-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2016; 6(4): 85-93

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20160604.02

A Theoritical Model of Theory of Mind and Pretend Play

Dewi Retno Suminar1, Th. Dicky Hastjarjo2

1Faculty of psychology, Airlangga University, Indonesia

2Faculty of psychology, Gadjah Mada University, Indonesia

Correspondence to: Dewi Retno Suminar, Faculty of psychology, Airlangga University, Indonesia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study aims to test the theoretical model is formed, ie, whether the pretend play is influenced by age, gender, socio-economic background of parents of children, and theory of mind. Subjects were 51 boys and girls aged 36-84 months from a variety background of socio-economic status. Data was collected through observation of the child during play, which is performed by four assessors. Reliability and Inter-rater reliability coefficient was 0.913. Pretend play tool used has been test by 7 professional appraiser, namely, kindergarten teacher and preschool teacher. Content Validity Index (CVI) observation instrument pretend play CVI instruments is 0.351 and Theory of Mind is 0, 323. Data on age, sex and socioeconomic status was obtained through the identity of the children. Analyses were performed using variance-based SEM methods, namely the Partial Least Square (PLS). Overall evaluation of the model shows that all the variables or constructs have built compatibility between models and empirical models. ToM and age significantly affected the pretend play, while gender and parental income did not significantly influence the pretend play. ToM and age did not have a significant relationship. ToM influenced the pretend play in the high category, whereas the effect of age on the pretend play was in the medium category.

Keywords: Theory of mind (ToM), Pretend play, Theoretical model

Cite this paper: Dewi Retno Suminar, Th. Dicky Hastjarjo, A Theoritical Model of Theory of Mind and Pretend Play, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 6 No. 4, 2016, pp. 85-93. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20160604.02.

Article Outline

1. Background/Objective and Goal

- Playing is fun and done for its own sake (Doherty, 2009; Lang, 2007; Santrock, 2004; Scarlett, Naudeau, Paternak, & Ponte, 2005; Willburn, 2000). Through play, children will be affiliated with peers, to escape from stress, stimulate cognitive development, develop exploration, and able to detect potential hazards. Playing is a form of readiness future (Santrock, 2004; Scarlett, Naudeau, Paternak, & Ponte, 2005; Sutton Smith, 1978). Playing has a good function for the physical, emotional, and social cognition. This makes the kids play without prompting, and do it gladly and repeatedly, thus allowing stimulation in child development (Gullo, 2005).Ideally, stimulation play is able to develop all aspects of development. But in fact, the toys that rely on technology make the children more individual. Children use playing to build meaning and explore the environment to obtain a lot of information (Carlson, Taylor, & Levin, 1998; Goncu, Mistry & Mosier, 2000; Pillemer, & White, 2005; Santrock, 2004; Willburn, 2000). However, if there is lack of playground equipment that allows children to explore the environment, it is difficult for children to develop optimally. Each type of play will give different effects for children (Auerbach, 2004; Lee, 2008; Scarlett, Naudeau, Paternak, & Ponte, 2005). Children's play can provide stimulation for the development of cognitive, affective, and psychomotor (Berns, 2010; Chudachoff, 2007; Gullo, 2005; Santrock, 2004; Scarlett, Naudeau, Paternak, & Ponte, 2005; Sheridan, 1999; Suminar 2006). At the same time, play can also provide stimulation in some aspects of child development. One type of them is a play that makes the child is capable to symbolize the things and develops their imagination. It is called pretend play (Russ, 2004).Role in the process of pretend play makes symbolization and imaginative process that they behave "as if" doing something in play (Doherty, 2009; Fein, 1981; Leong, 2003; Kavanaugh, 2006; Russ, 2004; Scarlett, Naudeau, Paternak, & Ponte, 2005; Wilburn, 2000). Given two processes, symbolic play and imaginary terms are used as the definition of pretend play. According to Doherty (2009) and Wilburn (2000), one of the elements of the symbolic and the imaginary play is a child's ability to represent the tools used in the play. In the pretend play, children interpret the tools used to play (cognitive aspect). Children also begin to engage, move from one role to another, and make them understand how their feeling is while performing the role (affective aspect) in play. While it performs by groups of children, they will interact with other children (interpersonal aspects). During the pretend play, children may experience tensions and conflicts with other children but it will bring up the ways to overcome in order to solve the problem (problem solving). These four aspects can be encountered when the children perform pretend play (Doherty, 2009; Keskin, 2008; Russ, 2004).Pretend play is influenced by socio-economic background and life experience (Carlson, Taylor, & Levin, 1998; Doherty, 2009; Goncu, Mistry and Mosier 2000; Goso, Morais & Otta, 2007; Kreppner, O'Connor, Dunn, & Anderson-Wood, 1999; Mascolo & Bhatia, 2002; Santrock, 2004; Sobel & Lillard, 2001). The child’s gender will affect the selection of games in the pretend play (Fein, 1981; Papalia, 2008; Scarlett, Naudeau, Paternak, & Ponte, 2005; Sluss & Stremmel, 2004; Suizzo & Bornstein, 2006). The child’s age has effects on the pretend play. The child who hard to pretend will find the difficulty to perform the pretend play (Anderson, 2005; Kavanaugh, 2006; Nielsen & Dissanayake, 2004; Sheridan, 1999).From this playing process, it will appear the mind which is associated to the cognitive processes (Lillard, 1998). Theory of mind or ToM is a child's ability to understand human behavior (Astington & Barrlault, 2001). ToM refers to the ability to represent, conceptualize and explain the reason of self mental states and other. It also refers to a person's ability to see the reason and make the conclusion about the others mental states (Clifford, & Stein, 2006; Keenan, 2003; Kobayashi, 2009; Keskin, 2008; Kreppner, O'Connor, Dunn, & Anderson-Wood, 1999; Male, 2001; Wellman, 2011). ToM reflects the capacity to interpret what others saying, to feel the others behaviour, and to predict what people will do (Clifford & Stein, 2006).Several studies Astington & Barrlault, 2001; Doherty, 2009; Keskin, 2008; Sobel & Lillard, 2001 and Ritblatt, 2000, showed the relationship between the pretend play with ToM. The ToM differences would appear while the children were performing pretend play. According to Bergen, 2002; Berguno & Bowler, 2004; Keskin, 2008, Lewis & Ramsay, 2004, and Saracho 2014, the relationship between the pretend play with ToM could be described through mental representation process.Based on those descriptions, this study will prove whether the theoretical model constructed from variables of theory of mind, gender, age, socioeconomic status and pretend play can be demonstrated as a good theoretical model. Therefore, the formulation of issues is: whether Theory of mind, gender, age and socio-economic background influence the pretend play consisting of several aspects i.e. cognition, affection, interpersonal and problem solving. Thus the objective of this research is to develop and examine the theoretical model empirically related to the influences of theory of mind, gender, age and socio-economic background on the pretend play.

2. Methods

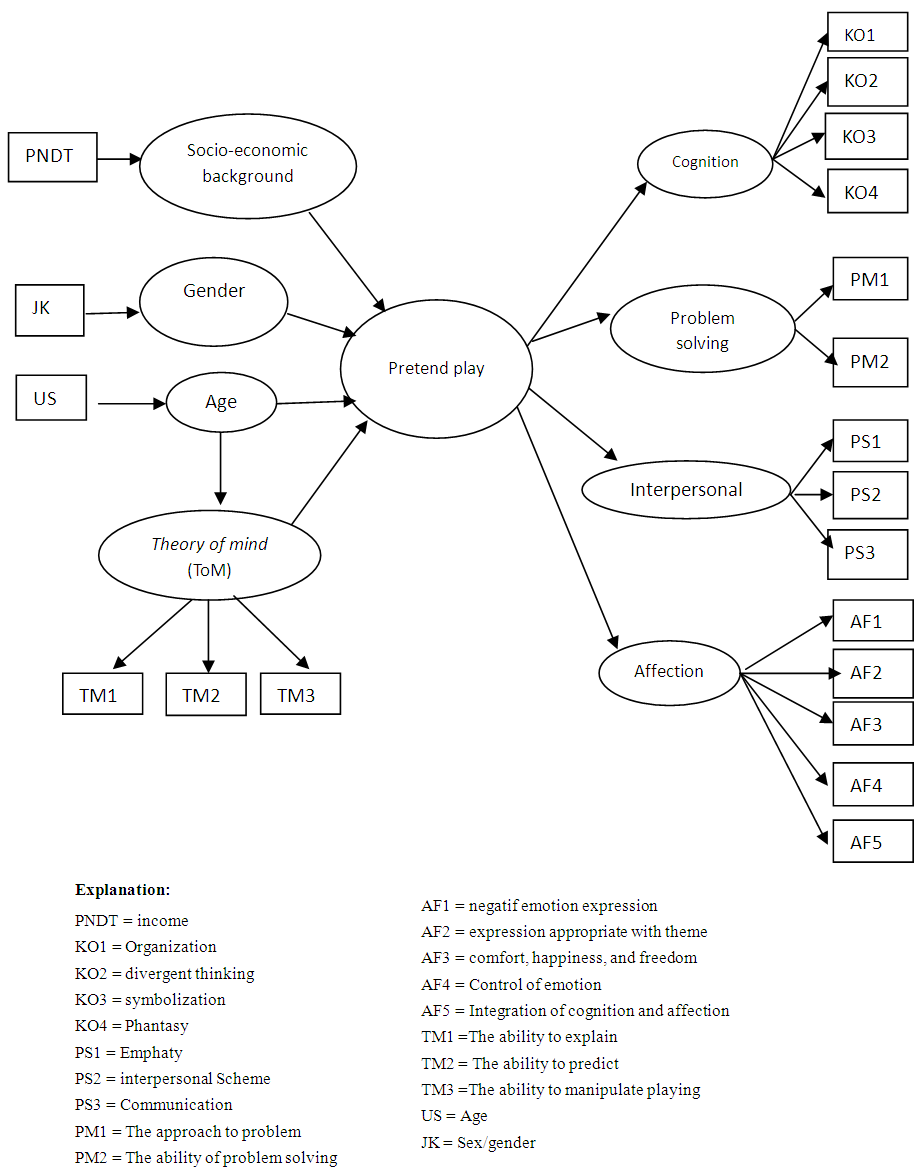

- The variables were called the latent variables or constructs known as the pretend play, age, gender, socio-economic background and theory of mind. There were 2 latent variables: endogenous latent variable i.e. pretend play; and exogenous latent variables or independent variables i.e. age, gender, socio-economic background and theory of mind. The latent variable of pretend play was second order which means that the variable was carried out two steps of measurements. At first, the variables were measured by four dimensions reflectively and each dimension was measured by some indicators that are reflective as well. Reflective relation showed the arrow’s direction derived from the latent variables to the four dimensions and from four dimensions to the indicator (Ghozali, 2008 and Yamin & Kurniawan, 2009, 2011). The latent variable of theory of mind was measured directly by three indicators that are reflective as well.Subjects in this study were a normal child which means they didn’t have problem physically and psychologically to involve with pretend play. Total subjects were 51 children, consisting of 22 boys and 29 girls. The age of subjects was between 36-84 months. The average age was 64.65 months. Subjects were living with parents having various socio-economic backgrounds. The data collection method was conducted by running record observation. Running records were conducted by CCTV. It was recorded the children playing approximately 1 hour. The video footage from CCTV was taken from four different angles. It was saved in the image storage program which still maintained four angles display. These would be used as rater assessments. The video footage was split per five minutes duration to make the work of rater more precise. Thus the raters could repeat per five minutes in order to sharpen the observation process.The observation instruments of the pretend play contain several indicators i.e. cognition, affection, interpersonal and problem solving (Russ, 2004). Guidance observation was 26 items consisting of 9 items of cognition, 7 items of affection, 6 items of interpersonal and 4 items of problem-solving. Each item in the form of observation was judged based on the phase developed by McCune-Nicolich. The scale’s value was from 0 until 4. It indicated how much the child performs the pretend play. Theory of mind instrument contained the children's ability to explain what is being played, predict what to do in the play and also to use the play instrument to do anything else. There were 9 items of theory of mind to guide observations. The age, gender and socio-economic background of children were performed by using the identity data and the documents at school. This study also measured content validity. Pretend play had content validity index 0.351 and theory of mind had content validity index 0.323. It could be interpreted that both instruments were quite valid.The research procedure was conducted through several phases. First phase was to study the theory as a basis for theoretical modelling. The second phase was assessments of several instruments i.e. the play instruments which is used in the pretend play, the measurement instrument of pretend play, and the measurement instrument of theory of mind by professional judgment associated with the play. Professional judgment in this assessment is kindergarten teachers and preschool teachers. The third stage was taking pictures of the children performing the process of pretend play in the playroom. The observation used one-way screen in the laboratory of Faculty of Psychology, University of Airlangga. Before the third phase was conducted, it was spread the consent form of child's participation to the parents. This is important for ethical research consideration (Cozby, Worden & Kee, 1989; Daniels, Beaumont & Doolin, 2002). The fourth stage was rater assessments of the children's playing process and ToM. Previously it was calculated inter-rater reliability of 4 raters. The result of inter-rater reliability showed rxx' = 0.913. It indicated that the inter-rater consistency is high, so it can be said that the each rater assessment was consistent with one another.Data analysis used Partial Least Square analysis (PLS). It was used software Smart PLS. Smart PLS gives measurement model or outer model and structural model or inner model (Ghozali, 2006; Jogiyanto & Abdillah, 2009; Yamin & Kurniawan, 2009, 2011). Evaluation Model of PLS consist of three stages i.e. evaluation of measurement model, evaluation of structural model, and the evaluation of the overall model (Ghozali, 2008, Yamin & Kurniawan, 2011).

| Figure 1. Theoretical model pretend play and theory of mind |

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Measurement Model

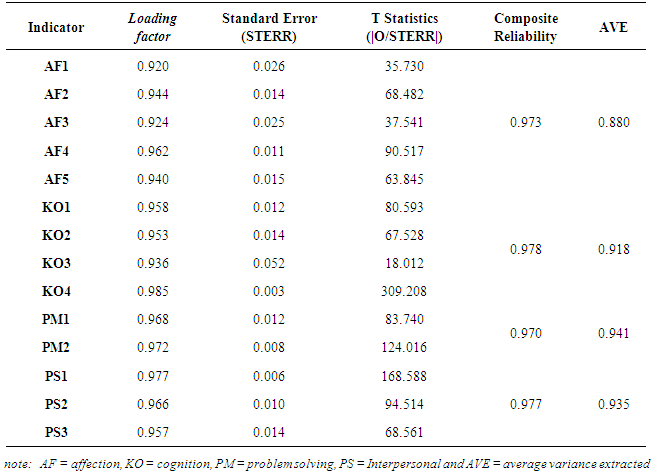

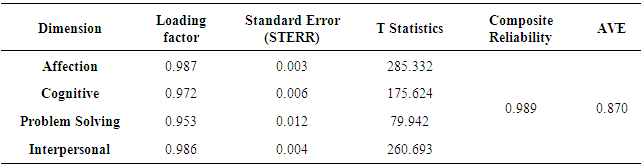

- The measurement constructs of pretend play was second order. At first order, construct of pretend play by the four reflective dimension i.e. cognition, affection, interpersonal and problem solving. Then, each of the dimensions was calculated its relationship with the indicators which was reflective as well. Theory of mind (ToM) construct was measured directly (first order) by three indicators that were reflective i.e explaining (TM1), predicting (TM2), and manipulating (TM3). PLS assessment criteria in the evaluation of the measurement model were performed through several stages: (1). Factor loading values should be above 0.70., (2). Composite reliability measuring internal consistency values should be above 0.60, and (3). Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values should be above 0.50. Discriminant validity was measured by two measurements i.e. cross-loadings and comparing the square root value of the AVE with the correlations value among latent variables. The square root value of AVE should be greater than the correlation value and between latent variables.

|

|

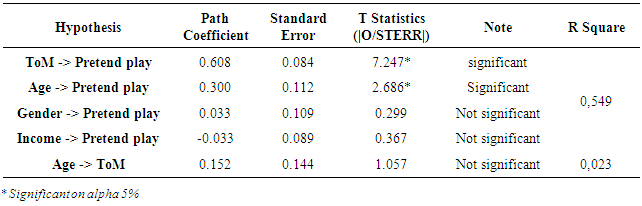

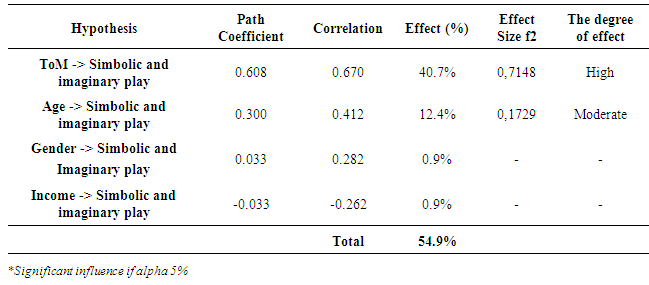

3.2. Evaluation of Structural Model

- Table 3 showed that theory of mind affected the pretend play. Age influenced the pretend play. Socioeconomic backgrounds represented from the parent income of children did not significantly affect on the children’s ability to pretend play. The hypothesis test results showed that age had no significant effect on theory of mind.

|

|

3.3. Evaluation of the Overall Model

- The result of GoF showed that GoF index was equal to 0.630. This value was more than 0.36. Thus it could be said that the theoretical models constructed had appropriateness with empirical model.

4. Discussion

- The constructed model had empirical compatibility. Thus the pretend play has cognition, affection, interpersonal, and problem solving dimensions affected by age, sex, parent’s socioeconomic status, and theory of mind. In a play, children have ability to imitate adults’ activity, not only practically but also they learn to understand how adults think, act, feel, and comprehend their world around them. The ability to understand other is a developed form of theory of mind. Theory of mind is a term to describe the comprehension of mind, believe, desire, and interest of others that different from themselves (Clifford & Stein, 2006). When children play a symbolic game, they can get out from the reality and use meta-perspective or in the attachment theory is called as reflective self functioning (Music, 2011). This is in line with Kavanaugh (2006) who said there are three conceptual approaches between pretend play with theory of mind i.e. modularity, simulation, and social cognition. Those conceptual approaches give review, if someone has theory of mind, he will master the meta-representation. Mental representation is a developed form of theory of mind and theory of mind influence the pretend play (Astington, 1998; Cassidy, 1998; Doherty, 2009; Keskin, 2008; Lillard, 2001; Mccathren, Yoder & Warren, 1999; and Mitchell & Riggs, 2000). Theory of mind has the capacity to explain the mental states to interpret others’ behaviour and manage the social interaction. Costall & Leuder (2004) and Nielsen & Dissayanake (2004) said that theory of mind is an unobserved aspect that can be seen by children play behaviour observation. Children’s theory of mind shows the ability to explain and predict human behaviour by considering human mind and feeling (Astington & Barrlault, 2001 and Doherty, 2009). Based on the second order analysis, the pretend play showed that cognition, affection, and interpersonal aspects gave high contribution to social and cognitive development aspects. A child performing the symbolic and imagination play in a sensitive period (preschool age) will have strong cognition, affection, and interpersonal ability (second order analysis result). It proves that preschool age is the right time to give the symbolic and imagination play as stimulus. If the children get the stimulus of the pretend play, then they can develop their cognition ability, able to understand others, and have interpersonal ability skill. This behaviour will develop children’s empathy, able to put themselves in situations, and have ability to communicate well. In the end children will grow into pleasant character.It showed that age significantly affected the pretend play; even though age only gave moderate effect but it indicated that the older children were better in playing the pretend play. The analysis showed that gender did not give significant effect to the pretend play, thus neither the boys nor the girls did not influence the score of the pretend play. Further analysis showed that the difference effect on gender was more based on the play selection. In addition, significant effect is also occurred on parent’s nursing. Parent assistance while the children are playing will give more significant effect on the children’s meaning for play selection (Lidz, 2003). The research result showed that norms shifting and the changing of parenting role affected the pretend play. The doctrine of specific play referring to gender is no longer applicable. Piaget, Vygotsky, and Parten (in Scarlett, 2005) said that the pattern of the pretend play among different gender has the same chance to move from non-symbolic play into symbolic play and from parallel play to cooperative play.Parent’s income had no significant effect on the pretend play. Although it is often presumed that the pretend play needs equipment supporting the symbolic and imagination process, but the analysis result showed that experience would support the children’s ability to symbolise and imagine, and it was not depend on the availability of the equipment at home. Age had no significant correlation with theory of mind, which means older children didn’t always show theory of mind improvement. Children needs stimulus to develop their theory of mind. Children are able to understand mental states since baby, but its development depend on the involvement and communication from people around (Collonesi, 2008), and according to Male (2001), people don’t automatically have a mature theory of mind since they were born. The descriptions above try to indicate that several matters related to theory of mind is not easy to identified especially the time when theory of mind starts to develop and how does theory of mind develop in line with age. However the research of O’Hare, Bremner, Nash, Happe & Pettigrew (2009) showed that the younger children have lower performance of theory of mind, but it doesn’t affirm that age affect theory of mind. Some of research journals related to the pretend play in children with special needs showed that they are having difficulty to play the pretend play. It happens due to the children with special needs’ is weak to perform perspective taking or difficult to perform symbolisation. It is due to cognition weakness or reluctant to have an interaction. Thus the pretend play which is stimulating and developing several dialogs will be hard to perform by children with special needs. Mendez and Fogle (2002) showed that the pretend play can be used to detect behaviour problem in children. MacDonald, Clark, Garrigan & Vangala (2005) said that the children with autism often fail to perform the pretend play, thus it needs to use video to teach the children several themes of the pretend play. Jarrold (2003) wrote that children with autism often have a problem of imagination, so that they are hard to pretend during the pretend play. Sheratt (2002) showed that children with autism need 4 months of intervention to understand the content of the pretend play without seeing the model. Barton (2007) showed that pretence behaviour in the pretend play can be taught to the children with special needs with some specific steps through imitating models e.g. imitating people drinking water or chewing food. At this point, the pretend play can be used to detect the weaknesses of the development aspects. In the other hand, the pretend play can be used as intervention or therapy for children with special needs, even though it needs structured implementation plan. This behaviour approach using the pretend play can help children with autism (Stahmer, Ingersoll & Carter, 2003). The pretend play is a tool to detect inabilities of cognition, affection, interpersonal, and problem solving. Sigafoos’ (1999) showed that some play behaviours are related to the children disabilities and it needs specific assessment based on children play behaviour to detect children disabilities. Stahmer, Ingersoll & Carter (2003) also analysed that the pretend play can be used to analyse the children behaviour and develop social skill of the children with autism spectrum. The pretend play can be used to detect cognition, affection, interpersonal, and problem solving matters in children, since its quality of cooperative play. That quality also makes the play able to detect and increase pro-social behaviours of the children. Deunk, Berenst & De Glopper (2008) said that the pretend play gives the children opportunity to change from one act to another. It makes the pretend play able to detect four aspects i.e. cognition, affection, interpersonal, and problem solving matters (Russ, 2004).

5. Conclusions

- There are several conclusions that can be drawn from this study: At first, the theoretical models constructed had goodness of fit model. The model of the theory constructed from variables or constructs of theory of mind, gender, age, socioeconomic background (income), and pretend play had a high goodness of fit model. Second, this study found that the age and theory of mind had significant influence on the pretend play. The degree of theory of mind influence to the pretend play was on the high category. It can be concluded that to perform pretend play, the children need to develop their theory of mind. Thus, the more children are able to perform the pretend play, the more develop their theory of mind. Third, the ability of the children to perform the pretend play was not influenced by gender and socioeconomic background of parents. Fourth, the measurement instruments of the pretend play can be used as tools to detect child cognition, affection, interpersonal and problem solving since early childhood, or it may also become the tools of "healthy play", because it stimulates aspects of cognition, affection, interpersonal and problem solving of the child.According to the study, there are several recommendations as follows (1) As a guide to observe aspects of cognition, affection, interpersonal and problem solving in preschool children, the observation guidance of the pretend play can be used as a means to detect the weaknesses of those aspects to the child since early childhood, and it also can be used as a tool in to stimulate those four aspects. Thus, the pretend play can be used as a part of play therapy accompanied by structured program of therapy (2) The development of theory of mind is the children's ability to recognize mental states of their selves and others. The application of theory of mind may include the development of children’s empathy, thus to develop theory of mind can be conducted through pretend play, but it needs to be performed in the sensitive period at the age 3 to 7 years. (3) The result also showed that theory of mind had high influence on pretend play. Thus, to perform the pretend play, the child needs to develop his theory of mind. In order to do pretence, the stimulation of pretend play would indicate an early development of theory of mind. According to that statement, when the children are at sensitive age of the development of theory of mind, the children need to be avoided as much as possible with the individual games such as game based on technology. (4) The preschool children are not only expected to know the physical reality of other people but they also need to know the concepts, knowledge, desires, thoughts, memories and intentions of others. If the children are only taught the ability to recognize the physicality of others, but they are not taught to understand what other people think, will, and wish, then in the future it will be hard to find people who have empathy to others. It is known that the function of theory of mind in everyday life is persuasion, empathy and self-awareness.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML