-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2017; 7(1): 10-18

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20170701.02

Evaluation of an Online Educational Tool Designed to Reduce Stress and Boost Well-being for People Living with an Ileostomy: A Framework Analysis

Johanna Spiers1, Adam R. Nicholls1, Phillip Simpson2

1Department of Sport, Health, and Exercise Science, University of Hull, United Kingdom

2York Teaching Hospital, National Health Service Foundation Trust, United Kingdom

Correspondence to: Adam R. Nicholls, Department of Sport, Health, and Exercise Science, University of Hull, United Kingdom.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Ileostomies, in which the small intestine is re-directed out of a stoma in the stomach so that waste is collected using a bag, are using to treat conditions such as bowel cancer and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Previous research has shown that life with an ileostomy can be challenging. In our own previous work, we piloted an Online Educational Tool (OET) designed to reduce stress and boost well-being in people living with an ileostomy. The current study utilised the qualitative method framework analysis in order to evaluate the effectiveness of our OET. We asked nine OET users questions about their experience of using the tool and the impact it may have had on their lives. Feedback was generally positive. Participants described facilitators and barriers for remaining engaged, and discussed a wide range of elements which were successful or unsuccessful. Stress levels were generally reduced and well-being boosted; participants gave examples of how this played out for them. Feelings about whether the impact of the tool would last were mixed. There was one participant who felt the tool was not inclusive enough and too repetitive. Findings from this study add weight to previous findings that the OET was successful in its aims.

Keywords: Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Interviews, Online Interventions, Stoma

Cite this paper: Johanna Spiers, Adam R. Nicholls, Phillip Simpson, Evaluation of an Online Educational Tool Designed to Reduce Stress and Boost Well-being for People Living with an Ileostomy: A Framework Analysis, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 10-18. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20170701.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Ileostomies, in which the small intestine is re-directed out of a stoma in the stomach so that waste is collected using a bag, are used to treat conditions including Inflammatory Bowel Disease (such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) and bowel cancer. More than 9,000 ileostomy operations are carried out in the UK every year [1], whilst 120,000 ostomy operations are performed in the US annually, with 32.2% of these being ileostomies [2]. Existing research suggests that adjusting to an ileostomy is a psychologically challenging experience which involves stressors relating to body image and attitudes to sex [3, 4]. In addition, people living with an ileostomy can experience stressful incidents such as surgical complications, opiate dependency, challenges to their identity, and physical complications following surgery as well as difficult relationships with healthcare teams [5, 6]. Building on existing research into stressors for people living with an ileostomy, we constructed a 10 week Online Educational Tool (OET), designed to reduce stress and boostwell-being in this patient group [7]. The OET consisted of 10 weekly sessions, designed by the team using Survey Monkey. Participants were sent a session at the same time each week for 10 weeks. A reminder email was sent five days later to any participants who had not completed the session for that week. Each week of the OET presented a combination of factors including information, videos, and positive psychology exercises on a particular topic, such as understanding and managing stress, mindfulness, or gratitude. Quotes from our previous qualitative research into life with an ileostomy [5, 6] were utilised throughout the OET in order to give it more resonance for the users. The findings of these previous studies also informed the design of the OET by providing relevant emphases for the weekly topics. For example, week four, which focused on controllable and uncontrollable stressors, utilised a exercise about stress, which included anonymised scenarios, fictionalised from a selection of data given to us by our previous participants. The OET was piloted, and results suggested that the tool was successful, both in terms of stress being reduced and well-being boosted [7]. We set out to further evaluate the success of the tool by utilising qualitative methods to ask participants who had completed the tool about their experience of using it and how (if at all) it had impacted on their lives. We also hoped that these findings would help us to improve upon the tool to make it stronger for future users. It should be noted that we have therefore used qualitative methods both to inform and evaluate our OET, strengthening the design of the tool and the validity of results arising from it [8, 9]. Various authors have highlighted the benefits of using qualitative methods in order to evaluate interventions [8-14]. In particular, Lewin and colleagues [8] stated that qualitative methods can be employed to understand the reasons for the findings of the trial that tested the intervention; variations in effectiveness of the intervention within the sample; the appropriateness of underlying theory; and as a tool to generate further questions about the intervention. Qualitative methods can also be used to determine the ways in which participants change their behaviours following taking part in an intervention [10, 12], to illuminate any improvements that could be made to the intervention [11] and to find out if the participants are as satisfied with the results as the researchers are [14]. The aims of this study were to evaluate participants’ experience of using our OET, as well as to determine how the tool impacted on their lives following their completion of it. We also asked participants about any potential improvements we could make to the tool. We used the qualitative method framework analysis (FA) in order to meet these aims. FA was developed in the context of applied qualitative research [15] and is widely used by health researchers [16]. It is flexible, as it can be either inductive, deductive, or a mixture of the two [17]. Ritchie and Spencer [15] state that it is a useful tool for asking contextual, diagnostic, evaluative and strategic questions of data. Since we are hoping to evaluate and improve our applied OET, FA seems the best fit for this study.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

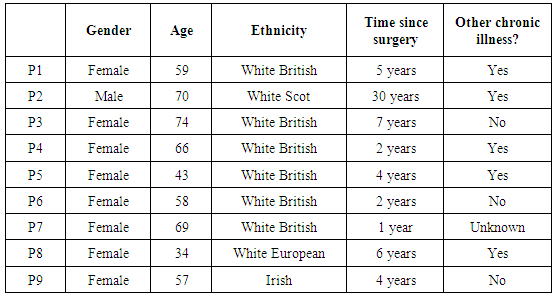

- There were 62 participants who started our OET; 43 of these completed the tool. We emailed these 43 participants asking if they wished to take part in a short interview. It was explained that this would be a chance to feed back about their experience of using the OET and talk about any impact it had had on their lives. Of these participants, nine got back in touch and agreed to be interviewed. It would have been beneficial to speak to some of the 19 participants who started the OET but did not complete it in order to learn about what had caused them to drop out. However, since participants had either dropped out of the study by no longer responding to emails or by contacting us to let us know that health issues prevented them taking any further part, a decision was made that it would not be ethical to contact these people to ask for further participation in our research.Demographic information for the participants appears in Table 1, below. As the table shows, eight of the participants were female. The youngest participant was 34 and the oldest 74. There was also a wide spread of length of time since surgery, from one year to 30 years. Five of the participants had other chronic illnesses (e.g., Diabetes, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease or Arthritis etc) as well as the ones which had led to them having an ileostomy.

|

2.2. Interviews and Ethics

- Information sheets were emailed to each participant, who then gave informed consent to the first author, either by email or through the post. The first author, who is an experienced qualitative health researcher, conducted all nine interviews. Seven of the interviews took place over the phone. One took place via Skype. The final interview, with a participant who is deaf, took place over email. The telephone and Skype interviews lasted between 17 and 53 minutes (mean = 30 minutes). Participants were interviewed between one and six weeks after finishing the OET in order to explore a range of time spent living with knowledge of the skills learnt via the OET. Participants were asked a series of open-ended questions, firstly about their experience of using the OET, and secondly about the impact it had had on their lives. The interviewer followed up any points of note that the participants bought up. Ethics were granted by the relevant university board.

2.3. Analysis

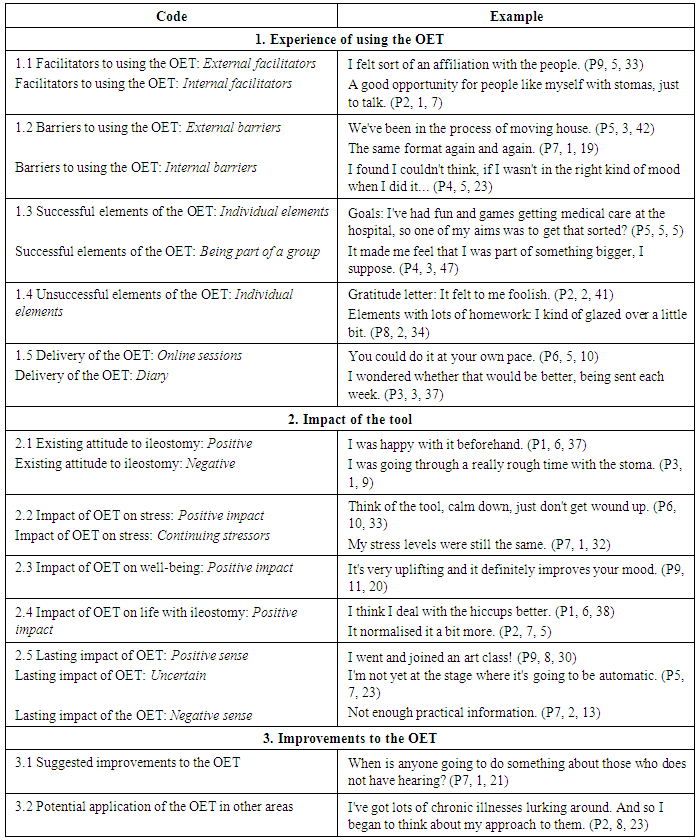

- The transcripts of the nine participants were subjected to a framework analysis [15, 16] using NVivo software. The first author read and analysed the first three transcripts, looking for points of note which corresponded to those elements of a priori interest (experience of using the OET and impact of the OET), as well as additional points that inductively arose from the data. In this way, we utilised a combination of deductive and inductive investigation to analyse the data [16]. A basic framework was derived from this initial analysis, which aimed to represent the diversity of the data [15]. Remaining interviews were then analysed according to this framework. Whilst the data mostly fitted neatly into the initial framework, the framework itself was also altered based on these remaining transcripts. Once all transcripts had been analysed, a complex matrix was drawn up, in which an example from the text for every participant was entered into a cell design for every element of the framework [16]. This matrix was then condensed down into a final framework. Analysis continued as the findings were written up, based on this final framework. Initial and final frameworks were audited by the second author. All authors contributed to the final write up of the findings. As can be seen from Table 2, the final framework comprises three codes: Experience of using the tool; Impact of the tool; and Possible improvements to the tool. Each of these codes breaks down into smaller elements.

|

3. Results

- We spoke to nine participants, and developed a framework with three main codes which described a) those participants’ experience of using our OET, b) the impact the tool had on their lives, and c) potential improvements to the OET. It should be noted that eight of our nine participants mostly gave extremely positive feedback about the OET. The remaining participant – the aforementioned deaf contributor - did not have such a positive experience of using the OET. This was largely because she felt that the OET was not inclusive of her needs and was too repetitive. The data from this participant works helpfully as a negative case, providing a viewpoint markedly different from the other eight.

3.1. Experience of Using the Tool

- The first five elements of our findings relate to participants’ experience of using the tool.

3.1.1. Facilitators to using the OET

- Since these participants had completed all 10 sessions of the OET, they were well situated to explain the elements that made it easier for them to return to the tool every week. Participants talked about external and internal factors which helped them come back to the tool every week. The external factors included a desire to help others or give back, wanting to contribute to research, or simply the tool itself being enjoyable and interesting. Interestingly, the quotations included in the OET from our interpretative phenomenological analysis interviews with earlier participants [5] caused one participant to say: I felt sort of an affiliation with the people that, you know, John would say, when I'm feeling down, that's ok, I know I've been through a lot and tomorrow's a better day. I got comfort from those little quotes that I was connecting with other people, that it wasn't like an isolated study. That there were other people out there who I've never met (laughs), I've never met anybody, can you believe that, with another bag. (P5) We can see here that these quotations encouraged P5 to keep coming back to the tool as they made her feel connected to others living with an ileostomy, none of whom she knew in real life. Internal facilitators included a desire not to be stigmatised, a determination not to quit a project once it had been started and the discovery that the OET helped boost mood. One participant described it as an opportunity to have his voice heard, saying: I thought it was a good opportunity for people like myself with stomas, just to talk about our experience. I mean, sometimes one reads things where we're being talked about. And I just thought it was good to give us the chance to use our own voices and say what our experiences were. (P2)In this way, we can see that the tool had the potential to empower participants and give them an opportunity to work with researchers, rather than just being the subject of research.

3.1.2. Barriers to Using the OET

- In addition to facilitators, participants discussed various barriers to using the OET. Once again, there were external and internal barriers. External barriers included time pressures, such as those arising from moving house: We've been in the process of moving house and whatnot, so logging onto the computer wasn't always forefront of the mind. We've been at our new house till 10 o'clock at night doing decorating and stuff, I wasn't gonna go home and even think about logging onto the computer (both laugh). (P5) P7, the participant who gave predominantly negative feedback about the OET, said: The same format again and again, the same thing over and again. BORING!!!!! (P7)This suggests that for some people, the format of the sessions was a barrier to completing the OET. Other barriers were more internal, such as finding motivation, being forgetful, or needing to be in the right mood: If I wasn't in the right kind of mood when I did it, […] if I was feeling stressed already, then it was a little bit more stressful. (P4)Hence we can see that there were a range of elements which may have made it harder for those who didn’t complete the OET to finish each session.

3.1.3. Successful Elements

- We asked our participants which parts of the OET were the most enjoyable and beneficial for them. The responses we got from eight of our nine participants were overwhelmingly positive and touched on a number of different individual sessions. In particular, the goals, life profile, mindfulness, quiz and video elements of the OET were very popular, with between four and six of the participants commenting on how much they enjoyed each of these elements. P5 gave a particularly noteworthy example of how well the goals had worked for her, saying: I've had fun and games getting medical care at the hospital, so one of my aims was to get that sorted? And do the chasing up I needed to get the appointment and not be on a long waiting list and I've done that now. […] And I'm just waiting for the new lot of medication to arrive. (P5)This gives a tangible example of a very beneficial goal that the OET helped this participant to attain – that of arranging correct treatment for the participant’s condition. Three of the eight participants commented on how much they enjoyed the fact that taking part in the OET made them feel like part of a group: It made me feel that I was part of something bigger. And that what I was saying was meaningful to somebody else, I suppose, that actually somebody was picking up on what I was saying. And the fact that other people were doing it, I suppose, as well. (P4)Given the online nature of the OET and the fact that no participants met each other at any point, this was an unexpected bonus of the tool.

3.1.4. Unsuccessful Elements

- We also asked our participants to tell us what didn’t work about the tool for them. Although the overall feeling was one of high satisfaction, there was still plenty of helpful feedback about what could be improved. In particular, between two and four participants commented on the gratitude letter exercise [17], the weekly pace of the sessions, exercises which had a lot of ‘homework’, and the videos as being less successful. Talking about the gratitude letter, P2 said: I think that's a sort of cultural thing, it's not that I don't express gratitude to people, it's just that I wouldn't do it in that way. […] I thought I really should be trying this, but then I thought no, I'm just not going to, it's not, I think, it felt to me foolish to make myself behave in a way that I wouldn't behave. (P2)Meanwhile, P8 talked about exercises in the OET which had a lot of homework, saying:I just didn't have time, I did maybe like a couple of days. But I certainly did not do that every single day. So for me, I found I got the learning from a day's worth of activates, I did two days on this occasion. But to me that was a little bit, I kind of glazed over a little bit (both laugh). (P8)This demonstrates that some participants may feel they have learnt enough from doing an exercise just once, in a short amount of time, rather than in a prolonged period, of the course of a week. It should be noted that while the gratitude letter and the videos didn’t work for some participants, there were two participants who said that the letter was a favourite element, and six who said that they enjoyed the videos. This suggests that it will always be difficult to write a tool in which every element works for every person, and adds justification to our decision to include 10 varied and diverse topics. Hopefully this meant there was something from which everyone could benefit.

3.1.5. Delivery of the OET

- Comments about the delivery largely split into two sections: points about the online format of the weekly sessions, and points about the accompanying diary that was emailed to participants in week one, in which they completed any written exercises and kept track of ongoing goals and so on. Participants were positive about the online sessions, reporting that they saved time and paper, and that the technology was easy and accessible. One participant said: If you wanted to nip and grab a cup of coffee while it's still up and that you could, I found that really good, you could do it at your own pace. (P6)This suggests that the online sessions allowed some participants a sense of autonomy around how and when they chose to take part in the sessions, arguably an advantage over a scheduled, weekly face to face group. Comments about the diary were less positive. Some participants experienced technical difficulties with the document, finding that they were unable to edit it on screen. Others felt overwhelmed by the size of the diary, which was 68 A4 pages, when they first printed it out:I wondered whether that would be better, being sent each week. (P3)This is helpful feedback which we could incorporate as we go forward with this work.

3.2. Impact of Using the Tool

- The next five elements related to the impact that the OET had on participants’ lives.

3.2.1. Existing Attitude to Ileostomy

- Seven of the participants talked about how they felt about their ileostomy before starting the tool. Some felt positively towards their stomas: I was happy with it beforehand. Yeah, so, I still get on very well and I manage and cope and try new things. (P1)In contrast, others described it as being a source of stress or distress before embarking on the OET: I was going through a really rough time with the stoma, and so it was quite opportune for me. […] Oo, I was having leaks once, twice a day, you know, from the bag, and it was knocking my confidence like mad, I could hardly leave the house. (P3)This range of experience is interesting as it demonstrates the fact that people with an ileostomy felt motivated to take part in and complete the OET whether they felt happy with the bag or not.

3.2.2. Impact of OET on Stress

- Since the two aims for the OET were reducing stress and boosting well-being, we specifically asked participants how they felt these elements had changed (if at all) since completing the tool. Seven of our nine participants reported that their stress levels – or their ways of dealing with stress – had improved since completing the OET:We've got some stressful bits at work at the moment coming up, so I do use this tool, I think, you know, just calm down. You know, I'll be in a meeting and think, think of the tool, calm down, just don't get wound up. (P6) I have an understanding that the stress has been caused by an irrational way of trying to control everything and I'm fearful when I don't have control. I know now not to be fearful when I don't have control (laughs). (P9) Of the two remaining participants, one said she didn’t feel she had stress to begin with. The other, P7, was the participant who had not had such a positive experience with the tool. She said:My stress levels were still the same only I have my own method of helping myself. (P7)We can see here that although the response was mostly extremely positive, there was one person for whom the tools didn’t help. However, on the whole these qualitative findings back up the highly significant statistics reported in our paper detailing the impact of the [7], suggesting that we were successful in reducing stress for people living with an ileostomy.

3.2.3. Impact of OET on Well-being

- We also asked participants directly about their mood following completion of the OET. Again, seven of the nine participants reported an improvement in well-being, while two reported no change. The findings here were again generally very positive and back up our quantitative findings [7], suggesting that we were successful in boosting well-being for people living with an ileostomy:I guess that goes back to mood, if you're more in control, then you don't feel helpless, then you feel like, you're not like a victim. (P8)It's very uplifting and it definitely improves your mood, definitely. Definitely improved my mood! (P9)

3.2.4. Impact of OET on Life with Ileostomy

- Participants were asked if they thought about their ileostomy and their lives with them in a different way since completing the OET. While two participants said they hadn’t changed the way they felt about life with an ileostomy, seven reported an improvement in the way they felt about it. Given that several of these participants had started off feeling quite accepting of the bag, this is unexpected and suggests that the OET may be helpful even to those who are not experiencing high levels of stress or distress around their stomas. Positive changes included dealing with practical issues around the bag, getting to know the stoma’s behaviour better, and feeling more accepting of the ileostomy. P1 said that she dealt with ‘hiccups’ caused by the stoma better since using the OET, giving an example of handling a suspected blockage by herself, rather than going into A&E as she had done previously:P1: I was almost at the point of going back to see the consultant to get him to do something, and I thought no, blow it, I'm going to manage. Int: What did you do to manage at that point? P1: Massage, hot water bottles, lying flat, and being a bit more patient.P9 felt that the tool eased her acceptance of her ileostomy:It definitely made me feel better, and that's a huge thing for somebody who has an ileostomy. It's a huge thing to (small laugh) be ok with it, be comfortable with it. (P9)Meanwhile, P2, who had had his ileostomy for 30 years and was already quite accepting of it said:This is just part of who I am. And the project kind of reinforced that in a way, in quite a positive way for me. I think it just, I'm trying not to use the word normalised, but I think that is the word I'm going to have to use. It normalised it a bit more. (P2)Again, this shows that the OET may be useful for people who have had stomas for a long time and are accepting of them, as well as for people who have recently had surgery, or those with high levels of stress and distress.

3.2.5. Lasting Impact of OET

- We asked participants if they felt they would continue to use the tools that they had learnt as part of the OET. Responses here were mixed: some felt positive about this, some were unsure, and one participant did not feel she would use the tools again. P6 felt optimistic about continuing to use mindfulness in the future, saying: Mindfulness is so big. And so yeah, I think I will be doing more of that in the future cos I think we'll be doing some stuff at work, so I'll take a keen interest in doing more for my own benefit as well. (P6)P9 gave a strong example of the ways in which she was putting the tool into practice and would continue to do so, saying of the life profile exercise: I found that very useful, because one thing I always wanted to do was do art? One of my things was to join an art class. And, I went and joined an art class! […] I'm really enjoying it. It's something that I had this burning desire to do for years and years. (P9)A couple of participants felt that while they intended to use the tool, they expected they may forget in time: When I remember, I think. I'm not yet at the stage where it's going to be automatic. […] I suspect it'll be the kind of thing that I use for a bit, and then I'll completely forget about, as life gets busy and you go back to normal and then something will trigger, and I'll suddenly go oh yes! And start using something again. (P5) Meanwhile P7, who had not enjoyed using the tool, did not feel that she would continue to use exercises, saying they were: Too boring and [with] not enough practical information. (P7)Despite this, findings were once again largely more positive than negative here.

3.3. Potential Improvements to the OET

- The final two elements of the framework refer to potential improvements or other uses of the tool suggested by participants.

3.3.1. Suggested Improvements to the OET

- Several participants suggested ways that we could improve the tool. Once again, there were some contradictory findings here, with one participant suggesting we use fewer videos and another saying that we should have a video in every session. It was also suggested that we could include some practical help on factors such as wardrobe following ileostomy surgery, and that it would be useful to make the tool available online for participants once they had completed it. Further suggestions from participants included: More broken up, less tell and more do. (P1) I found my study skills needed a bit of refreshing, I tended to lose papers, and the whole area of just organising myself to do it, I found difficult. I was getting there towards the end, but maybe something at the very beginning about how to organise yourself to do it. […] Yes, I think I would have added in a bit about study skills at the beginning. (P4)When is anyone going to do something about those who does not have hearing or sight and walking or what. Everything else is geared to the ordinary people who can hear, see and walk!!!!! (P7)P7’s comment here is especially beneficial for us as researchers; although we attempted to make the tool as inclusive as possible, there are obviously room for improvements, so it may be worth altering the tool for those with sensory impairments.

3.3.2. Potential Application of the OET in Other Areas

- While we did not ask the participants about this, five spoke about how the OET may be useful for other areas of life, rather than just ileostomy, or for people with other conditions as well as those that lead to stoma surgery. Again, this is an unexpected and positive finding. Five participants had other chronic conditions as well as the one that had led to their stoma surgery. Several commented on the fact that the tool helped them to cope with those conditions as well: I'm the age where I've got lots of chronic illnesses lurking around. And so I began to think about my approach to them or to the onset of new chronic illnesses, I think in a more positive way as a result of using this tool. So it's not only in terms of stoma care that I feel the benefit. It's in terms of other health issues as well. (P2) Meanwhile, it was suggested that the tool could be used in other areas as well as chronic health issues, with one participant saying: For me, I kind of used it for a relaxation kind of tool? Just to pick me up when I have negative experiences, mostly professional as well as some negatives personally. (P8)

4. Discussion

- We talked to nine participants who had completed our OET [7] about their experience of using the tool, any impact it had had on their lives and any potential improvements they could suggest for the tool. Feedback was overwhelming positive from eight of the nine participants. The ninth participant was more negative, feeling that the tool wasn’t relevant for her as a deaf person, and that it was too repetitive. Various scholars have suggested that using qualitative methods to evaluate interventions can be beneficial [8-14], and we believe that the findings of the current study illustrate this point.

4.1. Experience of using the OET

- Participants talked about facilitators and barriers for using the OET, successful and unsuccessful elements of it, and how they felt about the online format of the tool. Although online interventions avoid many of the issues that might cause participants to drop out of face to face interventions such as travel time, expenses, reluctance to seek help and so on [18], participants do still drop out [18]. Therefore, asking our participants about the facilitators and barriers to completing each weekly session of the OET is useful information that can be applied to future online interventions in order to try to help retention. Of the 62 people who started using the tool, 43 finished, meaning that we had a retention rate of 69.35%. While this can be considered a good retention rate [19], it would be useful to know how this figure could be improved on for future uses of the OET and other online interventions. Some of the facilitators for completing the tool discussed by our participants, such as a desire to contribute to research or a realisation that the tool is working have been found in other qualitative evaluations of online interventions [18]. Other facilitators such as feeling an affiliation with the people living with an ileostomy quoted in the OET or the chance to be heard are more novel findings. These findings emphasise the importance of using qualitative work to inform online interventions [8], and show that giving an intervention an interactive element can empower users and encourage them to stay engaged. Barriers to retention discussed by our participants included time pressures, an uninspiring format or forgetting to take part. These are barriers which have been found previously [18-19], and which emphasise the importance of managing participant expectations around how long completing sessions will take and sending timely reminders. As has been found in previous studies [19], there was some variation around which elements of the OET were successful and which were unsuccessful. As an example, six of our nine participants said that the videos were one of their favourite elements of the tool, whilst the other three said they didn’t like the videos at all. This demonstrates how important it is to have a range of elements available to participants in a tool like this, which will hopefully minimise the number of unattractive elements for individual participants [19]. We gave participants an opportunity to feed back about whether individual elements worked for them as they completed them, and reassured participants who hadn’t enjoyed a certain aspect of the OET that it was worthwhile to have tried it but that maybe the next exercise would work more successfully for them. Future researchers may wish to encompass a similar element in their interventions. Participants were also asked about the online element of the tool. Whilst the delivery of the sessions themselves was greatly positively, the diary which we sent participants, in which they could complete individual exercises, was received less well. We had had some technical difficulties with producing a document that would look the same and was editable on any device on which it was opened. Whilst the document we devised was usable by the majority of participants, some couldn’t edit it. Others who opted to print it out felt overwhelmed by the size of it. It would therefore be worthwhile for researchers contemplating a similar design to offer participants the chance to have the diary posted to them (something we offered participants, although none utilised this option), or to provide an online link once a week, rather than sending one large document in week one.

4.1.1. Impact of OET

- Participants talked about their existing attitudes to their ileostomy, the impact the tool had on their stress and well-being levels, as well as on their lives with the bag, and finally whether they felt the impact of the tool would last into the future. Our statistics revealed that the OET was successful in reducing stress and boosting well-being both on completion of the tool and at a three month follow up [7]. The largely positive qualitative findings in the current study back up these statistics. It has been posited that qualitative evaluations of interventions can answer several questions about the quantitative results, including understanding the reasons for the findings of the trial that tested the intervention [11]. In terms of exploring the reasons for our positive statistical results, we can see that many of our participants were able to describe taking control of stressors in their lives, meaning that stress levels were reduced as a result of better stress management, rather than stressors themselves being eliminated. We can also see that mood was boosted by a sense of control that the OET gave participants. In addition to this, several participants described feeling optimistic about continuing to use individual elements that they had learnt from the tool into the future weeks and months, with mindfulness and the life profile being two examples. In this way, our qualitative findings show that participants will pick out certain elements to continue, again backing up our decision to include a wide range of tools and exercises within the OET. It was an unexpected finding that the tool helped even those who felt happy with their ileostomy to adjust more fully to them. This is useful, nuanced evidence for the effectiveness of our OET.

4.1.2. Potential Improvements to the OET

- Qualitative evaluations of interventions can be useful as a way to determine improvements that can be made to those interventions [13]. That was the case in this study, in which participants suggested various improvements to our OET, such as providing more practical information or including a section on study skills. The data from our more negative participant, P7, went some way to explaining variations in the data for different participants [8] and can be used as a way to improve the OET [11]. This participant felt that the OET was not inclusive enough. This is helpful feedback for us, meaning that we can adapt the OET in future versions to consider people who have disabilities such as being deaf or blind. An unexpected finding was that several participants mentioned that the OET might be useful in other settings, such as for other chronic illnesses as well as the ones that may result in ileostomy surgery. Ileostomies are often treatments for older people, who may well have more than one chronic illness [12], so this could be a fruitful avenue to explore.

5. Conclusions and Limitations

- While we feel that this study is a valid and robust companion to our existing research [5-7] among patients with an ileostomy, it does have some limitations. Firstly, there is a selection bias in terms of who elected to take part in the study. It is likely that our participants were all highly motivated individuals, given that not only did they volunteer to take part in the OET and then complete all 10 weeks, but they also volunteered to then take part in a second study about their experiences. As such, their experiences of the tool and its lasting impact on their lives may differ from those of less motivated participants [11]. Although it would have been beneficial to speak to those participants who didn’t complete the OET, it was felt that it was unethical to approach those participants. Future researchers who are able to speak to those who drop out from interventions about the reasons for that will therefore be providing important data. Given the positive results elicited by our OET, it seems that future research testing its efficacy on larger groups of people living with an ileostomy is also warranted. Further, such interventions should also include a control group. Nevertheless, this study provides insight into the experiences of those who completed the 10-week training program, which will help improve upon the original OET.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This research was funded by the Ileostomy Association (grant number AD13/res), which was awarded to Adam R. Nicholls.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML