-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2016; 6(1): 20-26

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20160601.04

Cultural Influences on the Structure of Emotion: An Investigation of Emotional Situations Described by Individuals from Cambodia, Japan, UK and US

Mariko Kikutani1, Machiko Ikemoto1, James Russell2, Debi Roberson3

1Faculty of Psychology, Doshisha University, Japan

2Boston Collage, USA

3University of Essex, UK

Correspondence to: Mariko Kikutani, Faculty of Psychology, Doshisha University, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The present study investigated whether people from different cultures associate emotions with events differently, and if these differences are observable in the underlying structure of these emotions. Eighty-two participants from four different countries: Cambodia, Japan, the UK, and the US, were asked to describe situations in which they would feel one of the following ten emotional states: surprise, happiness, excitement, satisfaction, relaxation, sleepiness, sadness, cold anger, hot anger, or fear. A total of 2541 situations were described by the participants and categorized by researchers into 38 groups according to their content; for example achievement, separation, or anxiety. The frequency of content types reported in each emotion varied across the four countries, but a greater consensus was observed for positive emotions than for negative ones. In order to examine the structure of emotions a multiple correspondence analysis was performed with the following three factors: the situations in each content type (38 levels), the country (4 levels) and the emotion (10 levels). The results found that the structure for all four countries demonstrated a dimension of pleasantness, which is in line with a core affect model of emotion affect (e.g., Russell & Barrett, 1999). Cultural variations were also observed, notably, the location of fear (in relation to other emotions) by US participants differed greatly from those of the other countries, suggesting that the relationship between fear and other emotions for people from the US is unique.

Keywords: Emotion, Culture, Emotional situations, Emotion structure

Cite this paper: Mariko Kikutani, Machiko Ikemoto, James Russell, Debi Roberson, Cultural Influences on the Structure of Emotion: An Investigation of Emotional Situations Described by Individuals from Cambodia, Japan, UK and US, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 20-26. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20160601.04.

1. Introduction

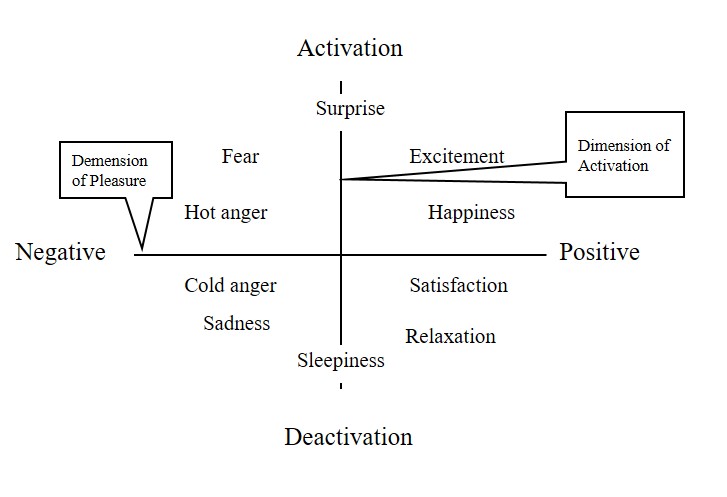

- Cultural variation is one of the most investigated topics in the area of emotion research. Cultural similarities and differences have been observed for a number of emotional experiences such as facial expressions, physiological reactions, and feelings (Mesquita & Frijda, 1992). The present research focuses on cultural variations in the description of emotional events and in the dimensional structure of a set of emotions. The events individuals experience can be categorized as reflecting socially shared meanings or schemata, and defining the connections between the event and certain emotions (see Mesquita & Frijda, 1992 for review). Previous research has identified some universal event types as well as culturally specific ones. Hupka et al. (1985) found two global factors (a threat to an exclusive relationship and self-deprecation) underlying romantic jealousy and envy situations among individuals from seven different countries. This contrasts with the culturally specific example of Japanese people identifying a type “immodesty” for events in which one acts to stand out in a crowd (Lebra, 1983). This method of event coding can be used to assess the presence of an association between an event and an emotion. Event coding, however, is not suited to the measurement of cultural variation in the strength of such associations. For example, events such as “achieving something without relying on others” and “being approved of by others” are both easily identified as representing positive emotions, and so they would be coded similarly across cultures, but the strength of association between the positive emotion and these two events can be affected by cultural differences. The former event may be frequently reported by those from individualistic cultures while the latter may be more commonly reported by members of collectivistic ones (Kitayama, Markus, & Kurokawa, 2000). In order to investigate whether culture influences the association of emotional responses to events the present research asked participants to describe situations in which they would feel a certain emotion rather than asking them to classify given situations. Our participants were from four countries: Cambodia, Japan, the UK and US. The four countries represent individualistic cultures (UK and US) and collectivistic ones (Japan and Cambodia). The present research also investigated cultural differences in the dimensional structure of emotions. Structure is described as discrete categories, dimensions, and hierarchy, and this breakdown generates useful insights into relationships between different emotions (see Russell & Barrett, 1999). The present research focused on the following ten emotions: surprise, happiness, excitement, satisfaction, relaxation, sleepiness, sadness, cold anger, hot anger, and fear, which were identified by Ikemoto and Suzuki (2008) based on a circumplex model (Russell, 1980). The model employs a two-dimensional structure, pleasure and activation, and suggests that various emotions are mapped on and between these dimensions to form a circular structure rather than clusters at the axes (Russell, 1980). This idea was further developed into a core affect model, which describes a mental representation of emotion in terms of a state of pleasure or displeasure (Barrett, 2006a, 2006b; Barrett, Mesquita, Ochsner, & Gross, 2007; Russell, 2003; Russell & Barrett, 1999). The circumplex and core affect models are constructed around factor analyses of self-reported emotions, and multi-dimensional scaling of emotional words, facial expressions and emotional voices (Russell & Barrett, 1999). Similarly, Ikemoto and Suzuki (2008) identified the structure of the ten emotions (see Figure 1) based on the perception of emotional voices. The present research examines whether a similar structure can be observed for descriptions of emotional situations.

| Figure 1. The emotion structure (Ikemoto & Suzuki, 2008) based on the circumplex model (Russell, 1980) |

2. Method

- Participants 82 participants (40 males and 42 females) with a mean age of 33.75 years (SD=7.14) participated in this research. They were from Cambodia (n=21), Japan (n=23), the UK (n=17), and the US (n=21), and all were native speakers of the language of their countries.ProceduresParticipants were instructed to write down situations in which they would feel the following emotions: surprise, happiness, excitement, satisfaction, relaxation, sleepiness, sadness, cold anger, hot anger, and fear. They were asked to write two to five situations for each emotion. The questionnaires were distributed online for participants from Cambodia, the UK and the US while those from Japan answered on paper.

3. Result

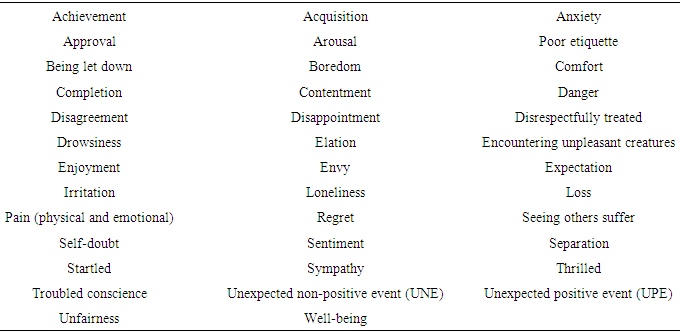

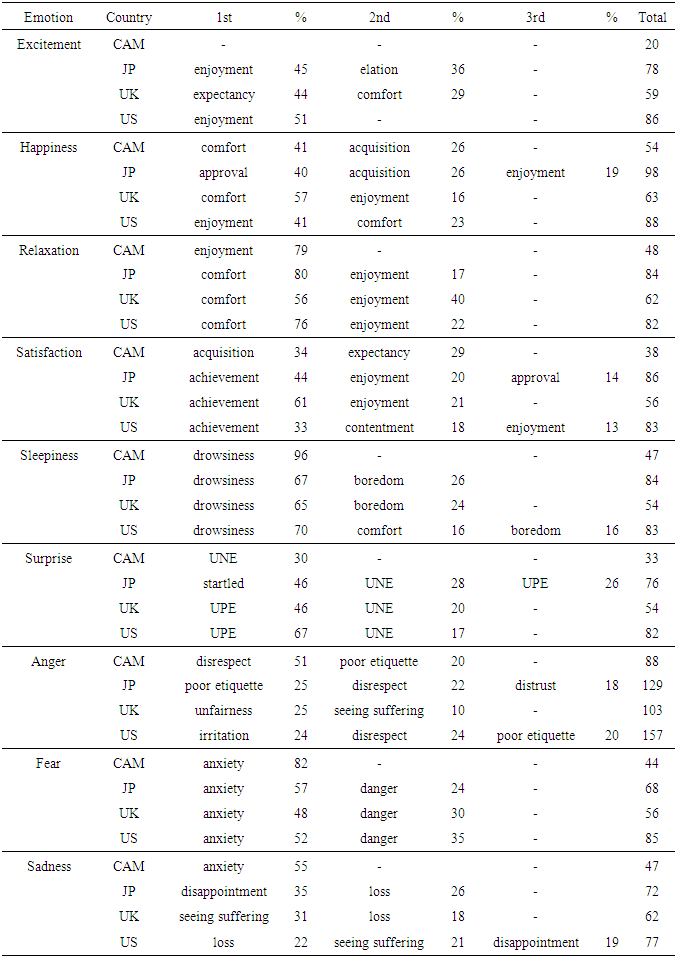

- The number of valid answers made by participants was as follows: US (n=823), UK (n=569), Cambodia (n=374), and Japan (n= 775), totalling 2541 situations. Two researchers classified all the described situations into categories. First, they separately sorted the data according to similarity, and jointly identified 38 common categories. All data were then re-classified into these 38 categories. The agreement for the initial categorization reached 90% of the data, with the remainder being sorted by agreement. Table 1 shows the 38 situation categories.

|

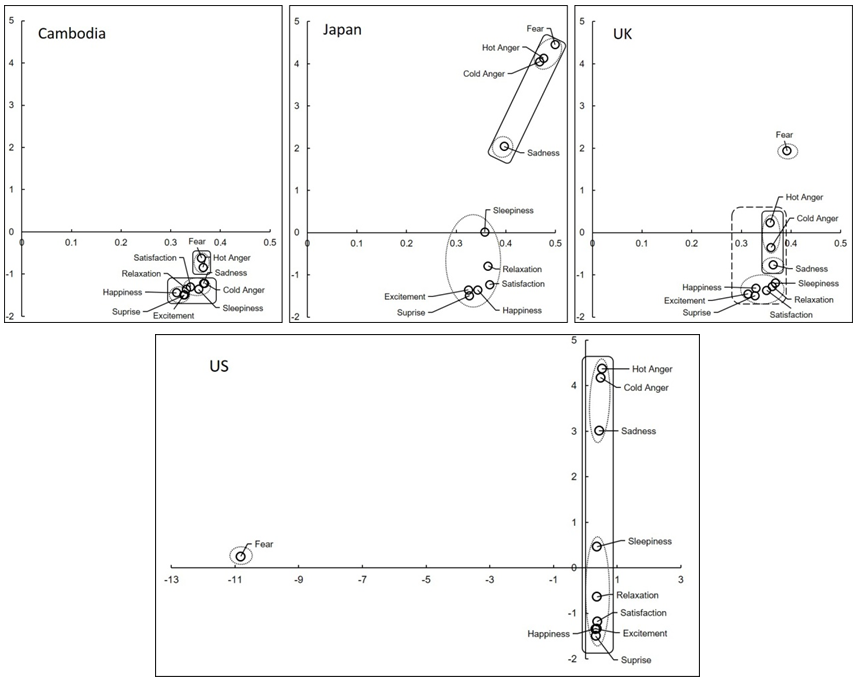

| Figure 2. The emotion structure for the four countries |

|

4. Discussion

- The purpose of the present research was to investigate whether people from different cultures associate emotions with events differently, and whether these differences would be observable in the underlying structure of these emotions. The MCA and cluster analysis, which examined the relationship between emotions and described situations, showed that the emotion structure for the four countries clearly includes a dimension of pleasure. Positive and negative emotions were grouped together for all the countries although the distances between the emotions were varied. This result supported the core affect model, describing that pleasure and displeasure are a universal dimension for the cognition of emotion (Russell & Barrett, 1999; Russell, 2009). Within the positive and negative groups, positive emotions were clustered very closely to each other while individual negative emotions were more distinct. This pattern is identical to the structure found for emotional voices (Ikemoto & Suzuki, 2009), showing a greater degree of qualitative overlap for voices expressing positive emotions.The location of fear for US participants was isolated from all the other emotions, and this gives the US a unique structure. The result indicates that the relationships between fear and other emotions for people in the US are somewhat different from those for people from the other three countries. Fear belongs to the negative emotion group for the data from Cambodia, Japan and the UK, but US fear was located in an area between the positive and negative groups. This means that the fear experienced by the US contains a similar amount of pleasure and displeasure (Russell and Barrett, 1999). This might be because people in the US included thrilling experiences, such as watching horror films or riding a roller coaster, as fearful. The participants from the US reported a higher proportion of active events, both dangerous and thrilling, compared to people from the other three countries. This tendency might have caused US fear to require the second axis to be extended, and if so, the second dimension of the structure might represent the level of activation as in the circumplex model (Russell 1980). It is likely that fear is more action based for the US than other countries, but further research is necessary to determine the qualitative differences of the emotion.Although the present research tested two East Asian and two Western countries, representing collectivistic and individualistic cultures respectively, the cultural differences were not reflected on the structure of emotions. On one hand, the structure for the UK and US are very different despite the shared language, while the UK structure is similar to Cambodian’s in terms of the closeness of emotions. On the other hand, the Japanese structure did not share the clustered features of Cambodian’s and had more similarity to the US. These results imply that similarity and differences in emotion structure may not be determined by the aspects of culture that are classified as collectivist or individualistic. Characteristics of language may be a factor; for example Park (2011) found that Korean emotional words tend to be ambiguous and one word can contain several meanings encompassing positive and negative, while Japanese emotional words are less ambiguous. That the UK and US show very different structures, however, indicates that there are factors other than language involved. One possible factor which can vary across countries even with a shared language and similar culture could be socio-economic situations or country-specific events. These factors may affect the relationship between the event type and the emotion. For example, in Japan as a whole, earthquakes are always a possibility and as a consequence fear tends to be associated with natural disasters. For the US, natural disasters may be more localised danger but the fear of terrorism may be more in the minds of the populous. In this case the quality of fear and the relationship between fear and other emotions may be different for Japan and the US, and may be reflected in their emotional structure. The influence of socio-economic situations was also apparent for the frequently described situation categories.In the frequently described categories we are able to see influences from culture, social situation, history, and language. Cultural influence was most noticeable on happy situations for the Japanese. They feel happiness when they are approved of by somebody else, reflecting collectivistic cultural values over individualistic ones (Kitayama, Markus, & Kurokawa, 2000). Cambodian people strongly associated anger and being treated disrespectfully with a loss of dignity, referred to in Asian cultures as face (Leung & Cohen, 2011). Neither did these two countries associate sadness with other people’s suffering, in contrast to the two western countries. This may be because collectivistic cultures clearly delineate between in-group and out-group and in order to favour in-group members they are less sensitive to the emotions of out-group members (Heine & Lehman, 1997). Social situations and history also played a part. Long-term domestic conflicts in Cambodia seriously damaged their society and economy (Schunert, Khann, Pot, Saupe, Lahar, Sek, & Nhng, 2012), and brought uncertainty to their people’s future. This is reflected on large proportion of anxiety related responses by our Cambodian participants. Influence of language can be seen in Japanese responses for surprise. Because the Japanese word for surprise (odoroki) shares a meaning with “startled” (Morino,1990), 46% of Japanese situations for surprise fell into the startled category, while none of the other countries associated these two in major way. In summary, the emotion structure for Cambodia, Japan, the UK and US commonly showed a dimension of pleasure while maintaining observable variations from each other. The differences in emotion structure did not reflect the individualism/collectivism aspects of culture, but are possibly influenced by the socio-economic situations of each country. Contrasting with event coding research, the present study revealed that associations between event types and emotions can vary between countries even for basic emotions. Culture, language and the socio-economic factors for each country appear to influence the relationships between particular events and emotions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML