-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2017; 7(2): 36-43

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20170702.02

Character Strengths and Life Satisfaction of High School Students

Edward Abasimi1, 2, Xiaosong Gai1, Guoxia Wang1

1Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education Northeast Normal University, Changchun, China

2School of Allied Health Sciences, University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana

Correspondence to: Edward Abasimi, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education Northeast Normal University, Changchun, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Character strengths are important personal qualities that are proposed to be productive and critical for lifelong optimal human development. This study investigated the distribution of the Values in Action character strengths among high school students and their relationship with satisfaction with life of the students. Using data from a sample of 210 students, results indicated that the top seven strengths were forgiveness, self-regulation, kindness, leadership, hope, love of learning and fairness whiles the least five were creativity, bravery, perseverance, curiosity and appreciation of beauty. Judgment, zest, love, kindness, prudence and humor independently significantly correlated with subjective wellbeing. Regression results showed that bravery, judgment, prudence, gratitude and humor made significant contribution in explaining subjective wellbeing with bravery making the largest unique contribution. Females scored significantly higher than males on five strengths. Implications of the findings for research, practice and emerging adulthood development of character strengths are discussed.

Keywords: Character strengths, Life satisfaction,High school students

Cite this paper: Edward Abasimi, Xiaosong Gai, Guoxia Wang, Character Strengths and Life Satisfaction of High School Students, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 7 No. 2, 2017, pp. 36-43. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20170702.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

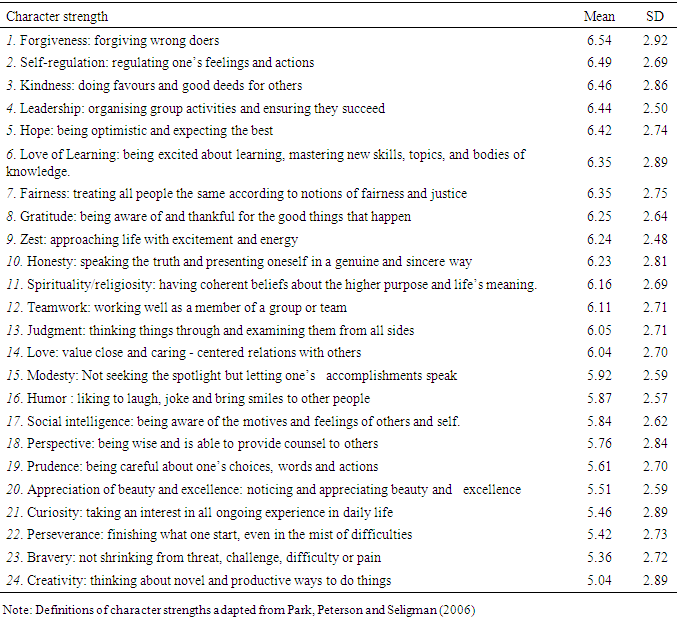

- The call by some psychologists for researchers to focus on the positive aspects of individuals as much as repairing the negative is receiving positive response in recent times. This is evident from the increased research interest in personal and psychological strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Character strengths (CSs) and positive experiences such as satisfaction with one’s life are aspects of positive psychology (Park, Peterson & Seligman, 2004) that have recently caught the attention of researchers across the globe. Peterson and Seligman (2004) who identified 24 ubiquitously endorsed CSs and classified them into 6 core virtues, defined them as the positive personal qualities that leads to human flourishing and that they can be measured in degrees. The 6 virtues into which the CSs were classified consists of wisdom and knowledge (creativity, curiosity, perspective, love of learning, judgment); courage (bravery, industry, integrity, zest); humanity(Love, kindness, social intelligence); justice (citizenship, fairness, leadership); temperance (forgiveness, modesty, prudence, self control) and transcendence (appreciation of beauty, gratitude, hope humor, spirituality). Peterson and Seligman (2004) and Park, Peterson and Seligman (2006) defined wisdom and knowledge strengths as cognitive strengths that has to do with acquisition and use of knowledge. Courage strengths entail those that involve the exercise of will to achieve goals in the mist of opposition. Interpersonal strengths that involve “tending and befriending” others have been named humanity strengths. Justice strengths are those that support healthy community life while temperance strengths protect against excesses and finally, transcendence ones foster connections to the larger universe and provide meaning. The conceptualisations of the individual strengths under these broad categorisations are as summarised in Table 1. Following the identification and classification of these strengths in the Value in Action (VIA) project and the development of a measure, the Values In Action Inventory of strengths (VIA-IS) to asses them, several studies have focused on these strengths, their structure and measurement, distribution, the importance of possessing and using them (Abasimi & Gai, 2016; Duan, Ho, Tang, Li & Zhang, 2014; Gentry et al. 2013; Mcgrath, 2012; Wood, Linley, Maltby, Kashdan & Hurling, 2011) and their relationship with various aspects of wellbeing among adults and to a lesser extent, youth (Neto, Neto & Furnham, 2014; Noronha & Martins, 2016; Toner, Haslam, Robinson & Williams 2012). Most of the studies have found kindness and honesty among the top strengths and modesty and prudence among the bottom ones (McGrath, 2015; Park, Peterson & Seligman, 2006).

1.1. Distribution of Character Strengths

- Park et al. (2006) examined the 24 CSs in 54 nations and the 50 US states among adults and found that the most prevalent strengths in the USA were kindness, fairness, honesty, gratitude and judgment and the lesser ones include prudence, modesty and self-regulation. Character strengths profile in the USA was similar to profiles from other nations with the exception of religiosity. In this large scale study, only 2 African countries, South Africa and Zimbabwe were involved. Recently, McGrath (2015) updated Park et al.’s (2006) study by investigating the strengths in 75 nations using a sample of 1063,921 adults with each nation represented by at least 150 respondents. Even though 6 African countries were included in this updated study, with the exception of South Africa, the sample sizes in the African countries were relatively very small. The most prevalent strengths were honesty, fairness, kindness, judgment and curiosity whiles the least prevalent ones were self-regulation, modesty, prudence and spirituality. Shimai, Otake, Park, Peterson and Seligman (2006) found similar distribution of the 24 CSs among American and Japanese samples. Top strengths included love, humor and kindness and lesser ones were prudence, self regulation and modesty. Abasimi and Gai (2016) in a recent study among teachers in Ghana using the Character Strengths Rating Form (CSRF) (Ruch, Martinez-Marti, Proyer & Harzer, 2014)found that the top 7 CSs were gratitude, kindness, fairness, love of learning, honesty, perspective and judgment.

1.2. Character Strengths and Subjective Wellbeing

- Specific strengths such as love and zest have been found to predict subjective wellbeing (SWB) and more specifically satisfaction with life (SWL). For example, in three large studies among adults, Park et al. (2004) found that hope, zest, gratitude, love and curiosity were strongly associated with life satisfaction whiles modesty, appreciation of beauty, creativity, judgment and love of learning were weakly associated with it. Toner et al. (2012) examined the structure of CSs among adolescence aged between 15 and 18 in Australia and obtained five strength factors including temperance, vitality, curiosity, interpersonal strengths and transcendence. Temperance, vitality and transcendence were independently associated with wellbeing and happiness. Specifically, hope, caution, zest, fairness and leadership predicted both life satisfaction and happiness. Curiosity and love also predicted greater happiness while fairness further predicted greater life satisfaction. Noronha and Martins (2016) found that hope, vitality, gratitude, love, curiosity, perseverance and social intelligence strengths were positively correlated with life satisfaction. Abasimi and Gai (2016) found a strong positive relationship between overall CSs and SWL. Creativity, perspective, love, teamwork, prudence, and gratitude were each significantly correlated with SWL. Prudence, humor, modesty, self-regulation and love each made unique and significant contribution in explaining life satisfaction. Other studies (e.g., Gilham et al., 2011; Leontopoulou & Triliva, 2012; Lim, 2015; Neto et al., 2012; Rashid et al. 2013) have reported associations between CSs and SWB. As CSs are malleable (Peterson & Seligman, 2004), easier to cultivate in youth (Rashid et al., 2013), and are linked to wellbeing indicators, assessing the CSs and their link with important wellbeing indicators such as satisfaction with life among high school students, the future leaders of society, is important as this will enable us design intervention programs aimed at cultivating critical CSs and enhancing life satisfaction. Even if CSs do not relate to wellbeing, some researchers are of the view that they are of themselves morally valued and that their mere assessment among the youth constitutes an intervention (Rashid et al., 2013). Unfortunately, despite the significance of Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) CSs in their own right and their proposed link with important wellbeing indicators, little is known about their distribution among high school students as well as their link with the students’ satisfaction with life. In addition, many of the studies so far have been conducted among adult samples in western and to some extent Asian countries (Dahlsgaard, Peterson & Seligman, 2005; Mcgrath, 2015; Park et al., 2006). Almost no previous research has examined the distribution of CSs and their link with SWB among high school students (youth) in an African context and for that matter Ghana, except the study of Van Eeden, Wissing, Dreyer, Park and Peterson (2008) which sought to validate the VIA-Youth among South African learners. Even though the VIA CSs may be ubiquitous among adults as claimed by Peterson and Seligman (2004), little is known about this among school children (youth). In addition, the nature of their distribution may be influenced by cultural or traditional values (Lim, 2015). The findings of the present study in addition to being important could have implications for emerging adulthood development. First, by examining the Cs distribution of the youth (mainly adolescents and young adults in the present study), we could determine a potential link between their strengths and that of significant adults such as teachers in their lives. This is important as it may help teachers and adults realize the importance of being good role models for the young adults. Similarly, an establishment of a link in Cs and satisfaction with life among the youth would help us determine how similar the development of emerging adults and that of adults is since previous studies have examined this link among adults.The current study thus sought to investigate the distribution of Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) CSs among senior high school students in selected schools in Ghana, and the relationship between the strengths and their SWL as well as gender differences in the CSs. It should be noted that high school in Ghana is divided into junior and senior high. Whereas junior high school students are those in grades 7-9 with ages ranging mainly from 13-15, senior high students are those in grades 10-12 with ages mainly from 16 and above. Although most studies on the relationship between CSs and SWL had focus on adults, the measurement of SWL in adults differs from that of school children and youth because SWL of school children and youth is heavily influenced by satisfaction with school (SWS) (Tomyn & Cummins, 2011). Whereas satisfaction with life of adults, which is defined as the global assessment of the quality of life (Diener et al., 1985), has traditionally been assessed with the SWL scale of Diener et al. (1985), Tomyn and Cummins (2011) proposed a different measure for assessing SWL among school children and high school students that include an item specifically assessing satisfaction with school.

1.3. Gender and Character Strengths

- Gender has been suggested to influence behavior and individual difference variables in several ways. Researchers are therefore interested in examining the influence of gender on individual difference variables such as CSs. Previous studies (e.g., Linley et al., 2007; Park et al., 2004; Shimai et al., 2006) have examined gender differences in CSs and found gender differences in specific strengths with females generally scoring higher, even though most of these have been conducted among adults. This study, thus sought to confirm whether the proposed gender differences are replicated in SHS students in the study area. For example, Linley et al. (2007) found that except for creativity, women scored higher in all the 24 strengths in the UK among a large internet sample while Shimai et al. (2006), in a comparative study found gender differences in 10 of the 24 strengths and the results were similar among Japanese and American cultures. The few studies that examined gender differences among young people in western countries include the studies of Toner et al. (2012), Neto et al. (2012) and Park and Peterson (2005). Toner et al. (2012) found gender differences in their young sample from Australia with females scoring significantly higher in 7 strengths including wisdom, bravery, love, kindness, fairness, humor and appreciation of beauty and excellence. Neto et al. (2012) found that young Portuguese female students aged from 12 to 20 generally scored higher than their male counterparts on many of the CSs including judgment, social intelligence, honesty, kindness, love, citizenship, fairness, humility, gratitude, forgiveness and enthusiasm. Park and Peterson (2005) also found gender differences in many of the 24 CSs (appreciation of beauty, love, kindness, wisdom, open-mindedness, gratitude and spirituality) among adolescents with females scoring higher.With the increasing evidence suggesting that females score higher on many of the 24 strengths, this study sought to confirm whether the proposed differences are replicated in them in the study area since evidence on the youth are limited. Thus, the present study’s aim of examining the distribution of the 24 CSs and their relationship with SWL as well as gender differences in the strengths among SHS students is warranted. Based on the previous studies, it is anticipated that (i) wisdom and knowledge strengths such as creativity, curiosity, and love of learning will be among the top 7 strengths of the students (ii) specific CSs will positively predict SWL (as CSs are psychologically fulfilling , Peterson & Seligman, 2004) and (iii) there will be significant gender differences in specific CSs.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants and Procedure

- Participants were 210 high school students of first (n = 37, 17.6%), second (n = 49, 23.3%) and third (n = 124, 59%) years from two schools in the Builsa district of the Upper East region of Ghana. Participants’ age ranged from 16-22 (average age = 18 years; SD = 1.57201). It should be noted that senior high school students in Ghana are high school students in grades 10-12 with ages mainly from 16 and above. Even though it is common to have students with ages ranging from 16 to 22 in Ghanaian high schools, majority of them are between ages 17 and 18. A good number of participants (n = 107, 51%) were females. Religiously, majority (n = 172, 81.9%) were Christian, followed by Muslim (n = 31, 14.8%) and then traditional (n = 7, 3.3%). Participation was voluntary and parental informed consent was obtained for participants under 18 years (very few cases) after permission for the study was obtained from the schools’ authorities. The first author gave basic explanation about the study as well as motivated the students to complete the questionnaire frankly as information they provided was meant solely for research purposes and that confidentiality was assured. Participants completed questionnaire within an average of 25 minutes for immediate collection by teacher and the researcher.

2.2. Measures

- The Character Strength Rating Form (CSRF; Ruch et al., 2014) and the Personal Wellbeing Index for School Children (PWI-SC; Tomyn & Cummins, 2011) was used to collect data. These instruments were both pilot tested and found suitable before actual administration.(a) The Character Strengths Rating Form The CSRF is designed based on the VIA-IS (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) to asses character strengths and consist of 24 items assessing the 24 CSs with each strength briefly described and participants are expected to indicate the extent to which each statement (CS) describes what they are like. The CSRF has typically been used to assess the CSs of adolescents and adults (e.g., Ruch et al., 2014) with age ranging from 18. Thus the current sample includes few participants who are only slightly below this age. The pilot study we conducted in Ghana prior to this study also revealed that the CSRF is simple to understand and valid with high psychometric properties among the current sample aged 16 to 22. Response options of the CSRF range from 1= very much unlike me to 9= very much like me. A sample item is Creativity- “Creative people have a highly developed thinking about novel and productive ways to solve problems and often have creative and original ideas. They do not content themselves with conventional solutions if there are better solutions”. The CSRF yielded good convergence with the VIA-IS among German speaking adults (Ruch et al., 2014). The CSRF was also used in a study among teachers (Abasimi & Gai, 2016) in the same study area in Ghana and replicated findings using the VIA-IS. (b)The Personal well-being Index for School Children (PWI-SC)The PWI-SC consists of 8 items indicating how satisfied people are with various aspects of their lives including school. It is designed to assess SWL and school among adolescents and young people. It has mainly been used to assessed the subjective wellbeing of high school students with ages ranging from 12 to 20 years (Tomyn & Cummins, 2011; Tomyn, Norrish & Cummins, 2013; Tomyn, Weinberg, & Cummins, 2014). The present sample’s age range is thus similar to that of previous samples. It uses a response category ranging from 1-7 (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree,) and respondents indicated how satisfied they were with each aspect of their life including satisfaction with school. A sample item is “I am satisfied with my personal health”. The 8th item states that “I am satisfied with my school as a whole”. Tomyn and Cummins (2011) reported a Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient of .83 in the young sample they studied in Australia. In the present study, a cronbach alpha reliability of .71 was obtained indicating that the instrument is reliable in the current sample.

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of Character Strengths

- To find out the distribution of the CSs, we computed descriptive statistics obtaining the means and standard deviations for all strengths. The means and standard deviations were then rank ordered (see Table 1). From the results, the top seven strengths were forgiveness, self regulation, kindness, leadership, hope, love of learning and fairness whiles the bottom five strengths were creativity, bravery, perseverance, curiosity and beauty. Hypothesis 1 was therefore not fully supported. The reasoning behind hypothesis 1 was that the wisdom and knowledge strengths, also referred to as intellectual or cognitive strengths (Toner et al., 2012) are related to learning and education ( Harzer & Ruch 2013; Peterson & Seligman, 2004) and once students are mainly engaged in learning they are more likely to report having them than the other strengths. However this was not the case.

|

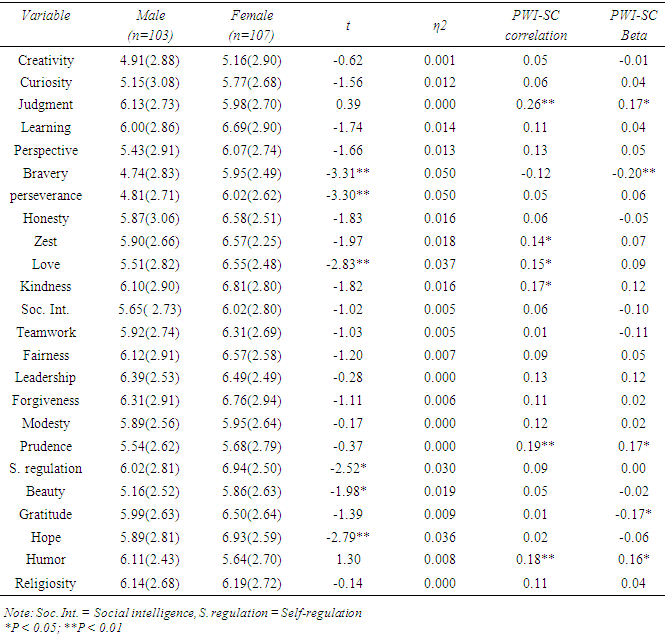

3.2. Character Strengths and Satisfaction with Life

- To examine the correlation between strengths and SWL, the Pearson’s Product Moment correlation was conducted. Results are presented in Table 2. Six strengths significantly correlated with SWL. These include judgment (r (210) =. 25, p < .01, zest(r (210) = p < .05, love (r (210) =. 15, p < .05, kindness (r (210) =. 17, p < .05, prudence (r (210) = .19, p < .01 and humor (r (210) = .18, p < .01.To examine the predictive power of strengths on SWL, we conducted standard multiple regression analysis. The results are as presented in Table 2. A significant model emerged when the dependent variable of SWL was regressed on the various strengths, F (24, 185) = 1.963, p < .01). All the predictors (24 CSs) together explained 20% (R2 = .203) of the variance in SWL. Five strengths made a significant contribution to the model. Bravery made the largest unique and significant contribution (β = -.20, P = .007). Both correlation and regression results indicate that the top strengths of the students are not necessarily associated with their wellbeing.

3.3. Gender and CSs

- To determine whether gender differences exist in the strengths, we compared males and females on each of the 24 strengths using the independent samples t-test (see Table 2). The results show that there was no significant difference in the scores of males and females on many of the strengths. Females scored significantly higher than males in 6 strengths. These include bravery, perseverance, love, self- regulation, appreciation of beauty and hope. For bravery, the scores for females (M = 5.95, SD = 2.49) and that of males (M = 4.47, SD = 2.83), [t (208) = -3.311, p = 001]. For perseverance, the scores for females (M= 6.02 , SD = 2.62) and that of males (M = 4.81, SD = 2.71), [t (208) = -3.298, p = .001]; for love , the scores for females (M= 6.55 , SD = 2.48) and that of males (M = 5.51, SD = 2.82), [t (208) = -2.831, p = .005]; for self regulation, the scores for females (M= 6.94 , SD = 2.50) and that of males (M = 6.02, SD = 2.81), [t (208) = -2.521, p = .012]; for beauty, the scores for females (M= 5.86 , SD = 2.63) and that of males (M = 5.16, SD = 2.81), [t (208) = -1.981, p = .049] and for hope, females scored (M = 6.93, SD = 2.56) and males scored (M = 5.89, SD = 3.42), [t (208) = -2.794, p = .006]. It is worth noting that even though there were significant differences in these strengths, the magnitude of the differences were very small for all of them (Cohen, 2013) as can be seen from the eta squared values.

4. Discussion

- The Current results failed to fully confirm the researchers’ expectation that wisdom and knowledge strengths such as creativity, curiosity and love of learning will be among the top 7 strengths. The only wisdom and knowledge strength among them is love of learning. This hypothesis was premised on the fact that the wisdom and knowledge strengths, also referred to as intellectual or cognitive strengths (Toner et al. 2012) have to do with acquisition and use of knowledge and are thus related to learning and education (Harzer & Ruch, 2013; Park et al., 2006). It was therefore thought that since students are mainly engaged in learning they would report more of these strengths. However, this was not the case. However, the fact that love of learning is among the top 7 strengths disconfirms the popular notion in the study area that SHS students’ desire and motivation to learn has decreased in recent times. Abasimi and Gai (2016) also found love of learning as one of the top 5 strengths among teachers in the study area. The distribution of the strengths in the present study is generally similar to that of Abasimi and Gai (2016) in the sense that 3 of the top 7 strengths of teachers (kindness, fairness, love of learning) found by them is also among the top 7 found by the present study and 3 of the bottom 7 strengths (bravery, perseverance, creativity) found by them is in the bottom strengths of the present study. Similarly, two of the strengths (love, prudence,) that correlated with life satisfaction in the study of Abasimi and Gai (2016) also correlated with SWL (PWI-SC scores) in the present study. Based on these findings, it seems the CSs of the high school students and their teachers are related. The fact that temperance strengths (forgiveness and self-regulation) are the topmost strengths among the students is important as these protect against excesses (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). The implication is that these strengths have the potential to make the students disciplined and have controlled appetites and emotions which are good. Even though the pattern of the present findings is somewhat different in terms of the distribution of the top and bottom strengths from that of the studies of Park et al. (2006), Shimai et al. (2006) and McGrath (2015), what it has in common with them is that the strength of kindness is among the top five of all of them. Thus the strength of kindness seems to be highly endorsed in various samples and geographical locations. As noted earlier, few studies have been conducted on Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) 24 CSs among SHS students in general and particularly in Ghana. The present study is therefore among the first to examine this. Studies done among the youth mainly in developed countries such as that of Neto et al. (2014) did not examine the distribution of CSs. We believe it is important to examine the distribution of the strengths among the SHS students as it enables us understand their top strengths and hence make recommendation for the cultivation of critical ones in them. The present study thus provides baseline information on this in the study area in Ghana.With regards to the relationship between CSs and SWL, the strengths of judgment, zest, love, kindness, prudence and humor significantly correlated with SWL. This confirms our anticipation that specific CSs would be positively associated with SWL (i.e., PWI-SC scores). The finding is consistent with Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) assumption that the CSs are generally fulfilling. It is also consistent with a number of previous studies (e.g., Leontopoulou & Triliva 2012; Toner et al., 2012). It is consistent with Neto et al. (2014) who found a link between overall CSs and life satisfaction of Australian youth and that of Toner et al.’s (2012) finding that strength factors (temperance, vitality, transcendence) were independently associated with wellbeing and happiness among Australian high school students. The present finding is also consistent with that of Park et al.’s (2004) finding among others that love and zest were strongly positively associated with life satisfaction even though their study was conducted among adults using internet samples.Concerning the predictive power of the CSs on SWL, our results revealed that only the five strengths of bravery, judgment, gratitude, prudence and humor made unique significant impact on wellbeing. It was however surprising that although the strengths of bravery and gratitude did not correlate with SWL, they each significantly predicted it, and more so negatively. The fact that bravery made the strongest (negative) contribution in explaining SWL (PWI-SC) is inconsistent with Toner et al. (2012). Strength factors that predicted PWI-SC scores in the present study were generally different from those that predicted PWI-SC scores in Toner et al. (2012) study although judgment and prudence were common predictors in both studies. In the present study whereas bravery, judgment, gratitude, prudence and humor predicted PWI-SC scores, in that of Toner et al. (2012), 7 factors that predicted PWI-SC scores were different. The difference in the findings of the two studies might be as a result of the use of different measures for CSs. Whereas Toner et al. (2012) used the VIA –Youth scale, the present study used the CSRF. Even though scores on the CSRF has been found to converge well with that of the VIA-IS (Ruch et al., 2014), the CSRF may be less sensitive. The differences might also be due to cultural or geographical differences.Consistent with previous studies, in the present study there were significant gender differences in 6 of the strengths (bravery, perseverance, love, self-regulation, appreciation of beauty and excellence and Hope) with females scoring higher. Previous studies (e.g., Neto et al., 2014; Park et al., 2004; Linley et al., 2007; Shimai et al., 2006) found significant gender differences in many of the CSs with females typically scoring higher than males even though some other studies have found gender differences in few of them. Except for creativity, Linley et al. (2007) found women scoring significantly higher in all strengths in the UK among a large internet sample. It is worth noting that although there were gender differences in some of the CSs in the present study with females mainly scoring higher, the differences were marginal. Even though consistent with previous findings, it is quite surprising that females scored significantly higher in the strengths of bravery and perseverance in the present sample. This is because popular culture and perception in the study area generally has it that males are braver and generally persevering. This study thus provides initial evidence to disprove that perception. It is therefore recommended that further research using larger samples across several schools are conducted in Ghana to substantiate this evidence.

5. Conclusions

- The question of why creativity and curiosity (wisdom and knowledge strengths) is among the bottom 6 CSs of high school teachers (Abasimi & Gai 2016) and students (present study) in the study area demand answers. A large scale study may be helpful in confirming the findings. However, based on the present findings, it is recommended that parents, teachers, government and stakeholders of education find ways of motivating students to be creative and develop the desire to learn. Therefore the institution of incentives schemes for students who excel in creativity and academic work could be helpful motivational tools. Even though love of learning is among the top 7 strengths of the students, when motivated, they could improve upon their desire to learn. Senior high school students and the youth in general in the study area should be encouraged to cultivate the strengths of zest, love, kindness, judgment, prudence and humor since they are critical in promoting SWL among them. In that vein, it is recommended that the introduction of the religious and moral education programmes in the junior high schools in Ghana aimed at helping students cultivate some of these strengths is a good thing and should be encouraged and extended to the senior high schools. Based on the findings that males generally scored lower on specific strengths, it is recommended that they are particularly targeted in CSs training and intervention programs focused on developing those strengths.

6. Limitations

- Despite being one of the first to examine the distribution of CSs and their link with satisfaction with life among the students, thus providing baseline information with potential to stimulate future research on CSs and wellbeing among students in Ghana and beyond, the study has a number of limitations. First, the sample size is small and thus limits the generalizability of the findings. It is important that future research on CSs in the study area and Ghana in general, use larger samples across several schools in several districts as opposed to the two schools in the one district the present study was able to cover. Related to the limitation of the sample is the fact that the sample consisted of both adolescents and young adults as can be seen from the age range of 16-22. Future studies should focus on either adolescents or young adults or at least a comparison of the two groups. On a whole however, the present study’s findings are important as they have replicated previous findings that used larger samples and the lengthy VIA-IS to asses CSs. Another limitation of the present study is its use of self-report measures. The use of self report measures have often been argued to be susceptible to bias and socially desirable responding. To address this limitation, future researchers could supplement findings of self report measures with peer ratings and interviews.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- The authors wish to thank the headmasters and students of the schools where data was collected for their cooperation and participation.

References

| [1] | Abasimi, E., & Gai, X. (2016). Character strengths and life satisfaction of teachers in Ghana. Humanities and Social Sciences Letters, 4(1), 22-35. |

| [2] | Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Academic press. |

| [3] | Dahlsgaard, K., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Shared Virtue. The convergence of valued human strengths across culture and history. Review of General Psychology, 9, 203-213. |

| [4] | Diener, E., Emmons, R. Larsen, R., & Griffin. S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75. |

| [5] | Duan, W., Ho, S.Y.H., Tang, X., Li, T. & Zhang, Y. (2014). Character Strength-Based Intervention to Promote Satisfaction with Life in the Chinese University Context. Journal of Happiness Studies 15(6), 1347-1361. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9479-y. |

| [6] | Furnham, A., & Lester, D. (2012). The development of a short measure of character strengths. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28, 95-101. |

| [7] | Gentry, W.A., Cullen, K. L, Sosik, J.J., Chun, J.U, Leupold, C.R., & Tonidandel, S. (2013). Integrity’s place among the character strengths of middle-level managers and top-level executives. The Leadership Quarterly, 24, 395-404. |

| [8] | Gillham, J., Adams-Deutsch, Z., Werner, J., Reivich, K., Coulter-Heindl, V., Linkins, M., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Character strengths predict subjective well-being during adolescence. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6, 31-44. |

| [9] | Harzer, C., & Ruch, W. (2013). The application of signature character strengths and positive experiences at work. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 965-983. |

| [10] | Leontopoulou, S., & Triliva, S., (2012). Explorations of subjective wellbeing and character strengths among a Greek University student sample. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2 (3), 251-270. |

| [11] | Lim, Y. (2015). Relations between virtues and positive mental health in a Korean population: A multiple indicators multiple causes (MIMIC) model approach. International Journal of Psychology, 50 (4) 272–278, DOI: 10.1002/ijop.12096. |

| [12] | Linley, P. A, Maltby, J., Wood, A. M, Joseph, S., Harrington, S., Peterson, C., et al. (2007). Character strengths in the United Kingdom: The VIA Inventory of strengths. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 341-351. |

| [13] | Neto, J., Neto, F., & Furnham, A. (2014). Gender and psychological correlates of self-rated strengths among youth. Social Indicators Research, 118, 315-327. |

| [14] | Noronha, A. P. P. & Martins, D. F. (2016). Associações entre Forças de Caráter e Satisfação com a Vida: Estudo com Universitários. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 19(2), doi: 10.14718/ACP.2016.19.2.5. |

| [15] | McGrath, R. E. (2012). Scale- and Item-Level Factor Analyses of the VIA Inventory of Strengths. Assessment XX(X) 1–11. |

| [16] | McGrath, R. E. (2015). Character strengths in 75 nations: An update. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10 (1), 41-52. |

| [17] | Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). The values in action inventory of character strengths for youth. In K.A. Moore & L.H. Lippman (Eds.). What do children need to flourish: Conceptualising and measuring indicators of positive development (pp.13-23). New York: Springer. |

| [18] | Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23 (5), 603-619. |

| [19] | Park, N., Peterson, C. & Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Character strengths in fifty-four nations and the fifty US states. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(3), 118-129. |

| [20] | Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook of classification. Washington, DC: APA Press. |

| [21] | Rashid, T., Anjum, A., Lennox, C., Quinlan, D., Niemiec, R. M., Mayerson, D., & Kazemi, F. (2013). Assessment of character strengths in children and adolescents. In Research, applications, and interventions for children and adolescents (pp. 81-115). Springer Netherlands. |

| [22] | Ruch, W., Martinez-Marti, M. L., Proyer, R. T., & Harzer, C. (2014). The Character Strength Rating Form (CSRF): Development and initial assessment of a 24-item rating scale to asses character strengths. Personality and Individual Differences, 68, 53-58. |

| [23] | Shimai, S., Otake, K., Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Convergence of character strengths in American and Japanese young adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 311-322. |

| [24] | Tomyn, A. J. & Cummins, R. A. (2011). The subjective wellbeing of High- School students: Validating the Personal Wellbeing Index - School Children. Social Indicators Research, 101,405- 418. DOI 10.1007/sl120 5-010-9668-6. |

| [25] | Tomyn, A. J., Norrish, J. M., & Robert A. Cummins, R. A. (2013).The subjective wellbeing of Indigenous Australian adolescents: Validating the Personal Wellbeing Index-School Children. Social Indicators Research, 110, (3), 1013-1031. |

| [26] | Tomyn, A.J., Weinberg, M.K., Cummins, R. A. (2014). Intervention efficacy among ‘At Risk’ adolescents: A test of subjective wellbeing homeostasis theory. Social Indicators Research. DOI 10.1007/s11205-014-0619-5. |

| [27] | Toner, E., Haslam, N., Robinson, J., & Williams, P. (2012). Character strengths and wellbeing in adolescence: Structure and correlates of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Children. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 637-642. |

| [28] | Van Eeden, C., Wissing, M., Dreyer, J., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2008). Validation of the values in action inventory of strengths for youth (VIA-Youth) among South African learners. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 18(1), 143–154. |

| [29] | Wood, A. L., Linley, P.A., Maltby, J., Kashdan, T.B., & Hurling, R. (2011). Using personal and psychological strengths leads to increase in well-being over time: A longitudinal study and the development of the strengths use questionnaires. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 15-19. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML