-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2019; 9(1): 9-19

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20190901.02

Does the Socialization of New Managers Start before Hiring?

Jérémie Aboiron

Strat Lab, Neofaculty Europe, Barcelona, Spain

Correspondence to: Jérémie Aboiron , Strat Lab, Neofaculty Europe, Barcelona, Spain.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This article raises the question of the socialization of new managers. Originally we asked ourselves the question about young graduates taking up managerial positions for the first time. But we quickly realized that this organizational socialization issue concerns all new managers, whether they are young graduates or experienced. The issue will be addressed from the perspective of social psychology through the concepts of culture, identity, change management and socialization. We will discover which are the mechanisms that promote the successful integration of new managers, the key success factors for the manager and for the organization. The article does not mention any observations but raises the problem from a purely theoretical point of view. This is a literature review that will have to be enriched by specific empirical approaches to respond more precisely to managerial issues.

Keywords: Socialization, Manager, Organization, Organizational culture, Identity, Change, Digital

Cite this paper: Jérémie Aboiron , Does the Socialization of New Managers Start before Hiring?, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 9-19. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20190901.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The new generation entering organizations today would be "much more demanding on the usefulness of what they do" and particularly committed to making sense of their work. Young people attach much more importance to working together and tend to reject the "rivalry between individuals" induced by traditional management. In addition, this generation would be very much influenced by the importance of work life. These priorities, which are sometimes inconsistent with those of the traditional entrepreneurial world, can lead to difficulties in the socialization of young graduates. Indeed, in the current context of generational crossovers marked by the retirement of baby boomers, this socialization is all the more important for the transmission of knowledge and know-how, as well as for the sustainability of companies.The concept of organizational culture allows us to understand some of the difficulties of integrating young graduates and appears to be one of the key elements for the success of successful organizational socialization. The notion of organizational culture is defined by Schein (1985) as a system of basic assumptions, rules, norms, norms, values and artifacts, invented, discovered or developed by a given group by learning to solve its environmental adaptation and internal integration problems. It has been sufficiently proven to be valid from the group's point of view, and therefore to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, feel and act on these problems. One of the challenges of successful integration into the newcomer group is therefore the transmission of organizational culture, because it gives meaning to the activity. It may be more or less conscious depending on the company and the hierarchical position of individuals, but also on the fact that the integration of standards takes place naturally within the group or is instituted by the hierarchy.Finally, the purpose of this study is to focus on the new manager, whether he or she is a young graduate or experienced but a newcomer to the organization. Indeed, most studies on organizational socialization or organizational culture focus on employees more generally and do not take into account the manager's particular hierarchical position. He will find himself integrated into an organization in which he will have responsibilities and where his team will already be immersed in the company's culture. This arrival is likely to pose difficulties, in terms of, for example, credibility and fear in the face of a possible change in managerial culture.Therefore, we will try to explain how the organizational culture and the contributions of social and work psychology in this field are essential to a better understanding of the organizational socialization of young managers.

2. Organizational Culture

- Every group develops a culture. The fact that groups are working groups does not prevent standardization processes such as the formation of behavioral standards, the differentiation of statutes and the adoption of standards established for any individual who wants to integrate. Work and organizations are to be considered as "producers of culture". This would provide a better understanding of the individual behaviors and strategies, collective functioning and social change processes that organizations are composed of. Reynaud (1989) more precisely defines the different aspects that make up the organizational culture. Norms are the rules and behaviors adopted by the majority and followed by all that make it possible to judge the actions of others. Values are the objectives of action, which is desirable and important to do. And the artifacts represent the visible part of the organizational culture, i.e. the symbols, the layout of the premises, the speech and the jargon used.

2.1. Rules Guaranteeing a Certain Balance

- In the basic assumptions of Schein's theory (1985), when he defines the concept of organizational culture, the purpose of establishing an enterprise culture is to create meaning, which refers to the social demand outlined in the introduction, which is very current. For the author, rules are socially constructed devices that indicate which behavior is appropriate within the group. It distinguishes control rules, which are intended to shape and guide behavior, from autonomous rules initiated by employees, which limit employer control.Reynaud (1989) refers to "joint regulation" between these two categories of rules. In the daily functioning of a work group, the fact that an individual behaves according to the autonomous rules in use shows his integration into the group's culture and makes it possible to define his identity. Non-compliance with these rules is a guarantee of exclusion processes, stigmatization as "deviant", and non-recognition of social belonging to this group.Finally, the concept of "social pacts" developed by d'Iribarne (1989) allows us to recontextualize the regulation of rules according to the national context in which these rules develop. For him, in France, the "logic of honour" prevails, there is a great attachment to social status. Thus, a person would be honourable when his or her behavior corresponds to his or her status and when he or she respects the status of others. The advantage for the manager will be that he will have less need to control the employee, who feels obliged to do his work spontaneously. On the other hand, it will be more difficult to get him to perform tasks of a lower status. Obviously, these results need to be qualified, the aim being not to generalize the processes of creating a corporate culture to each country to which the company belongs.

2.2. The Contribution of Social Identity Theories and Identity Typologies

- Starting from the principle that a person's identity is constituted in relation to the different groups to which he or she belongs, it is obvious that belonging to a work group is an essential support for the individual's construction. Tajfel and Turner (1986) develop several axes essential to the understanding of their theory:• Theory of the minimal group: Belonging to a group, even if it is constituted at random, leads to a differentiation between "them" and "us", without there necessarily being competition or conflict between these groups.• Pro-endogroup bias: The individual seeks to have a positive social identity and therefore has an interest in having his or her own group differentiate positively from other groups.

• Superior self-conformity: The more the individual identifies with his group, the more socially valued it is. In the same way, the more this individual will try to differentiate himself positively from other members of the same group.

• Social comparison: If the group to which the individual belongs is not socially valued, the individual, in an attempt to regain a positive social identity, will develop strategies aimed either at making his group more valued (through creativity, or collective action towards other groups), or at leaving this group if possible (individual social mobility strategy). If social comparison is not favourable, the boundaries between groups are very closed and intergroup differentiation is legitimate, previous strategies are not possible and the individual can then be led to depression.The workplace is considered as a privileged environment for the social development of the individual, each situation mentioned above is applicable in a professional context. Sainsaulieu (1977) provides a classification of workplace identity models. This typology makes it possible to understand the interactions between the strategic capacities of workers, their position in the organization, the nature of their activity and the way they invest in this organization. We can see this approach in terms of the dynamics of appropriation and co-construction of the company's culture. In parallel to the "withdrawal identity" and the "merger identity", Sainsaulieu (1977) defines two types of identity that are interesting for understanding the position of manager: • Negotiation identity: it is also referred to as a position of power. The individual can negotiate his or her involvement in the organization based on his or her hierarchical level or expertise in the organization. The individual brings great value to work and shows solidarity with individuals from the same professional group and rather rivalry with actors with divergent interests. This identity is most evident among professional managers and workers.• Affinity model: these are relatively skilled workers but for whom the importance in work is given to friendly relations rather than power. Work is not enough to define them socially. Rather, they are mobile people who find themselves in this identity. The current context of globalization and the facilitation of business travel suggests that this type of identity will be increasingly developed in the coming years.Finally, Boltanski and Thévenot (1991) establish a typology of the different "common worlds" that makes it possible to explain the conflict resolution processes specific to each environment and between environments. The authors assume that market mechanisms are not the only form of coordination of economic actors. They postulate that there are "collective cognitive devices", in other words, rules and representations sufficiently shared by everyone to coordinate social life within the organization. These rules would also serve as an aid in deciding on the right behaviour to adopt in an a priori uncertain situation and would facilitate dispute settlement. These common worlds have a common higher principle that organizes the world, an image or metaphor that symbolizes this principle. They include the idea that there are "big" and other "small" ones. From one world to another, these reports do not concern the same characters. They are distinguished by a repertoire of typical subjects and objects and modes of relationship typical of each world. Finally, tests make it possible to deal with disputes and to know who is right or wrong, who is large or small. In particular, they define three worlds related to the workplace:• The commercial world: characterized by the notions of buying, selling, negotiating, competing, competing, competing, pricing, financial results and profits.• The industrial world: characterized by control, formalization, forecasting, experts, operators and specialists. The standards of this world will refer in particular to technical standards and control methods.

• The project world: characterized by the temporary mobilization of a network of actors, project managers, mediators, coaches and communication technologies. Here the norms of relationships refer to connection, communication, coordination, but also to trust, the ability to adjust to others and intense engagement. For the authors, this world would be a way for capitalism to renew itself by assimilating the diffuse social practices that influence our economic world in an uncertain and unstable way. This world induces career management and the mobilization of networks in autonomy for individuals, and therefore pressure due to the value of internality.

2.3. Change Management

- The concept of organizational culture specific to each working group also initiates the idea that this culture is shifting because the group is made up of individuals who are likely to leave the working group and new entrants can integrate it. Difficulties can therefore be apprehended with regard to cultural change. However, cultural change is not a phenomenon to be systematically considered in a negative way. Lewin (1947) states that changing an individual's behavior is the result of a change in the "force field" of the group's norms and pressures. To persuade an individual to change, we must also place ourselves at the level of group dynamics. It distinguishes three stages of culture change:

• De-crystallization, which corresponds to dissatisfaction with old norms of behavior, an awareness of the group's difficulties, a loss of sense of certain values, etc. The group and its members will convince themselves that change is necessary.

• Displacement, i.e. learning new values and creating new standards.• Recrystallization, which refers to the institutionalization of new practices, consistency of standards and recognition of the movement made. This is a very important phase so that individuals do not return to the old behaviors abandoned in the second stage.This theory allows Lewin to introduce the notion of resistance to change, which he sees as a consequence rather than an explanatory factor. When an individual or group has more to lose than to gain in change, when information and participation are sufficient, resistance to change is rather an expression of a healthy reaction to a poorly thought-out change. Thus, the experience of Coch and French (1948) shows the importance of informing, explaining and, above all, involving employees in the implementation of this change in order to prepare for organizational change, so that the creation of new standards is possible and to consolidate new individual behaviors. Pettigrew (1987) defines the dimensions of successful change. These three dimensions require good interaction (mutual adaptation) between them for success. The failure of one of these dimensions, such as overly ambitious content, absent or poorly thought-out processes or inappropriate context, can lead to failure.• The content of the change, which represents the goals, objectives to be achieved and concrete elements to be modified;• Context refers to the characteristics and challenges of the internal and external environment, but also to the capacity of the people concerned to appropriate change;• The process corresponds to the implementation of the procedure according to the persons involved. It is very important to adapt the context to the content and to adapt the content to the context.Lewin takes the example of the Concorde case, a high-performance aircraft produced in an unsuitable context (for example, it would have required equipped runways, a specific fuel, it can only hold a maximum of 100 people). Here, no change process has been put in place to adapt the aircraft to a commercial use market, only the financial support of France and Great Britain has allowed its short survival.

3. Theoretical approach to Organizational Socialization

- Faced with this organizational culture which, as we have seen, is present in each work organization, in a more or less conscious and accepted way, the young manager will have to adapt to the habits and rules of the company in which he arrives. We will expect it to become a vehicle for transmitting the values, rules and standards of the company's culture. It therefore seems essential that the organizational socialization of this individual be successful. Feldman (1981) defines organizational socialization as a process by which an individual outside the organization is transformed into a participatory and effective member. The quality of this socialization will determine the attachment of new entrants to the company, the acquisition of the company's own know-how and a desire to pursue a career in the organization. However, today, in times of job shortage, recruiters tend to focus on selecting candidates rather than on their organizational integration. In this context, it seems very important that adaptation also takes place from the organization to the individual.

3.1. Organizational Socialization of Newcomers

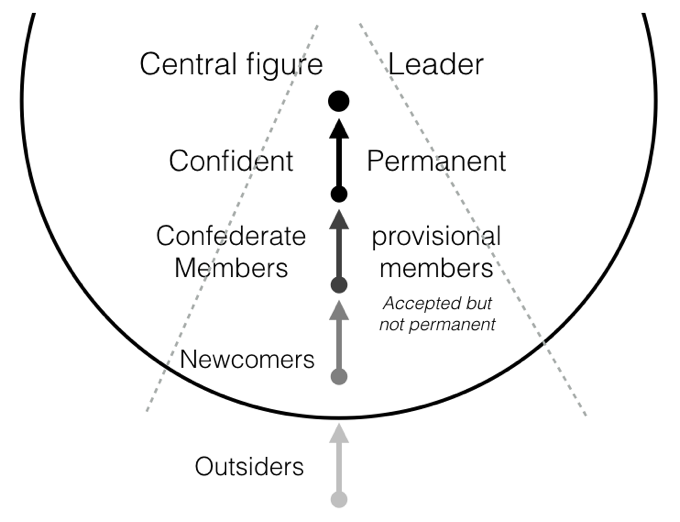

- In Schein and Van Maanen's (1977) founding model, it is stated that organizational cultures are born and maintained as a way of adapting and giving meaning to a given problematic environment. New members always bring with them at least one potential for change. They may, for example, question old assumptions about how work should be done, be ignorant of some of the almost sacred interpersonal conventions that define authority relationships in the workplace, or fail to properly understand the work ideology or organizational mandate shared by the more experienced actors in the company. New managers from different backgrounds bring with them misconceptions about the job they will have to do, including their mistakes, and perhaps values and goals that do not correspond to the new environment.More experienced members must then find ways to ensure that newcomers do not disrupt ongoing activity, embarrass or cast a derogatory light on others, or overly challenge previously established cultural solutions. New members must learn to see the world of organization in the same way as their more experienced colleagues if the organization's traditions are to be sustainable. The way in which this teaching/learning is done is referred to here as the process of organizational socialization. In a more general sense, organizational socialization is the process by which an individual acquires the knowledge and social skills necessary to assume an organizational role.In this model, one of the most important and fundamentally interactive dimensions is the inclusion of an individual within the organization. For a variety of reasons, newcomers, in most hierarchical and functional levels of organizations, inevitably remain on the margins of organizational affairs for some time after their arrival. They may not yet be considered trustworthy by other group members, or as not properly meeting the expectations of other group members.We will recognize in the diagram the whole issue of the manager's socialization, since he is expected to move from being a newcomer to being a leader in the time available, often very short.

| Figure 1. Inclusionary Domains of organizations |

3.2. The Specific Organizational Socialization of New Managers

- For this part, we have relied on the writings of Fabre and Roussel (2013) concerning the influence of interpersonal relationships on the organizational socialization of young graduates and those of Boussaguet (2008) concerning the socialization of SME buyers. Thus, according to Fabre and Roussel, the good interpersonal relationships that the newcomer maintains with his peers would allow him to benefit from a model and support that would facilitate learning and socialization. Therefore, the quality of interactions with company members would promote the acquisition of appropriate behavior or role, the development of work skills, adjustment to work group norms and values, and an understanding of organizational norms and procedures (Reichers, 1987). The authors develop their theoretical model around three concepts based on social exchange that deal with the quality of the relationships between the employee and his three main socialization agents. These concepts provide a precise interpretation of the exchange relationships between the employee, his or her colleagues, his or her supervisor and the organization as a whole.• The Leader Member eXchange (LMX) is defined as the quality of the exchange relationship between the superior and the subordinate. This is reflected in mutual expressions of support in work, professional trust (leading, for example, to autonomy, participation in decision-making), good understanding and loyalty (Liden and Maslyn, 1998).• Team Member eXchange (TMX) refers to the quality of the relationship between the employee and his or her work team (Seers, 1989). The purpose of this concept is to measure the member's perception of his or her own willingness to assist peers, share ideas and provide feedback, as well as the degree to which he or she perceives receiving information, assistance and recognition from other members of the work unit.• Perceived Organizational Support (POS) represents the quality of the social exchange relationships between the employee and his or her organization. This corresponds to an employee's overall belief in the degree to which the organization values his or her contribution, and is concerned about his or her well-being (Eisenberger et al., 1986).In their results, they demonstrate that TMX has an impact on the relational aspects of business life, as well as on the mastery of cognitive elements (knowledge of history, internal politics, language and task), while POS has an impact on the emotional level, on attitudes towards the organization. LMX appears to be more particularly associated with the emotional and relational aspects of socialization. These results indicate that there is a clear separation in the support provided to young graduates during periods of socialization, between organizational, hierarchical and peer support.They also demonstrate that organizational support is linked to adherence to organizational goals and values. This is directly explained by the mechanism of social exchange, for which a favour received by the employee in return gives rise to positive attitudes of the employee towards the organization. If the organization is perceived as caring about the well-being of its employees, it induces a sense of ownership of the organizational culture. Thus, employees would tend to respond to organizational support with a commitment to the organization, while in return for their work team, this would translate into a specific involvement with that team.Thus, good interpersonal skills with the supervisor will encourage the formation of a sense of ownership of organizational goals and values, suggesting that the supervisor is seen by young graduates as the "agent" of the organization, through which it acts and expresses itself.Boussaguet (2008) offers us a manager's point of view on the socialization of business owners. According to him, it is important to properly manage the integration of newcomers:• At the organizational level, it is necessary to be able to preserve the knowledge, know-how and skills that have made it possible to make things work in the past. The arrival of new members must not lead to dysfunctions (through the loss of information, synergy or intangible capital); they must preserve internal balances, at least before it is possible to transform or develop them.• At the individual level, newcomers must be allowed to build themselves by reorganizing their assets or experiences in the new context of the company. The aim is for them to be quickly effective in terms of cognition (perception of the situation), relationships (interactions with other members) and techniques (mastery of management tools); they must be recognized as well adapted to their new environment.

4. An Ontological approach to Socialization

- In an epistemological reflection on the concept of socialization of managers, we can ask ourselves the purpose: what is a manager who has successfully socialized with his organization? But we could also be interested in the question of how an organization can create socialization? Can we say that there is a culture of socialization of new employees?We carried out observations of thirty managers in small, medium and large structures. We will see later what the results are. The evaluation of this socialization is not without its methodological problems. Indeed, evaluation is an activity whose objective is to make an empirical and normative judgment on the value of an action, project or policy in order to reach reliable conclusions applicable to a particular context.In the service of decision-makers, evaluation helps to make decisions. It therefore focuses on objectively measuring the effectiveness and sustainability of an action by highlighting its conditions and consequences. In our case, it is about the socialization of managers.Objectivity is in this case a guarantee of the quality and accuracy of the information, insofar as this objectivity is based on rigorous evaluation methods and tools and as long as it remains independent of the actors who will implement the action, the project evaluated, to avoid possible conflicts of interest likely to influence the evaluation results.The evaluation also consists in ensuring the relevance and coherence of the objectives, i.e. verifying the adequacy between the objectives to be achieved, the context and the means implemented, which is a prerequisite for the conduct of the intervention.The main role of evaluation is therefore to reduce uncertainty about the strategy adopted or to be adopted, by acquiring information that is supposed to be reliable and objective.We will agree that it is important to differentiate evaluation from other activities that can be assimilated to it because their objectives are very similar. For example, when we undertake an evaluation, control or audit process, or even research, it is always a question of improving the project, whether in its operation or its performance. However, the angle of study adopted differs somewhat. The audit of an organizational structure consists in collecting objective information to ensure that rules and procedures are followed. The objective here is to improve the company's efficiency, as is the case for evaluation. However, the audit differs from the evaluation in that it does not take into account the relevance and impact (consequences) of the project under review: it does not call into question the very existence of the project. In addition, in the audit, the emphasis is often placed on the individual skills of the actors concerned. These competencies are also assessed, which is not the case in the assessment. In addition, there are the different forms of control that use internal standards of the analyzed system as a reference value for their judgment, while the evaluation, which must be objective, takes an external point of view when measuring the project under consideration. She is critical of the data.According to Cohen (1997), evaluation "encompasses a set of practices, theoretical or technical knowledge and discourse related to the conduct of organizations in general", these three domains have the same purpose: "the mastery of the theoretical or empirical, cognitive or operational problems posed by the implementation of a potential, that is, a set of diversified resources gathered within an organization, within the framework of the objectives and constraints assigned to that organization".Elie Cohen also points out in her article that management "takes into account the influence of the economic variables that pass through the organization and the regulatory variables that determine it". According to this grid, management therefore mainly studies the conditions for the survival and development of organizations by adopting their vision from both a theoretical and a practical point of view.As we know, any evaluation approach is likely to be biased, which therefore hinders the optimal usability of the evaluation work carried out. Other obstacles, more qualitative than quantitative, limit the effectiveness of evaluation.The many methodological obstacles have been studied by Cook (1975), Angelmar (1977) and Nioche (1982). We will group here the most frequently observed biases.As each member of the evaluation committee is an individual in its own right, with a personal history, personal experiences, convictions, opinions, preferences, and interests in the success or failure of the evaluation as well as its direction, the question arises as to the extent to which a minimum of objectivity can be achieved in the conduct of the evaluation. So how can we ensure that the conclusions of the evaluation will be based on the reality of the facts and not on the orientation in a particular sense of them? Influential groups may favor some conclusions and reject others, as is the case with lobbying.We must therefore bear in mind that this measure does not have the value of absolute truth since it only represents an assessment of a situation determined at a particular time by a particular evaluation team. The conclusions are therefore likely to be challenged, incomplete, partially biased. A lack of perspective can be detrimental to the assessment in terms of credibility. The same applies to the processing of data, the method of which may be biased or controversial. Data processing may be more problematic than expected.With regard to the data themselves, there may be unreliable data and information, supernumerary data or data that are too complex. It should also be noted that it may also be difficult to clearly distinguish the causal relationship, the responsibility that may exist between all the factors that come into play in the evaluated project when there are too many of them.The method used to process the data may also be questioned. When comparing in the evaluation, several biases are likely to be identified. Indeed, in the case of a comparison, it is necessary to constitute two random samples composed of target populations. One of the samples will be submitted to the evaluated action and the other not. Such a method is based above all on reasoning: it is supposed to make it possible to take into account and reason only on variables studied, assuming that all exogenous variables act in exactly the same way. In practice, this is not always verified or verifiable. Moreover, it may seem illusory to hope to compare groups that are not equivalent. Indeed, by setting up two groups, one of which would have been affected by an action related to the project evaluated, strict equivalence between each group is not guaranteed insofar as the difference concerns a criterion that is endogenous to the evaluation. Methods of causality analysis may also be subject to the introduction of different biases. Thus, when modelling data, we generally try to verify that there is a match between the model and what we actually observe. This approach does not in any way justify and validate causal relationships, which is why the results obtained from statistical modelling are only reliable if they are applied to a coherent model based on sound theoretical arguments.The causal approach to social phenomena faces another obstacle: the phenomenon of circularity. Circularity is defined as the existence of two phenomena that can simultaneously cause and effect each other, making the analysis more complex and error-prone.Apart from the methodological obstacles that we have just seen, it is important to stress that Nioche distinguishes two main societal, political or institutional obstacles in France. The so-called socio-political obstacles and the so-called administrative obstacles. The first type of obstacles includes what the author calls the Jacobin tradition, according to which a decision emanating from a legitimate and recognized authority is necessarily optimal and would not need to be evaluated using formal methods, and then French intellectual culture, which would favor, on the one hand, decision-making tasks, considered the most noble, and, on the other hand, doctrinal debates on the task considered the most ungrateful of the administration of evidence in empirical research, an essential task in the context of evaluation. Finally, the importance of an administrative culture that has favored punitive control over constructive diagnosis does not favor the development of evaluation.These characteristics are part of the societal aspect of this first group of socio-political obstacles.However, it seems important now to pose, to expose our reality. In the current state of our research, this reality is essentially philosophical. We must therefore interpret this philosophical conception, which we have partially explained earlier. We will be able to do this largely through a hermeneutical approach to the subject matter.Hermeneutics is a philosophical approach to understanding and interpreting reality, as Gadamer (1975) explains. Indeed, this author is one of the founding fathers of this new way of interpreting truth based on a construction and method that goes beyond the simple philosophical approach. Thanks to hermeneutics, it is a question of interpreting the role of the actor but above all of considering that his role as an actor is ultimately less important or strongly correlated to the reality of the system that lives thanks to his action.In the case of the socialization of new managers in an organization, this means that the organization's actions, its development, its successes and failures are its own and are not the sum of the actions of the actors. On the other hand, it makes sense here that the good socialization of managers is part of something bigger than them because it is a concept of shared culture, beliefs and values.This understanding of the reality we have just outlined may be a simple preunderstanding of a reality that remains to be interpreted. A necessary foundation for the construction of a larger conceptual building that will shed light on the importance of this notion of engagement.Gadamer (1975) agrees with Heidegger (1973) on the notion of understanding. According to them, there is a real difference between being and knowing. This difference is the foundation of modern hermeneutics. We then understand that in the conception of socialization there is a fundamental difference between knowing the organization and the individual.To continue, it is important to question the link that may exist between reality and knowledge. It is difficult for us to think, or simply to consider, that reality can be knowledge or that our knowledge can be reality. As we have seen above, reality is an interpretative construction with its own biases. Reality being the result of a perception specific to each person, even if points can meet, it is nevertheless a construction of reality. It must therefore be stated that our knowledge can in no way be the reality, it will be a reality. The paradigm through which we have constructed our reality and our knowledge already assumes that we will diverge from other paradigms and therefore build a different reality and knowledge of that reality.We understand that our perception and positioning in relation to reality and knowledge is constructivism. We will adopt a form of methodological passivity towards the object because we wish to propose ideas and/or build a theoretical concept. As we will see later, our qualitative methodological approach will allow us to produce a knowledge built to explain or interpret facts, a social phenomenon.According to Le Moigne (1995), "the knowable reality has a meaning in itself and that this meaning does not necessarily depend on the personal preferences of observers who try to record it in a form of determination". Knowledge is therefore relative. It relates to the research object itself, our ability to produce knowledge, the quality of that knowledge, external contingency factors, intent, interactions and all the other factors that have constructed reality, that modify it and that allow us to interpret it. Our hermeneutical approach described above brings us closer to a postmodernist epistemology in that for us, reality is unstable and shifting. But also, as Le Moigne (1995) points out, "reality is built by the act of knowing", it is in this respect that our epistemological approach is based on an engineering constructivism. Indeed, it will be a question for us of interpreting a behavior by linking it to its purpose(s).

5. Methodology

- We observed about thirty managers from their recruitment process to six months after their recruitment. There are three meetings during which we observed them and collected their speeches and feelings about their integration.The sample is composed of as many women as men, aged 30 to 50, in different industrial sectors. This sample is mainly a convenience sample.We used the grounded theory as a methodology. Glaser & Strauss' (1967) Grounded Theory is described as a research method in which the researcher's theory is constructed from data, rather than the other way around. This approach is therefore defined as inductive, i.e. it moves from the specific to the most general. The study method is essentially based on three elements: the concepts; the categories; and the proposals.Categories that can also be called research hypotheses. In this method, concepts are the key elements of the analysis since the theory is developed from the conceptualization of the data, rather than the actual data.Strauss & Corbin are two of the greatest advocates of the model and define it as follows: "the theory-based approach is a qualitative research method that uses a systematic set of procedures. Develop a grounded theory by induction on an observation phenomenon". The main objective of grounded theory is to develop an explanation of a phenomenon by identifying the key elements of this phenomenon, then categorizing the relationships of these elements with the context and process of the experience. In other words, the goal is to move from the general to the specific without losing sight of what makes the subject of a study unique. Here we will work on the observation of a social phenomenon in the context of innovation networks, and more particularly competitiveness clusters. This qualitative approach is perfectly suited to the needs of the research and the subject under study.It should be noted that ingrained theory is often seen as a method that separates theory and data, but others insist that the method combines the two well. Data collection, analysis and theory formulation are undeniably linked in a reciprocal sense. And the theory-based approach incorporates explicit procedures to guide this. This is particularly evident in the sense that according to the established theory, the processes of asking questions and making comparisons are specifically detailed to inform and guide the analysis and thus facilitate the theorizing process. For example, it is expressly stated that research questions must be open and general rather than formed as specific hypotheses, and that the emerging theory must take into account a phenomenon relevant to participants. This, as we will see later, will be implemented in the interview guide for interviewees.There are three distinct but overlapping analytical processes in the ingrained theory on which sampling procedures are typically derived. These are: open coding; axial coding; and selective coding.Open coding is based on the concept of data "cracking" as a means of identifying relevant categories. This is a decoding of the data in categories. Axial coding is most often used when the categories are at an advanced stage of development. And finally, selective coding is used when the "main category", or central category that correlates all the other categories of the theory, is identified and linked to other categories.As we have just seen, the term "grounded theory" refers to the theory developed in an inductive way from a body of data. This means that the resulting theory should correspond perfectly to a data set. This contrasts with the theory derived deductively from the great theory, without the help of data, and which may therefore not correspond to any data at all.The ingrained theory takes into account a case rather than a variable perspective, although the distinction is almost impossible to establish. This means that we will take different cases to be sets, in which the variables interact as a unit to produce certain results. A case-oriented perspective tends to assume that variables interact in a complex way and is wary of simple additive models, such as ANOVA with only the main effects.The part and subpart of the case study is a comparative orientation. Similar cases on many variables but with different results are compared to target where key causal differences may be found. This is based on John Stuart Mills' (1843) difference method, which focuses mainly on the use of experimental design. Similarly, cases with the same outcome are examined to analyze what conditions are common to all, revealing the necessary causes.The approach to grounded theory, in particular the way Strauss develops it, consists of a set of steps whose careful execution is supposed to "guarantee" a good theory as an outcome. Strauss would say that the quality of a theory can be assessed by the process by which a theory is constructed.The fundamental principle that guides the use of grounded theory is the need for a systemic understanding of the world. Do not try to apply a theory to the world, that is, do not want to put individuals in a box, but ask them what their box is. It is therefore the respondents themselves who tend to define their categories and explain implicit belief systems.The basic idea of the grounded theoretical approach is to read, reread and read again a textual database, such as a corpus of field notes, and to discover or label variables, also called categories, concepts and properties, in order to understand their interrelationships. The ability to perceive variables and relationships is called "theoretical sensitivity" and is affected by a number of factors, including reading the literature and using techniques designed to improve sensitivity.Of course, the data do not have to be literally textual, in our research they may consist of behavioral observations, such as interactions and events. Often, they are in the form of field notes, which are like journal entries.For our research we use an open coding method. Open coding is the part of the analysis that concerns the identification, naming, categorization and description of the phenomena found in the text. Essentially, each line, sentence, paragraph, etc. is read in search of the answer to the repeated question: what is it?These labels refer, for example, to elements such as hospitals, information gathering, friendship, social loss, etc. They are the nouns and verbs of a conceptual world. Part of the analytical process consists in identifying the more general categories in which these elements are bodies, such as institutions, professional activities, social relations, social outcomes, etc.We also look for adjectives and adverbs, i.e. the properties of these categories. For example, about a friendship, we could ask ourselves about its duration, its proximity and its importance for each party. Whether these properties or dimensions are derived from the data itself, from the respondents or from the researcher's mind depends on the research objectives.It is important to have fairly abstract categories in addition to very concrete categories, because abstract categories help to generate the general theory.Not to mention the process of naming or labelling things, categories and properties, which is also known as coding. Coding can be done in a very formal and systematic way or rather informally. In the established theory, this is normally done informally. For example, if after coding a lot of text, some new categories are invented, grounded theorists generally do not return to the previous text to code this category. However, it is useful to maintain an inventory of codes with their descriptions (i.e. create a codebook), as well as pointers to the text that contains them. In addition, as codes are developed, it is useful to write memos known as code notes that discuss codes. These notes become the material for further development.Strauss and Corbin consider it vital to pay attention to processes. It is important to note that their use of "processes" is not quite the same as the concept of "explanatory mechanism". In this research, we will really focus on describing and coding everything that is dynamic in the context of our research object.Before considering the effects of knowledge, it seems important to us to recall as an axiology point of view what valuable knowledge should be. The fact that it is valid for a knowledge means that it must be true. The true exists in the field of verifiable. What others can observe, control and therefore verify. Indeed, we will then have to link all the methodological concepts with our ontological and epistemological approach to justify the validity of the knowledge. Valuable knowledge ensures that in a given context others can establish the same observations and build the same knowledge. Then we can say that our knowledge is valid. Validity necessarily requires processes and tools that ensure that we measure what we are supposed to measure.The knowledge we are going to create through our epistemological point of view is not necessarily worth the knowledge of others and vice versa. Let us also remember that for Popper (1972) a knowledge is scientific if it is refutable. A risky hypothesis would then be much more interesting from a scientific point of view.Our valid knowledge, i.e. the true one, will not be scientific knowledge but rather an adequacy. In our constructivist approach, it seems more relevant to us to talk about adequacy because the knowledge we will create will be the right one. Taking up the unstable and shifting nature of our object, it becomes quite relevant to affirm that our truth is relative. Our knowledge will be the result of a process of observation, analysis and understanding. The in-depth study of specific cases will allow us to draw a generalization that will then become our knowledge thus created. If in our work we can collect enough details and descriptions, then we can make this knowledge actionable in other contexts and thus make it functional.The knowledge we are creating through this research will certainly have an effect. In the literature, the effect of this knowledge is in the form of "performativity". There are two main definitions. The first one by Lyotard (1979) results in the best ratio between the data collected and the results obtained. That being said, Lyotard insists on the fact that there is a risk between reducing collection efforts and increasing the results obtained. This implies an ability to generate profit from valid and easily mobilized knowledge outside the scientific context. In this context Lyotard points out that the more a knowledge is proven, the more likely it is to be irrefutable. The instrumentalization of research and knowledge inevitably has an impact on all stakeholders.According to Krieg-Planque (2013), "performativity", and therefore the effect of knowledge, includes all the effects produced by the simple fact of stating the object. In this case we will then talk about speeches. The effect of the discourse will have a direct or indirect impact on stakeholders. However, for there to be an effect, the speech must be long-term and carried by a legitimate person.In summary, we note that our research work would most certainly have one or more effects on the objects studied, even if they are social phenomena and in particular engagement in a meta-organization. Let us now ask ourselves how our reality can nourish our knowledge, that is, how our perception of reality and our knowledge interact in our journey, while analyzing the effects that this can have.

6. Results and Challenges of Socialization

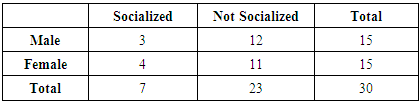

- From our observations we have obtained as a result that there is no difference between men and women in the phenomenon of socialization.

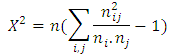

With a calculated Chi2 of 0.186, which is lower than the critical Chi2 of 3.84, this confirms that being a man or a woman has no impact. Since our sample represents a population of only 30 individuals, we consider that this may be different on a larger scale or in a specific sector.On the other hand, what is recurrent in the discourse of individuals, male or female, is that socialization in an organization is linked to culture. In order for good socialization to take place, it begins before recruitment, through interactions with the company and its employees. These interactions are primarily through social networks, with spontaneous responses in order: 1. Linkedin; 2. Facebook; 3. Blog.This first phase of socialization is described by individuals as a phase of understanding and appropriation of the organization's culture. Some have even gone so far as to say: "it is a way of identifying with the group".We now understand that the socialization of new managers is a major challenge for the proper functioning of organizations. Indeed, if the organization does not take this fundamental issue into account, it is very likely that it will severely penalize the organization's performance and proper functioning. It is not clear that the coercive power that the organization can exercise over individuals is free of this problem, quite the contrary.As we have seen above, it is therefore important to ensure that new managers are welcomed. This welcome can be provided by the Management itself as part of a framework policy for welcoming new employees, or by the team itself, which will be responsible for transmitting to the new manager the values and culture of the organization and the team more specifically. It is by ensuring that these elements are properly communicated to newcomers that the organization can continue to operate without organizational disruption. The construction of this socialization is different for each group of individuals and could be improved by using specific tools and/or procedures.It is important to note that if there is no particular integration, the individual will respond on his or her own, with his or her own values, perception and situation resolution process. This will lead to extreme or confusing situations for employees or the entire organization.The new manager must take ownership of the organization's rules in order to ensure the continuity of the service. But this is also the case when the organization wants to change its way of doing business or its culture. In the latter case, it will also be necessary to appropriate the rules and culture of the organization before being able to develop it/them.

With a calculated Chi2 of 0.186, which is lower than the critical Chi2 of 3.84, this confirms that being a man or a woman has no impact. Since our sample represents a population of only 30 individuals, we consider that this may be different on a larger scale or in a specific sector.On the other hand, what is recurrent in the discourse of individuals, male or female, is that socialization in an organization is linked to culture. In order for good socialization to take place, it begins before recruitment, through interactions with the company and its employees. These interactions are primarily through social networks, with spontaneous responses in order: 1. Linkedin; 2. Facebook; 3. Blog.This first phase of socialization is described by individuals as a phase of understanding and appropriation of the organization's culture. Some have even gone so far as to say: "it is a way of identifying with the group".We now understand that the socialization of new managers is a major challenge for the proper functioning of organizations. Indeed, if the organization does not take this fundamental issue into account, it is very likely that it will severely penalize the organization's performance and proper functioning. It is not clear that the coercive power that the organization can exercise over individuals is free of this problem, quite the contrary.As we have seen above, it is therefore important to ensure that new managers are welcomed. This welcome can be provided by the Management itself as part of a framework policy for welcoming new employees, or by the team itself, which will be responsible for transmitting to the new manager the values and culture of the organization and the team more specifically. It is by ensuring that these elements are properly communicated to newcomers that the organization can continue to operate without organizational disruption. The construction of this socialization is different for each group of individuals and could be improved by using specific tools and/or procedures.It is important to note that if there is no particular integration, the individual will respond on his or her own, with his or her own values, perception and situation resolution process. This will lead to extreme or confusing situations for employees or the entire organization.The new manager must take ownership of the organization's rules in order to ensure the continuity of the service. But this is also the case when the organization wants to change its way of doing business or its culture. In the latter case, it will also be necessary to appropriate the rules and culture of the organization before being able to develop it/them.7. Conclusions

- This study first allowed us to better understand the importance of organizational culture and organizational socialization concepts in the workplace. Then, we can see that the contributions of social psychology, such as Tajfel and Turner's theory of social identity or Pettigrew's culture of change, are added values for the understanding of the manager's profession. Finally, the success of the organizational socialization of a new manager is a major challenge for the organization, whether public or private. This should be compared with the phenomenon of acceptance and integration of organizational culture, which is a major challenge for the newcomer. The success of these two processes is the guarantee of stable interprofessional relations and the commitment of the various members of the organization to its strategy and objectives.It is important to note that this literature review makes it possible to open up reflection on several fields of research and in particular to observe empirically the realities concerning the socialization of new managers in different types of organizations. There may be differences by sector of activity, size of organization, etc.The intercultural approach has already developed organizational training for companies sharing different national cultures and facing communication difficulties. One way to train new managers in intercultural differences within organizations could be to adapt these types of training to smaller groups, to the different units of the company.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML