-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2016; 6(3): 56-63

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20160603.02

Influence of Demographic Variable on Quality of Life among Women in Ibadan Metropolis, Oyo State of Nigeria

Okhakhume Aide Sylvester , Aroniyiaso Oladipupo Tosin

Psychology Department, University of Ibadan, Ibadan Nigeria

Correspondence to: Aroniyiaso Oladipupo Tosin , Psychology Department, University of Ibadan, Ibadan Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

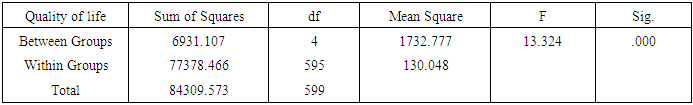

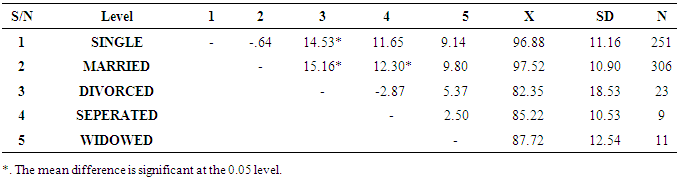

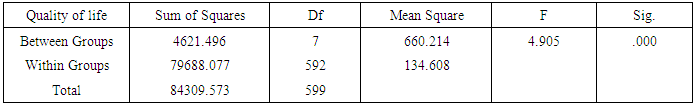

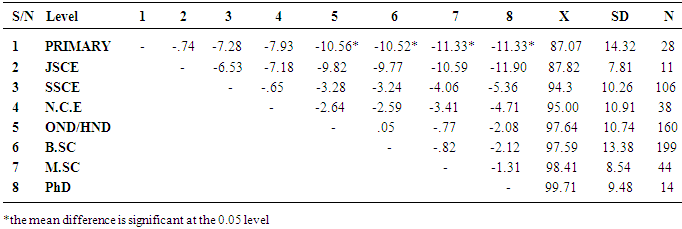

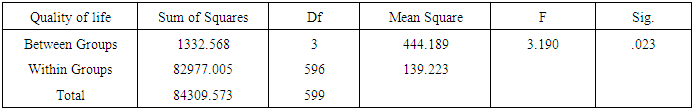

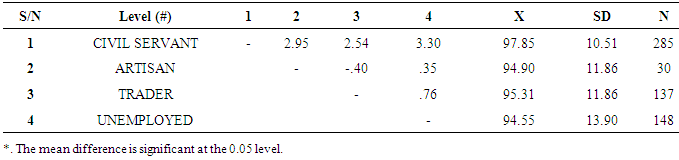

The issues of poor quality of life among Nigeria women results to inadequate participation of women in the development of the country, high rate of maternal death, increasing rate of mentally, physically challenge and high rate of financial handicap of Nigeria women, which have significant influence on the society at large attracted attention of this study. This study examined influence of demographic variable on quality of life among women in Ibadan metropolis, Nigeria. The study utilized cross-sectional research design which involves the use of self-report questionnaire for data collection. A total number of 600 women participated in the study. Results outcomes shows that marital status had significant influence on quality of life at (F (4/595) = 13.324, P<0.05). The result also revealed that religion income and occupation had significant influence on quality of life of women in Ibadan metropolis (F (2/597) = 7.267, P<0.05. F (7/592) = 4.905, P<0.05 & F (3/596) = 3.190, P<0.05). It was concluded that marital status, religion, educational attainment, income and occupation of women living in Ibadan metropolis significantly influence their quality of life. Therefore, this study recommends that women should seek to acquire more knowledge through their educational status and government should create conducive workplace climate and improve financial assistance programme to built economic status of Nigeria women.

Keywords: Quality of Life, Religion, Marital Status, Occupation, Educational Attainment, Income

Cite this paper: Okhakhume Aide Sylvester , Aroniyiaso Oladipupo Tosin , Influence of Demographic Variable on Quality of Life among Women in Ibadan Metropolis, Oyo State of Nigeria, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 6 No. 3, 2016, pp. 56-63. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20160603.02.

1. Introduction

- Adversely, poor quality of life is identified to be early warning signs of maternal death, health disorders and poverty. Quality of life (QoL) of women is each individual’s perception of her position in life, in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns (WHO, 1997). It is a broad ranging concept, affected in a complex way by the women’s physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs, and relationship to salient features of the environment (WHO, 1997). Medical and psychological interest in Nigerian women quality of life has been stimulated by the report of Women Health and Action Research Centre, an organization committed to the promotion of intimate and reproductive health and social well-being of women and adolescents that out of 100,000 women that enter labour rooms, 50 of them do not come out alive (death of 50 women per 10,000), which was as a result of poor quality of life of women. (Ariel, 2013). Also, the success in prolonging life and the realisation that women under treatment want to live and not merely survive (McDowell & Newell, 1996). It appears that the concept of quality of life among women is fast becoming a popular concept worldwide including Nigeria, may be because of its impact on the society at large as a result of inappropriate functioning of women in the society or may be most women in Nigeria had a misconception of reasonably clear idea of what sorts of things would enhance their individual quality of life (and probably the quality of life of other individuals too). However, studies had shown that many factors influence quality of life, i.e. physical, spiritual and health state, independence level, social relationship with the environment and others (Ruzevicius, 2006; Shin, 1979; Bagdoniene, 2000), dwelling, employment, income and material well-being, moral attitudes, personal and family life, social support, stress and crisis, condition of health, prospects of health care, relationship with the environment, ecologic factors, etc. (Juozulynas and Čemerych, 2005; Rugiene, 2005; Phillips, 2006). Quality of life in the urban setting according to Phillips (2006) is a multifaceted phenomenon determined by the cumulative and interactive impacts of numerous and varied factors like housing conditions, infrastructure, and access to various amenities, income, standard of living and satisfaction about the physical and social environment. According to this author, the two indicators of quality of life which are subjective and objective are pointing to two different things. Subjective indicator focuses on pleasure as the basic building block of human happiness and satisfaction of quality of life while objective indicator on the other hand, focuses on a radically different perspective. To those who are working with this indicator, the important question to ask at the individual level are whether people are healthy, well fed, appropriately housed, economically secured and well educated or not rather than whether they feel happy.However, quality of life (QoL) has been recognized as an important construct in a number of social and medical sciences such as sociology, political science, economics, psychology, philosophy, marketing, environmental sciences, medicine, and others. However, each academic field has developed somewhat different approaches to investigate the construct of quality of life. For example, sociologists and political scientists are often interested in the quality of life at the societal or population level ("state of the state"), while psychologists and medical scientist are interested in measurable aspects of individual under subjective experiences of a good life ("state of the person") (Rapley 2003). In each case, the construct is conceived and measured differently. Erikson (1993), posited that quality of life in terms of control over resources. Lane (1996), highlight high quality of life in terms of subjective well-being, human development, and justice.Moore so, within the field of healthcare the term quality of life (QOL) refer to the general well-being of individuals and societies. The term is used in a wide range of contexts, including fields of international development, healthcare, and politics. Quality of life should not be confused with the concept of standard of living, which is based primarily on income. Instead, standard indicators of the quality of Life include not only wealth and employment, but also the built environment, physical and mental health, education, recreation and leisure time, and social belonging. Also is often regarded in terms of how it is negatively affected, on an individual level, a debilitating weakness that is not life-threatening, life-threatening illness that is not terminal, terminal illness, the predictable, natural decline in the health of an elder, an unforeseen mental/physical decline of a loved one, chronic, end-stage disease processes. Quality of Life (QOL) has long been an explicit or implicit policy goal; adequate definition and measurement have been elusive. Diverse "objective" and "subjective" indicators across a range of disciplines and scales, and recent work on subjective well-being (SWB) surveys and the psychology of happiness have spurred renewed interest and frequently related concepts such as freedom, human rights and happiness.Demographic variable has been linked to quality of life. However, research to date has not clearly delineated the direction and strength of the link some demographic variable to quality of life such as ethnicity. Anglo female adolescents reported higher quality of life scores than African American female adolescents in a study conducted by Dew and Huebner (1994). Inversely, the same study revealed that African American male adolescents were found to have higher quality of life scores compared to Anglo male adolescents. Near, Rice, and Hunt (1978) found that non-Anglo adult males indicated less satisfaction with their lives and jobs than did adult Anglo males. Similarly, Mookherjee (1992) concluded that Anglos indicated a higher quality of life compared to African Americans. Most of this data indicates that family income is positively related to quality of life (Campbell, Converse, & Rodgers. 1976; Mookherjee, 1992). Edwards and Klemmack (1973) determined that there is a positive relationship between income and overall life satisfaction. Families with a higher income revealed that they had a higher quality of life than lower income families (Metzen, Bradley, & Helmick, 1986). Research conducted by Palmore and Luikart (1972) indicated that income was more strongly linked with quality of life in participants with lower incomes.Furthermore, older middle aged participants indicated that income was less related to quality of life than younger middle aged participants (Palmore & Luikart, 1972). Higher education levels had also been positively linked to perceptions of well-being (Mookherjee, 1992; Campbell, 1976; Edwards & Klemmack, 1973). Family composition, including number of siblings and number of parents in the home, has become a part of many studies seeking to determine it influence on quality of life. The classic literature on quality of life during the 1970s and 1980s reported that overall quality of life was predicted by evaluations of satisfaction with different domains of life, such as health, work, friends, community, standard of living and relationships with family. It was therefore accepted that life satisfaction is a social indicator of quality of life (e.g. Andrews and Withey 1976, Campbell et al. 1976). Sirgy (1998) has labeled this as a hierarchical or spill over model. He argued that spill over can be either vertical (in either direction so that people who are satisfied with their standard of living are likely to be satisfied with their lives overall or overall satisfaction may make a person more predisposed to evaluate their standard of living more favorably) or horizontal (the domains which influence overall satisfaction can affect each other (e.g. satisfaction with material areas of life might influence satisfaction with relationships with family). Some of the rural dwellers are not satisfied with their lifestyle, thereby creating a problem in their family and striving at all cost to migrate to the urban areas to get a good life. Nadel (2004) conducted a year follow up study on how personality predicts quality of life in pediatric patients with unintentional Injuries. Participants include One hundred and seven pediatric injury victims (6-14 years old) which completed an interview on health-related quality of life and were rated on the personality domains of the five-factor model by their mothers a month and a year after the Incident. Result showed that health-related quality of life was compromised after one month, particularly in the physical domain, but improved significantly after a year. Lower health related-quality of life after a month was predicted by injury severity, functional status, and neuroticism. After one year, lower health-related quality of life was predicted by concurrent functional status and neuroticism. The main finding of this study was that health-related quality of life in injured children is affected by personality, after controlling for age, gender, and most importantly injury severity and functional status.Purpose of the study This study is set out to achieve a main objective, which is to investigate the influence of demographic variable (marital status, religion, educational attainment, income and occupation) on quality of life among women in Ibadan metropolis, Oyo state, Nigeria. Hypotheses1. There will be a significant influence of religion on quality of life among women in Ibadan North and Akinyele Local Government Area of Oyo state, Nigeria.2. Income will significantly influence the quality of life among women in Ibadan North and Akinyele Local Government Area of Oyo state, Nigeria.3. There will be a significant influence of marital status on quality of life among women in Ibadan North and Akinyele Local Government Area of Oyo state. Nigeria4. Educational background will significantly influence the quality of life among women in Ibadan North and Akinyele Local Government Area of Oyo state, Nigeria.5. There will be a significant influence of occupation on quality of life among women in Ibadan North and Akinyele Local Government Area of Oyo stale, Nigeria.

2. Methodology

- Research DesignThe study design method was cross sectional research design. The independence variables of the study include demographic variable (religion, marital status, education background and income), While dependent variable was quality of life.Research Setting The study was carried out in Ibadan metropolis. Ibadan is the largest traditional, urban centre in Southwest Sahara in Africa with an estimated population of appropriately five million (National Population Commission, 2006 provisional census report). Ibadan, an old city state, constituted many tribes, but is mainly dominated by Yoruba speaking people. It is one of most absorbers of migrants in Nigeria because of its centrality. The metropolis comprises of five local government areas (LGAs). Historically, Ibadan emerged around the second quarter of the 19th century as a war town later developed into a commercial centre. Economically, Ibadan is dominated by middle men and women engaged in trading and commercial activities. Such as road side mechanics, artisans (plumbers, bricklayers, radionics, painters etc) domestic servants, gardeners, night-watch men, guards, and hawkers. Ibadan is equally well equipped with institutions at the pre-nursery, nursery; primary, post primary; polytechnics, teaching hospital and University. This service sector essentially cushions the unemployment of the growing urban population.Study Population The general population of interest in this study was women in Ibadan metropolis. Women, who are between the age range of 25 and 80 years were the focus of the researcher. This was the main reason why quality of life scale (1996) was used. It has theoretical relevance for the study. The participants were drawn from communities that consisted Ibadan metropolis. The sample consist of women who are from various socio economic class, which include academician, and other allied professions. The socio- economic diversity of the sample adds to the generalization to the study. A total of 600 participants took part in the study. The aggregate sample had the following demographic characteristics, the respondent consist of 600 (100%) females. The average age was 40.5 years. Educational attainment distribution, 199 (33.2%) were B.Sc holder, 160 (26.7%) were OND/HND holder, 106 (17.7%) were SSCE holder, 44 (7.3%) were M.Sc holder, 38 (6.3%) were NCE holder, 28 (4.7%) were primary certificate holder, 14 (2.3%) were PhD Holder and 11 (1.8%) were JSCE holder. Majority of the participants were B.Sc holder. Their marital status varies from single to widowed, 251 (41.8%) were single, while 306 (51.0%) were married, 23 (3.8%) were divorced, 9 (1.5%) were separated and 11 (1.8%) were widowed. On religion characteristics 465 (77.5 %) were Christian, 125 (20.5%) were Muslims, and 10 (1.7%) were from other traditional officiated religion groups. Sampling TechniqueThe sampling techniques used in selecting the samples for the study were non-probability sampling technique. In this technique, normal distribution of the population is not assumed unlike the probabilistic sampling. In this present study, for the purpose of clarity, purposive or judgmental sampling which is one form of non-probabilistic techniques was used. It involves the use of participants that were available during the time or period of research investigation. Purposive sampling is widely accepted and used mainly in exploratory or field research survey (Babbie, 1998, 195). InstrumentsQuestionnaires were used to collect relevant information from the participants of the study. The questionnaire was divided into two segments with each of the segments tapping information based on the identified variables of interest. It comprised of two sections; A and B. The structure of the questionnaire is outlined below.Section A: Demographic characteristics In this section of the questionnaire, demographic information of the participants were captured ranging from age to their highest level of income. This section consisted of variables such as age, marital status, religion, occupation, educational background and income.Section B: Quality of Life scale (WHO 1996) WHO Quality of Life Bref Scale (WHO QOL-Bref) was developed by the World Health Organisation (1996). The scale was developed by a committee drawn from all over the world and has been validated in many countries, it has some claim to being culture free. Sokoya of the University of Ibadan Teaching Hospital has used the instrument. She also produced a Yoruba version by the back translate method. The WHO QOL-Bref has 26-items, each of which carries 5-part Likert type response alternatives. It is scored over four major domains; physical, psychological, social relationships and environment. The instruments place primary importance on the perception of the individual. By focusing on individual's own views of their wellbeing, the instrument inquires not only about the functioning of people with certain diseases disorder but how satisfied the patients are with their functioning and with effects of treatment (Medical Outcome Trust, 1997). However, the responses alternatives ranges from 'Not at all', with a pre-assign value of "1" to and extreme amount' with a pre-assign value of "5". The responses are scored from the most negative item to the most positive item. Thus, the higher the quality of life experienced by the respondent, the better he/ she is satisfied with life. With the pilot test sample, the resultant 25 - item scale yielded alpha coefficient of .70 and a split half reliability of .80 and Guttman split-half reliability coefficient yielded .82.Procedure for Data Collection Permission was first sought from Oyo state ministry of social affair, community development and women welfare. Also, from women leaders of various communities that constitutes the study area before the administration of the questionnaires. The researcher then administered six hundred and fifty questionnaires with the help of research assistance (chairperson among market, women leader), six hundred and twenty were retrieved and six hundred questionnaires were accurately satisfied. Prior to the given questionnaire to fill, the inform consent form attached to the questionnaire was first given to the respondent to fill and sign and the researcher instructed them on how they were expected to respond to the statement in the questionnaire and also informed them that their confidentiality was guaranteed and therefore they should not write their names on the questionnaire.

3. Results

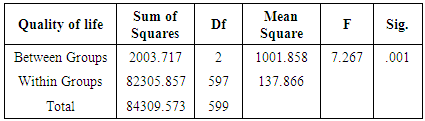

- Research Hypothesis one which stated that there will be a significant influence of religion on quality of life among women in Ibadan Metropolis was tested using One-Way ANOVA and the result is presented on table 1;

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

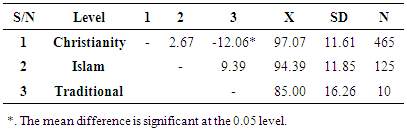

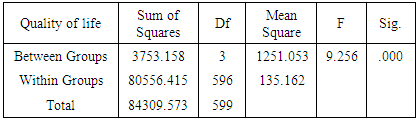

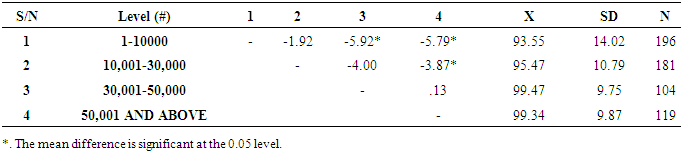

- Findings in the area of quality of life had laid much emphases on the objective measures of quality of life especially in the medical community and less on the subjective measures of quality of life. It also appears that there is lack of emphasis on the manner in which quality of life of urban life is related to the circumstances of urban dweller's demographic characteristic. Due to this shortcoming, there is need to emphasis and relate the notion of quality of life to objective and subjective well- being of urban people and also to explain the role of demographic variables on quality of life.Hypothesis one predicted that religion had a significant influence on quality of life of women living in Ibadan metropolis. The hypothesis was confirmed, meaning that religion had significant influence on quality of life with the Christian women reported higher quality of life than other women from other religion group. This was consistent with the finding of Dongen 1996, that demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, religion, habitual status, level of education, having children and finances) have a relationship with outcome scores of quality of life or relating concepts, such as life satisfaction and well-being. Also, Mirella et al 2005 found that socio-demographic variables such as being female, unmarried, lower educational level, religion and older age are the major vulnerability factors predicted a worsening of objective quality of life over time.Hypothesis two revealed that income had a significant influence on quality of life of women living in Ibadan metropolis. The hypothesis was confirmed, meaning that the findings of the study showed that income had significant influence on quality of life. Also the result revealed multiple comparisons significant difference between the levels of income in the posthoc analysis meanwhile in the descriptive analysis, the result revealed that women with high income had high quality of life unlike other women with lower income. This was supported by Lang et al. (2002) that marital status, employment, superior economic status, age, few medication side effects, and low psychopathology were positively had influence on quality of life. Richmond et al. (2000) also confirmed that demographic characteristics, such as income, presence or number of children in the home and township, gender, age, marital status, and education had significant influence on quality of life of women.Also, Hypothesis three predicted that marital status will significantly influence quality of life of women living in Ibadan metropolis. The hypothesis was confirmed, meaning that the findings of the study showed that marital status had significant influence on quality of life with married women reported higher quality of life. Also the result revealed multiple comparisons significant difference between marital status in the posthoc analysis meanwhile in the descriptive analysis, the result revealed that women that are single had high quality of life unlike other women that were married, separated, widowed among women in Ibadan metropolis. This was supported by Mirella et al 2005, that socio-demographic variables such as being female, unmarried, lower educational level and older age are the major vulnerability factors predicted a worsening quality of life over time. Also supported by Marks and Fleming (1999) and Kim and McKcnry (2002) that being married had a positive influence on well-being. Barry (1997) concluded that there are modest relationships between demographic characteristics (e.g., finances, leisure, family, living situation and social relationships) and quality of life.Furthermore, Hypothesis four predicted that educational attainment will have significant influence on quality of life of women in living in Ibadan metropolis. The result confirmed the stated hypothesis and most studies that examine relationship between educational attainments and quality of life also found that there is a significant relationship between education and quality of life which support the result of this study. Individuals with higher levels of education reported better quality of life, as an index of socio-econornic position, higher levels of education provide entree to higher status occupations with greater pay. The near-ubiquity of education effects point toward a previously identified socioeconomic gradient (Breeze et al., 2004, Kempenet ah, 1997).Finally, Hypothesis five predicted that occupation will significantly influence quality of life of women living in Ibadan metropolis. The hypothesis was confirmed. Also the result revealed multiple comparisons significant difference between the occupations in the posthoc analysis meanwhile in the descriptive analysis, the result revealed that women that were civil servant had high quality of life unlike other women that were artisan, trader and unemployed among women in Ibadan metropolis. Individuals with secured and good pay job reported better quality of life, higher status occupations with greater pay as an index of socioeconornic position which significantly influence quality of life (Breeze et al., 2004, Kempenet ah, 1997). Also consistent with the study by Pichler (2006) who reported that employed women, young adults and careers positively correlate with quality of life.

5. Recommendations & limitations

- The purpose of this study was to examine the influence of demographic variables on quality of life of women in Ibadan metropolis. It has been discovered that some demographic factors of the women goes a long way in determining their quality of life.Hence, government and non-governmental organizations can help in boosting the quality of life of women in Ibadan metropolis by;1) Providing an enabling environment for the women in Ibadan metropolis to use their skills and knowledge to generate reasonable income for themselves and to improve their living standard.2) Making basic services (education, health, food and nutrition, maternal and child care, housing, transportation etc.) available and affordable to the less privileged women in Ibadan metropolis.3) When asked, they said they wanted good roads, potable water supply, gutters that can take the passage of water in raining seasons, a bridge to climb due to the waterlogged areas. They also asked for stable electricity, affordable and better health care and facilities. To them, this can also improve their quality of life.The research is limited to the demographic variable and quality of life, other factors such as; environmental factors, personality factors and disabilities among Nigeria women should also be considered for further research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML