-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2017; 7(3): 60-69

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20170703.02

Towards Mental Health with Child Social Competence and Parental Disciplinary Approaches in Egypt

Huda Assem Mohammed Khalifa

Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Huda Assem Mohammed Khalifa, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The purpose of this research is to investigate the impact of socio-demographic predictors (age, gender, family monthly income, number of dependents under 18 years, parental marital status, and parental education level) on children’s social competence through three dimensions: (1) I don’t pay attention to my children, (2) I have to repeatedly reteach skills to my child, and (3) The child withdrew socially because of abuse. The research is based on a survey taken on a sample of 1751 children of 10–16 years of age across Assiut governorate during May 2016. The findings show that these three dimensions do have a significant influence on a child’s social competence, and that the predictors of age, gender, family monthly income, parental marital status, and parental education level affect the incidence of social competence (social adaptability) via each of these three dimensions. The number of dependents under 18 years of age in a family has no effect on a child’s social competence. Based on these three dimensions the research also shows that children in Egyptian families display greater social competence with increasing age, with higher family monthly income, with higher parental educational levels, if they are female, and if their parents are married.

Keywords: Social competence, Parental Discipline, Egypt, Child adaptiveness

Cite this paper: Huda Assem Mohammed Khalifa, Towards Mental Health with Child Social Competence and Parental Disciplinary Approaches in Egypt, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 7 No. 3, 2017, pp. 60-69. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20170703.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Social competence (social adaptiveness) in children refers to how well they can interact with their peers, teachers and family members. Can the chid keep disruptive emotions and impulses in hand, or use socially appropriate behaviour, or establish and then maintain high quality and mutually satisfactory personal relationships? Can the child avoid negative treatment from others? How a child perceives his or her ability to communicate with others, along with parental or teacher assessment of their social competence can have short or long-term positive or negative impacts on their social skills. Social skills are vital for children so that their emotional and social needs can be satisfied. Our previous research has shown that many parents in Middle Eastern countries use harsher disciplinary approaches than what is commonly used nowadays in the West. The three categories of parental discipline we use as constructs of social competence are derived from the findings of that research. We found that the parents we researched tended to believe in “Spare the rod and spoil the child” and resorted to physical discipline for any child misconduct. As is traditional, they did not take notice of what their children had to say about the situation/misconduct, but commonly just responded physically. Typically, they were not prone to continually reteach their children about why/how to avoid broaches of the ‘rules’ but again, just responded physically. Some of the physical discipline used was indeed very harsh. The purpose of this paper is to show how the development of social competence relates to conditions like this that Muslim and Arab children may find themselves in. Within this context we have set out to investigate the construction of social competence for such children as it relates to: (1) I don’t pay attention to my children, (“Pay attention”), (2) I have to repeatedly reteach skills to my child (“Reteach skills”), and (3) The child withdrew socially because of abuse (“Child withdrew”). Our research also investigates how socio-demographic variables like age, gender, number of dependents in the family, parental marital status, parental educational level, family monthly income, and residence affect social competence.

2. Literature Review

- Mother-child relationshipChildren’s perception of their social acceptance and social competence can be determined by the quality of the bond created by mother and child. Kulkofsky, Behrens, and Battin (2015) observed that the mother’s support of the child’s autonomy and self-confidence (observed in the mother’s conversation) was directly related to the child’s perception of its social acceptance. They observed, too, a relationship between mother-child conversation and the child’s perception of its social competence. Junttila and Vauras (2014) studied how parental evaluations of their ability to rear their child influenced the child’s school-related social competence. It was hypothesized that mothers with more positive self-evaluations (i.e. higher scores on a parental self-efficacy measure) would produce children with stronger reading and arithmetic skills along with higher non-verbal intelligence compared to the children of parents with lower parental self-efficacy self-evaluations. The children of fathers with positive self-efficacy scored high in reading and arithmetic skills. The children both of whose parents scored high on the parenting self-efficacy scale exhibited greater cognitive skills than other children. Pasiak and Menna (2015) studied 59 mother-child dyads with three to six-year-old aggressive and non-aggressive children. It was observed that, among non-aggressive children, there was more interactional synchrony in a free play task. Moreover, mother-child dyads with non-aggressive children were more likely to interact flexibly and freely during both free play and structured block tasks than mother-child dyads with aggressive children. This study is consistent with the social learning theory that children emulate the behavioural patterns of their parents, so harsh parenting will give rise to antisocial elements in children. The role of mother’s support in combatting children’s behavioural reservations is significant today especially, for example, in a growing competitive market-oriented Chinese society where self-confidence is increasingly being emphasized. In this context, Chen, et al (2014) conducted a study on 286 Chinese 2-year-old toddlers with equal numbers of both genders. It was concluded that behavioural inhibitions were negatively associated with social competence and positively associated with shyness if children experience a low level of maternal support. If mothers provided a high level of support to their children, on the other hand. It is suggested that parents should adopt a responsive parenting style (i.e. interact with their children rather than ignore them) to prevent their children developing low social competence born out of inhibitions. Song and Wang (2013) studied mother-child reminiscences of the child’s early experiences with peers and its relation to the child’s perception of social competence. It was seen that the mothers’ supportive interactions helped their children make valid statements, and later on, engage in discussions to help them develop peer relationships based on peer evaluation. On the other hand, though, the study revealed that children who reminisced specifically about negative peer experiences in the past tended to score high on social competence, and this was attributed to their better understanding of peer relationships that developed as a result of those reminiscences. Wang and Dix (2015) found that maternal depression in the early years of a child’s life, i.e. from 6 to 36 months, could result in low social competence and social adjustment. Three reasons were posited for this: depressed mothers have a poor perception of their children’s behaviour; given their stress levels, depressed mothers have a low tolerance level for children’s misbehaviour, and depressed mothers’ depression and anxiety worsen their sensitivity to their children’s negative behaviour (Hartas, 2011). According to Chan (2010), mothers who adopted a strict parenting style had a greater tendency to positively react to their children’s emotions than lenient mothers, and this, in turn, could have developed the construction of emotion-coping strategies in children.Family, parents and peer influenceA child’s temperament can moderate the impact of family conflicts on its social competence. Based on a study conducted on Chinese urban nursery school children, Zhang (2015) saw that children with difficult temperaments were more negatively influenced by physical conflict in families than children with easy temperaments. Moreover, difficult children exhibited reduced internalization of problems and increased social competence when reared in families with fewer physical but more verbal conflicts, while easy children did not benefit like this from either of these families. This is in line with another study (Kouros, Cummings, and Davies, 2010) which found that parental conflict was positively correlated with externalizing behavior in children. Parental conflict also predicted low social competence during preadolescence. Hence, it can be concluded that the negative impacts of interparental conflicts are not limited to the development of short term social competence. Attachment security with parents can have a positive impact on social competence in children (Verissimo, Santos, and Fernandes, 2014). They studied 147 preschool children and observed that high attachment security with parents could develop social, emotional and cognitive skills in children which in turn made them acceptable by their peers. In another study, Feldman, Bamberger and Kanat-Maymon (2013) found that parent-child interactions during early childhood could positively influence social competence and reduce aggression in preschool years.Psychologically or physically disabled childrenCuzzocrea, F., Larcan, R., Costa, S., & Gazzano, C. (2014) studied relational experiences of siblings of disabled (low intellectual ability) and non-disabled children. It was seen that siblings of disabled children had more difficulty in interacting with peers of the opposite gender and teachers than siblings of non-disabled children. Moreover, those children exhibited aggressiveness especially if they had a poor relationship with their fathers, and also suffered from anxiety or depression if they shared a poor relationship with their mothers. In a meta-analysis of articles about children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Whalon, K. J., Conroy, M. A., Martinez, J. R., & Werch, B. L (2015) found moderate to high positive impacts of peer-mediated interventions, adult-mediated interventions and child-specific interventions. This means ASD children can become more socially compatible with peers in school with the help of specific social skill interventions. In a similar context, Vickerstaff, S., Heriot, S., Wong, M., Lopes, A., & Dossetor, D. (2006). concluded that both the parental perception of social competence of ASD children and ASD children’s own self-perception of social competence are dependent on their intellect. ASD children with higher intellectual ability also perceive themselves as less socially competent than those with lower intelligence. Yagmurlu and Yavuz (2015) studied children with chronic orthopaedic disabilities. It was seen that the children with a high level of focus were more attuned to peer emotions and thereby developed stronger social competence compared to those with a lower level of focus. The results also showed gender as a variable factor, as girls with orthopaedic disabilities were more socially competent than similar boys. However, in this case, maternal warmth and degree of disability did not affect social competence. Another study (Phillips and Hogan, 2015) was conducted on preschool children with hearing, vision or physical disabilities. It was seen that these children were equally inclined to participate in social activities as non-disabled children, but had lower social competence than non-disabled children.Social competence in schoolsHumphries, Keenan and Wakschlag (2012) observed a positive correlation between social competence and school performance in a sample of 80 African American children 3-6 years of age. Moreover, teacher perception of high social competence in the children synchronized with the children who behaved with their teachers and peers in a socially compatible manner. Nelson, J. A., Leerkes, E. M., Perry, N. B., O'Brien, M., Calkins, S. D. and Marcovitch, S. (2013) studied the relationship between mothers’ parenting and children’s negative emotions and school performances. This was based on the fact that the emotional support of mothers could help children to improve academic performance. It was found that European-American mothers had a problem-focused approach help children to dispel their negative emotions, but this same strategy did not work for African-American children. According to Barbarin, O., Bryant, D., McCandies, T., Burchinal, M., Early, D., Clifford, R., Howes, C.et al. (2006), the negative impacts of low social and emotional competence in preschool were reflected in social skills and behavioural patterns in grade school, and such negative impacts could have long term effects on academic skills and social competence. Furthermore, Fantuzzo, J. Bulotsky, R., McDermott, P., Mosca, S., Megan Noone, M., L., et al. (2003) observed that low social skills in young children could result in a lack of peer-related social skills in later years. Gender as a variable factor in social skills in both state and private preschool children was studied by Altay and Gure (2012) who concluded that girls had more positive interactions with peers and teachers, while boys had more negative interactions with peers and teachers. This was also reflected in the social skill ratings of children given by teachers and parents. It was also revealed that harsh parenting could lead to low social competence in children, whereas warm parenting could lead to higher social competence in children. Private preschool children exhibited lower peer-related social competence than their counterparts in state preschools. The influence of group activities on social competence in preschool children has been studied by Daniel, J. R., Santos, A. J., Peceguina, I., & Vaughn, B. E. (2015) who investigated 242 Portuguese preschool children from middle-income families. It was seen that children belonging to a unified subgroup tended to exhibit more positive social skills than children belonging to a less unified subgroup. This is however questioned by Carman and Chapparo (2012) who studied 10 children of 8-12 years of age and observed high social skills in children one-to-one rather than as members of a group. Bohn-Gettler, C. M., Pellegrini, A. D., Dupuis, D., Hickey, M., Hou, Y., Roseth, C., & Solberg, D. (2010) also observed that the greater physically activity of boys tended to develop into more competitive and controlling approaches in their social interactions than was the case for girls. The influence of paternal support on social competence of preschool children was studied by Torres, N., Veríssimo, M., Monteiro, L., Ribeiro, O., & Santos, A. J. (2014) who concluded that children with fathers participating in leisure activities scored high on social competence and low on externalizing problems, and that this pattern was more discernible in boys than girls.Variable factorsRace can be a moderating factor on children’s social competence and the teacher-child association. In this context, Garner and Mahatmya (2015) studied 132 Black, White and Latino pre-schoolers. It was seen that low-income children had difficulty in emotional management and that low-income mothers had difficulty in understanding children’s emotions, a situation which was attributed to their own stress. Another result was that high-income children had a high capacity for emotional regulation and had positive relations with teachers. Latino children, on the other hand, had more conflict-ridden relations with teachers than Black children. In another racial study of Zimbabwean adolescents (Mpofu and Thomas, 2006), both black, white and of both genders, attending multiracial schools, it was concluded that self-concept and social competence were uncorrelated for both blacks and whites. This study established a low but positive correlation between self-esteem and social competence in adolescents. Genetic influence is another factor of social competence and was studied by Van Ryzin, M. J., Leve, L. D., Neiderhiser, J. M., Shaw, D. S., Natsuaki, M. N., & Reiss, D. (2015) who observed that children with highly responsive parents displayed more social competence than children whose parents were less responsive. It was concluded that positive parents can offset the negative influences of social vulnerabilities on social competence. Obesity as factor in the development of social competence was studied by Jackson and Cunningham (2015) who noted that obese children were inclined to exhibit poor social skills. It was concluded that poor social competence could lead to a subsequent increase in body weight, but that obesity was not a contributing factor to low social skills. The explanation for this was that children chose unhealthy behaviour to avoid the stress that flowed from their pre-existing social incompetence and negative social responses.HypothesesThree hypotheses are being investigated in this paper:1. That “I don’t pay attention to my children” (“Pay attention”), is a variable that constructs social competence.2. That “I have to repeatedly reteach skills to my child” (“Reteach skills”) is a variable that constructs social competence.3. That “The child withdrew socially because of abuse” (“Child withdrew”) is a variable that constructs social competence. On the face of it, the first two of these three hypotheses relate to the parental discipline approach rather than the child’s social competence. However, they reveal parental orientation toward a child at times of conflict, and at those times, that orientation is critical to the construct. The paper also investigates the relation of these three variables to various independent socio-demographic variables (age, gender, residence, parental marital status, parental educational level, monthly income of family, and number of children in family less than 18 years old).

3. Methodology

- The research takes a positivist approach since the analysis is quantitative in nature. It considers a sample of 1450 children 10–16 years of age across Governorates in Egypt. A 23-item questionnaire was distributed to all children (male and female) in a randomly selected sample and was answered during face-to-face interactions. Both open ended and close ended questions were used. The quantitative method included exploratory and confirmatory analysis. Most of the items are structured as per the Likert scale of 1 to 5. Amos software was used for the statistical analysis. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) with path diagram models was used, and, the goodness of fit tests were estimated for the SEM. ParticipantsThe research is based on a survey of 1751 children from a sample of 1751 male and female children of 10–16 years of age across Assiut governorate during May 2016.Instrument: Reliability, Validity and Factor ExtractionThe reliability of the questionnaire was measured by KMO, Bartlett’s test. Child social competence as a construct of the following observed dimensions was tested: (1) I don’t pay attention to my children, (2) I have to repeatedly reteach skills to my child, and (3) The child withdrew socially because of abuse. First of all, the suitability of a factor analysis was tested via KMO, Bartlett’s test. The closer the values of the KMO test to 1, the better. The result obtained of 0.518 showed moderate suitability. The sphericity assumption held since Bartlett’s test is significant at the 5% level, and consequently, the factor analysis could continue. The communalities it is evident that child reward and “Reteach skills” had low shared variance. The remaining variables had moderate levels of shared variance. The extracted factors, “Pay attention”, “Reteach skills” and “Child withdrew” were thus seen to be associated with the socio-demographic variables included in the dimension. The criterion for extraction was an Eigenvalue higher than 1. Predictive factorsTesting for a predictor (i.e. independent variable) which could statistically and significantly influence the dependent variable ‘social competence’ was important to begin with. This involved two steps. Firstly, the dependent variable was extracted and evaluated according to its three determinant variables using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), the three being: (1) I don’t pay attention to my children, (2) I have to repeatedly reteach skills to my child, and (3) The child withdrew socially because of abuse. These were grouped into two factors: Secondly, a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis was carried out for the dependent variable (social competence) to illustrate its association with the various independent socio-demographic variables of age, gender, residence, parental marital status, parental educational level, monthly income of family, and number of children in family less than 18 years old (“Children”).

4. Findings

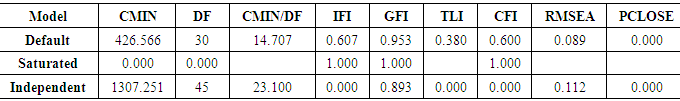

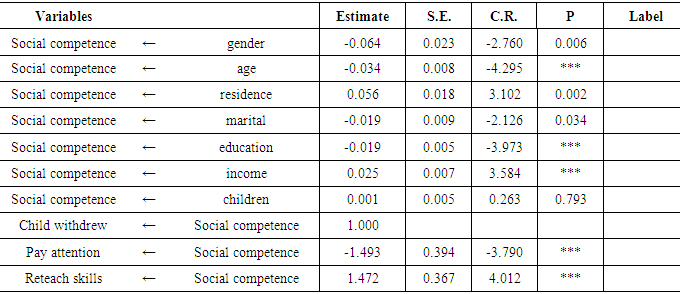

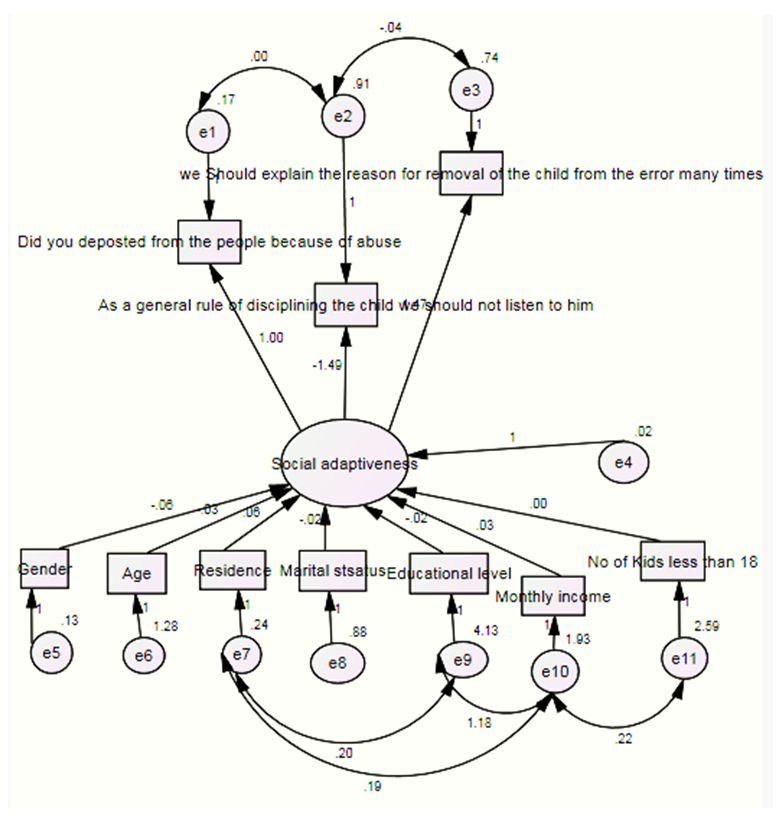

- The results obtained by CFA in Amos for the three hypotheses are presented below in Table 1’s path diagram and SEM.The summary of the model fit values in Table 1 shows that there is a good fit because the PCLOSE values are less than both 0.05 and 0.01 which means that the model is significant at 5% and 1% levels of significance. As well, the value of chi-square/df (CMIN/DF) is more than 10 and GFI is moderately high (almost 1). The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) analyzes the issues between a hypothesized and null model without considering sample size. For a good fit, the model RMSEA should be equal to or below 0.08. This model does not meet that requirement. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) illustrates the ratio of difference between χ2–df of the null and the hypothesized model to χ2–df of the null model. To be acceptable, the model should have a CFI measure of 0.9, so with a value of 0.6, the model does not satisfactorily meet this requirement. However, based on the other values we may conclude that the model is valid and reliable.

|

|

| Figure 1. Path diagram for the three dimensions and their relationship with the socio-demographic variables |

5. Discussion

- Social competence in children is manifested in their behavioural patterns and communication skills. As social competence is a yardstick for the proper emotional growth of young children and adolescents, it is reflected in their interactional skills not with only peers but also with family and teachers. How a child perceives his or her own communication skills and group participation skills affects his or her level of social competence. Any child, though, can exhibit different kinds of traits such as mood fluctuations, empathy toward others, loneliness, responsiveness or non-responsiveness, enjoyment of the company of peers, attention seeking, friendliness, and feelings of neglect by or respect from others. Accordingly, teachers and parents should adopt appropriate strategies for each of these traits and the degree to which each child has them, so as to encourage the development of social competence in children and further facilitated by their gender, age, family status, parental education level and socio-economic status. This current study has studied the different factors that contribute to the development or under-development of interactional and communication skills in children, which contribute to their social competence in relation to peers, teachers and family members. It has also established that the gender of a child is statistically significantly associated with social competence at a 5% level of significance (as evident in the p-values). This is supported by earlier studies that found differential social adroitness in boys and girls at preschool level. Walker, Irving and Berthelsen (2002), for instance, found that girls were more socially responsive than boys with their peers and that girls exhibited less physical aggressiveness than boys. In addition, they found that the social behaviour of boys and girls differed depending on whether they were with same or opposite gendered peers: both genders behaved less aggressively when dealing with same gendered peers than opposite gendered peers. This tendency to behave more competently in same gender dyads has also been supported by Gasparini, C., Sette, S., Baumgartner, E., Martin, C. L., & Fabes, R. A. (2015) and Zosuls, K. M., Martin, C. L., Ruble, D. N., Miller, C. F., Gaertner, B. M., England, D. E., et al. (2011). Merrel and Dobmeyer (1996) studied male and female children’s behaviour to conclude that they behaved stereotypically when socializing with others of the same gender: girls expressed more sadness and fear than their male counterparts. Differential social behaviour based on gender has also been studied by Webster-Stratton (1996) who found that boys had more potential to externalize problems like physical aggression and distractibility while girls tended to internalize problems. This theory of aggressive behaviour from boys and prosocial behaviour from girls has also been supported by Walker (2005) and Gür, Ç., Koçak, N., Demircan, A., Baç Uslu, B., Şirin, N., & Şafak, M. (2015). Larsson and Frisk (1999) observed that girls were more socially competent in schools compared to boys, but they scored lower than boys in relation to attention levels. Similar result were found by Jozefiak, T., Larsson, B., Wichstrøm, L., & Rimehaug, T. (2011) who found girls showed more social competence than boys. These results have also been supported by this current study which has found that girls have higher social competence than boys.Social competence can be evident even in babies when they react to adult gestures of voice, eye contact and smiles. Younger children often emulate older children and so the latter’s behavioural pattern can influence the social behaviour of the former. Social competence in children can be cultivated at a very early age with appropriate interventions focussed on risk factors such as having single parents or family problems. In preschool years, social competence interventions can focus on prosocial skills like conflict management. Such interventions can help children to develop skills for peer interaction in the short term, and also reduce risks of substance abuse in the long term. For older children, interventions need to focus on developing self-control, problem solving skills and emotional understanding. Such interventions can reduce aggression levels in children and increase their conflict management skills. Generally, it is assumed that social skills are enhanced as children grow older; however not all children in the same age group behave similarly as each child has a distinct personality, perspective and self-confidence. This current study has found that age is statistically significantly associated with social competence at a 5% level of significance (as evident in the p-values). This finding is supported by other studies too, such as Thompson, E. P., Boggiano, A. K., Costanzo, P., Jean-Anne Matter, J. A., Ruble. D. N. et al. (1995) who observed that older children were more perceptive about their peers’ intentions when they used an ulterior motive or false flattery, than younger ones. They concluded too that first graders could understand the practical value of manipulation to obtain a desired result. In a second study, they found that older children selected partners strategically, i.e. based on their superior skills, so they could get help in accomplishing challenging tasks, whereas younger children were more prone to befriend peers whom they found likeable. According to Rosenblum and Olson (1997), negative traits like social isolation and feelings of neglect that exist in preschool children tend to remain for the entire preschool year, but behavioural patterns like aggressiveness and solitary play behaviour remain low to moderately consistent throughout the entire preschool year. Brownell (1990) observed social behavioural patterns of 18-24 month old toddlers to conclude that they could behave age appropriately when interacting with both slightly older and slightly younger children. In the second year, these children could express themselves more explicitly with their peers and showed increased communication skills. Larsson and Frisk (1999) studied school children to find that older children scored higher on social competence than their younger counterparts, a theory that has been further supported by Jozefiak, T., Larsson, B., Wichstrøm, L., & Rimehaug, T. (2011).The marital status of parents is another factor that contributes toward social traits of all sorts in children. In recent years, many researchers have focused on parental marital status since single parenthood often leads to a constrained parent-child relationship. This current research has concluded that parental marital status is statistically significantly associated with social competence at a 5% level of significance (as evident in the p-values). Children with unmarried parents have a greater chance of social competence. In this context, however, Forehand, Long and Brody (2014) observed that adolescents of divorced parents perceived themselves as socially more incompetent than adolescents of non-divorced parents. Be that as it may, these authors failed to establish any relationship between the level of parental conflict and the adolescent social competence, with the result that the adolescents showed the same level of social incompetence irrespective of whether parental conflict was increasing or decreasing. They did find differentiated effects of parental marital status and conflict on adolescents, though: both these variables were associated with adolescent communication skills, but only parental conflict was associated with cognitive competence. According to Forehand, Long and Brody (2014, p. 159), “marital status is associated with adolescents’ perceptions of their cognitive and social competence, whereas parental conflict was associated with independently assessed competence”. Since parental marital status is often related to parental psychological status (divorce can lead to depressed mothers, for instance), Goodman, S. H., Brogan, D., Lynch, M. E., & Fielding, B. (1993) studied depressed mothers with or without fathers who had psychiatric disorders. It was seen that if fathers had a history of psychiatric disorder which resulted in the divorce, then the mothers’ post-divorce depression had no significant additional negative effect on their children’s social skills. However, if depressed mothers had psychologically fit fathers, then the children had lower social skills, but these children did not show a lower self-concept or less self-control than children with psychologically fit parents. A similar result was found by Finger, B., Eieden, R. D., Edwards, E. P., Leonard, K. E., & Kachadourian, L. (2010) who stated that marital conflict could have a direct effect on mother and father reported peer competence, but marital conflict had an insignificant effect on teacher reported peer competence.Social competence in terms of shyness and low self-confidence is found in varying degrees in children based on their residential status, and this current study has concluded that residential status of children is statistically significantly associated with their social competence at a 5% level of significance (as evident in the p-values). Shyness as a negative social trait has been studied by Chen, Wang and Wang (2009) who studied Chinese children from both rural and urban backgrounds. In the case of urban children, shyness was regarded as a negative trail in both school and social circles. Consequently, it could lead to rejection by peers in cities, and teacher-rated incompetence resulting in poor academic results. For rural school children, on the other hand, shyness could have the opposite result. Rural children who were shy could adjust well in school and for them it was associated with social and school achievement such as leadership and teacher-rated competence.In the context of parental education levels as a variable factor, this current study has found that it is negatively associated with social competence, i.e. the higher the parental level of education, the lower the chance the child has of being socially competent. This has been supported by Maassen and Landsheer (2000) in relation to children’s achievements in math and physics. However, other studies, like Luthar (1991), found an insignificant relationship between children’s school achievement and their social competence. Wentzel (1991) found that children who were neglected by peers were more prone to scoring higher scores in school than children who were moderately popular among peers.Limitation and future scope of researchThe main limitation of this research is the time frame taken, as it might not be applicable five years hence. It remains, though, a snapshot in time for Egypt. Secondly, the results for Egypt might not be generalizable beyond Arab and Muslim countries, as western countries place more emphasis on instructional approaches than disciplinary ones, but it certainly has relevance there. Discipline in the Middle East, in the Arab and Muslim world, comes before education. In those societies, it is seen as logical that if the child is not sufficiently polite, he cannot learn. A bullying and arrogant child will not learn. As a result, our education is originated in the teachings of religion, and as that is where Middle Eastern society is at present, this is the stage that can be researched and where changes can be made.The paper could initiate future research in the same line for other nations, especially western nations and a comparative analysis could then be done between western and non-western nations.

6. Conclusions

- It is believed that the greatest potential hindrances to growing children are their environment and society. Thus, a lack of attention from parents and a distressed home environment (from parental conflict or psychological disorders, financial problems, etc.) can produce low self-confidence and low social skills in children. This is a major issue currently given the increasing number of divorces. However, children are malleable in nature, so to encourage them to remain positive and further develop social skills, parents and teachers need to support them, motivate them and respect them as individuals. Children and adolescents can experience extreme mood swings and emotional changes. As a result, teachers and parents also need to act patiently when dealing with them, as inappropriate interventions can lead to children withdrawing from critical social activities, such as interacting with peers or participating in group activities, and this is situation to be avoided if possible. It is the responsibility of parents and teachers to create favorable conditions for children by paying them greater attention and fostering warm relationships. Since home provides the first social environment for any individual, the supportive attitudes of parents and other family members can enhance social competencies and peer interactions in children. Creating a suitable home environment for emotionally vulnerable children helps minimize their psychological discomfort. School expectations play an important role in the lives of children, so they need to be presented in ways that also encourage the further development of confidence and self-reliance among children and adolescents. As the school provides the second social environment for any individual, the supportive attitudes of teachers are also vital for the child’s well-being.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML