-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2017; 7(3): 70-78

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20170703.03

Establishment of Psychometric Properties of Pictorial Situational Judgment Test of Values

D. S. Kowal1, Y. K. Nagle2, Nity Sharma3

1Scientist ‘D’ (DRDO), Services Selection Board, Bhopal, India

2Scientist ‘F’ Defence Institute of Psychological Research, DRDO, Delhi, India

3Scientist ‘D’ Defence Institute of Psychological Research, DRDO, Delhi, India

Correspondence to: Nity Sharma, Scientist ‘D’ Defence Institute of Psychological Research, DRDO, Delhi, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Integrity plays a significant role in our society. It can be defined as desirable, trans-situational goals, varying in importance that serves as guiding principles in people’s lives. Traditionally, ‘values’ has been assessed using inventory, retrospective questionnaire and scales. These approaches neglect intra-individual variabilitiy in values and do not capture values as it occurs in real-world settings. The aim of the current study was to provide a method for assessing integrity in day today life that provides both between individual and within-individual information. Pictorial Situational Judgment Test (P-SJT), a semi-projective approach based on critical incidents obtained from subjects and rated by panel of subject matter experts, for assessment of values to recruit potential human capital in Special Forces’ organization. Initially a pool of 120 critical incidents encompassing three domains of values i.e. self-discipline, dutifulness and courage of conviction were collected from male and Finally 75 critical incidents of P-SJT were retained and portrayed into achromatic pictures after being rated by experts on content validity. Four response alternatives were developed for each item. Two best and two worst response alternatives were scored as 1 and 0 respectively. The paper emphasizes the developmental procedure of Pictorial Situational Judgment Test of integrity and would prove to be an aid to the researchers working in this field.

Keywords: Integrity, Special Forces, Pictorial Situational Judgment Test, Critical Incidents

Cite this paper: D. S. Kowal, Y. K. Nagle, Nity Sharma, Establishment of Psychometric Properties of Pictorial Situational Judgment Test of Values, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 7 No. 3, 2017, pp. 70-78. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20170703.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The literature encapsulates Values as desirable, trans-situational goals, varying in importance that serves as guiding principles in people’s lives. Values reflect a specific or converse mode of conduct and end-state of existence. The judgmental elements of individual’s belief of what is good, right, or desirable decide both content and intensity attributes of conduct. Values system is relatively stable, enduring and hierarchical in nature that influences attitudes and behaviour. It starts taking place in early years with inputs from parents, teachers, friends, and significant others in surrounding or remote environment. Values are defined as enduring beliefs that are personally or socially preferable to converse beliefs, which transcend specific situations, and which guide evaluation of behaviour (Rokeach, 1973). The main features of the conception of values can be summarized from the writings of many theorists and researchers as (a) Values are beliefs, but they are beliefs tied inextricably to emotion, not objective, cold ideas; (b) they are motivational construct and refer to the desirable goals people strive to attain, (c) they transcend specific actions and situations and are abstract goals. The abstract nature of values distinguishes them from concepts like norms and attitudes, which usually refer to specific actions, objects, or situations, (d) they guide the selection or evaluation of actions, policies, people and events. That is, values serve as standards or criteria, and, (e) they are ordered by importance relative to one another. People’s values form an ordered system of value priorities that characterizes them as individuals. This hierarchical feature of values also distinguishes them from norms and attitudes.Difference in the relative and hierarchical significance placed on the values means that they embrace potential for conflict within and between individuals and organizations. The values construct is widely evoked in organizational literature, but tends to be compromised by slack conceptualization so that the progress of values research continues to be constrained by the lack of a common theoretical basis (Connor & Becker, 1994; Stackman, Pinder & Connor, 2000). At the same time, organizational values are increasingly being used in practice to stimulate, and enforce, the alignment of behaviours (Quappe, Samso-Aparici & Warshaesky, 2007), emphasizing a form of normative control that raises a number of issues around effectiveness and ethics. This paper contributes to the substantial insight encompassing Special Forces organizational values by exploring distinct domains of values and development of test to assess them. The significance of organizational values is underlined by their central place in many organizational phenomena including identity (Ashforth & Mael, 1989), culture (Schein, 1985), person-organization fit (Cable & Edwards, 2004) and socialization (Dose, 1997). Conformity with organizational values is offered as an alternative to bureaucratic functional activities such as service productivity (Dobni, Ritchi, & Zerbe, 2000). Organizational values are shown to influence the interpretation of strategic issues (Bansal, 2003), strategic choice (Pant & Lachman, 1998), strategic change (Carlisle & Baden-Fuller, 2004) and management decision-making (Liedtka, 1989), while Hambrick and Mason’s (1984) ‘upper-echelons’ theory is based on the link between organizational outcomes and managerial values. Organizational values also shape the ethical stance of an organization (Finegan & Theriault, 1997), employee commitment (Ostroff, Shin, & Kinicki, 2005) and relationship with external constituents (Voss, Cable, & Voss, 2000). In short, values have a long reach and a wide span of influence based on critical incidences and characteristics in organizations.Critical incident (CI) is defined as any incident which led to an action that contributed to an effective outcome (helped to solve a problem or resolve a situation) or resulted in an ineffective outcome (it partially resolved a problem, but created new problems or needs for further action). The critical incident technique involves collection of brief, written, factual reports of actions in response to explicit situations or problems in defined fields. Incident reports may be written by participants who took actions, by qualified observers, or both. Dr. Flanagan (1954) and several wartime colleagues, first described this critical incident technique as a set of procedures for collecting direct observations of human behaviour in such a way that facilitates their potential usefulness in solving practical problems, and thereby to develop broad psychological principles. Situational Judgment Tests (SJTs) are assessment techniues designed to measure judgment in work settings and used to assess a variety of constructs (McDaniel et al., 2001; McDaniel & Nguyen, 2001; Weekley & Ployhart, 2006) and have been extensively researched for their utility in personnel selection (McDaniel et al., 2001). SJT presents the respondent with a situation and then evaluates among several response alternatives to the situation, which predict how well an individual performs on a job (Motowidlo et al., 1997). Evaluation of SJTs response alternatives by an individual reflects behavioural consistency (Motowidlo et al., 1990; Motowidlo, Hooper, & Jackson, 2006). Meta-analytic summaries of research have documented that SJTs have useful levels of validity as predictors of job performance (McDaniel et al., 2001; Mcdaniel & Whetzel, 2007). The implicit trait policy given by Motowidlo et al. (2006) describes that there are inherent beliefs about casual relationships between personality traits and behavioural effectiveness. Thus there are individual differences in the selection of response alternatives which are related to the personality trait of the individual. SJTs were developed in various formats such as paper-and –pencil tests with written description of situations (Chan & Schmitt,2002), computerized multimedia scenarios (McHenry & Schmitt, 1994; Olson-Buchanan et al., 1998; Weekley & Jones, 1997), computer-based videos (Chan & Schmitt, 1997; Weekley & Jones, 1997), and pictorial with both written and pictorial description of situations (Sharma & Nagle, 2015). The covert personality characteristic of the test taker gets projected as the test-takers are able to identify with character and situation as it increases the comprehensibility of the test items manifold. The same has been found in the studies carried out on Pictorial Situational Judgement Test of Personality (Nagle et al., 2017).Situational judgment test items can be divided into stem and responses. The item stem is the portion of the item which presents the situation to the respondent. The responses consist of a list of possible response alternatives to the situations that are presented to the respondent for their evaluation. Both the item stems and the item responses can be categorized in a variety of ways. The item stems can vary in their fidelity (Motowidlo et al., 1990), length (Wagner & Sternberg, 1991), complexity, comprehensibility (Sacco, Schell, Ryan, Schmitt, Schmidt & Rogg, 2000) and present an overall situation followed by subordinate situations. Item responses do not tend to vary much across SJTs. Some SJTs propose solutions to problems, to which respondents rate their agreement (Chan & Schmitt, 2002). Others offer multiple solutions from which respondents choose the best and/or worst alternatives (Motowidlo et al., 1990; Olson-Buchanan et al. 1998). Accordingly, there are two types of response instructions for SJTs – knowledge instructions and behavioural tendency instructions. Knowledge instructions ask respondents to display their knowledge of the effectiveness of behavioural response. The respondent is asked to display their knowledge about the effectiveness of the response alternatives by marking either the best or the worst response option or by rating the response options. Behavioural tendency instructions ask respondent to report how they typically respond by asking them, “What would you do? / What would you most likely do? or, rate each response on likelihood that you would do the behaviour”.

2. Development of Pictorial SJT

- The Pictorial Situational Judgment Test (P-SJT) was developed comprising of three phases. The first phase devoted to identification of constructs and initial item development. Second phase involved selection of items for final form based on panel of expert’s ratings, development of pictorial form of situations and development of scoring key. Administration of test on a sample of undergraduates was conducted in third phase.

2.1. Phase I

- An extensive job analysis was carried out from both research and practice perspectives to explore dynamic nature of Special Forces’ organizational values. As a result, three constructs of values were emerged viz Self-Discipline, Dutifulness, and Courage of Conviction. These behavioural constructs were operationally defined. Both inductive and deductive approach was followed for item construction. Inductive approach was followed in discussions and brainstorming sessions by sixteen subject matter experts (psychologists, and academicians). Deductive approach was followed in collecting critical incidents from target populations of 200 college going students (100 male and 100 female) with age range of 17-21 years, for each construct of value. The target population of 200 participants were from various academic institutions, colleges and Universities of India was provided a questionnaire comprising of demographic, academic and age details. The questionnaire consisted descriptions of each behavioural characteristics of three domains of value- Self-Discipline, Dutifulness, and Courage of Conviction. The participants were asked to write responses in three steps, firstly to write a situation faced either by you or someone known to you who are related to the description of “behaviour characteristics”. Secondly write how you or someone known to you successfully handled the situation and thirdly write down alternative ways of handling the same situation which is reasonable but not optimal, other than the one written above by you. Themes were generated from these critical incidents which were clustered under respective constructs after editing and excluding content of the situation which raises legal concerns. These themes were taken into consideration for development of the item stem of SJT. The main and alternative multiple responses given by the subjects were used to develop the response alternatives for each stem. Four response alternatives were developed for each stem. Initially for males, 123 item stems were developed distributed as 40 item stems of self-discipline, 51 item stems of dutifulness, and 32 item stems of courage of conviction. Primarily six potential response alternative of each 123 item stems explicitly 738 item response alternatives were also developed distributed as 240 item response alternatives of self-discipline, 306 item response alternatives of dutifulness, and 192 item response alternatives of courage of conviction. For females, 68 item stems were developed distributed as 24 item stems of self-discipline, 20 item stems for dutifulness and 24 item stems for courage of conviction. Primarily six potential response alternative of each 68 item stems explicitly 408 item response alternatives were also developed distributed as 144 item response alternatives of self-discipline, 120 item response alternatives of dutifulness, and 144 item response alternatives of courage of conviction (Kowal and Nagle, 2016).

2.2. Phase II

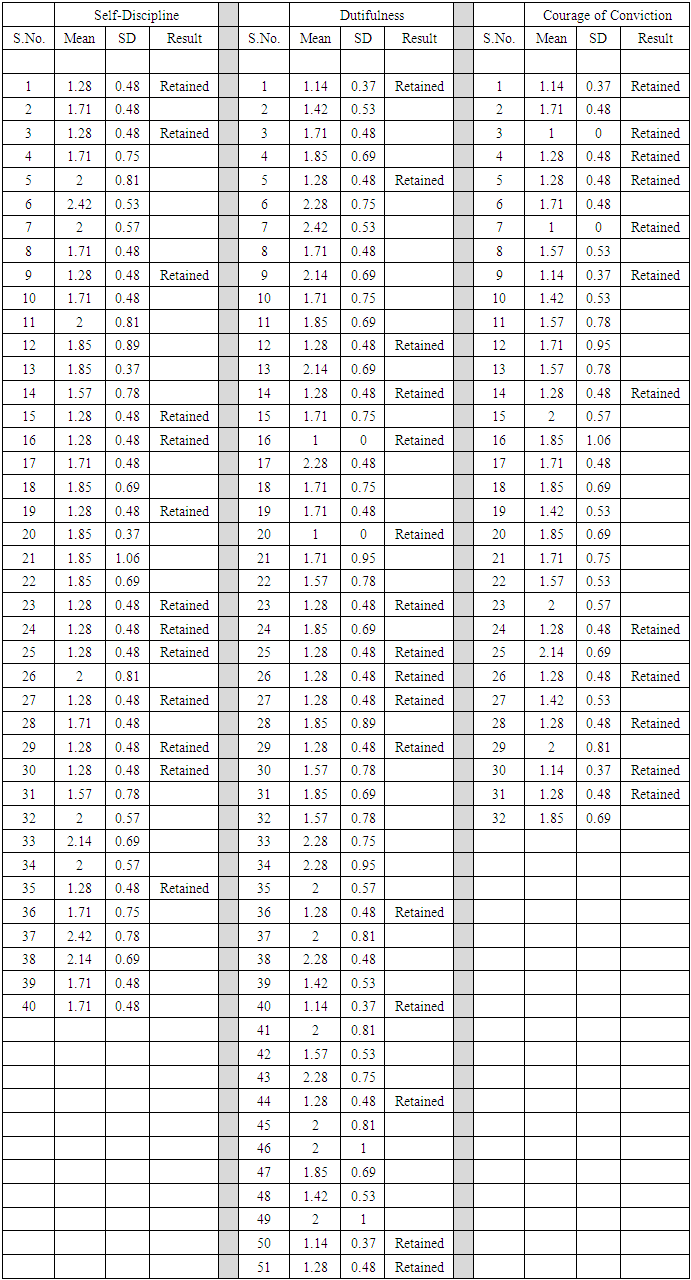

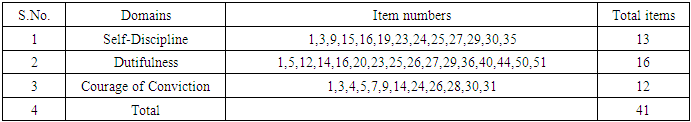

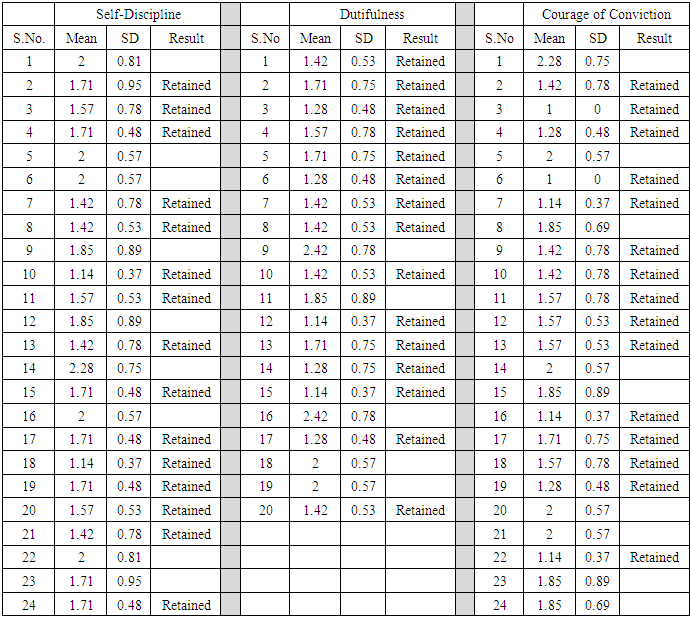

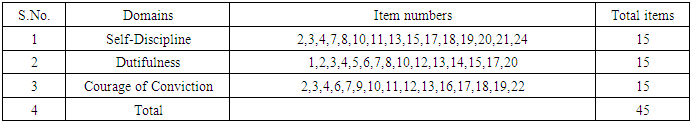

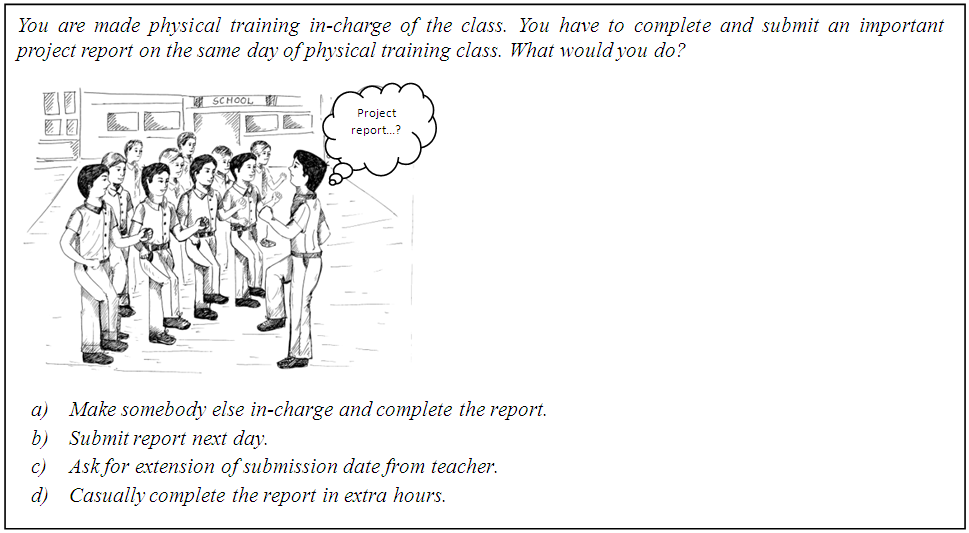

- Second phase of the study comprises of selection of item stems, response alternatives for final form, development of pictorial form of item stems and development of scoring keys. Only 123 Item stems were given to a first panel of seven subject matter experts (SMEs) including scientists, practicing and amateur psychologists. The concordance of the situation with operational definition of construct and intensity of response alternatives were ensured. The criterion for final selection of items was 58% agreement among the panel of experts. The mean scores of the ratings on three point scale as 1- high, 2- moderate, and 3- low, by panel of experts were determined. Mean value 1 was perfect high, 2 was 50% and 3 was perfect low, thus the items with a mean < 1.40 (85%) were retained (Table 1). Hence, out of 123 item stems 41 were retained in the final form of test (Table 2). After this 41 retained item stems along with item response alternatives were presented to the same panel of SMEs to award the intensities to four item response alternatives of each item stems and discarding the other two response alternatives. The average intensities were calculated for all the SMEs. Two best and two worst item response alternatives were decided for each item stem. After this, 41 retained item stems were portrayed into achromatic pictures by a commercial artist in close interaction with the researcher. A dialogue box was also included in the pictures to help the subjects identify the focal figure and to trigger the response based on it (Figure 1), which induced clarity to the thought process of the subject to specific construct (Sharma et al., 2015). These 41 retained item stems along with pictorial form were presented to the second panel of SMEs to rate how well a picture depicts the item stem on a three point scale. The criterion for final selection of picture was 75% agreement among the panel of experts. Observations made by them were incorporated and accordingly nine pictures were modified and six pictures were re-portrayed. Same procedures were followed for female P-SJTs. For female, the item stems with a mean ≤ 1.71 (64.9%) were retained (Table 3). Thus out of 68 item stems, 45 item stems were retained in the final form of test (Table 4). The criterion mean score for female was decided lower than male mean score because of the limited variety and repetitive themes have emerged in critical incidents written by female sample. Four item response alternatives were scored as two best and two worst, and item stems portrayed into pictorial form. The criterion for final selection of female pictures was again 75% agreement among the second panel of experts. Observations made by them were incorporated and accordingly eleven pictures were modified and two pictures were re-portrayed.

| Figure 1. Example of pictorial SJT item for Male |

|

|

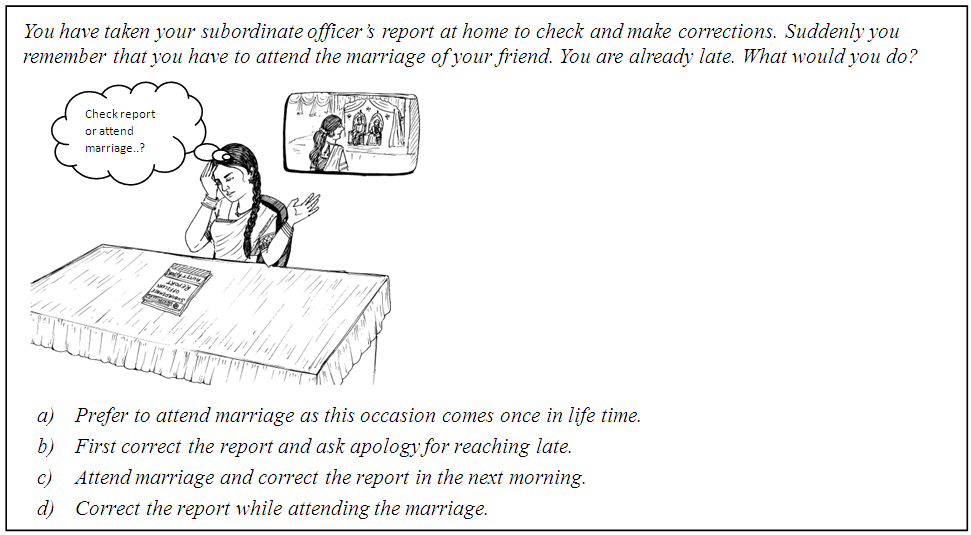

| Figure 2. Example of pictorial SJT item for Female |

|

|

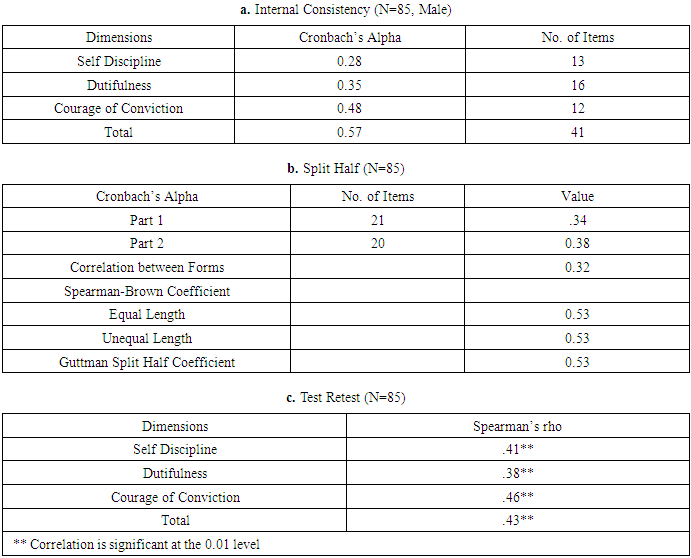

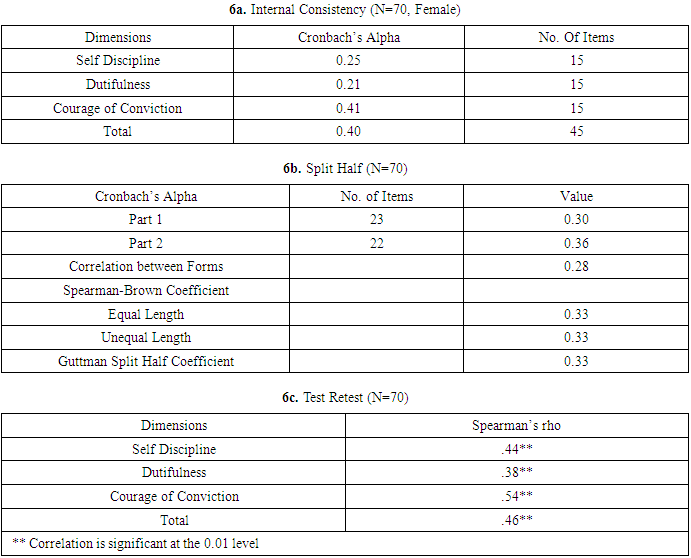

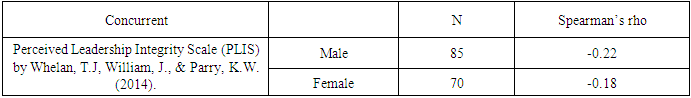

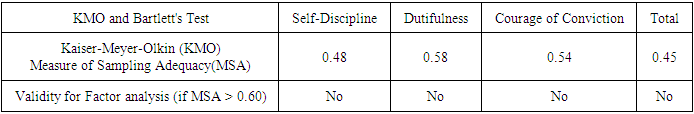

2.3. Phase III

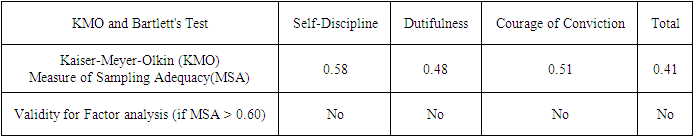

|

|

|

|

|

3. Conclusions

- The existence of situational judgment tests have been since more than decades, here an attempt was made to develop semi-projective method for assessment of ‘values’ based on P-SJT. The constructs and domains of value were derived through job analyses by identifying competencies needed for the Special Forces. The data was collected on indigenously designed questionnaire based on critical incident technique. The academicians, practitioners, researchers had formed the panel of experts so as to maximize the item characteristics influencing validity and minimizing item characteristics influencing adverse impact. Finally 86 items, 45 for male and 41 for female were developed and would be tried out on a sample to find out the feasibility of computer aided methods.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML