-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2017; 7(1): 1-9

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20170701.01

The Happy Consequences of Preservation Discipline: A Study in the Construct of and Socio-Demographic Variables of Discipline Designed to Preserve the Family

Shatha Jamil Khusaifan

King Abdulaziz University, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Shatha Jamil Khusaifan, King Abdulaziz University, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

PURPOSE: The purpose of this research is to investigate the impact of socio-demographic predictors (age, gender, monthly income, number of dependents, marital status, and level of education) on preservation disciplining (i.e. discipline designed to preserve the family unit as well as discipline the child) through the following six dimensions: 1. ‘child abuse became central concern’, 2. ‘rewarded for good things’, 3. ‘children should not hit each other’, 4. ‘most parents do not discipline enough’, 5. ‘need to explain the reason for avoiding an error many times’ and 6. ‘did nothing to overcome the problem’. METHOD: The research undertakes a survey based on a sample of 1751 children of 10 to 12 years of age across governorate of Assiut between May 2014 and December 2015. RESULTS: Findings show that dimensions 3, 4 and 5 have a significant influence on preservation disciplining and that these dimensions are all affected by the predictors of education, place of residence, age, and number of dependents (in the case of urban areas). CONCLUSION: If parents can be encouraged to discipline their children on the principles that children don’t hit each other in play or argument, that parents avoid physical discipline of their older children and that parents explain many times over the reasons for avoiding an error, they will be disciplining their children in a way that best develops self-discipline in their children and best preserves their family unit.

Keywords: Disciplining, Preservation, Socio-Demographic, Children, Parents

Cite this paper: Shatha Jamil Khusaifan, The Happy Consequences of Preservation Discipline: A Study in the Construct of and Socio-Demographic Variables of Discipline Designed to Preserve the Family, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 1-9. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20170701.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In general, parents need to apply appropriate strategies while rearing their children. Strict parenting, for instance, can cause more harm than good, such as negative psychological effects on children like low self-esteem. Children feel drawn towards their parents only if the parents learn to control their anger and use other parenting techniques instead. With child rearing a growing challenge for parents, a range of family preservation services is now available to provide guidance to and develop awareness among parents so as to prevent difficulties. Family preservation services strive to make family members aware of the positive influence they can have on their children which thus enhance the family’s unity. Specific services are available to alleviate the causes of crisis within families that lead to the removal of children from their homes, and range from anger management, counselling, the development of positive communication to parent training programs. Family preservation services are also necessary when families face crises in the form of a child’s physical or emotional setbacks. Most often though, these services are required by families whose children are in immediate need of out-of-home care, or whose children were placed in such care and are about to return to their families. The basic driver of family preservation services arises from the need to reduce the placement of children in foster care so that they can remain with their families, since it is their families who can be their greatest source of support, confidence and strength. Family preservation services also have the advantage of being less costly than foster care can thus lead to government savings. In America now for instance, it is almost compulsory for parents to take part in family preservation services if their children have become difficult to handle or are in the process of returning home from foster care. In the context of bringing up children, teaching discipline is a core element of parenting. However, parents often tend to mistake the maintenance of discipline with harsh punishment and control. The major requirement is to make an effective parenting framework within which children can learn discipline without feeling constrained by excessive parental control.The purpose of this paper is to show how disciplining with the intent of family preservation (‘preservation discipline’) can be a construct of the variables: ‘child abuse became central concern’, ‘rewarded for good things’, ‘children should not hit each other’, ‘most parents do not discipline enough’, ‘need to explain the reason for avoiding an error many times’ and ‘did nothing to overcome the problem’. The research also shows how socio-demographic variables like age, gender, number of children in family, marital status, educational level, monthly income, and residence affect preservation discipline.

2. Literature Review

- The idea in general that harsh discipline has no significant result based on the child’s gender has been substantiated by Parent et al. (2011) when they conducted a survey of 160 parents of 3 to 6 years old children. Another factor is parental marital status because it has been observed that single parents are less likely to use harsh means of disciplining than married parents. Past studies conducted by Bain, Boersma, & Chapman (1983) and Balcom (1998) proved that children with single parents exhibit poor academic performance in schools resulting in their completion of fewer school years compared to children with successfully married parents. Other research studies conducted by Downey (1994) or Kim (2004) have confirmed this assertion even after controlling for the effects of other variables such as economic and racial backgrounds of the parents. In these studies, it was found that married couples are more likely to enforce harsh discipline on their children. In rural areas, where most mothers are less educated, the rate of child abuse can be high, which is often a reflection of the mothers’ frustration levels as they find it difficult to rear their children with limited resources1. Other studies revealed that strict mothers establish less supportive relationships with their children (Burgess & Conger, 1978), more aggression during verbal or nonverbal interactions with their children (Bousha & Twentyman, 1984), and less interaction with their children (Schindler & Arkowitz, 1986) than non-abusive mothers. Although incidences of child abuse and neglect are common in families of any economic status, low parental income is seen to be a major influencing factor and children from poor families are more likely to experience neglect and severe violence than children from high income families (English, 1998). Regarding parental education, this current research says that parental education level plays a significant role in determining the harsh disciplining of children. More educated the parents are less likely to use harsh disciplinary means, and are also more likely to understand the utility of coaching effectively and internalizing discipline rather than externalizing it. Chevalier et al. (2013) suggested that parents with higher levels of education stress the same for their children, thus, do not resort to harsh disciplinary means. Chevalier et al. observed that daughters of educated parents ewere more likely to remain in education than daughters of non-educated parents.The degree to which using physical discipline as a means of tackling children’s disciplinary problems has been a matter of debate. Lawrence and Smith (2008) studied the role of professionals in creating awareness by communicating with parents about child disciplinary practices. These authors explored the nature of the professionals’ function which included knowledge of potential legal implications and the ability to perform their designated duties. Based on a study of 58 participants, 48 of which were parents, it was found that striking in order to teach discipline was considered a normal form of punishment. However, responses from social worker participants revealed that families often sought advice from them, thus implying the significance of their contribution in creating awareness among parents about alternatives to physical punishment. The authors suggested that with high-impact information from well trained professionals it is possible to alter general perceptions regarding the use of violence against children. Aggressive parents using violence actually create a social problem when children use violence against them in turn. Ibabe (2015) studied the role of family relations in relation to the behavioural patterns of children with their peers. This author studied 585 children between the ages of 12 and 18 to understand the presence or absence of violence in their social behaviours. It was concluded that while parents who use communication skills to deal with children tend to produce non-aggressive children, parents who use physical violence or rigid disciplinary actions tend to produce aggressive children exhibiting both physical and psychological violence. The author emphasized the development of parental awareness through appropriate parental education and training.The impact of physical violence of children can be a result of the concerned child’s perception of fairness. Evans, Galyer and Smith (2001) studied 60 girls and 50 boys between the ages of 9 and 11 and focussed on their responses to unfair experiences. The result revealed that there was a gender based perception of the difference between receiving an undeserved punishment and not receiving a deserved award. While not receiving a deserved award is considered unfair by boys it results in them feeling more unworthy than if they had been unfairly punished. On the other hand, receiving an undeserved punishment was considered unfair by girls. One interesting thing that was discovered in this study is the explanation that children offer for their social judgements of these situations. It often happens that when one child is being unduly punished another sibling might feel guilty since he or she may feel responsible for the misdemeanour that called for the punishment. The authors explained that this happens mostly because parents have a tendency to consider older children responsible for the actions of their younger siblings. Research has found that using physical violence as a means of disciplining children is viewed differently by parents from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. In this context, Hom, Cheng and Joseph (date) studied 175 parents in high, middle and low socioeconomic backgrounds. Although they found that socioeconomic status does not had a significant role in disciplinary beliefs, spanking children for misbehaviour was more common among the parents from low socioeconomic backgrounds. The authors associated this with parental educational levels thus indicating that use of physical violence on children is indirectly related to their educational level. It was also observed that parents from high to middle socioeconomic backgrounds placed more emphasis on rewards than punishment to induce discipline among their children. The authors explained this in terms of these parents having more resources available to provide for their children than parents from low socioeconomic background.As part of teaching and maintaining discipline in children parents often resort to providing them rewards for good or improved conduct, or threatening them with punishment if they fail to improve. Greitemeyer and Kazemi (2008) found that children responded positively when they were promised a reward compared to children who were threatened with punishment. Moreover, since parents are informed by educators that rewards have more long lasting effects on children most parents are generally inclined toward rewarding their children, however, it has been observed that parents use rewards without strongly believing in their positive impacts, so it is likely that many parents will not stick to using rewards over punishment in the long run. The kind of child discipline measures used by a parent is often dependent on the parent’s gender. In this context, a survey by Shek (2005) showed that participants perceived their mothers as having more behavioural control with respect to discipline and monitoring of them, while fathers have more psychological control. This finding calls into question the general perception that mothers are less aggressive parents. The result also challenges the observation made by Collins and Russell (1991) that the mother – child relationship is filled with more warmth than the father – child relationship. According to the authors this is because fathers are more inclined to display firmness with children. Shek (2005) also explained that mothers may have a more positive influence over their children than fathers because mothers spend more time with children than fathers.DiLillo & Damashek (2003) noted that parents with a background of childhood sexual abuse may find it difficult to establish a normal relationship with their children. Parents with a history of childhood abuse react more strongly when their children go through similar experiences to theirs, rather than parents who have no such history (Deblinger et al., 1994; Coohey & Braun, 1997). The highest probability that mothers will physically abuse their children occurs with women who suffered at the hands of their own mothers during their childhood (Pears and Capaldi 2001). In order to determine the differentiating factors between families with child abuse and without child abuse, Oates et al. (1980) compared 56 families having child abuse with a control group of families without it. It was found that several factors contribute to child abuse at the hands of parents: unplanned pregnancies which result in lack of preparation for becoming parents; high expectations of children which cause parents to become abusive if their children tend to get into trouble more often than children from other families. There can also be reasons like financial difficulties in the family, or parents having concerns about their own health issues which may cause parents to vent their frustrations on their children.The literature studied does not consider the specific governorate of Assiut in exploring the dimensions of preservation discipline, i.e. discipline that preserves the family unit. In fact, dimensions of preservation discipline have not been adequately explored or studied at all so far. The present research establishes this dimension through the various factors which construct it, and looks at the impact of external parameters, such as socio-demographic factors, on the dimension of discipline.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Approach

- The present research uses a positivist approach because the analysis is quantitative in nature. The study considers a sample of 1751 children of 10 to 12 years across Assiut. As children’s motor skills might take around 8 years from birth to develop, during this period parenting is significant. Disciplining obviously comes along with parenting (Kyle, 2008). Hence reports received from children between 10 to 12 years of age should be able to capture best the information about their experience of being disciplined. A 23-item questionnaire was distributed to all the children (including male and female) by randomly selecting the sample and was answered during face-to-face interactions. Both open-ended and close-ended questions were used. The quantitative method includes exploratory and confirmatory analysis. Most of the items were structured as per the Likert scale of 1 to 5. Amos software was used for the statistical analysis. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) with path diagram models was used, and hence the goodness of fit tests was estimated for the SEM.

3.2. Instrument: Reliability, Validity and Factor Extraction

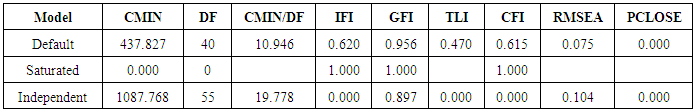

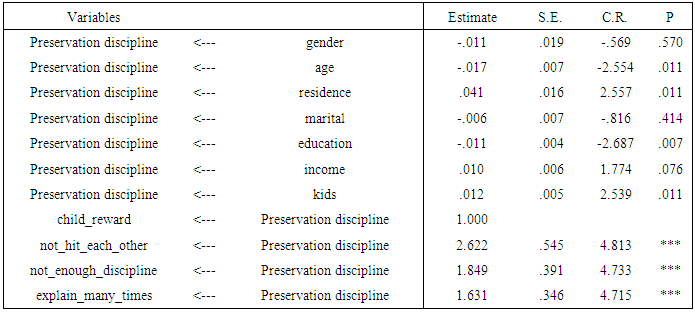

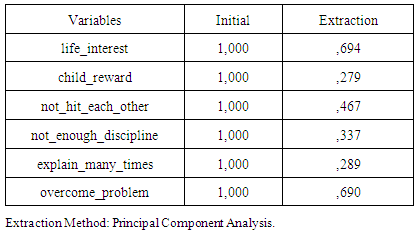

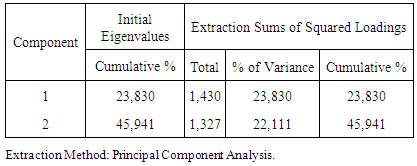

- The reliability of the questionnaire was measured by KMO, Bartlett’s test. Disciplining with prevention as a construct of the following observed variables was tested: ‘child abuse became central concern’, ‘rewarded for good’, ‘children should not hit each other’, ‘most parents do not discipline enough’, ‘need to explain the reason for avoiding an error many times’ and ‘did nothing to overcome the problem’. First, the suitability of a factor analysis was tested via KMO, Bartlett’s test. The closer the values of the KMO test to 1, the better, so the obtained result of 0.518 shows moderate suitability. The sphericity assumption holds since Bartlett’s test is significant at the 5% level. Therefore, the factor analysis can continue. From the communalities table (See appendix 1) it is evident that ‘child reward’ and ‘explain many times’ have low shared variance. The remaining variables have moderate levels of shared variance. Following a further look at the extracted factors table (See appendix 2) two factors were extracted which were associated with the variables included in the dimension. The criterion for extraction is an Eigenvalue higher than 1. The first factor explains 23.8% of the variance and the second 22.1%. The component matrix shows the loadings of the variables by each of the two extracted factors. “Overcome problem” and “life interest” were once again loaded high in the first factor. The remaining variables were loaded moderately in the second factor. As a conclusion from the analysis of the proposed dimensions of child abuse sample questionnaire out puts , two factors will be further explored with regard to all six of the proposed six variables: Factor 1:‘overcome problem’ ‘major focus’; Factor 2: ‘child reward’, ‘not hit each other’, ‘not enough discipline’, and ‘explain many times’ (See Glossary).

4. Predictive Factors

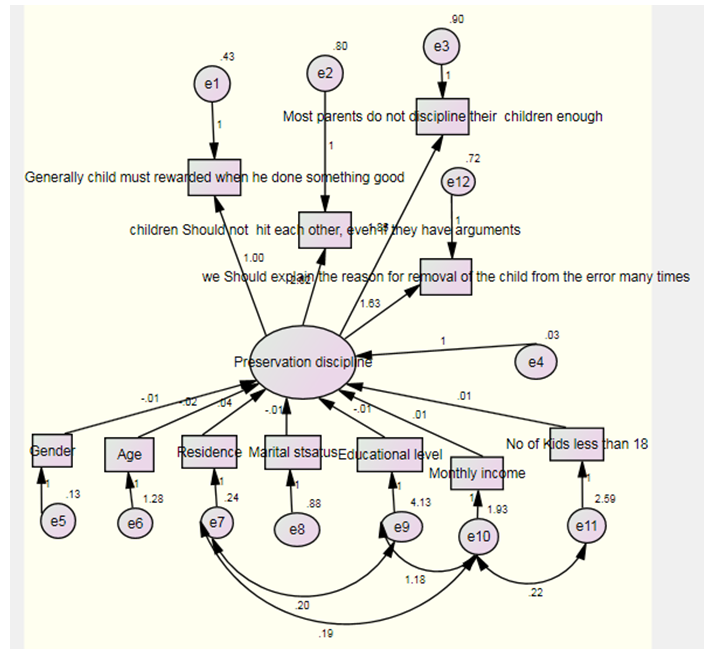

- It is important to test for a predictor or an independent variable which can statistically and significantly influence the dependent variable of harshly disciplining children. This involved two steps. Firstly, the dependent variable ‘self-esteem’ was extracted and evaluated according to its six determinant variables using EFA. The six variables which construct self-esteem were identified and grouped into two factors: Factor 1 – ‘overcome problem’ and ‘major focus’; Factor 2 – ‘child reward’, ‘not hit each other’, ‘not enough discipline’, and ‘explain many times’. Secondly, a structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis was carried out for the dependent variable (preservation_disciplining) to illustrate its association with the various independent socio demographic variables (age, gender, residence, parental marital status, parental educational level, monthly income of family, and number of children less than 18 years).

5. Limitation and Future Scope of Research

- The main limitation is the time frame taken which might not be applicable five years hence. Secondly, the results for Assiut might not be generalizable for other countries. It would be very useful if the paper initiated future research of the same sort in other nations, especially western nations, and comparative analyses were carried out between western and non-western nations on the same ground.It would also be very useful for follow-up research to be conducted in 5 to 10 years time to check on the effectiveness of programs run by preservation agencies that have aimed to teach their clientele how to use preservation discipline with their children.

6. Findings and Discussion

- The results obtained by CFA in Amos for the first two hypotheses are presented below in a path diagram and SEM Table 1 and Figure 1.

|

| Figure 1. Path Diagram for the six dimensions and relations with socio-demographic variables |

|

7. Conclusions

- Results of this study support the assertion that the constructs most important for disciplining children with preservation are: children should not be allowed to hit each other in either play or argument; mothers do not discipline their children enough and children need an explanation several times to prevent them from committing an error. Consequently, we now know that when we see mothers are not disciplining their children too much, that when children are not allowed to hit each other while playing or arguing, and that when children are repeatedly being given verbal explanations about their mistakes to prevent them from committing them again, we seeing disciplining with preservation at work already. These three observed variables are significant outcomes of disciplining with preservation. They lead to positive parenting with the right mix of disciplinary measures that can increase self-confidence among children. They produce disciplined children who are well mannered and display appropriate behaviors in all circumstances. They allow parents to teach their children about the different outcomes for bad and good behavior so that their children can make suitable choices for themselves.This study’s findings also indicate that discipline tends to be more effective with younger children. This finding seems to suggest thatuse of appropriuate discipline stategeis with younger children teaches tham aboutappropriate behaviotr earlier in thir lives, thus reducing the need for basic discipline when they are older, has confirmed too that older children are in less need of discipline since education creates awareness. They are best influenced when verbal discipline is used such as telling them in a clear manner the consequences of their actions.

8. Practical and Policy Implications for this Paper

- The use of preservation discipline makes stricter disciplining unnecessary, and in fact, preservation discipline potentially offers a way out of the current prevalence of harsh disciplining and abuse of children. This will be an implication of great moment to preservation agencies. They can now ensure that their parents learn how to “use” the three observed variables to the advantage of themselves and their children. By doing so, they will be encouraging parents to behave in ways that allow their children develop self-discipline which also reinforce the family’s unity - which of course is beneficial for all.

9. Glossary

- Harsh discipline:1. Corporal punishment is often used by parents as a disciplinary tool.2. Child reward:Generally child must rewarded when he done something good.3. Not hit each other:Children should not hit each other, even if they have arguments.4. Not enough discipline:Most parents do not discipline their children enough.5. Explain many times:Parents should explain the reason for removal of the child from the error many times.6. Overcome the problem:Has you done anything to overcome the problem of child abuse?

Note

- 1. This study was supported by the office of child development Grant 90-C-445, and was presented at the 1977 Biennial Meeting of the society for research in child development, New Orleans Louisiana.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML