-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2016; 6(2): 41-46

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20160602.04

The Fear of Missing out Scale: Validation of the Arabic Version and Correlation with Social Media Addiction

Jamal Al-Menayes

Department of Mass Communication, College of Arts, Kuwait University, Safat, Kuwait

Correspondence to: Jamal Al-Menayes , Department of Mass Communication, College of Arts, Kuwait University, Safat, Kuwait.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study seeks to examine the psychometric properties of an Arabic version of the Fear of Missing out scale (FoMO). FoMO is defined as. A pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent, FoMO is characterized by the desire to stay continually connected with what others are doing. Factor analysis showed the Arabic FoMO scale to consist of two distinct factors. Reliability tests indicated that the two factors had good internal consistency. Concurrent validity analysis based on correlating FoMO with a scale measuring social media addiction yielded highly significant results supporting its suitability for use in further research. Future research should do further testing of the scale's reliability and validity in different parts of the Arabic-speaking world to uncover its strengths and weaknesses and the possible need for additional refinement.

Keywords: Social Media, Addiction, Fear of Missing Out, Psychometrics

Cite this paper: Jamal Al-Menayes , The Fear of Missing out Scale: Validation of the Arabic Version and Correlation with Social Media Addiction, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 41-46. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20160602.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Dependence on computer-mediated communication (CMC) is a phenomenon that has received considerable attention in the literature. Research has focused on the over-reliance on networked computers in our daily lives whether the setting is work-related or at home. The notion of Internet dependence was first discussed by Young as a form of addiction worthy of study. [1] The author went as far as constructing a scale to measure its occurrence and gauge its consequences. This scale has been used widely since its introduction in several languages and many iterations. The Internet Addiction Test (IAT) has been used in Chinese [2, 3], Italian [4], French [5], Arabic [6] and Turkish. [7] It has also been employed to study the effects of Internet addiction on a host of other variables such as Academic performance [8, 9], depression [10, 11] and introversion. [12]More recently the interest in CMC dependence has shifted toward the use of mobile phones as a device of choice used by many. Mobile phones are essentially small, networked computers. The clear advantage of mobile phones over traditional desk computers and laptops is their mobility and lower power consumption. This has led to excessive dependence on them for CMC in the form of text messages, chat rooms, picture sharing, in addition to voice communication. The decreasing operational costs of the mobile phone over the years has made it within the reach of a much wider segment of the population in many countries, especially among youth.Another development that led to the attractiveness of mobile phones is the introduction of mobile social media. These applications enabled users not only to communicate with one another, but to communicate with the entire world in text, sound and vision. Social media applications are quite flexible regarding how public the communication is. Users can have private groups where only invited and approved individuals can gain access. They can also customize their applications in terms of how public their content is.The mobility and versatility of mobile devices equipped with social media have led to what some researchers label Social Media Addiction. Some argue that this phenomenon is essentially an extension of Internet Addiction differing only in the means of delivery. Others postulate that it is a qualitatively different phenomenon warranting separate research. Korpinen, for example, argued that mobile devices usage is associated with levels of anxiety not seen before with traditional laptops or desktop computers. [13] In my own research, based on cross-sectional surveys of university students, I found a significant association between mobile phone usage and academic performance. It appears that the more students use their mobile phone, the lower their grades. [14] Przybyiski and his colleagues dropped the use of terminology such as "dependence" or "addiction" to describe the correlates of social media usage and opted to use the term "Fear of Missing Out" (FoMO). [15] FoMO is postulated to be a by-product of heavy social media usage. In the following section, I will discuss this concept of FoMO as it was first introduced both conceptually and empirically. Afterward, an attempt will be made to test the psychometric properties of a version of the scale based on the Arabic language. I will attempt to measure the scale's reliability by statistically testing its internal consistency. In addition, I will test the scale's concurrent validity by correlating it with a measure of social media addiction presumed to have a theoretical link to it.

2. Fear of Missing out (FoMO)

- The current study is based on Self-Determination Theory (SDT) which is a theory of motivation. It is concerned with supporting our natural or intrinsic tendencies to behave in effective and healthy ways. SDT represents a broad framework for the study of human motivation and personality. SDT articulates a meta-theory for framing motivational studies, a formal theory that defines intrinsic and varied extrinsic sources of motivation, and a description of the respective roles of intrinsic and types of extrinsic motivation in cognitive and social development and in individual differences. [16, 17]Rooted in the self-determination theory (SDT). Przybylski et al. suggest that FoMO could serve as a mediator linking deficits in psychological needs to social engagement. Fear of Missing Out is defined as: "a pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent, FoMO is characterized by the desire to stay continually connected with what others are doing." [18] In a sense, the concept of FoMO is not an addiction to the medium, but what the medium can do for the user. It is not about missing your mobile phone; it is about fear of not being part of what your friends are doing. The medium here gives the user taps on what his or her friends are doing. It does not matter as much that you are not part of it, but rather that you know about it in detail. The mobile device and its social media fulfill the need to know about what one's friends are up to at any given time. To reiterate, what the user missing here is face-to-face activity and not the mobile itself. The mobile device is simply an enabler to participate in direct interaction with others.Participation in social media may be particularly attractive to those who fear missing out. Applications such as Whatsapp, Twitter, and Instagram can prove to be technological enablers for those seeking social connection and provide the assurance of greater levels of social connectedness. [19] In several ways, social media applications can be seen as reducing the "cost of admission" for being socially engaged. This is especially true for those who struggle with fear of missing out. In this sense, social media present an efficient, low-cost path for those who feel the need to be continually connected with what is going on in their social circles while they are away. The implication here is the higher a person is in his or her fear of missing out, the more they will gravitate towards social media.It is worth noting that there is very little known about this phenomenon. In a recent study Alt found that FoMO is negatively related to those with high intrinsic motivation and the opposite is true for those with high extrinsic motivation. [20] In another study based on survey results and focus group data collected from study abroad students, Hetz et al. found that students studying abroad used social media primarily for purposeful communication among themselves, in addition to connecting back home. [21]

3. Research Questions

- With the dearth of studies examining FoMO, there is no empirical examination of the instruments used to measure the phenomenon itself. To the knowledge of this author no attempts have been made to assess the psychometric properties of the self-report scale used to measure the fear of missing out. The current study aims to address this issue by examining the reliability and validity of the FoMO scale in Arabic. More specifically, the study aims to answer the following research questions:(1) How many factors underlie the FoMO scale, and what are they?(2) What is the internal consistency of the FoMO scale?(3) To what extent is the FoMO scale concurrently valid?

4. Method

4.1. Participants

- A total of 1327 undergraduate students enrolled in communication courses in a large state university completed a self-administered survey questionnaire over a period of four months during the academic year in 2014. The sample was selected based on convenience and, therefore, it is not a probability sample. Students were assured of anonymity and confidentiality, and participation was voluntary. A research assistant distributed the questionnaires at the beginning of each class and the time it took to fill it out is just under ten minutes. The age of the respondents ranged from 18 to 31 with 96% ranging between 18 to 25 years of age. The mean age of the participants in the study was 21.87 years. The participants were 395 (29.8%) male and 931 (70.2%) female. This gender distribution reflects the enrollment profile of the university student body that is 70% female. The self-administered questionnaires were distributed during regularly scheduled class sessions.

4.2. Measurement

- Fear of Missing Out Scale (FoMO)The FoMO scale consisted of 10 items translated to Arabic from the English scale proposed by Przybyiski et al. [18] The items were rated on a five-point Likert scale as follows: strongly applies to me, applies to me, somewhat applies to me, applies to me very little, does not apply to me at all, scored 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1 respectively. The sample size is sufficient for a scale consisting of 10 items as will be shown later in the analysis.

4.3. Social Media Addiction Scale (SMAS)

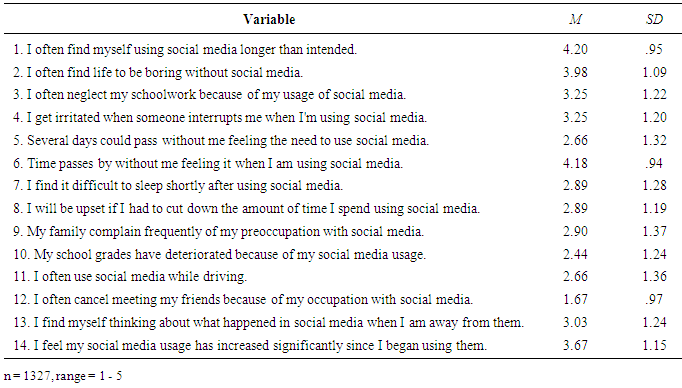

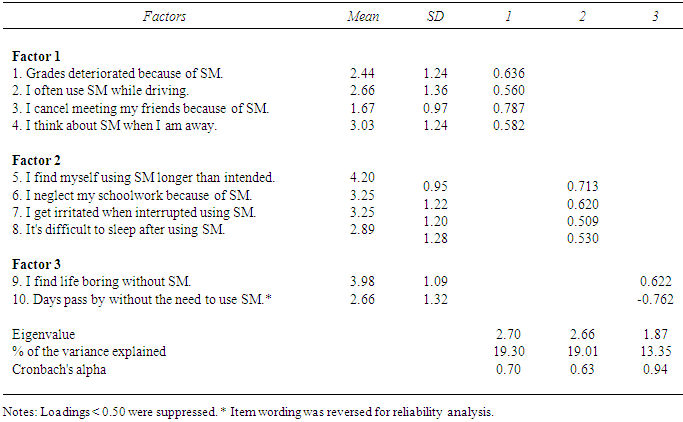

- The SMAS consisted of 14 items adapted from the IAT to fit the context of social media usage. The items were rated on a five-point Likert scale as follows: strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree, scored 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1 respectively. The items will be factor analyzed and used for establishing the concurrent validity of the FoMO scale.

5. Results

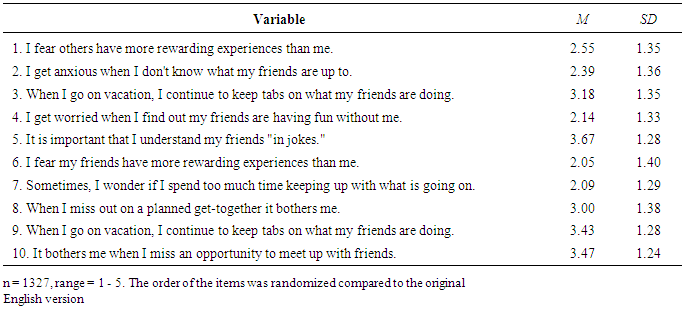

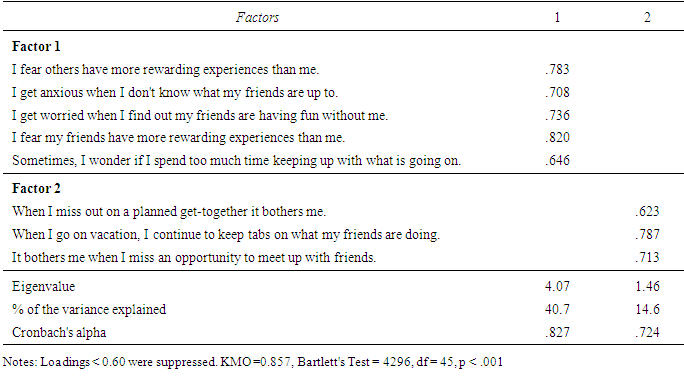

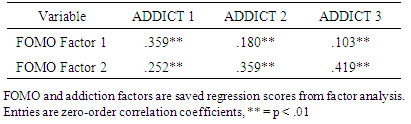

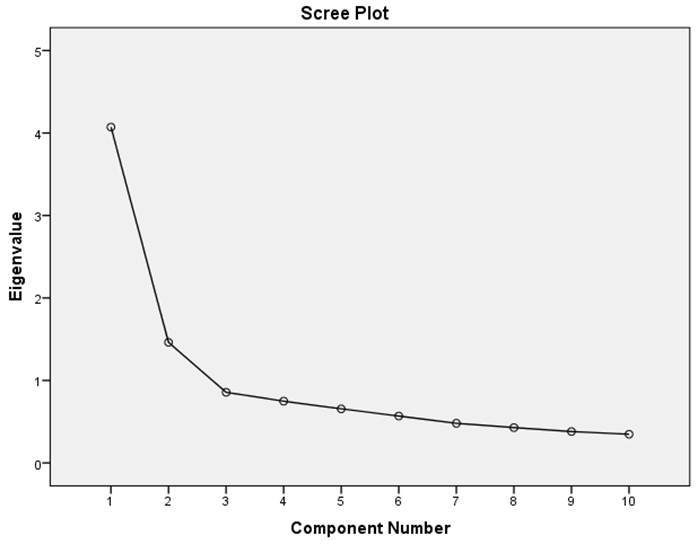

- The first research question asked about the dimensionality of the FoMO scale. To answer this question, the scale underwent factor analysis using principal component analysis with Varimax rotation. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of the FoMO scale along with the wording of each item. Table 2 shows results of the factor analysis of these items. As can be seen, the Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) is 0.857 indicating that the sample size is adequate for the number of items in the scale and factor analysis is appropriate for this data set. Bartlet's Test of Sphericity has a Chi Square of 4296 which is significant (p < .001) further supporting the suitability of the data for factor analysis.Factor analysis of the FoMO scale produced two significant factors. The first factor consisted of five items while the second factor contained three items with Eigenvalues of 4.07 and 1.46 and explained variance of 40.7 and 14.6 percent respectively (see Table 2). For a graphic representation of these results figure 1 shows a scree plot clearly indicating a two-factor solution for the FoMO scale. This is indicated by the fact that only two factors are above the 1.00 Eigenvalue line. The result is different from the original English version which yielded a single factor solution based on the same number of items items. [15]

|

|

| Figure 1. Scree Plot of Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) Factors |

|

|

|

6. Conclusions

- This study examined the psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the Fear of Missing Out scale (FoMO). FoMO is a feeling of uneasiness that others might be having gratifying experiences which someone is not a part of. Results showed that the Arabic FoMO scale is internally consistent. They also showed that the scale scored high on a test of concurrent validity involving another scale measuring something with theoretical affinity to FoMO namely social media addiction. These results pave the way to further studies of FoMO on Arabic speaking samples. This finding is significant because of the dearth of empirical work on these and similar phenomena related to social media in the Arab world. Future research utilizing the Arabic measurement of FoMo should do further testing of its reliability and validity in different parts of the Arabic-speaking world to reveal its strengths and weaknesses and the possible need for additional refinement.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This research was supported and funded by Kuwait University research grant no. (AM04/15)

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML