-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2016; 6(6): 163-170

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20160606.01

Association of Violence with Anxiety and Depression among Iraqi Junior Doctors

Riyadh K. Lafta 1, Saba Dhiaa 2, Waleed A. Tawfeeq 3, Ameel F. Al-Shawi 3

1Affiliate Prof., University of Washington, Seattle, USA

2Coll. of Health & Medical Technologies, Baghdad, Iraq

3College of Medicine, Mustansiriya University, Iraq

Correspondence to: Saba Dhiaa , Coll. of Health & Medical Technologies, Baghdad, Iraq.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

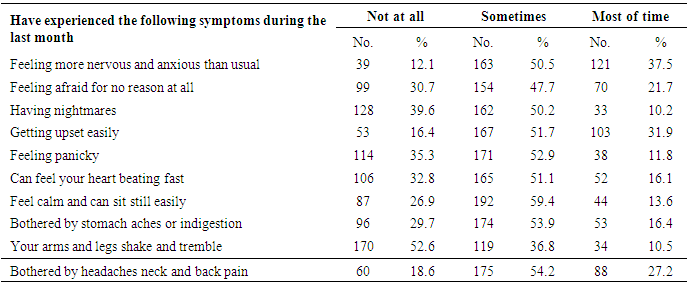

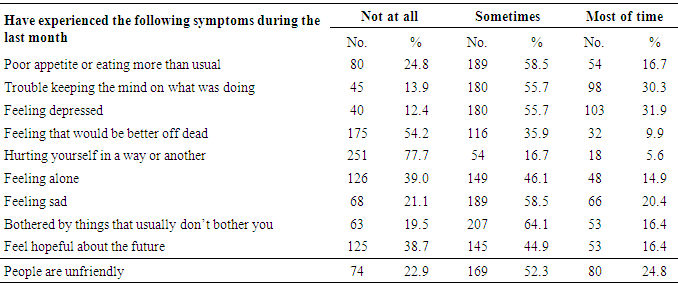

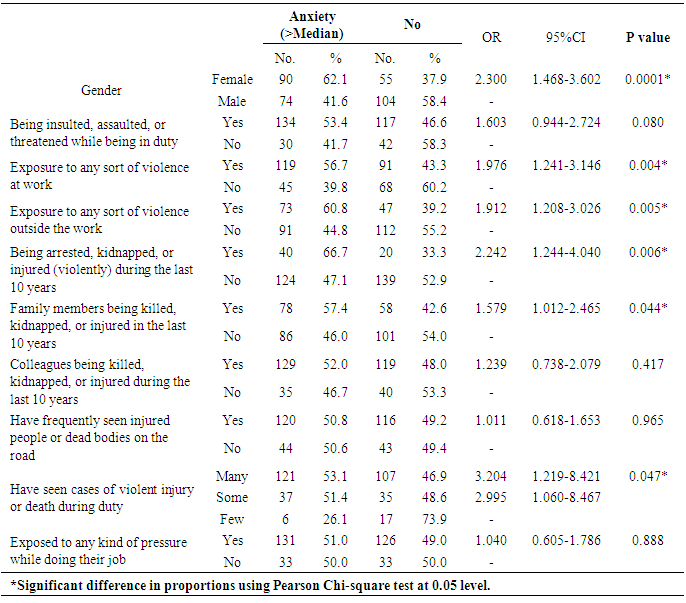

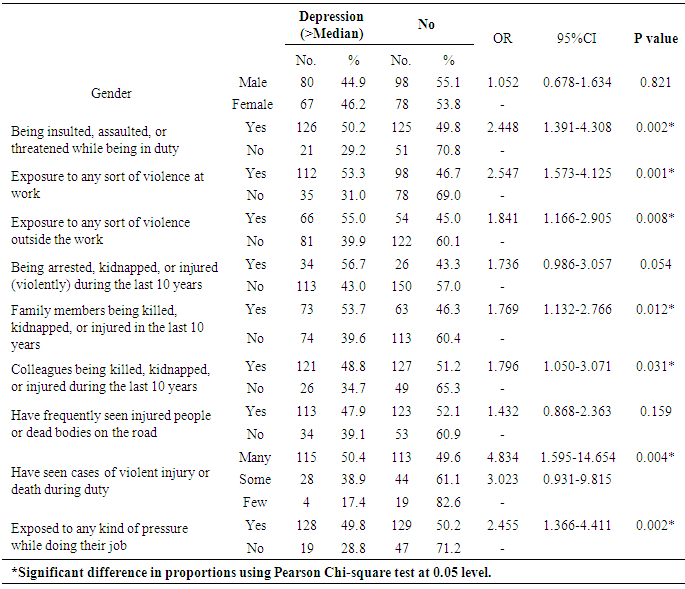

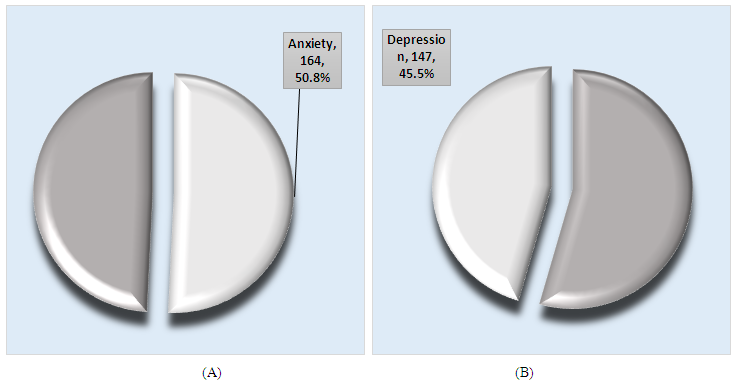

Background: Doctors are not protected to the occurrence and consequences of mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, and occupational burnout, likely owing to their exposure to high levels of occupational stress. Methods: Written questionnaires were completed by 323 junior resident doctors from 20 teaching Hospitals in Baghdad city. The questionnaire inquired about exposure to any sort of violence, and the presence of any psychological symptoms that may refer to anxiety or depression. The questions were borrowed from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Findings: More than one half of the doctors (164, 50.8%) reported the presence of anxiety symptoms, and 147 (45.5%) reported depressive symptoms. There was a significant association between exposure to any sort of violence at work (OR= 1.976, p <.005) or outside the work (OR= 1.912, p < .005), and reporting anxiety symptoms. The odds ratio of exposure to arrest, kidnapping or intentional injury was 2.242 (p .006). A significant association was also found between reporting depressive symptoms and exposure to violence at the work (OR=2.547, p =.002) or outside the work (OR=1.841, p =.008), and with history of killing, kidnapping or injury of family members (OR= 1.769, p .012) or colleagues (OR= 1.796, p .031). Exposure to pressure during work was also significantly associated with depressive symptoms (OR=2.455, p .002). Interpretation: The unsafe situation in Iraq has led to a high prevalence of anxiety and depression among junior doctors, Special efforts are needed to insure psychological support, and rehabilitation programs for this “vulnerable” group.

Keywords: Anxiety, Depression, Iraq, Junior, Doctors

Cite this paper: Riyadh K. Lafta , Saba Dhiaa , Waleed A. Tawfeeq , Ameel F. Al-Shawi , Association of Violence with Anxiety and Depression among Iraqi Junior Doctors, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 6 No. 6, 2016, pp. 163-170. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20160606.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- As Human beings, doctors are not protected to the occurrence and consequences of psychological illnesses. [1] Doctors (especially junior residents) face particular challenges such as high patients’ attendance, long duty hours, repetitive exposure to traumatic events, potentially violent situations, and critical decision-making that place them at more risk of anxiety, depression and other stress related psychosocial problems. [2]Physicians are vulnerable to some mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, and occupational burnout, likely owing to their exposure to high levels of occupational stress. [3] Many researches demonstrated that one-fourth to one-third of residents will be clinically depressed at some point in their training. [4-6]A study in USA revealed that the prevalence of depression in resident physicians is higher than that of the general population, and is associated with physical health, an unhappy childhood, and stress at work. [7] Although the actual incidence of anxiety and depression in medical doctors is unknown, many studies on medical students in developing countries like Saudi Arabia and Pakistan reported 47% to 73% prevalence of anxiety and depression. [8-10]The literature revealed that exposure to violence may lead to abnormal neurological changes that can cause malfunction of the limbic system of the brain especially in cases of long periods of exposure to trauma, particularly when the exposure occurred at childhood. [11] Such trauma usually causes adverse psychological effects that may last for a very long time, may interfere with their capability, and inversely reflected on their performance regarding the health care services they are affording. Several studies have evaluated the mental health of doctors in developed countries and indicated that the prevalence of depressive symptoms among physicians ranged from 10% to 15% in the US, Britain, Norway, and Japan. [12-15] A recent Dutch investigation concluded that anxiety and depressive symptoms were prevalent in 24% and 29% of physicians, respectively. [16] Researchers in China focused on anxiety and depressive symptoms among physicians and concluded that the prevalence of depression ranged between 31.7%, and 65.3%. [17-19] In United Kingdom; about half of the senior medical staff suffer from high levels of stress and anxiety, and half of the junior doctors are suffering from emotional disturbance. [20] Poor psychological health amongst doctors negatively affects the quantitative and qualitative care of patient, leading to poor performance and affects patient's satisfaction, and adherence to treatment, [21] moreover, it may have serious consequences on the wellbeing of the whole community. [22] Up to 100, 000 patients in USA die each year because of preventable unpleasant measures The stress of medical resident training, including lack of sleep and leisure time, are among the most commonly cited reasons for such errors. [23] Residents who are depressed are about six times more likely to make medication errors than those who are not depressed. [24]Iraqi doctors represent a unique group, they have been exposed to successive shots of intolerable stress, making them the most vulnerable group among all doctors globally, knowing that Iraq has been labeled as the most dangerous country in the world. Doctors in Iraq are not only lacking sleep or leisure time, they are living in panic through being continuously at risk of assassination, kidnapping, threats, and forced displacement which became part of everyday life in Iraq. The rate of violent events among Iraqi specialist doctors during 2004-2007 was estimated to be 3.7%, and the rate of violent death at 1.6%. [25] This stress continuous stress has pushed many of them to flee during the past years seeking asylum in other countries [26] resulting in a severe shortage in workforce and quality of health services, and added more burden on the (already limping) health system. Rationale of the study: Anxiety and depression symptoms are important to assess especially among medical doctors as they have a sensitive job that deals with human life. Raised levels of anxiety and depression among resident doctors can lead to physical and emotional ailments, poor performance, absenteeism and negativity in terms of attitudes and behavior. [27] It is also associated with medical errors, decreased ability to handle work-related stress, discontinuation of medical training, disruption in personal lives, and suicide. [7]The objective of this study was to explore the prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in a sample of Iraqi junior doctors living in Baghdad city in an attempt to understand the pressure that the junior doctors are exposed to.

2. Methods

- This cross sectional study was conducted in 20 major and teaching hospitals in Baghdad city during the period from July through August 2016. A convenient non probability sample of junior doctors was chosen, those were either newly graduated or candidates of postgraduate studies working as rotators or permanent residents in the surveyed hospitals.The first part of the questionnaire was developed by the researchers and enquired about the exposure of doctors to any sort of violence including exposure to insults, assaults, threats, arrest, kidnapping or being intentionally injured. Also exposure of their colleagues or family members to any sort of violence (killed, kidnapped or injured), and whether any of their seniors or colleagues have left the country to escape the risk of violence, whether they have frequently seen bodies or injured people on the road, and whether they are exposing to any notable pressure in their job. The second part of the questionnaire was about the presence of any psychological symptoms that may refer to anxiety or depression (ten items for each) in those doctors. The questions related to depression were borrowed from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), [28, 29] they included the respondent’s feelings during the last month, responses ranged from (not at all, sometimes or most of the time). The likelihood of having anxiety or depression was set when the score is above the median (more than 10). We did not attempt to diagnose these diseases, but we, rather, classified those doctors as having “probable” anxiety or depression on symptomatic basis.

2.1. Ethical Issue

- The self- administered questionnaire form was anonymous. A verbal consent was taken from all the respondents after explaining to them the purpose of the study, giving them the full choice to participate, and assuring them that all the information will be kept strictly confidential and will not be used for any purpose other than research work. The questionnaire was validated and approved by the Ethics Committee at the College of Medicine/ Mustansiriya University.

2.2. ADAS Calculation

- The calculation of anxiety and depression scores was done as follows: the 10 items of anxiety questions were coded as not at all, sometimes, and most of the time, each item was scored (0 to 2), with higher scores indicating most of the time. For each person, a total score of more than 10 (median) indicates significant anxiety symptoms. [30] The same was applied for depression questions.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- Analysis of data was carried out using the available statistical package of SPSS-22 (Statistical Packages for Social Sciences- version 22). Data was presented in simple measures of frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation, and range. The significance of association of different percentages (qualitative data) was tested using Pearson Chi-square test (χ2-test) with application of Yate's correction or Fisher Exact test when indicated. Statistical significance was considered whenever the P value is equal or less than 0.05.The odds ratio (OR) as a measure of association between an exposure and an outcome was calculated. Odds ratio is most commonly used in case-control studies, however it can also be used (with some modifications and/or assumptions) in cross-sectional and cohort study designs.

3. Results

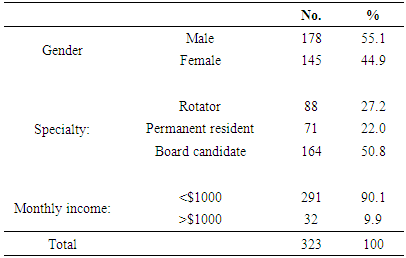

- Of the 400 forms that were distributed; 323 were collected giving a response rate of 81%. The junior doctors’ age ranged from 24-39 (mean 29.5 ± 3.8), with 55.1% males and 44.9% females, half of the sample (50.8%) was postgraduate (Board) candidates, 27.2% rotators and 22% were permanent residents, more than 90% of the doctors reported a monthly income of less than $1000. See table 1.

|

|

|

|

| Figure 1. Prevalence of Anxiety (A) and for Depression (B) among the study sample |

|

|

4. Discussion

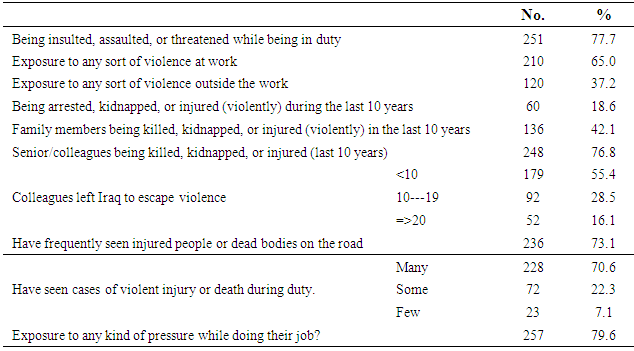

- The 323 junior doctors from 20 major and teaching hospitals in our study aged between 24-39 years, which means that they grew up under high stress during the period of unrest that the Iraqis were experiencing in the eighties and nineties (including the Iraq-Iran-war, the first Gulf war and the economic sanction), [31, 32] during which the cohort of Iraqi children and youth (some of whom are now included in our study) have been subjected to dire conditions, they were facing very real dangers of disease, starvation, psychological trauma and death, [33] such conditions make people less resilient to adverse experiences later in their life. The prevalence of “probable” anxiety was shown to be 50.8%, which means that more than half of the resident doctors were experiencing symptoms of anxiety; likewise, the prevalence of “probable” depression was shown to be 45.5%. This prevalence is remarkably higher than that in the general population. WHO reported (in the Iraqi Mental Health survey) that the prevalence of anxiety in the general population was 13.8% and of depression was 7.2%, [34] while in a previous study conducted in Baghdad; the prevalence of probable depression among health care providers was found to be 66.5%. [35] This indicates that the high prevalence among junior doctors is not just part of the general unstable condition in the country, but that there is an additional pressure on this stratum that makes the problem an issue. The comparison of our findings with other countries revealed that it is way higher than the results of a study in USA which showed a prevalence of depression among health practitioners of only 9.6%, [36] while another study in Orlando/Florida revealed a prevalence of depression of 7% for mild and 5% for moderate to severe scoring. [37] Our results were also higher than those in the regional countries; in Pakistan, the prevalence of anxiety and depression in resident doctors was 27.3%, [38] in Nigeria the prevalence of depression was 17.3% in resident doctors and 1.3% in non-resident doctors with no gender significant variations, [39] and in Turkey, the prevalence of probable depression among 156 resident doctors was found to be 16%, more in females. [40] While our results were close to the findings in some Arab countries like UAE where the reported prevalence of anxiety and depression was 57.4% and 63.3% respectively although these countries are considered stable in comparison to Iraq. [41]Female doctors showed a more tendency to have anxiety symptoms than males; this finding is consistent with other articles which suggested that females are more vulnerable to develop mental disorders when exposed to traumatic events. [42]As Iraq now tops the most dangerous countries in the world, we dealt with anxiety and depression from the angle of its relation to violence. Since the USA invasion in 2003, the Iraqi academics (and doctors in particular) continued to face intolerable levels of violence and systematic targeting. [43] they are exposed continuously to assassination, kidnapping, threats, and humiliation. [26]About two thirds of the sampled doctors reported exposure to different forms of violence, and about one fifth of them were exposed to either arrest, kidnapping or intentional injuries. The results of the current study revealed a statistically significant association between depression symptoms and exposure to violence during duty and with frequent seeing and dealing with cases of violent injury/death during duty. Several articles confirmed that doctors exposed to high stressful conditions especially those working in the emergency units and in times of wars are more susceptible to develop mental disorders. [43-45]

5. Limitations

- As anxiety and depression could be multifactorial; the effect of confounders (personality, family history of psychological problems, threshold of stress) couldn’t be evaluated, however, we did not attempt to diagnose these diseases but we, rather, classified the respondents as having “probable” anxiety or depression on symptomatic basis.

6. Conclusions

- The study revealed a high prevalence of anxiety and depression among junior doctors, that might be due to the high pressure they are exposing to in their job, their daily living with high risk, and their gloomy future. Special efforts are needed to insure psychological support for those doctors through special sessions of residency counseling, assurance, rehabilitation programs, and providing security protection for them at least at the work during doing their job.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML