-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2017; 7(5): 117-129

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20170705.03

Art-of-Living: A Model and the Development of the Art-of-Living Questionnaire (AOLQ)

Claudia Anette Stumpp-Spies, Bernhard Schmitz

Department of Psychology, Faculty of Human Sciences, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany

Correspondence to: Claudia Anette Stumpp-Spies, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Human Sciences, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

How should I live my life in order to gain satisfaction in my personal life? The modern industrial world proposes technical innovations, global exchange, media, and increasingly reduced moral standards as answer to this question and offers an endless number of lifestyle options promising personal satisfaction. However, as for the philosophers in the past, questions such as “how to lead a good life” and “what is the essence of art-of-living” are still prominent in all layers of society and modern lifestyles. We developed a theoretical psychological model for art-of-living, which is based on philosophical considerations and combines philosophic elements with human resources and individual strategies. We then used this model to develop a questionnaire measuring art-of-living, which we validated based on the data from 224 individuals. In total, 22 scales including 4 items each were assessed. Evaluations showed that the AOLQ outcome predicts participant well-being measured with the “Subjective Happiness Scale” (SHS). In addition, we also found correlations with specific personality characteristics (“Big Five Inventory”, BFI-K). Very good psychometric properties could be shown for the AOLQ – e.g., high internal consistency and factorial validation as well as convergent, predictive, and incremental validity. Our results also indicate that optimism, romantic relationships, enthusiasm, learning, and partnership/family are important aspects of individuals’ art-of-living. Further revision of the AOLQ resulted in a practical tool that can also be used to create individual profiles of the art-of-living components.

Keywords: Art-of-living, AOLQ, Well-being, Optimism, Satisfaction with life

Cite this paper: Claudia Anette Stumpp-Spies, Bernhard Schmitz, Art-of-Living: A Model and the Development of the Art-of-Living Questionnaire (AOLQ), International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 7 No. 5, 2017, pp. 117-129. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20170705.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- “Vivere vis: Scis enim?” – “You want to live? Do you know how?” (Nickel, 2011, p. 31). This ancient philosophical question, which Seneca posed so provocatively, is one of the central questions of human existence. Today, the question is more relevant than ever before, because people have more choices in how they live their lives. With this increase in possible choices in the past centuries, the art-of-living concept has also changed: it has many more facets than in ancient times and is related to different philosophical schools. What remains is Seneca’s above mentioned question and its underlying skepticism, which leads to many additional questions: Why is life not something that can be taken for granted, something that happens on its own? Why are some people seemingly incapable of leading a “good” life? What are they lacking? Is it something they could learn?In the current study, we aim to help answer these questions by first developing a theoretical model of the art-of-living that combines philosophical elements with human resources and individual strategies. We then use this model to develop a questionnaire measuring art-of-living, which we validated based on data from 224 individuals. In the following, we will first discuss important areas of overlap and distinctions between art-of-living and related psychological concepts such as well-being, life satisfaction, resilience, and sense of coherence.

1.1. Philosophical Roots of the Art-of-living

- The philosophy of the art-of-living centers around the comparison of different contemplations regarding how one’s life can be conducted in an ideal manner. At first, the art-of-living was considered to be philosophizing. In Europe this idea has its roots in ancient Greece. The beginnings of this idea were created by the Seven Sages, including, for example, Thales of Miletus. They developed the first categorical imperatives as a behavioral guide for how people should live their lives, including: “Know thyself.” “Nothing in excess.” and “Know thy opportunity”. (Werle, 2000). When developing his ethics, Plato (fourth century BC) focused on the pursuit of wisdom (sophia) and the achievement of self-knowledge (Fellmann, 2009). Since Plato’s time, sovereignty – in addition to the concerns of the city – continues to be a central concept. In his dialogues with Socrates, the following points are especially important: people must be critical of themselves and consider life’s central questions and, when doing so, they must consult others to ensure the correctness of their perspectives. Later, in addition to naming and describing the classic virtues, Aristotele’s Nichomachean ethics laid out the central concepts of a reflective art-of-living: each individual has the choice to achieve happiness (eudaimonia) and excellence through practical judgement (phronesis) (Schmid, 2012). Aristotle – in addition to emphasizing self-love and self-friendship – was also the first to mention the importance of social relationships and friendships. According to Aristotle, it is only through social relationships that an individual can obtain self-sufficiency (autarkeia). In the century following, this way of thinking was expanded upon by the cynics as well as Epicurus, who philosophized about self-mastery (Schmid, 2012). An important aspect of the ancient philosophy of the art-of-living was the concept of mastery through practice. It is only through practice that one can successfully achieve certain virtues and happiness. This act of working on one’s self was thought to strengthen the self (Schmid, 2012).In their age, the stoics (e.g., Epictetus, Seneca) showed a great interest in not only theoretical discussions but also specific rules governing how individuals should live their lives. They understood the art-of-living in its original sense: as a life craft (techne tou biou), just as in the literal translation of the original Greek term. Not only did they attribute great importance to reason as an individual’s ability to act morally and control their emotions. Rather, their understanding of the art-of-living also focused on concrete rules of behavior that individuals should follow. For example, it combined the ideas of necessity and freedom. That is, there are many things in life where an individual can exercise free choice. However, some necessities in life cannot be changed. For this reason, stoics should willingly follow the things in life that they cannot change. In doing so, they can achieve inner freedom even in situations beyond their control (Fellmann, 2009). Brennan (2005) and Sharples (1996) provide a detailed overivew of ancient Greek philosophy. Fellmann (2009) summarized the development of the Hellenistic art-of-living in the following way: “With that, the formal meaning of the Hellenistic art-of-living becomes relevant. Unlike in classic ethics, it does not deal with the clarification of general moral concepts. Nor does it concern the objectives for raising young individuals but, rather, individual techniques for achieving a lifetime of learning” (p. 58, translated by the author). Hadot (1995) described the philosophy of that period as a “way of life”. At the end of their philosophical journey, individuals should achieve an “inner transformation”. For this reason, Hadot viewed classical philosophy as a form of therapy: philosophy should strengthen individuals mentally, spiritually, and physically. Hadot emphasized the notion that all classical philosophical schools of thought originally stem from spiritual practices (e.g., meditation) aimed at achieving and enhancing wisdom. It was only approximately 1,000 years later, in Humanism and the Renaissance, that the art-of-living once again became a topic of philosophical discourse. In the previous centuries, the art-of-living as a concept remained uninteresting due to a pervasive Christian-medieval view of humankind. A life defined by religious paternalism allowed individuals little space for self-study and the pursuit of a good life. With Montaigne, who created the foundation for moralism, the 16th century saw a return to “the philosophy that teaches us to live” (Schmid, 2012; translated by the author), i.e., the art-of-living. As Fellmann (2009) emphasized, Montaigne did not believe that individuals should adhere to specific rules of virtue. Rather, through education and personal experiences they should come to know themselves and become the type of person that is consistent with their constitution. Then, during the moralism era of the 17th and 18th centuries, the stoic principles received attention once again. As Schmid (2012) noted, the focus lay on the development of a practical, everyday way of life. In the 19th century, Schopenhauer developed his own philosophical concept wisdom of life. For Schopenhauer, living meant suffering; thus, he believed the mere presence of pain was a sign of great happiness. Still, he spent a great amount of time discussing happiness and named three sources thereof – one’s own being, property, and prestige – the first of which he deemed the most important (Fellmann, 2009).Nietzsche also developed a philosophy of the wisdom of life, which centered around the idea of self-determination introduced in the classical period (Schmid, 2012).In the 20th century, the traditional philosophical discourse concerning the art-of-living was briefly taken over by psychology, psychoanalysis, and psychotherapy. According to Freud’s psychoanalytical perspective, individuals are hindered in their pursuit of happiness by the three parts of the human psyche – the id, ego, and super-ego. Freud believed that individuals must work to strike a balance between these conflicting parts.Victor Frankl’s logotherapy also had an important influence on the philosophy of the art-of-living. Erich Fromm, too, addressed the art-of-living in his works, in which he noted a strong ambivalence: he considered the art-of-living to be the most important yet also most difficult and complicated art (Dohmen, 2003).

1.2. Adapting Art-of-living to Modern Life: A Reflective Art-of-living

- As discussed above, the philosophical art-of-living changed very much over time. Interestingly, the changing concept often returned to its Greek roots, which even today are still highly relevant. The world has since changed markedly; individuals now live under completely different conditions and demands. Yet, individual needs today are still similar to those in the past – humankind has remained human.What does that mean for the art-of-living? How can one’s life be successful today? Today, everything seems possible – what consequence does that have for modern life? The omnipresent expectation to fill one’s life with happiness and well-being – which also appear omnipresent – does not necessarily make the choice between the seemingly endless possibilities any easier. Even the US American constitutional right to the pursuit of happiness is of little help. Indeed, it may even increase the subjective pressure experienced by the individual. At the end of one’s life, who wants to have the feeling that their life was unhappy or even “wrong”? Or even the feeling that one did not take advantage of all available opportunities? Likely no one.Thus, how do modern art-of-living concepts address the question “How should I live my life?” Dohmen (2003) defines the modern art-of-living as a type of self-determination with the goal of a good life. Thus, he himself propagates an authentic art-of-living.In Dohmen’s (2003) overview of the modern art-of-living, it becomes clear that modern (Michel Foucault), conservative (Pierre Hadot), and liberal (Wilhelm Schmid) concepts have become meshed together. Yet Dohmen (2003), like many other authors, no longer focuses solely on ethical virtues and virtuous living; instead, he seeks to provide a plausible and modern answer to the question “How should I live my life?” In his opinion, the definition of a good life is dependent on one’s personal motivations. These motivations must first be identified based on one’s most important personal values as well as how they can be developed further and whether or not they are legitimate. Thus, Dohmen views the art-of-living as a learning process. When individuals base their lives on authenticity, their actions are always justified, regardless of whether they follow existing rules. Dohmen believes that this is the most important aspect of the art-of-living.Modern authors on the art-of-living are apparently in agreement that the Aristotelian concept of a good life in philosophic discourse is once again relevant.Hadot (2001) also holds that view. Based on Marcus Aurelius (121-180 A.D.), Roman emperor and stoic, and his “meditations”, Hadot encouraged a return to a form of practical philosophy as a “way of life”. He also criticized modern philosophy for being too academic and neglecting the concept of a good life. Veenhoven (2003a) traded the singular concept art-of-living for the plural – thereby discussing different Arts-of-living. He first differentiates between two different types: the virtuous life and the enjoyable life. The virtuous life is strongly oriented around rules and ideals, whereas Veenhoven describes the enjoyable life, which includes greed and jovialness, as an almost hedonistic art-of-living. Still, he also describes a third form – the happy life – in which quality of life arises not from enjoyment but rather sustained satisfaction with life in general. Csikszentmihalyi (2010) is a prominent advocate of this school of thought who defines happiness as “flow” – a skill he believes practically everyone is capable of improving. According to Csikszentmihalyi, an autotelic self is necessary for such improvement, meaning that one can easily change potential threats into positive challenges, seldom experiences fear, is never bored, and actively takes part in surrounding occurrences. The term autotelic self literally means “a self that sets its own goals”. The philosopher Wilhelm Schmid is considered an advocate of a very liberal school of thought whose impressive work systematically changed the philosophical art-of-living. In the past few years, Schmid has published several works on a modern, reflective art-of-living (Schmid, 2000a, 2000b, 2007, 2012, 2013).Schmid (2000a) believes that modern individuals are generally capable of taking advantage of the opportunities they are presented with in life: “Live your life in a self-affirming manner!” With this existential imperative, Schmid attempts to encourage individuals to use their personal options in life to their own advantage.According to Schmid, the concept of a self-affirming life does not refer to a perfect or optimal life but rather one that is rich with opposites and contrasts. Schmid’s (2007) art-of-living concept requires self-knowledge and related techniques necessary to obtain self-determination. Individuals can only decide what type of life they would like to lead if they first possess self-knowledge and an awareness of their own personal values. Thus, self-knowledge represents the starting point for everything else, including possible changes to one’s current situation.

1.3. Relationship between Art-of-living, Well-being, and Positive Psychology

- There is a close relationship between well-being, positive psychology, and art-of-living. We will first define the elements of positive psychology, well-being, happiness, and life satisfaction and then discuss their relationship to art-of-living. Then, we will explain the resulting assumptions adopted as a basis for the research described in the current paper.In everyday language, well-being, happiness, and life satisfaction are often used interchangeably. In the academic literature, however, there is a clear differentiation between happiness and well-being vs. life satisfaction. Diener, Diener, and Diener (1995), for example, defined happiness, or subjective well-being, as “people’s cognitive and affective evaluations of their lives” (p. 851). Thus, they use the terms happiness and well-being synonymously. Pavot and Diener (2008), in contrast, state that life satisfaction is merely a component of well-being that can be measured with the SWLS (Satisfaction With Life Scale) developed by Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin (1985). The fact that well-being is not simply a cost-benefit calculation was described by Wong (2011) in his modern definition of well-being: “According to PP 2.0, well-being is not the algebra of positive minus negative plus negative. In other words, the capacity to transcend and transform negative provides an additional source of well-being to positively based well-being” (p. 75). In Wong’s definition, the individual is also held responsible – not only as someone who attributes subjective value to his or her life but also as someone who can actively turn negative aspects of life into positive ones, which then become additional sources of well-being.What connection do these concepts have to art-of-living? Art-of-living is, on the one hand, a distinct concept that provides the philosophical foundation for psychological research on these concepts and, thus, belongs to the field of positive psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Diener, 2000; Deci & Ryan, 2008). However, when examining the relationship between art-of-living and well-being, one must first determine the direction of the relationship – i.e., which is the predictor and which is the outcome. Veenhoven’s (2003a, 2003b, 2014) classification of ways of leading a good life – which differentiates between life chances and life results – provides an important basis on which to answer this question. Life chances include life-ability, which consists of a person’s physical health, mental skills, and life-style skills. According to Veenhoven (2003b, 2013), one must have the “inner quality“ of possessing sufficient resources to achieve well-being or happiness – these may include “invisible” skills and resources as well as “visible” strategies, which serve as a demonstration of what a person does to achieve well-being. In the following study, we will demonstrate empirically that art-of-living is related to psychological concepts such as well-being and life satisfaction.Recently, Schmitz (2016) also provided statistical results indicating significant relationships and differences between art-of-living and concepts relating to character strengths (p. 64). Schmitz also demonstrated that art-of-living correlates significantly with constructs such as resilience (.68), sense of coherence (.69), self-regulation (.61), and wisdom (.58) (p.71-72).

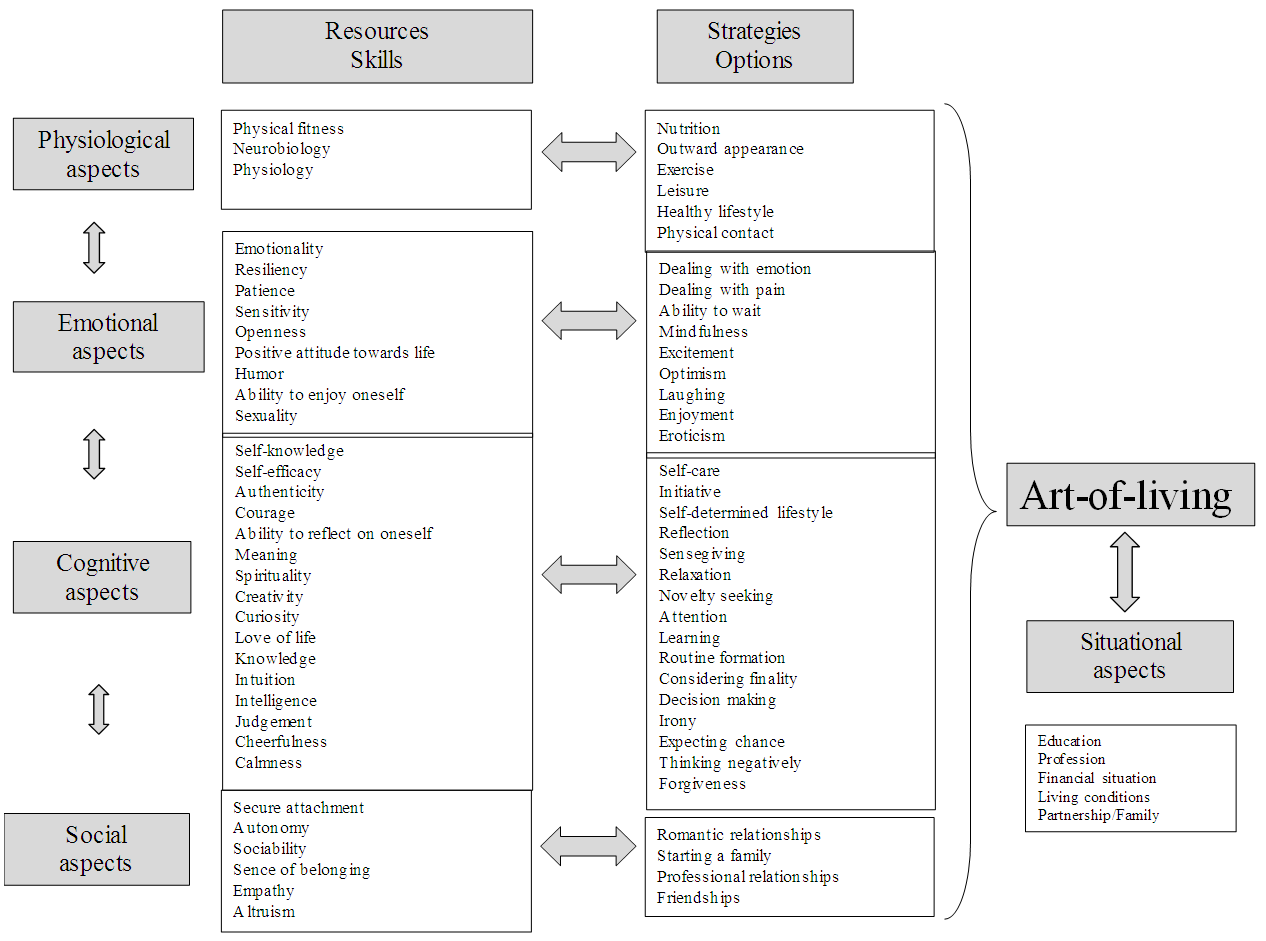

2. From Philosophy to Psychology: The Development of a Theoretical Art-of-living Model

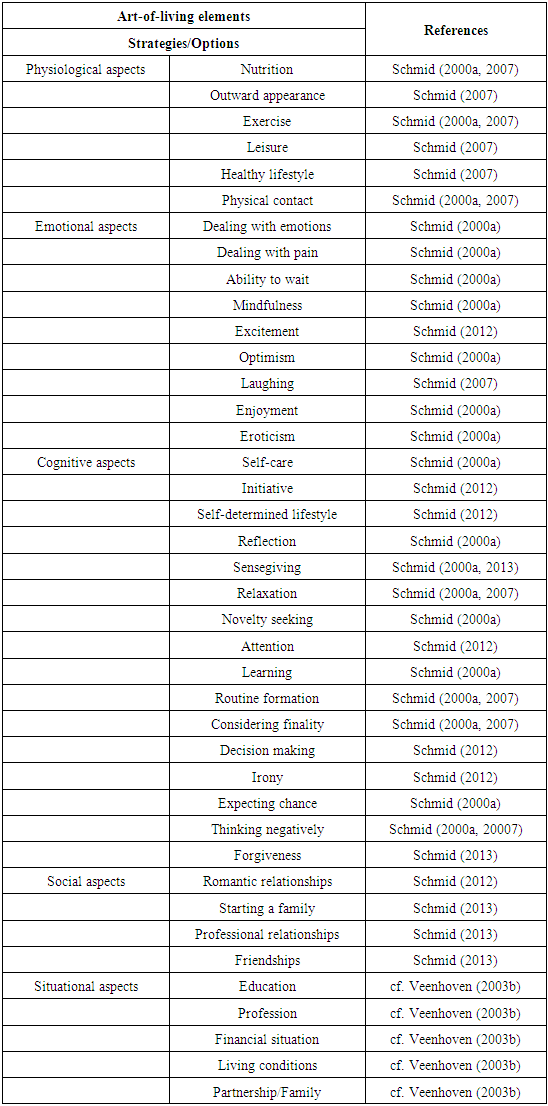

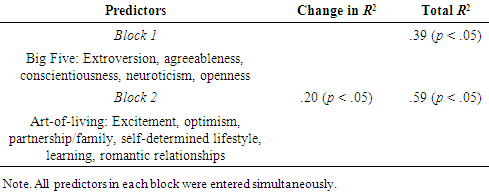

- Referring back to Seneca’s question introduced at the beginning of this paper as well as Veenhoven’s classification (2003a, 2003b, 2013, 2014), we posed the following question. Assuming one seeks to understand how to live: What resources and related strategies would one need? This question should lead to the development of a questionnaire that measures art-of-living.There has already been one empirical attempt to construct a questionnaire measuring art-of-living. Schmitz and Schmidt (2014) developed a questionnaire containing 14 scales including a total of 79 items, which achieved satisfactory results in terms of statistical parameters. With that, they were able to demonstrate a correlation between art-of-living scores and life satisfaction – an important first step towards empirically examining art-of-living from a psychological perspective. However, because the definition of art-of-living on which the questionnaire was based did not include several important life areas (e.g. sexuality and romantic relationships), we sought to develop a questionnaire that addresses the entire modern art-of-living concept. To do so, we first constructed the art-of-living concept and systematically organized the relevant life areas in order to obtain a comprehensive description of the concept. We based this description on the works of Wilhelm Schmid (2000a, 2012), who in recent years has both developed a modern definition of the art-of-living as well as systematically structured existing philosophical art-of-living concepts. His collection of art-of-living elements and techniques serves as the foundation for our psychological model, which provides a comprehensive overview of the art-of-living construct (Figure 1).

|

2.1. Description of the Different Art-of-living Aspects and Related Scales

- In the following sections, we will describe in detail the scales and their philosophical roots.Physiological aspects: In his book “Being your own friend”, Schmid (2007) describes concerns about one’s own body – including having selective eating habits (nutrition)and taking care of one’s outward appearance – as one of humankind’s main concerns. In addition, Schmid believes that individuals should use exercise for physiological self-care in order to become the master of one’s own body. Thus, in addition to exertion, i.e. exercise, one should seek to achieve relaxation, i.e. through leisure. According to Schmid (2007), one means of becoming the master of one’s own body is a healthy lifestyle including preventative behavior. Schmid (2007) relates physiological contact with a type of sensuality, which also contributes to self-care of the body.Emotional aspects: Emotional self-care, as well, is also of great importance according to Schmid (2007). He views emotions and pain as a personal challenge. The ability to wait until the appropriate point in time to do something rather than simply letting time pass by is also important in Schmid’s (2000a) view in terms of the constructive use of time. Mindfulness, too, is seen as a valuable strategy that is necessary in many life areas – an important factor of relevance here is also time.Schmid (2013) describes how satisfying it is, for example, to read literature with excitement. Excitement (Csikszentmihalyi would use the term flow) is thus an art-of-living strategy. Although the term optimism is not used by Schmid (2000a) directly, he does mention the importance of maintaining a positive attitude. A positive attitude and easy-going cheerfulness can both refer to an optimistic outlook on life – i.e. optimism regarding one’s ability to successfully handle difficult situations. Laughing, enjoyment, and eroticism are combined by Schmid (2000a) in the overarching concept of eliminating concerns, which implies that individuals satisfy their desires but do not overindulge.Cognitive aspects: The concept of self-care is of central importance to Schmid (2007) and includes diverse forms of taking-care-of-oneself. The scale self-determination refers to an individual’s active and creative influence on life occurrences. According to Schmid (2007), self-determination also means that individuals actively shape their own environments. Such a self-determined lifestyle becomes evident in his existential imperative: “Live a self-affirming life.” (Schmid, 2000a). Schmid (2012) views reflection as an important strategy to maintain distance to oneself. That is, one reaches a meta-level from which to view oneself objectively. The term sensegiving includes the defining word giving. Thus, objective meaning is not contained in things or actions; rather, it is actively given by an individual. In his book “Giving life meaning”, Schmid (2013) describes several possibilities of sensegiving. Time is required for relaxation with which one can make room for new ideas and experiences (Schmid, 2000a). Novelty seeking, according to Schmid (2012), is considered by many philosophers to be the mark of a free spirit that allows one to experience new things. Attention is a strategy that Schmid (2012) considers necessary in many life areas in order for individuals to be sensitive to their own needs, e.g. in order to make good decisions. Schmid (2012) encourages individuals to avoid being apathetic; instead, they should engage in continual learning as a means to achieve excellence. Through a network of routines, thoughts and actions require less effort. The goal here, according to Schmid (2000a), is developing skill, as thoughts and actions occur repeatedly and thus become more reliable. In Schmid’s (2000a) view, a traditional practice in the art-of-living is contemplating death, i.e. considering finality, which can lead to a new outlook on life. Schmid (2012) views decision making in modern times as a special challenge for the self and modern art-of-living. Irony allows individuals to objectively see things with humor – Schmid (2000a) sees this as an important life strategy, since knowledge and art-of-living come together in irony. For Schmid (2000a), art-of-living also means expecting chance and even taking advantage of chance occurrences to go in new directions. He is highly critical of the modern mania of positive thinking (Schmid, 2000a). Instead, he advocates the advantages of negative thinking. Positive thinking leads to pressure on the self to succeed. This is not the case for negative thinking; rather, surprises become possible and disappointment becomes less likely. It is entirely up to the individual to avoid retaliation in the face of conflicts (Schmid, 2013). This is an act of forgiveness in the general sense, as the individual voluntarily forgoes compensation for a wrong that they experienced.Social aspects: Schmid (2013) believes that relationships are the defining factor in terms of the meaning of life and, with that, the art-of-living, as well. According to Schmid, individuals strive to achieve a successful art-of-living when they are not driven by individualistic arrogance. Instead, they attempt to live a self-determined life, establish a reflective relationship to themselves as well as strong relationships with other individuals, and participate in shaping society (Schmid, 2000a). These relationships consist of romantic relationships, friendships, and professional relationships as well as starting a family.Situational aspects: Living conditions also have on influence on individuals’ art-of-living. They also represent factors that individuals can change. These factors include education, profession, financial situation, living conditions, and partnership/family.

2.2. Demarcation between Strengths of Character and Art-of-living

- Peterson and Seligman (2004) made an important contribution to positive psychology with the development of their Values in Action (VIA) classification of strengths. With the help of a comprehensive literature review, including both philosophy and psychology, the authors identified 24 character strengths, which they then classified into six different virtues. They then developed a questionnaire based on their classification – the VIA-IS (Values in Action Inventory of Strengths) – which measures the degree to which an individual possesses each character strength. Using this questionnaire, they then demonstrated that all 24 strengths (with the exception of modesty) are positively correlated with life satisfaction.Peterson, Ruch, Beermann, Park, and Seligman (2007) tested the classification character strengths in diverse populations. The results of this study indicate that the character strengths with the strongest relationships to life satisfaction are also related to “orientations to pleasure”, “engagement”, and “meaning”.In general, these character strengths are of relevance when empirically examining art-of-living, as both concepts are somewhat related. For example, both include love of learning, curiosity, and forgiveness. However, the modern art-of-living concept remains distinct from mere virtues or character strengths. On the one hand, the philosophical art-of-living, as displayed in our model (Figure 1), focuses on considerably more areas than character strengths. On the other hand, morality is much more relevant to character strengths than the modern art-of-living, which has much less to do with moral judgment and contains no explicit moral imperatives. In their classification of character strengths, Peterson and Seligman (2004) selected only those that were “morally valued in [their] own right” (p. 19). Art-of-living makes no moral judgments. Instead, it offers strategies for leading a good life. Thus, art-of-living focuses much more on actions and behavior. An additional difference between art-of-living and the classification of character strengths is that the latter represents a universal and culturally independent concept. Art-of-living, in contrast, is based on European philosophical roots and western ways of thinking. It is this population that forms the focus of this paper – the extent to which our findings are generalizable to other populations must be addressed in future research.

2.3. Research Questions

- We sought to validate our art-of-living questionnaire by first reducing the number of items using exploratory factor analysis and then testing its construct, convergent, predictive, and incremental validity. In doing so, we examined the relationships between the scale and other concepts including participant well-being and personality traits.

3. Method

3.1. Sample

- Participants were recruited through advertisements in the journal “Psychologie Heute” and by flyers at public places. In total, 224 individuals took part in the study. 164 participants were female. Mean participant age was 42.06 years (SD = 14.07).

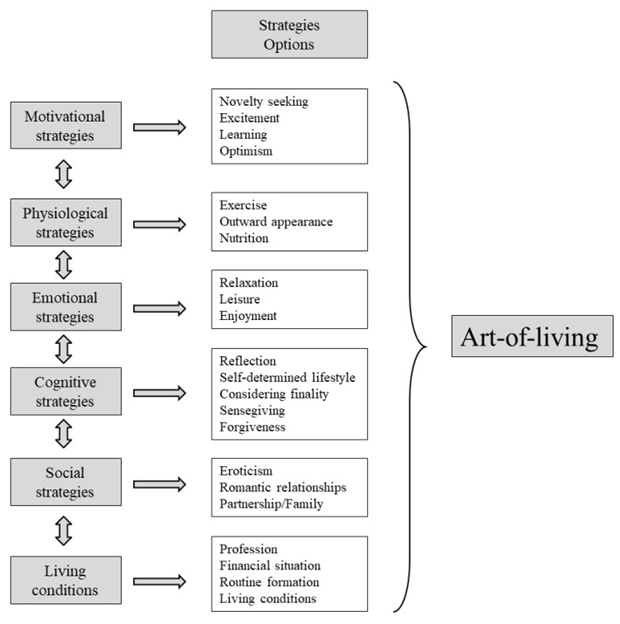

3.2. Procedure

- The theoretical art-of-living model discussed above formed the basis for questionnaire development. For each of the 40 scales (Figure 1), we formulated four items aimed at identifying which respective strategy respondents are using. What do they do? Which of the options available to them do they choose? The scales and example items describing the respective strategy are displayed in Table 2. All items were answered on 6-point scales (1 = not at all true, 2 = not true, 3 = somewhat not true, 4 = somewhat true, 5 = true, 6 = very true).

| Table 2. Subscales with example items |

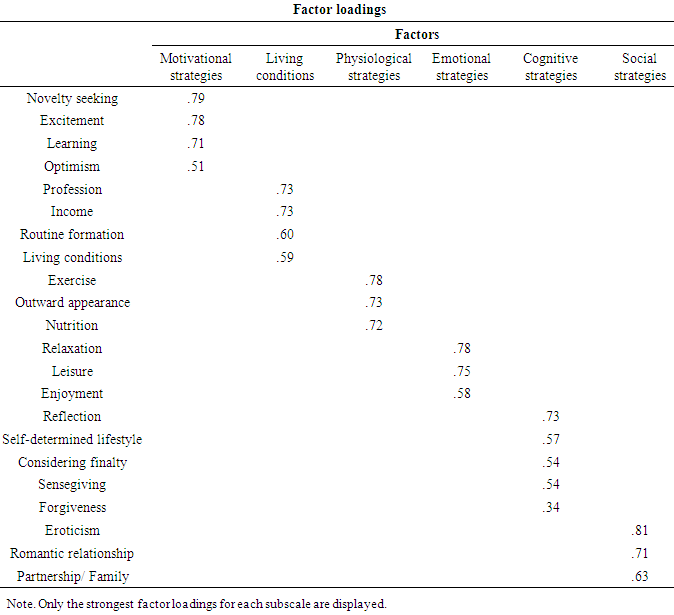

4. Results

- We first used Cronbach’s α measure of internal consistency to assess the reliability of all 40 scales (4 items each) from the questionnaire. Results indicate high reliability for both the overall scale (α = .97) and all but four subscales (values between α = .60 and α = .88). In a second step, we excluded the four unreliable subscales (i.e., healthy lifestyle, ability to wait, attention, decision making). We then conducted an exploratory factor analysis using varimax rotation of the remaining 36 subscales in order to further simplify the art-of-living construct. In doing so, we excluded 14 redundant subscales, resulting in a final result of 22 subscales. Thus, the following 22 subscales formed the simplified AOLQ, which was then used in all analyses of the above mentioned research questions: learning, excitement, novelty seeking, reflection, optimism, self-determined lifestyle, considering finality, routine formation, sensegiving, relaxation, leisure, self-care, exercise, outward appearance, nutrition, eroticism, romantic relationships, partnership/ family, forgiveness, profession, financial situation, and living conditions. The factor analysis of these 22 subscales is summarized in Table 3.

|

4.1. Reliability and Validity

4.1.1. Internal Consistency

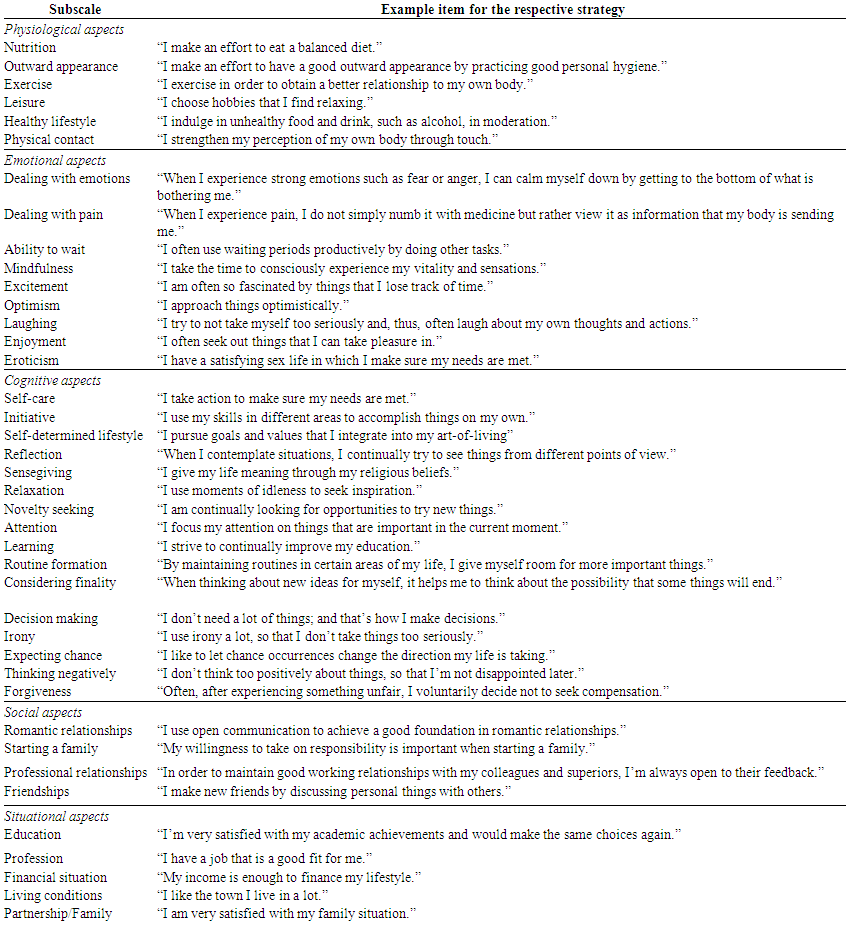

- Examination of the internal consistency of the simplified art-of-living questionnaire indicates high reliability across the 22 subscales (Cronbach’s α = .89). Internal consistency for most subscales is sufficiently high (α > .70), although Cronbach’s α lies between .60 and .70 for some subscales and α > .80 for others. Values for all subscales are displayed in Table 4. Overall, these findings indicate that all subscales are associated with at least satisfactory internal consistency.

4.1.2. Construct Validity

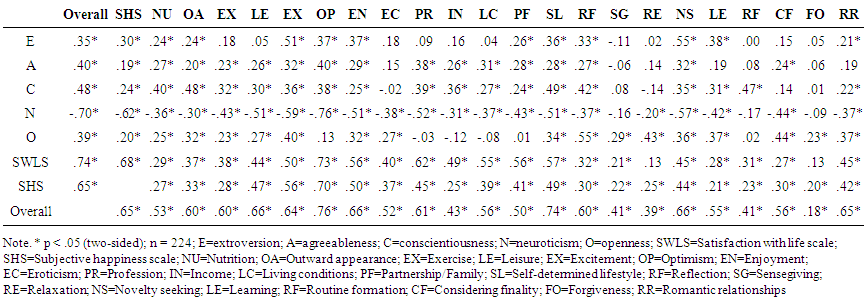

- The bivariate correlations between the individual scales as well as the correlations between the overall scale and the respective subscales are generally high and significant (r > .50). Only a small number of subscales are associated with weaker correlations (r < .50). Thus, we found empirical support for the notion that art-of-living is a higher order construct. All correlations are displayed in Table 4.

| Table 4. Descriptive statistics, correlations, and reliabilities of the subscales |

4.1.3. Convergent Validity

- As an additional validation measure, we computed the correlations between art-of-living and the individual Big Five scales (all correlations are displayed in Table 5). As expected, art-of-living correlates positively with openness for experiences (r = .39, p < .01), extroversion (r = .35, p < .01), agreeableness (r = .40, p < .01), and conscientiousness (r = .48, p < .01).

| Table 5. Correlations between subscales and other instruments |

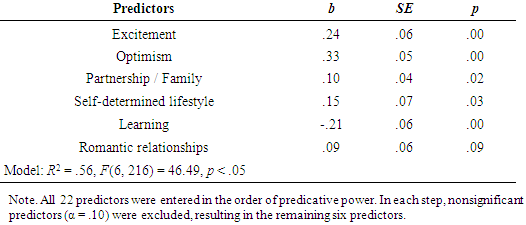

4.1.4. Predictive Validity

- To test the predictive validity of the simplified AOLQ, we calculated a step-wise multiple regression with all 22 art-of-living subscales as predictors and participant well-being (SHS) as the criterion. Subscales were entered in the order of their predictive power regarding well-being. In each step, subscales that no longer predicted well-being were excluded. The results indicate that optimism, romantic relationships, excitement, learning, partnership/family, and self-determined lifestyle significantly predict well-being (p < .10). All other predictors were excluded (see Table 6 for all regression coefficients). Together, the six significant subscales explain more than half of the variance in participants’ reported well-being (R2 = .56) and can thus be viewed as potentially important art-of-living strategies.

|

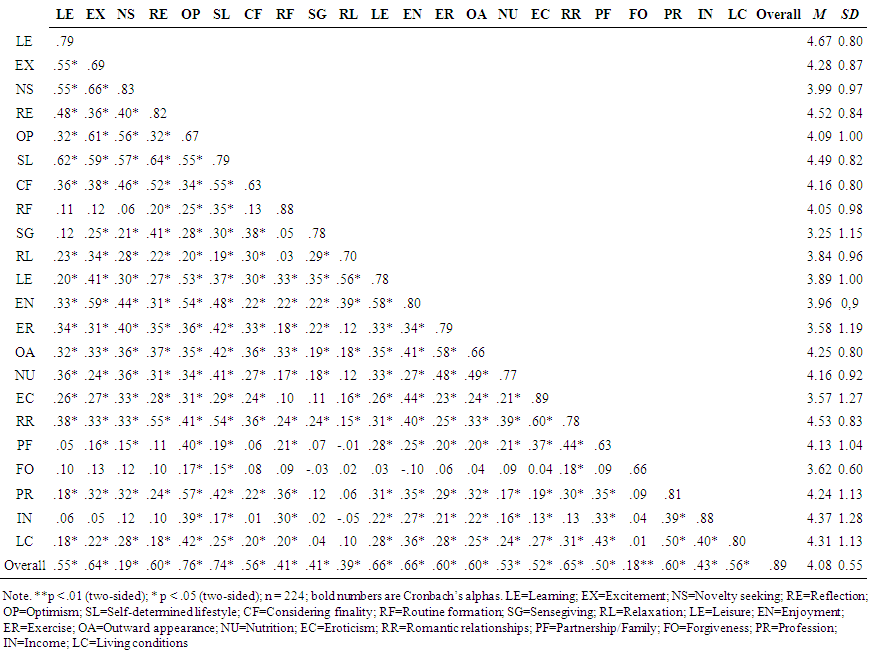

4.1.5. Incremental Validity

- In order test whether the art-of-living scale predicts well-being above and beyond the predictive power of previous measurement instruments, we computed a step-wise multiple regression analysis (using well-being as the criterion variable) in which we entered all five Big Five scales first as a block followed by the six art-of-living variables identified in the stepwise multiple regression above as a block (results are displayed in Table 7). Results indicate that the Big Five scales significantly predict well-being (R2 = .39, p < .01). The analysis also provides support for the incremental validity of the art-of-living scale developed in this paper, in that the art-of-living variables significantly explain variance in well-being (change in R2 = .20, p < .01) above and beyond that explained by the Big Five scales.

|

4.2. Optimized Psychological Model of Art-of-living

- Based on the results of the factor analysis (Table 3), we created an optimized psychological model of the art-of-living (Figure 2). The model overlaps substantially with the theoretical art-of-living model displayed in Figure 1. Thus, we found empirical support for the definition of the art-of-living posited in the introduction.

5. Discussion

- This study is a valuable first step in the development of a psychological art-of-living model based on the complex philosophical concept of Wilhelm Schmid. Our AOLQ based on this psychological model represents a practical measurement instrument for assessing an individual’s personal art-of-living score. The preliminary questionnaire contained 40 subscales including a total of 160 items. Of those, we selected 22 subscales including a total of 88 items to construct a short form of the questionnaire with sound psychometric qualities. The next step in future research should involve the modification of the psychological art-of-living model with the goal of optimal congruency between the model and the short form of the AOLQ.One finding of this study gives the relevance of predicting the overall art-of-living by some art-of-living subscales. Statistical analyses later indicated a hierarchy of importance among the subscales: optimism, romantic relationships, excitement, learning, partnership, and self-determined lifestyle all appear to play an important role in terms of a successful art-of-living and high life satisfaction. It is important to note that one finding was not to be expected a priori based on the philosophical literature: optimism appears to be an important element in one’s art-of-living. This finding was unexpected, as optimism, specifically, is not discussed in the philosophical literature in terms of being an especially important element of art-of-living. Schmid (2000a) does mention – as discussed earlier – serenity and a sense of easy-going cheerfulness. However, he was not referring to positive thinking or general optimism. Rather, he was referring to a person’s ability to autonomously handle all life experiences even negative ones. Schmid’s understanding of easy-going cheerfulness is similar to our concept of optimism, which we define as the ability to approach life and its challenges with confidence. Optimism does not mean that one always expects good things to happen; but rather that one will always be able to find the best possible solution in difficult situations. In addition to optimism, our findings indicate that excitement is also an important concept. According to the neurobiologist and brain researcher Gerald Hüther (2012), excitement is “fertilizer for our brains” (p. 92, own translation). That is, it is extremely important, as it leads to the release of neurotransmitters that help build new neuro-networks. Interestingly, our findings also provide empirical support for the large effect of relationships – especially romantic relationships – on one’s art-of-living. Thus, a successful art-of-living appears to be dependent on strong social relationships and not just (primarily) one’s self and self-determination. We do not find this notion entirely surprising – in romantic relationships, two individuals with unique ideas concerning their art-of-living come together. These “arts of living” must then be aligned and harmonized with the help of communication, which brings with it many of its own difficulties. Thus, Wilhelm Schmid’s (2000a) existential imperative “Live your life in an affirmative way” is not sufficient in practice, as it concerns only the individual and ignores the influence of his or her social relationships.An additional interesting finding is that the linear regression shows no meaningful effect of physiological strategies on participants’ art-of-living scores. One possible explanation for this disparity is that physiological aspects are contained in other variables.Our results indicate a significant relationship between art-of-living, well-being, and life satisfaction. This was an important finding in terms of convergent validity. Other correlations indicate significant relationships with personality aspects measured with the Big Five. A potential weakness of this study is that the short version of the AOLQ is still rather long with 22 subscales comprising 88 items – shorter measurement instruments certainly exist. However, the art-of-living concept is just as complex as life itself. Thus, it does not make sense to further reduce the number of subscales. Especially since the AOLQ could potentially form the foundation for the development of a program to improve individuals’ art-of-living. The development of such a program based on only a few isolated subscales would not sufficiently take the complexity of life and the art-of-living into consideration. In addition to the focus of this study, the data contain diverse art-of-living subareas and subscales that lead to new research questions. The art-of-living construct is so complex that our psychological model and resulting measurement instrument represent only a first step in this research area.It is likely that art-of-living – even more so than strength of character and virtue – is related to the concept “human flourishing” (cf. Fredrickson & Losada, 2005). This relationship should be examined in future research. Cultural differences in art-of-living also represents a valuable topic for future research.

6. Conclusions and Outlook

- This study provides support for the notion that art-of-living can be measured empirically and provides a validated measurement instrument. In addition, our findings lay the groundwork for the development of a training program to improve individuals’ art-of-living. Such a program would represent an important bridge between ancient philosophical discourse on individual art-of-living and the facilitation of individual improvement. In addition, the measurement instrument developed in this study allows for the identification of specific art-of-living subscales in which individuals scored especially poorly. This could potentially be used to construct personalized intervention programs. Generic interventions that do not take individual needs into consideration are likely unsuccessful in achieving long-term, positive change in individual art-of-living. The necessity of and desire for first steps in creating programs to facilitate successful art-of-living is stressed by Veenhoven (2003b), who named his article “Notions of art-of-living”: “Another promise is that art-of-living may be a practicable venue for intervention. Personality cannot be changed easily but appropriate skills can be learned to some extent. Hence, it is worth knowing what these skills are and how they can be approved. The editors welcome further contributions on this subject” (p. 349).Returning to Seneca’s initial question “Vivere vis: Scis enim?” – “You want to live? Do you know how?”: our art-of-living questionnaire (AOLQ), in a first step, can help individuals better understand which areas of their lives are important to their art-of-living as well as which areas could be changed in order to improve their art-of-living scores. However, when Seneca said “Do you know how?”, he actually meant “Can you do it?” That is, understanding alone is not enough. Thus, the development of appropriate interventions, as well as experimental tests of their effectiveness, would be helpful in enabling individuals to improve their art-of-living.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML