-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2017; 7(4): 86-95

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20170704.02

An Investigation of Youth Basketball Players' Participation Motivations and Relate Elements

1Brooklyn College of the City University of New York, USA

2Education Research Institution of Jiangsu Province, Nanjing, China

Correspondence to: Howard Z. Zeng, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

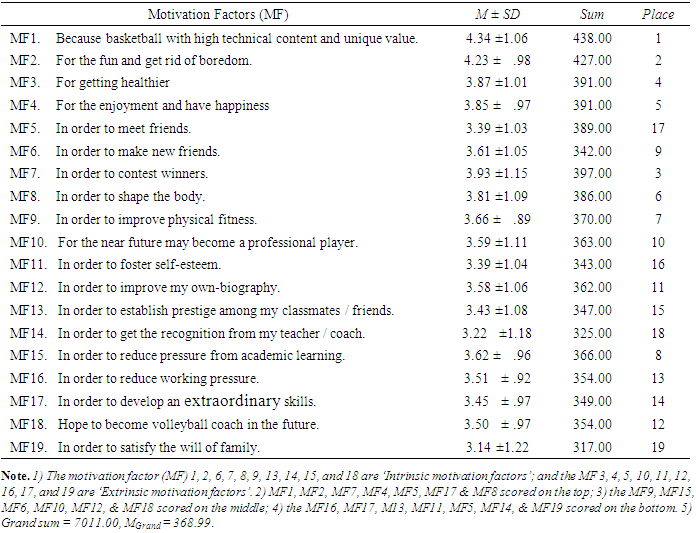

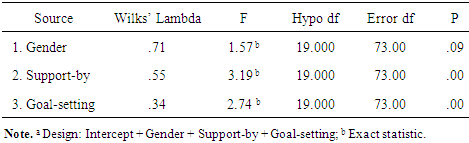

Participation motivations are important for youth basketball players (YBPs) keep engaged in their practices and competitions. This study explored what are the crucial factors that actually motivate YBPs engage in practices and competitions continually. Using data from a sample of 101 YBPs, results indicated that the top six motivation factors (MFs) among total of 19 MFs were: ‘Content and unique-value’, ‘Fun and get rid of boredom’, ‘Contest winners’, ‘For healthier’, ‘Enjoyment and happiness’, ‘Shape body’; while the secondary high impact MFs included: ‘Improve health’, ‘Reduce pressure’, ‘’Make new friends’, ‘Become a professional-player’, ‘To my biography’, and ‘Become a coach”. The MANOVA results revealed: no significant difference in ‘Gender’ aspect, however, significant differences were found in ‘Support-by’ and ‘Goal-setting’ aspects. In conclusion, gender is not the determination aspect; but ‘Support-by’ and ‘Goal-setting’ are. Participants who support-by school possess higher motivations than those support-by parent; set ‘goal for professional’ players possess higher motivation than those set ‘goal for non-professional’ players. Reasons behind of these findings were exhaustively discussed.

Keywords: Youth basketball player, Participation motivation, Practices, Competitions

Cite this paper: Howard Z. Zeng, Wenyan Meng, An Investigation of Youth Basketball Players' Participation Motivations and Relate Elements, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 7 No. 4, 2017, pp. 86-95. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20170704.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction and Background

- Since the second summer Youth Olympic Games (YOG) was held in Nanjing, China in 2014 [1], youth basketball have become one of the hottest sport for the young people who have an sport star dream and that has become an interest research topic in China [2]. However, what reasons/factors that really motivated those youth athletes keep engaged in the sport they love and enable them reaching such high level is rarely covered. For this inquiry, this study want to focus on the youth basketball players' (YBPs) motivations in the city of Nanjing, because since the 2014 Nanjing YOG, youth basketball has obtained much attention from the city and province. The present study aim at: to investigate what are the crucial reasons/factors that actually motivated YBPs engaged in their practices and competitions continually; to use the data collected making exhaustive analyses, so that consequential information and beneficial advices can be provided to their youth sport organization for further improving their youth basketball teaching, coaching and management; to provide suggestions and advices that are suitable for those young athletes; that may facilitate their ‘sport star’ dream become true. According to research literature in youth sports studies, generally speaking, the goal and reasons of youth players engaging in the sports they are: ‘enjoyment’, ‘physical health’, ‘having fun’, ‘foster self-esteem’, ‘friendship’, ‘passion or love the game’, and ‘peer acceptance’, whereas the first three reasons are somewhat similar to those participate motivations in the dominant sports events of Western societies [3-6]. Moreover, Miguel and Machar (2007) and Cohn and Cohn (2016), pointed out that participation motivation supports a successful sport performance; representing one of the most important psychological skills in the game that is playing [7, 8]. Based on the above indicators, we are wondering: whether or not YBPs would be motivated to engage in their practices and competitions as what the literatures have defined? However, one vital problem is: literatures in the youth sports athletes' motivation category shown, research studies involved in participation motivations and relates behaviors for YBPs are extremely limited.

1.1. Purpose and Hypotheses

- Grounded on the above introduction and background, although some of the reasons or factors (as listed above) have known in general; but little is known about what kinds of reasons or factors that actually motivated different types of YBPs who have continually engaged in basketball practices and competitions. The purpose of this study, therefore, is to explore what factors or reasons that truly motivated the YBPs who have playing basketball for years and have reached top level at a remarkable city’s youth basketball league in China. The following specific hypotheses guided the current study: (1) no significant differences would be found on the motivation factors (MFs) between the athletes’ ‘Gender’ (male or female); (2) no significant differences would be found on the MFs between the athletes’ who were ‘Support-by’ (school or parent); 3) no significant differences would be found on the MFs between the athletes’ ‘Goal-setting’ (for professional or for non-professional). Additionally, the eleven related elements on ‘Free Times’, ‘Activities-Engagement’, ‘Practicing Frequency’, ‘Training Condition’, ‘Competition Frequency’ and ‘Financing situation” of the YBPs would also be investigated. The findings from this study would reveal and add a new set of data and first-hand information into the youth athletes study literatures, especially concerning to YBPs’ motivations and related elements can be as a meaningful frame of reference for their future teaching and coaching.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

- A comprehensive theoretical framework named ‘self-determination theory’ (SDT) was employed as the theoretical frame of this study [9]. The SDT is comprised of two major branches: the theory of intrinsic motivation and the theory of extrinsic motivation. Ryan and Deci (2000) indicated that: humans are motivated by three basic psychological needs: competence, relatedness, and autonomy [9]. The competence needs in the SDT model is called effectiveness motivation; the relatedness needs refers to people's need to belong and to feel accepted by others; and the autonomy need, however, refers to people's need to feel self-determined, it is the source of their own action [9]. Similarly, Harter (1981), Pintrich and Schunk (2002) described that organismic needs energize intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, but believe this concept is too general to explain the engagement in specific behaviors, such as engaging in sport competitions [10, 11]. Researchers, therefore, developed a few models that described how motivation triggered by need manifests in intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in specific fields and activities. These models also explained how factors in a specific environment might shape and affect the types of motivation that athletes manifest in different actions or behaviors [10, 11].Furthermore, Breese (1998) illustrated that athletics initial motivation should be defined as intrinsic motivation (participating in sport for enjoyment) or extrinsic motivation (participating in sport to gain rewards) [12]. Breese (1998) continued, athletics initial motivation usually predicts athletes’ attendance and adherence to a particular sport [12]. Such as in our study, a youth basketball player who is intrinsically motivated would be those who go to play or practice his skills every other day for fun; whereas a youth basketball player who is extrinsically motivated would be those who goes to play or practice his basketball skills and strategies to become a better player at the competition so that he/she could win a medal at a competition. It is interesting to know that intrinsic and extrinsic motivation have different effects on an athlete, including whether or not he/she continue on the sport he/she had choose.Similarly, Ryan and his colleagues (1997) explained that individuals who were mainly motivated by competence (engaging in exercise to expand skills) and enjoyment (desire to have fun) could be primarily defined as being motivated intrinsically. In contrast, extrinsically motivated individuals are those behaviors performed in intrinsic motivation aim at to obtain rewards or consequences that are separate from the behavior itself [13]. Breese (1998) further illustrated that when athletes begin participation in a particular sport, they are motivated not only by intrinsic factors but also by extrinsic factors [12]. Some particular sports, however, may be more relying on intrinsic motivation than extrinsic motivation -as described in Ryan and his colleagues (1997) [13]. The reasons are different types of sports need different types of motivation (Breese, 1998). In the current study, we were trying to find out those evidences or the factors that have actually motivated the participants who have engaged in and engaging in the sport of basketball.

2. Methods

2.1. The Sampling

- Sampling for the participants in this study were selected from 10 schools of Nanjing city, in which five were regular high schools have basketball as their traditional sport and five sport-schools based on the record of the division of Jiangsu province sports administration (2015) in the youth basketball category [14]. According to Jiangsu.net (2015), Jiangsu province possesses the following unique features: a) Jiangsu is one of the most developed areas in economy, technology and culture in China; its industries total output is one of the largest in the nation. b) Jiangsu is a center of education and science, possessing the highest density of academic institutions and universities, colleges, and research institutes in China. c) Athletes of Jiangsu province have won more gold medals during the past 10 years than did athletes from any other provinces in China [15]. Remarkably, the city of Nanjing is the capital of Jiangsu provinces just held the second youth Olympics Games not long ago. Nowadays, the youth basketball players have the following way out or futures: a) become a professional player; b) become an elite youth player, earn the credits to go to a good college or university; c) even if not able to become an elite youth player, it still able to go to college or get a decent job, etc.After Nanjing YOG, sports facilities in this city become abundant, even though previously the city of Nanjing was not lack of sports facilities. While youth basketball become one of the hottest sport in Nanjing. Moreover, Populous (2005) described, “Nanjing Sports Park has also demonstrated the significance that Governments are placing on the value of sport and its impact on a community. Sport can help generate goodwill among the population when developing a new city” [16]. This is why we purposefully selected Nanjing as our sampling.

2.2. The Instrumentation

- The Adopted Questionnaire of Youth Basketball Player’s Motivation-Chinese Version (AQBPM-C.V Zeng & Xie, 2015) was employed for data collection [17]. The reasons for using this questionnaire were: a) There is an existing questionnaire with similar purposes, b) to develop a new questionnaire, much more times and funding are needed, c) specialists in basketball motivations and relate behaviors study are available for revising key words from the exist questionnaire to specify uses for youth basketball players and d) research assistants or youth basketball coaches are available for the questionnaire distribution and collection.

2.2.1. Reliability and Validity of the Instrument

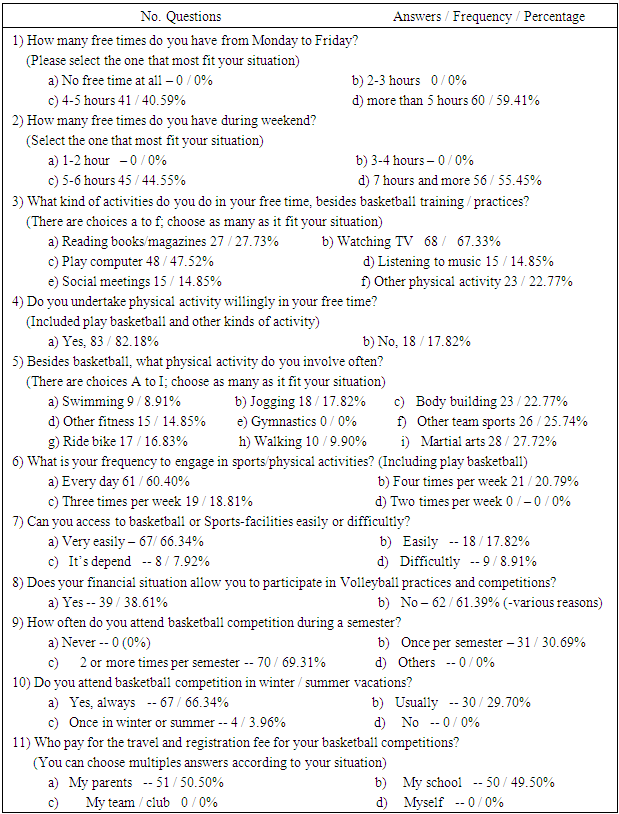

- According to Child (1990), in order to explore the possible underlying factor of the structure for a set of measured variables without imposing any preconceived structure on the outcome, the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is the best solution [17]; therefore, the EFA was executed for the AQBPM-C.V. The results revealed: the analysis extracted 6 factors with perfect correspondence to the 19 items with eigenvalues for the reasons or factors ranging from 2.71 to 8.63 and structure coefficients from .78 to .92 and the majority of the fitted residuals reached the pre set-up significant difference (P < .05) level. Furthermore, the validation process was through a pilot study, reviewing to the content or items. These processes confirmed the following concerns: a) the readability and writing skills of the youth participants (15–17 years old); b) whether or not those youth athletes can truly understand and respond to the questions in the questionnaire correctly; c) it may result in re-wording on some questions or statements to improve the understanding for those youth athletes; d) it may result in cutting or adding numbers of the questions or statements in the questionnaire, and e) whether or not the questions or statements have asked all the possible motivation factors/reasons for the athletes participation in basketball practices and competition.As a result, the AQBPM-C.V. contained three parts: Part I asked ‘General Information’, containing seven questions that covered participant’s general information. Part II asked, “What reasons/factors that truly motivated you engaged in basketball practices and competitions continually?” with 19 motivation factors (MFs) provided. In each MF the participant responds in a 5-points Likert type scale (5-points represents "Strongly agree ", 4-points represents "Agree", 3-points represents "Somewhat-agree", 2-points represents "Little-agree", and 1-point represents "Disagree") [19]. Part III asked 11 relate questions or elements that concern the youth athletes’ ‘Free Times’, ‘Activities-Engagement’, ‘Practicing Frequency’, ‘Training Condition’ ‘Competition Frequency’, and ‘Financing Situations’. For clearer, since these 11 relate questions or elements belong to qualitative data, therefore, the frequency and percentage were utilized to deal with these data. In summary, Part II of the questionnaire contains ten intrinsic motivation factors (items 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15, & 18); and nine extrinsic motivation factors (items 3, 4, 5, 10, 11, 12, 16, 17, & 19). In the other words, it included the three basic psychological needs (competence, relatedness, and autonomy) described by Ryan and Deci (2000) [9]. Part III contains 11 relate elements about the YBPs’ Free Times’, ‘Activities-Engagement’, ‘Practicing Frequency’, ‘Training Condition’ ‘Competition Frequency’, and ‘Financing Situations’ which is qualitative data. All questions and items in AQBPM-C.V. can be found in Table 1 and Table 2.

2.2.2. Data Collection

- The questionnaires were distributed to the YBPs during a planned practice day of their team by the researchers under the supervision of their coaches or administrators. The YBPs were given their rights to participate or not to participate and the ‘confidentiality’ of the survey was well informed. Then, the ‘directions’ about how to respond to the questions and items were illustrated; consequently, 150 YBPs received the AQBPM-C.V., amount of them 101 completed the questionnaire correctly and returned the researchers (Return rate = 67.33%), at this point, the participants also signed the Informed Consent Form. Moreover, an envelope for preventing the participant’s coach from viewing the responds in the questionnaire was offered. The coaches were informed that: After the study accomplishing, they would be provided the overall outcomes of the study.

2.2.3. Research Design and Data Analyze

- The current research design was to look at the effects of three independent variables on 19 dependent variables in the same time; therefore, a 2 x Gender (male or female) x 2 Support-by (school or parent) x 2 Goal-setting (for professional or for non-professional) multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was implemented. The descriptive statistics reflected the general status of how the youth athletes were motivated engaging in basketball practices and competitions; and the 2 x 2 x 2 MANOVA examined whether or not there are significant differences exist among the three independent variables and the 19 dependent variables. Additionally, a follow up MANOVA test would reflect what differences exactly exist among the dependent variables. The statistical program used for the data analyses was IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 22 [20]. And the 11 relate elements about the youth athletes’ training and competition status in the Part III of the questionnaire was to reflect the youth athletes’ ‘Free Times’, ‘Activities-Engagement’, ‘Practicing Frequency’, ‘Training Condition’, ‘Competition Frequency’ and ‘Financing Situations’.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ General Information

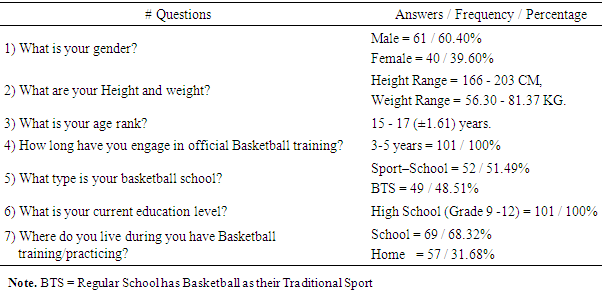

- The following section presents the findings from the current study. It is structured to address the reasons / factors how the participants engaged in the sport of basketball. In total of the 150 questionnaires delivered, 101 were answered correctly and returned (-about 67 percent response/return rate). Data in Table 1 reflected “General Information of the participants”. For example, they were 15 to 17 years old, currently study in high school level (grades 9 to 12); 52 were from Sport–School, and 49 were from regular school has basketball as their traditional sport (simply called ‘BTS’). Moreover, there were 61 boys and 40 girls, and they have been officially engaged in basketball practicing and competitions for 3 to 5 years; their height range was from 166 CM to 203 CM, and weight range was from 56.30 KG to 81.37 KG.

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

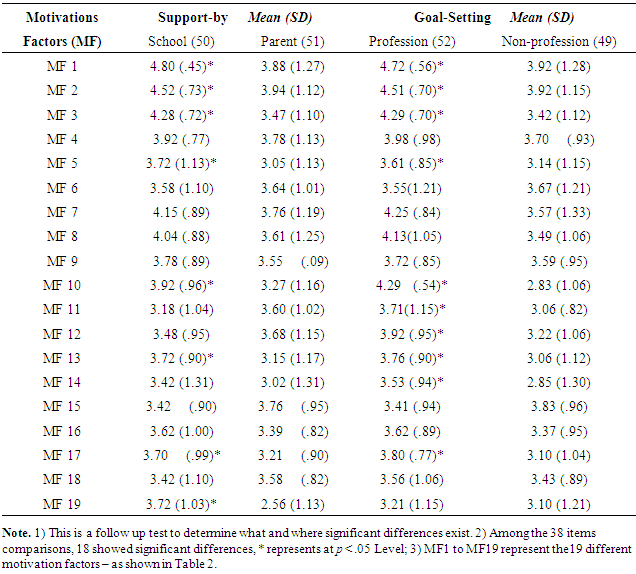

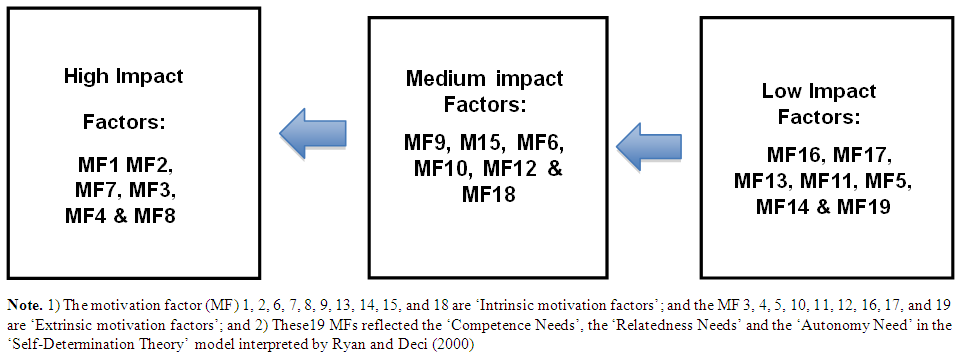

- The current study was designed for: 1) exploring the current status of YBPs’ participation motivations and relate elements in Nanjing, China, and 2) examining if differences exist on the motivation factors among the ‘Gender’, ‘Support-by’, ‘Goal-setting’ aspects of the participants. According to the MFs mean scores presented in Table 2, the placements of the 19 MFs should be divided into three impact groups: a) High impact group, it comprises of MF1 MF2, MF7, MF3, MF4 and MF8; these six MFs possess the highest impact power on this sample YBPs’ motivations. Interestedly, among this group’s MFs, MF1, MF2, MF7 and MF8 are within the ‘Intrinsic motivation factors’ category; other two MF3 and MF4 are in the ‘Extrinsic motivation factors’ category. b) Medium impact group, it comprises of MF9, MF15, MF6, MF10, MF12 and MF18. These MFs possess medium impact power with intermediary scores on this samples YBPs’ motivations. Amazingly, among this group’s MFs, MF9, MF15, MF16 and MF12 are within the ‘Intrinsic motivation factors’ category again; the other two MFs (10 & 12) are in the ‘Extrinsic motivation factors’ category. c) Lower impact group, it includes the rest seven FMs with lower scores. These MFs possess less impact power on this samples’ motivation. Incredibly, among this group’s MFs, MF16, MF17, MF5, MF 11 and MF19 are in the ‘Extrinsic motivation factors’ category; the other two MFs (13 & 14) belong to ‘Intrinsic motivation factors’ category. The motivation features of this sample can be summarized as Fig. 1. (The actual value of each MF can be found in Table 2).

| Figure 1. Three Layers / Groups of Youth Basketball Players’ Motivation Factors |

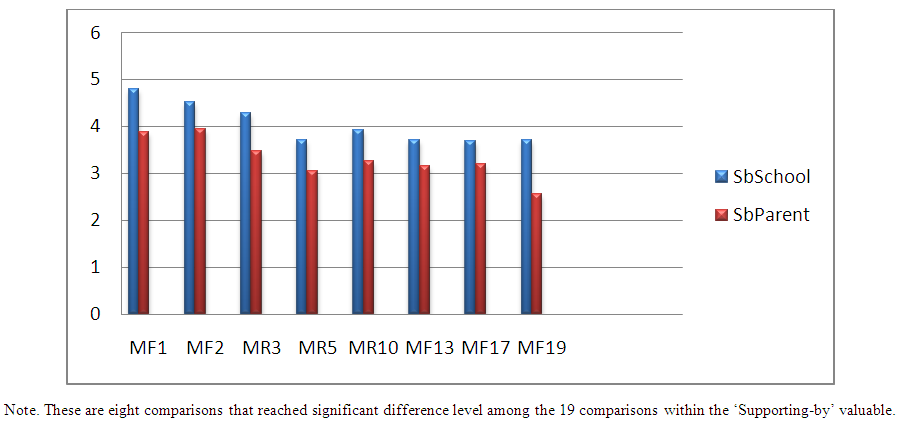

| Chart 1. Comparing the Motivation Scores Reached Significant (p .05) Level in 'Supporting-by' (school or Parent) valuables |

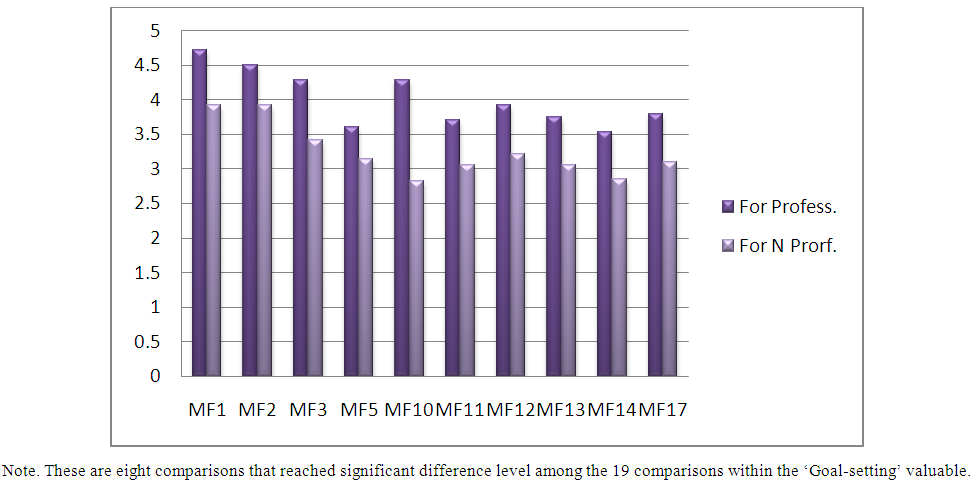

| Chart 2. Comparison the Motivation Scoreat Reached Significant (p .05) level in the 'Goal-Setting' Valuavle |

5. Conclusions

- Based on the above exhaustive discussion, the following three points can be concluded: 1) Both ‘Intrinsic factors’ and ‘Extrinsic factors’ possess comparable impact power on the YBPs’ motivations. 2) The ten ‘Intrinsic factors’ in the AQYBPM-c.v. (Zeng & Xie, 2015) were the core motivation factors, and possess significant higher impact on these YBPs’ participation motivation. 3) Regardless intrinsic motivation or extrinsic motivation, there are some factors or reasons possess higher impact power than the other factors or reasons; meanwhile, there are also some factors or reasons hold less impact power than the others factors or reasons. 4) Gender is not the determination aspect in the players’ participation motivation, but ‘Support-by’ and ‘Goal-setting’ are. 5) The YBPs who support-by school possess higher motivations than those support-by parents; and set ‘goal for professional’ possess higher motivation than those set ‘goal for non-professional’. Youth basketball coaches, trainers, and administers should make exhaustive diagnoses and analyses before implementing these findings to advices and educate their youth players; this should be the right way to improve their coaching, training and management.

5.1. Limitations

- We do realize several limitations exist in the current study. The No.1 is the size of sampling was relatively small. The No. 2 is the data collection scope only covered a City although it is the capital city in a most developed province in China. The No. 3 is basketball coaches from those varsity teams might have some kinds of impacts on their players’ participation motivations, but the “Coach’s influence factor” was not included in the scope of the current study. Lastly, the participants in the current study were selected on purpose. Future study can be improved on the above limitations by including the “Coach’s influence factor” in the research scope (e.g., creating some open-ended questions for coaches to answer); extend data collection to more cities or provinces; and select participants more thoroughly.

5.2. Recommendations and Advices

- The present study explored the YBPs' participation motivations and related elements from Nanjing City, China. The ‘Technical content & unique value’, ‘To develop a Extraordinary skills’, ‘For getting healthier’, ‘For enjoyment and happiness’, ‘To improve my own-biography’, ‘To improve physical fitness’, ‘To make new friends’, ‘To contest winners’, ‘To meet friends’, and ‘To reduce working pressure’ have been identified as the top ten reasons or factors for these YBPs engaged in the sport of basketball. The advices could be provided for the YBPs are: (1) Basketball is a sport that requires different psychological skills; motivations are part of those skills. (2) Higher level of goal-setting motivation was found among professional top players when compared to those less successful players and non-professional players, because Goal-setting motivation, comprehended as a driving force in basketball play, is an essential factor in the development of talented youth players. (3) The core motivations that support YBPs’ initial engage in the sport of basketball are: “Content and unique-value”, “Fun and get rid of boredom”, “To contest winners’, “For healthier”, “Enjoyment and happiness”, “To shape body”, and “To improve playing level”. (4) Less important motivation factors as perceived by the YBPs were: reduce working pressure; satisfying family’s will; establish prestige among friends; being popular and earning rewards. From other perspective, team atmosphere and having a good relationship with coaches also influenced youth athletes’ participation motivations. Moreover, although the values of youth athletes’ participation motivations have been recognized by many youth sports researchers (e.g., Cohn & Cohn, 2016; Miguel & Machar, 2007; Smith, Balagurer & Duda, 2006) [8, 7, & 5]. Further research studies, however, are definitely needed, especially in the area of youth basketball, to further examine what factors of reasons that truly motivated the young athletes taking part in the sport they love, that will enable the sport educators to better cultivate and educate their youth athletes' motivations, even the psychological knowledge and skills; may be that is the better way for nurturing our future sport stars.

References

| [1] | The 2nd summer Youth Olympic Games. (2014). Retrieved from August 18, 2015. https://www.olympic.org/nanjing-2014. |

| [2] | Hurwitz, M. (2016). Why is Basketball so Popular in China? Retrieved from January 3, 2016. https://0x9.me/ZEfzH. |

| [3] | Cox, R.H. (2011). Sport Psychology: Concepts and Application. Brown & Benchmark, Dubuque. |

| [4] | Devine, R., & Lepisto, L. (2005). Analysis of the healthy lifestyle consumer. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 22, 275-283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/07363760510611707 Retrieved from January 18, 2017. |

| [5] | Smith A. L., Balagurer I., & Duda J. L. (2006). Goal orientation profile differences on perceived motivational climate, perceived peer relationships, and motivation-related responses of youth athletes. Journal of Sports Sciences, 24(12), 1315-1327. |

| [6] | Zeng, Z.H., Cynarski, W. J., Baatz, S., & Shawn, P. J. (2015). A study of Taekwondo Students’ Motivation from New York. World Journal of Education; 5(5), 51-63. http://www.sciedupress.com/journal/index.php/wje/article/view/8063. |

| [7] | Miguel, C., & Machar, M. R. (2007). Motivation in tennis, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(11), 769-772. DOI: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.036285. |

| [8] | Cohn, P., & Cohn, L. (2016). How to motivate your young athlete to get better. http://www.active.com/outdoors/articles/how-to-motivate-your-young-athlete-to-get-better. |

| [9] | Ryan, R.M., & Deci, E.L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78. http://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 Retrieved from December 18, 2016. |

| [10] | Harter, S. (1981). A new self-report scale of intrinsic versus extrinsic orientation in the classroom: Motivational and informational components. Developmental Psychology, 17, pp. 300-312. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.17.3.300 Retrieved from January 10, 2016. |

| [11] | Pintrich, P.R., & Schunk, D. (2002). Motivation in education: Theory, research and applications (Second ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. |

| [12] | Breese, H. P. (1998). Participation motivation in ITFNZ Taekwon-Do: A study of the central districts region. Massey University, NZ. |

| [13] | Ryan, R. M., Frederick, C. M., Lepes, D., Rubio, D., & Sheldon, K. S. (1997). Intrinsic motivation and exercise adherence. International Journal of Sports Psychology, 28, 355-354. |

| [14] | Division of Jiangsu province sports administration (2015). http://www.thepacificinstitute.com/success/story/jiangsu-sports-administration Retrieved from December 28, 2015. |

| [15] | Jiangsu.net. (2015). http://www.jiangsu.net/main/ intro/php, 2017. Retrieved from January 3, 2017. |

| [16] | Populous. (2005). A catalyst for urban development and a “People’s Place" for the citizens of Nanjing. Retrieved from September 18, 2016. http://populous.com/project/nanjing-sports-park/. |

| [17] | Zeng, Z. H., & Xie, L. S. (2015). A Study of Youth Tennis Players’ Motivation in Suzhou; Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, Supplement, 86(2), A39-A40. Published online: 27 Jul 2015. |

| [18] | Child, D. (1990). The essentials of factor analysis, second edition. London: Cassel Educational Limited. |

| [19] | Vanek, C. (2004). Likert Scale – What is it? When to Use it? How to Analyze it? https://0x9.me/QBDfx. |

| [20] | BM® SPSS® Statistics V22. (2014). https://0x9.me/t8Olx. |

| [21] | Wikipedia, free encyclopedia. The People’s Republic of China University Student Games. https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Retrieved from January 5, 2017. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML