-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2015; 5(5): 141-145

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20150505.05

Preliminary Evaluation of a Nine-Step Anger Management Counseling Model: Anger Management Evaluation

Floyd F. Robison

Indiana University School of Education, Indiana University – Purdue University at Indianapolis, Indianapolis, Indiana

Correspondence to: Floyd F. Robison, Indiana University School of Education, Indiana University – Purdue University at Indianapolis, Indianapolis, Indiana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study evaluated Robison’s (2007a) nine-step anger management counseling model. Clients with anger management problems were randomly assigned to a nine-step anger management treatment condition or a waiting list control condition. Clients in the anger management treatment condition exhibited better anger management and lower scores on an anger inventory. Thus, the model appears to have promise as a brief anger management counseling approach. Results of this study are used to formulate questions for further research on ways the model can be used effectively with angry clients.

Keywords: Anger management, Counseling, Psychotherapy

Cite this paper: Floyd F. Robison, Preliminary Evaluation of a Nine-Step Anger Management Counseling Model: Anger Management Evaluation, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 5 No. 5, 2015, pp. 141-145. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20150505.05.

Article Outline

1. Evaluation of a Nine-Step Anger Management Counseling Model

- Problems associated with anger are a significant focus of mental health services in many countries, including the United States (Kassinove & Tafrate, 2002). Robison (2007a, 2007b) created a behaviorally based counseling model that conceptualizes the anger control process as a linear sequence of nine steps. The model differs from other anger management models because steps one through three, and steps five through nine are conducted over one-week period, and step 4 (the decision to commit oneself to using the anger management steps) is processed with step three in a single session. Thus, the entire nine-step process would be completed in as few as eight weeks. If clients can successfully learn to manage their anger in this brief time period, the model would be an efficient, cost-effective intervention compared to other anger management approaches. This preliminary, exploratory study was the first of a series of planned investigations on the effectiveness of the Nine-Step Anger Management model. The study’s purpose was to determine if men and women who completed a four-week counseling program with the model managed their anger more successfully than clients in a control group. Description of the ModelThe Nine-Step model is grounded in cognitive-behavioral theories, particularly those of Beck (1976, 1999) and Meichenbaum (1995). The model proposes that people interact with one another according to a complex set of beliefs. These beliefs are learned over one’s lifetime. Beck (1976) suggested that beliefs are organized into very broad, inclusive beliefs about people and situations generally (e.g., “people who ask for favors cannot be trusted;” “A real man fights when he is confronted.”), and situation-specific beliefs (e.g., “Tom asked me for a favor, he’s taking advantage of me! I ought to hit him!”). Persons’ situation-specific beliefs, also known as self-talk (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977) are consistent with metacognitions and guide their behaviors in those situations (Meichenbaum, 1995). People who are frequently angry and manage their anger poorly tend to engage in negative self-talk though which they tell themselves they are being attacked and must respond aggressively in order to stop the attack (Beck, 1999). In daily life, angry self-talk includes self-statements such as “He’s trying to take advantage of me, no one gets away with that” or, “My wife spends all my money, she’s making me look like a fool. A real man sets people straight when they make him look foolish.” Thus, the model asserts that successful anger management requires people to change their negative self-talk by engaging in the following process: (1) identify the situational cognitions (i.e., self-talk) and underlying metacognitions that lead to angry feelings and aggressive behaviors, (2) create alternative, more positive metacognitions and situational self-talk that would enable them to feel and behave differently in situations that currently make them angry, (3) learn new behaviors associated with their metacognitions and self-talk, and (4) stop their angry self-talk and replace it with the new self-talk by using the nonaggressive behaviors they have learned (Meichenbaum, 1995).This model assists clients in identifying and changing their “angry thoughts,” then deploying their new thinking and positive behaviors through nine structured steps in situations where they find themselves becoming angry. The first three steps help the clients identify and change “angry self-talk.” These steps are as follows: (1) learning one’s physical anger cues, that is, the signs (e.g., perspiration, increased heart rate, throat or chest tightness, fist clenching) that one is becoming angry, (2) identifying angry beliefs (i.e., metacognitions) and situational thoughts that lead to anger in particular situations, and (3) creating new beliefs and situational thoughts in those situations, and new behaviors that would enable one to respond appropriately rather than aggressively in those situations. Step 4 consists of a brief discussion during which clients commit to use the alternate ways of thinking and behaving. (Robison, 2007b) asserts that this step is necessary to impress upon clients the importance of making a conscious commitment to change. The next five steps are used when clients are in a situation where clients recognize that they are becoming angry. The steps are as follows: (5) clients stop what they are doing and saying immediately upon identifying their escalating anger, (6) clients walk away, physically or mentally, from the situation, (7) they think about the alternate thoughts and accompanying behaviors which they committed to use, (8) they call or text a “buddy” with whom they have arranged to contact in situations they have become angry, in order to discuss the situation and be reminded of the alternate thoughts and behaviors to which they committed, and (9) return to the situation at a later time and negotiate appropriately with the others at whom they had the conflict. More detailed descriptions of these steps are found in Robison (2007b). The model may be used in group (Robison, 2007a) or individual (Robison, 2007b) anger management counseling. The model typically is delivered in four, 60-minute weekly counseling sessions (two steps per week), although some clients may require an additional counseling session in order to follow certain steps consistently. Like other anger management approaches, the Nine-Step model is a cognitive-behaviorally based, linear (i.e., carried out in a series of steps) model, though which clients analyze their thoughts in situations during twhicvh they are angry, then change their thinking and accompanying behavior in those situtions. In contrast to other models, this approach proposes that chronic anger can be managed in a relatively shorter time period. Typical models (e.g., give a couple here) require up to six months in order to successfully complete the treatment. The Nine-Step approach requires four to six weeks to complete. If, in fact, the model is successfully completed in as little as four weeks, it would provide a cost-effective alternative to other anger management treatments. HypothesesThis initial study evaluated Robison’s (2007b) assertion that clients who participated in anger management therapy with this model would exhibit significantly better anger management skills after four weeks. Two directional hypotheses were tested, as follows:H1: Participants in the Nine-Step model will exhibit appropriate anger management skills more frequently than participants in a waiting list control group.H2: Participants in the Nine-Step model will obtain lower levels of self-reported anger than participants in a waiting list control group.

2. Method

- ParticipantsParticipants were 20 adult men and women referred to three mental health counseling practices in the Midwestern United States. Physicians referred thirteen clients, and seven were self-referred. Ten participants were male and ten were female. Four participants (two men, one woman) were African-American and four (two men, two women) were Hispanic. Dependent MeasuresTwo dependent measures were used to assess the effectiveness of counseling with the model, as follows:Successfully Managed Anger Incidents (SMAI): Participants were asked to keep a written record of each incident during which they became angry using a form provided by the investigator (Appendix A). The form included spaces for participants to enter the following: (1) location of the incident (e.g., work, the mall, church), (2) who was involved in the incident, (3) a brief description of the incident, in terms of what happened leading up to the incident, the circumstances of the incident itself, what the participant said and did during the incident, and what events occurred immediately after the incident ended. Each fully completed entry constituted an anger incident. The number of anger incidents the participants encountered during a two-week period after completing the final anger management counseling session were used to compute this this variable. In order to determine if participants successfully managed their anger during an incident, two judges independently reviewed the records and rated the participants’ descriptions of their behaviors during the incidents. Judges were trained to rate the descriptions according to the Nine-Step model’s definitions of a successfully managed incident (Robison, 2007b). Incidents were rated as successfully managed if the participants engaged in any of the following behaviors: (1) behaved verbally and nonverbally in ways that would not reasonably be expected to escalate a conflict or induce an aggressive response by anyone else involved in the incident, (2) excused themselves non-aggressively, or (3) attempted to negotiate appropriately with others involved in the incident. Prior to the beginning of the data collection, the raters reviewed 65 journal entries prepared by previous anger management clients. Inter-rater agreement on whether or not the entries met the criteria for a successfully managed anger incident was 0.91. On four entries with disagreement, the judges discussed their ratings with the investigator and reached consensus on the evaluation of each entry.Next, the number of successfully managed anger incidents for a participant was divided by the participant’s total number of anger incidents during the two weeks following treatment completion. This ratio was multiplied by 100 to create the variable successfully managed anger incidents (SMAI). Higher scores represented a higher proportion of incident during which participants successfully managed their anger. Anger Scale: Each participant identified a friend or family member who served as an informant. Informants completed a ten-question anger scale constructed by Robison (2007b) and modified for this study. Items described negative verbal and nonverbal behaviors persons with poor anger management skills exhibit during conflicts. Responses were made on a three-point scale (1: Person never acts this way, 2: Person sometimes acts this way, and 3: Person always or very often acts this way). This scale has been used with clients at the three offices for several years. A preliminary tryout of the scale prior to this study revealed an internal consistency reliability (coefficient alpha) of .87. Lower scores on this scale represented lower anger levels and better anger management. Informants were instructed to rate the participant’s behavior during the two-week period after the fourth anger management session had been completed. The scale is presented in Appendix B. The intake worker told informants for participants in the control condition that the intake worker’s contacts were part of their anger management treatment. Thus, informants were not aware if the participants they rated were participating in the anger management or control conditions. ProcedureTreatment Condition. Ten participants (five men and five women) were assigned randomly to either the treatment or control condition. The treatment condition participated in four, 60-minute, weekly individual anger management counseling sessions according to the session protocols described by Robison (2007a, 2007b). With the exception of step 4 (decision to commit to the model), each step was covered in 30 minutes of one session. Thus, Session 1 covered Steps 1 and 2, Session 2 covered Steps 3 through 5 (Step 4, was addressed immediately after completing Step 3), Session 3 covered Steps 6 and 7 and Session 4 covered steps 8 and 9. Counselors were a male and female therapist who were trained to conduct anger management counseling with this model. Between sessions, participants were instructed to continue studying the steps during the following week and maintain their anger journals. After completing the fourth session, participants maintained their anger journals for an additional two weeks. Journal entries during the two weeks after the counseling ended served as data for the SMAI dependent measure. At the end of the second week after the treatment concluded, informants rated their participants’ anger on the anger scale. Those scores were used as the Anger Scale dependent variable.Control Condition. Five men and five women were assigned randomly to the control condition. These participants agreed to wait six weeks prior to starting the anger management treatment program. This waiting period is not unusually long for the clinics in this study nor is it an unusually long waiting period among mental health agencies in the region. During this period, the participants also maintained anger journals. The intake specialist at each office contacted participants and informants weekly. They obtained general statements about participants’ well-being e.g., “how have you (or, “How has [Name of participant] been doing this week” “Any new concerns?”). Intake counselors were instructed not to provide counseling to the participants, other than to clarify the manner in which the anger journals were to be prepared. Having regular, non-therapeutic contact with research participants on a waiting list is recommended in order to reduce dropouts and maintain contact with persons in order to address any needs that may arise during the waiting period (Mitchell, 2012). These participants received anger management counseling using the Nine-Step model after the data collection was completed.

3. Results

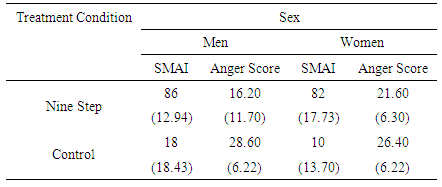

- The dependent variables (Successfully managed Anger Incidents, Anger Scale scores) were analyzed using separate 2 (Treatment Condition) X 2 (Participant Sex) ANOVA. Means and standard deviations for each cell in the design are presented in Table 1.

|

4. Discussion

- Results revealed that men and women who participated in the Nine-Step anger management counseling treatment successfully managed their anger more frequently than clients in the progressive relaxation control group. The outcome of the Nine-step treatment on participants’ subsequent anger clearly varied by participants’ sex. Based on their anger scores, men appeared to exhibit less anger in the Nine – Step treatment condition than women. Possibly, the treatment may enable men and women to improve their anger control but is more effective in changing men’s attitudes that influence them to become angry. This exploratory investigation provides preliminary support for the Nine-Step model’s effectiveness as a brief counseling strategy to improve anger management skills. However, the study has certain limitations that should be addressed in future research on the model. First, the study relies on participants’ own reports of their anger management behavior. The use of self – report measures often is used in counseling outcome research, particularly in exploratory studies on treatment outcomes. Nonetheless, behavioral measures generally are preferred over self-report measures and the evolution of outcome research on this model will necessitate developing such measures. Also, this study included a rather small sample of 20 patients, with five patients in each of the four cells in the experimental design. Although there is no “minimum” cell size in a factorial design, five observations per cell typically provides adequate variance when participants are sampled from a representative population and randomly assigned to treatments (Trochim, 2007). This study was enhanced by selection of participants from multiple mental health clinics in the area and random assignment of men and women to treatment and control conditions. Nonetheless, a larger number of participants in future studies would strengthen confidence in the results. Increasing the sample size should emphasize increasing the racial diversity of the sample. This study included only a small number of African–American and Hispanic participants. There were too few of these participants to enable inclusion of race as an independent variable. In order to for the Nine-Step model to be a viable treatment strategy, it must demonstrate effectiveness for persons of color as well as Whites. Our research team has initiated a study similar to this one in order to assess the outcomes of the model for African-American, Asian-American, Native American, and Hispanic clients. In addition, the literature notes that performance in anger management counseling may vary as a function of clients’ age, with older clients tending to perform better than younger clients. This study did not address the longevity of the positive effects observed for participants in the Nine-Step group. The ultimate goal of a treatment program is to promote long-term changes in attitudes and behavior. Further study of this model will assess the extent to positive change in anger management endure over time. If a brief counseling approach can facilitate lasting change in anger levels and anger management behaviors, it would be welcomed as a cost-effective, efficient alternative to current treatments that often require several months to complete.

Appendix A: Anger Incident Report

- Location of the incident: ____________________________________________________________________________________________Who, beside yourself, was involved in the incident?______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________What happened leading up to the incident (consider no more than the hour before the incident)?______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________What happened during the incident itself? Be as specific as possible. Be sure to describe what you said and did. Use the back of this sheet if you need more space.__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________What happened after the incident was over? Consider only the hour after the incident ended.______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

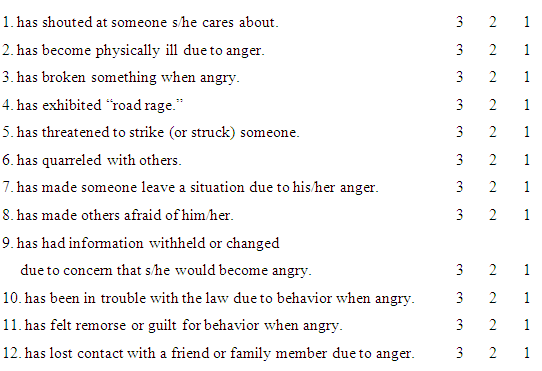

Appendix B: Anger Scale

- Instructions: Please complete this questionnaire for (Name of participant) based on your observations of (his/her) actions and statements during the past two weeks in situations that made (him/her) angry in the past. Read each statement and use the following scale to make your responses:Rate 3 if the person you’re rating always or very often acts this way.Rate 2 if the person you’re rating sometimes acts this way.Rate 1 if the person you’re rating never acts this way. During the past two weeks, this person has:

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML