The Differential Oppression Theory holds the view that in relation to children, parents as well as other significant figures occupy a position that affords them the opportunity of maintaining order in the homes that tend to be oppressive to children. In this, authority figures are able to influence children’s choices with respect to peers, food, clothing etc. which might be oppressive to them. Children on the other hand occupy less social positon to negotiate and submit to authority. This authority includes obeying rules designed to meet adult’s convenience through such abuse as physical, emotional and sexual. This may compel children to adopt reaction leading to problem behvaiour as substance use and other forms of delinquency (Rgeoli & Hewitt, 2006). Therefore according to this theory delinquency is the result of adoptive strategy by children suppressed by their parents.

2.7. The Strain Theory of Low Socioeconomic Status

- Copious evidence suggests connection between low socioeconomic status and negative outcomes among adolescence such as increased antisocial as well as poor mental health (Devenish, Hooley, & Mellor, 2017; Piotrowska, Stride, Croft, & Rowe, 2015; Reiss, 2013). Common factors typical of low socioeconomic status can precipitate individual’s participation in delinquent behaviours. For example, financial inability to acquire needed goods can increase the risk to delinquent involvement (Agnew, Matthews, Bucher, Welcher, & Keyes, 2008). Other factors include parental stress from bringing up children in indigent situations, poor parental supervision, living in high risk neighborhood exposed to increased exposure to delinquent behvaiour (Costello, Keeler, & Angold, 2001). Recent research indicates that environmental toxins such as lead which is identified to be related to cognitive defects and criminal behvaiour are typically found in low socioeconomic neighborhoods (Boutwell et al., 2016; Hanna-Attisha, LaChance, Sadler, & Shnepp, 2016; Wright et al., 2008), compared to less disadvantaged neighborhoods. The roots of the Strain Theory can be traced back to Durkheim’s sociological perspective of anomie in his book Suicide. In this classic work, the thesis of Durkheim is that anomie suicide results when appetites are not restrained by society. One of the long-standing adaption of this is Robert Merton’s strain theory of crime in 1938. Merton theorized that deviance arose in the United States as the result of an individual’s inability to achieve the “American dream”. Specifically Merton made the submission that high crime rates in the United States were the consequence of a disconnect between an individual’s monetary goals and the available legitimate avenues to attain them. In this way, crime became an illegitimate means to the positively-valued end.

2.8. Present Study

- Many empirical studies suggest correlation between low SES and weak social institutions (collective efficacy, community organizations, and public schooling) and consequently opportunities for offending (e.g., easy access to criminal gangs, lack of supervision, and easy access to firearms) tends to be high. This notwithstanding, scarce research has been conducted to investigate the extent to which the link between low SES and delinquency remains for adolescent growing up in other geopolitical systems with a strong social bond of attachment and affection of extended family system. The literature on delinquent behvaiour as presented above underscores one recurring theme, namely, that delinquency is more a learning behaviour acquired from the environment. Humans are not naturally born to become delinquent. Rather, it is the socio-cultural environment in which one is raised up (the family, the peer group etc.), that either precipitates or minimizes the occurrence of delinquency. If this assumption is correct, the question is this: does it de facto imply that when one is born into a low socioeconomic status, one is likely to become delinquent as implied in the strain theory? What about the influence of strong parental attachments proposed in the social control theory? Within the context of such questions, this study tested the social bond theory thesis that adolescents, are not likely to become delinquent, if they have a strong bond of attachment to families. They ensure that they do not disappoint parents and other family members. Therefore the hypothesis of this study was that strong parental and family attachment would predict reduced delinquency (McCuskey & Tavor, 2003; Worthen, 2012). With this hypothesis as backdrop, this paper examined the following: a) the strength of relationship between socioeconomic and delinquent behvaiour; b) whether or not the association between lower socioeconomic status and delinquency is moderated by stronger social bonding; c) how strong if any of the association between attachment and delinquency and d) whether the association between attachment and delinquency is moderated by the age of the child.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

- A random purposive and stratified sampling size of one hundred and sixty (160) adolescents from four Senior High Schools in the city of Kumasi, located in the middle belt of Ghana took part in this study in June 2018. Using a two-phased stratified cluster sampling, namely, first selecting schools within the Kumasi city by their income status and secondly selecting schools through such criteria as: a) purely public; b) public but faith-based managed; c) Category A schools (for exceptionally brilliant students from the Junior High Schools and d) secondary-technical (for the average student). Through the use of probability proportionate to size design, the size in each type of school was calculated using average class size of forty (40). In terms of age, adolescents were between 15 and 18 years with parents also aged between 24 and 48 years, with an average age of 33.85. One hundred and twenty eight (128) of adolescents, constituting 80% reported coming from stable family with both parents staying together, 10% were from single parenting home and 10% staying with grandparents and uncles. Forty percent of participants were females, while the remaining were males. Participants were largely Ghanaians, with few Lebanese born and bred in the Kumasi city. All were normal developing adolescents with no diagnosed disability.

3.2. Measurement

- Dependent Variable(s)Using an adapted version of Elliot and Ageton (1980) measurement instruments, this study measured behaviours assumed to be delinquent through selected ten (10) items: a) being involved in gang fights; b) choosing to be unruly; loud and rowdy in public places; c) using violence against teachers; d) hitting other students; e) deliberately vandalizing trees and lawns on school compound; f) carrying knife, clubs; g) attacking someone; h) sexual harassment; i) throwing objects out of moving cars; j) fist fighting. These ten (10) items were subsumed under three broad areas of: a) Assault (Cronbach alpha =.83); b) School Delinquency (Cronbach alpha=.74) and c) Public Disturbance (Cronbach alpha-.65). Assault had four (4) items, School Delinquency three (3) items and Public Disturbance three (3) items. An aggregate Cronbach alpha was calculated collectively for all items under each of the three broad areas rather than for each of the ten items. Using a Likert’s scale, participants showed how many times they committed any of these delinquent acts within a year. Responses varied from never (1), rarely (2), sometimes (3), generally (4) to always (5). Higher scores indicated higher involvement in delinquent behaviors. A total delinquency was also created (Cronbach alpha=.86).Independent Variable(s)Independent variables were measured using a variant of Demuth and Brown (2004) to assess the following three measurements: a) Family Structure (Cronbach alpha=.82) which included the following: i) Stable family of two biological parents; ii) Other two-parent-family such as one biological parent and one adoptive parent figure; iii) single parenting family: a family having one biological parent and iv) number of extended family, namely, numbers of siblings, adult- household members as well as older generation in a family; b) parental bonding and attachment (Cronbach alpha =.83): this measured how close and bonded the respondent felt to a parent especially the mother in such areas as maternal/paternal warmness, how satisfied a respondent felt in communicating with parents and their total satisfaction in their relationship with parents. Answers varied in a Likert’s range as follows: 1=not at all to 5=very much or 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree, or from 1=strongly agree, 2=agree, 3=neither agree nor disagree, 4=disagree, 5=strongly disagree; c) Parental control (Cronbach alpha =.78): this was measured using the following seven behaviours as indicators: i) when respondents returned home on weekends; ii) what they watched on TV; iii) how long they watched TV; iv) time they went to sleep on weekdays; v) the persons they hung around with; vi) how they dressed; vii) what they liked to eat. Each question was answered by 0=no or 1=yes. The aggregate of the answers were summed in mean scores: higher mean score implied higher parental control; d) Family attachment (Cronbach alpha =.85): three items were measured on this scale as follows: i) how respondents felt their families were close to them and understood them; ii) gave them the needed attention; iii) corrected them when they erred. They answered as follows: 1=not at all, 2=very little, 3=somewhat, 4=quite a bit, or 5=very much. The higher scores meant the higher family attachment; e) Religion as social bond (Cronbach alpha =.75: Participants were asked about: i) how frequent they attended religious services and ii) how frequent they engaged in youth activities in their churches such as bible study groups or Sunday school teaching, if they engaged in these as follows: 1=once a week or more, 2=once a month or more, but less than once a week, and 3=less than once a week, or 4=never. Higher score implied higher religious engagement.Control variable(s) In conducting research of this type, the need to control extraneous variables that might inadvertently influence the reliability of the findings is very crucial due to the competing theories of delinquency. We tried to control such variables as respondents’ age, their socioeconomic status, self-control. Age was controlled because life-course theory makes the submission that age was related to delinquency. Participants ranged from 14- 18 years of age. Socio-economic status was checked if for example if respondents’ parents received any remittances. Parental education also found to explain delinquency gap between some races was checked by measuring parental educational level using higher level among two-stable parents and that of single parents.

4. Results

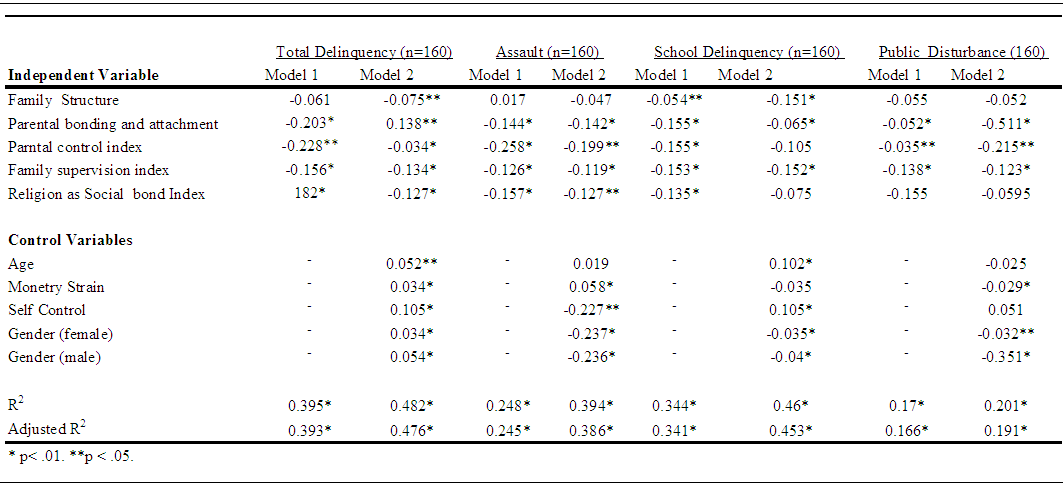

| Table 1 |

4.1. Assault

- When younger people have higher levels of parental bonding and attachment, parental control, family supervision index as well as religion as social bond, engaging in assault was not very likely as shown in the data in Model 1 in the Table. Almost all the social bonding indicators were significant. This suggests that the stronger the social bonding, the less likely younger people would be associated with engaging in behaviours seen to be delinquent. When control variables were factored into the analysis as indicated in Model 2 in the Table, the social bonding variables (with the exception of family structure index) still remained statistically significant even though most of their beta coefficients were reduced in size. For example, family bonding and attachment was reduced from -0.144 to -0.142, parental control index from -0.258 to -0.199, family supervision index from -0.126 to -0.119 and religion as social bod index from -0.157 to -0.127 respectively. Self-control had the highest positive impact on assault (beta= 0.105), followed by age (beta =0.052), while gender (female) had the lowest (beta= 0. 034) when compared to that of males (beta= 0.054).

4.2. School Delinquency

- When control variables are not factored as in Model 1, all (except a slight difference in family structure) are statistically significant. With control variables, the influence of parental bonding and religion were slightly reduced, while control variables of age, self-control went up high, the remaining were insignificant (beta 0.102 and beta 0.109).

4.3. Public Disturbance

- Without the control variables as in Model 1 religion as social bond index (beta=- 0.155 and family structure index (beta= -0.152) were seen to be statically significant in public disturbance with parental control having the least score. The rest were all statistically significant. With control variables as in Model 2, the independent variables were all reduced in size even though all were statistically significant. Age surprisingly had the least score (beta=-0.025) followed by monetary (beta=-0.029) and gender (female) (beta=-0.032).

5. Discussion

- The findings of this study corroborate those that have found support for the social bond theory. When there is a strong social bonding such as parental and family attachment, strong social institutions with value system, conformity to norms is high. On the other hand, when there is a weak bond to society, with little or no family supervision, the tendency to engage in misconduct is likely to be heightened. It is in this context that this study supports Good (2011), Downs and Rock (2007), Clinard and Meier, 2008) all of which is underscored by the assumption that it is rather weak bonding towards basic social institutions especially basic unit such as the family and value system that could precipitate misconduct. The reason is that individuals lacking control to conform to socially and culturally prescribed norms behave the way they do because of lack of such social bonds as attachment, commitment, involvement and moral beliefs. When the bond of attachment with significant others, especially parents and other members of extended families is strong enough, individuals care a lot about expectations from these significant others that they would refrain from delinquent behaviour. The consistency of the data in both Model 1 and Model 2 above on the four independent variables of family structure, parental bonding and attachment, parental control index and religion as social index is statistically significant. The fact that the same consistency of relationship was not found between some social bonding variables on total delinquency, assault, delinquency in school and disturbances in public is suggestive of the impact of social bonding. This implies that the underlying hypothesis of this research that strong parental and family attachment would reduce delinquency (McCuskey & Tavor, 2003; Worthen, 2012) appears to have been confirmed. In other words, a higher level of social bonding through culturally prescribed norms and values are likely to reduce delinquent behaviour to a lower degree. The control variables did not appear to be consistent all through in terms of statistical significance across all the delinquent behaviors. However, there was some consistent pattern on monetary strain: it had the least scores on all behaviors (beta= -0.034; beta= -0.054; beta=-0.035 and beta= -0.029). This was interpreted to mean that notwithstanding the variance, money or socioeconomic status is least related to misconduct and on two variables of school delinquency and public disturbance they were negatively related. This finding again raises questions about the reliability of those empirical studies linking low socioeconomic status to negative outcomes in behaviour such as Devenish et al, 2017; Piotrowska et al, 2015, Reiss (2013) and many others .The thesis that financial inability to acquire goods increases the risk to delinquent behvaiour (Agnew, Matthews, Bucher, Welcher, & Keyes, 2008) was not found to be the case even though many of the respondents in this study were from less endowed family background. Again the above finding strengthens Sutherland Differential theory and the Social Learning theory (Bandura 1977) that people tend to develop delinquent attitude and skills as a result of continued contact with delinquent people (Wood & Alleyne, 2010) and not necessarily due to economic indigence. Rather, it is the extent to which young people continue to be exposed to attitudes that encourage disrespect for law and order that increases the likelihood of delinquent behaviors rather than economic poverty as such. Religion was found to be related to lowered delinquency on all the dependent variables especially in public disturbance confirming the findings of Brent, Pope and Kelleher (2006).

5.1. Constraints

- There are two seeming constraints in this paper that might set some limitations on the findings: a) measuring scale was mostly done through the use of Likert’s ranking scale. Therefore controlling respondents’ subjective response was difficult; b) This study was conducted in selected schools, yet two important independent school variables were left out, namely, attachment to teacher index as well as school involvement index. This was deliberate, the reason being that the corresponding author would do further investigation to isolate school related variables to examine their moderating influences on delinquent behaviour in a further study.

6. Conclusions

- The findings of this paper provide cross-cultural evidence suggesting that tightly bonded juveniles are less likely to act in delinquent behaviour irrespective of socioeconomic status. Misconduct and delinquent behaviour generally found to be correlated to juvenile from less endowed backgrounds and less so with children from higher socioeconomic background was not supported in this study. No variable was seen to have consistently influenced the reduction of the impact of social bonding besides differential associations reducing a bit when other control variables were factored into the analysis Thus, the orthogenesis of delinquent behaviour is too multifactorial to be subsumed in one or few theories of explanation without cross-cultural verification. In the literature on delinquent behaviours, such as criminality, and other anti-social behaviours, instead of asking why people do not commit crimes, the questions that many research study need to find answers to are rather why people commit crimes. The evidence of this study supports the view that strong regulatory presence of the collective conscience exemplified in social bonding with social institutions that are hinged around strong parental and extended family attachments, religious values, etc. by far mitigate the negative effects of the strain theory that low socio economic status is a leading cause of delinquency.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors thank all respondents who voluntarily participated in this survey.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML