-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2015; 5(5): 133-140

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20150505.04

Personal Values, Gender Differences and Academic Preferences: An Experimental Investigation

Lovleen Berring, Santha Kumari, Simerpreet Ahuja

School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Thapar University Patiala, Punjab, India

Correspondence to: Lovleen Berring, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Thapar University Patiala, Punjab, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

There is a plethora of information on personal values and career choices which is of great concern to parents, educators, and policy makers. The Self-determination theory shows that personal values and psychological needs are directly linked. The present study emphasizes the impact of personal values on choice of academic disciplines of young adults in the eastern society. It focuses on the comparative study of value orientation of 400 students of two educational fields of different colleges of Punjab, India by using The Aspiration Index. Findings indicate that students in arts/humanities stream score high on intrinsic value orientation and vice versa for business/technical stream. The findings have been discussed, in the light of gender differences along with the transition in value system and subsequent choice of academic discipline.

Keywords: Academic choice, Career Choice, Extrinsic values, Intrinsic values, Value orientation, Gender differences

Cite this paper: Lovleen Berring, Santha Kumari, Simerpreet Ahuja, Personal Values, Gender Differences and Academic Preferences: An Experimental Investigation, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 5 No. 5, 2015, pp. 133-140. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20150505.04.

- Traditional knowledge society had ensured that ethical practices were the integral part of social and personal order of life. It is also well recognized fact that environment and surroundings along with genetic endowments affect the magnitude of human growth and nature. With the fast changing business and environmental scenario the concept of values also underwent continuous evolutionary changes with time. This transition phase has affected the youth worldwide. The curious, vital and self-motivated youth is capable of making potential impact on the future of a nation. Their energies need to be channelized in the right direction in order to make the best out of their capabilities. A career decision guided by a fully functional value system can accelerate the pace of overall human development.Personal Values: Intrinsic and ExtrinsicValues are those personal standards, desirable qualities or principles that individuals set for them to live. These are the broad psychological constructs with implications for both motivated behavior and personal wellbeing that guide the selection or evaluation of actions, policies, people and events (Schwartz, 2006). Values give direction to some of the most important decisions of life including the choice of academic discipline for making a career in it. Thus, to a great extent values determine the quality of life one leads.Several theories have been formulated regarding the various types of values. Self-determination theory of human motivation and personality is concerned with people’s inherent growth tendencies and innate psychological tendencies (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Based on its sub theory, named Goal content theory, Kasser and Ryan (1993) suggested that goals and values fall into two categories: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic values such as self-acceptance, affiliation and community are thought to be inherently satisfying to pursue, as these are directly linked to psychological needs and reflect basic growth tendencies (Kasser & Ryan, 1996). Extrinsic values including financial success, fame and physical appearance are directed by observable external factors such as rewards, punishments or peer/parental pressure (Deci & Ryan, 2000). These can even interfere with the basic need satisfaction, but they do provide some derivatives and indirect strength (Deci & Vansteenkiste, 2004). Value and academic choiceResearchers have studied the value systems of business students (Kasser & Ahuvia, 2002), psychology students (Sagiv & Schwartz, 2000), education students (Vansteenkiste, Duriez, Simons & Soenens, 2006), real estate professionals and management students (Salek, 1988). Studies have found that those who aspire for human services and helping professions including social work, teaching and nursing place less value to status, competitiveness, power and prestige, and more value to people and society, while the reverse is true for mathematics, science, management, business, engineering and technical career aspirations (Jozefowicz, Barber & Eccles, 1993; Salek, 1988; Sagiv & Schwartz, 2000; Brown, 2002; Lupart, Cannon & Telfer, 2004; Davey & Lalande, 2004). Gender Differences in Value Orientation in relation to academic choice Research evidence indicates that gender differences exist in terms of value orientation. Males have a tendency to follow the extrinsic values such as wealth accumulation, earning fame and admiration and are little concerned about social wellbeing and affiliation unlike females (Kasser & Ryan, 1993; 1996; Brown, 2002; Beutler, Beutler & McCoy, 2008). Several cross cultural studies have replicated these results (Ryan et al., 1999; Vansteenkiste et al., 2006; Schmuck et al., 2000).Studies support that males and females have differences in their value orientation due to which they have different curriculum and job preferences. Males value those jobs which give them high status, prestige, power to control others and material wealth, whereas females prefer the jobs which are people or society oriented and let them care and help others (Jozefowicz et al. 1993; Jones, Howe & Rua, 2000). Guided by their aspirations and expectations of jobs males prefer realistic category of jobs including technical, ‘hands on’ activities, and with high anticipated earnings, whereas females chose social category, which includes helping activities, and making a difference in the world (Davey & Lalande, 2004; Duffy & Sedlacek, 2007; Patton & Creed, 2007; Barth et al., 2010).Values: Changing patternsWith the large scale economic development and technological innovation an overall cultural change has been witnessed all over the world. Modernization and economic development is associated with a systematic change in the basic values (Inglehart & Baker, 2000). Over the years the traditional view of gender roles i.e. breadwinner males and homemaker females have also shifted globally (Lease, 2003). Industrialization and urbanization has created new opportunities and role spaces for both men and women, which has further brought a global change in their thinking patterns and preferences (Parikh & Shah, 1991; Hughes, 1995; Davey & Lalande, 2004; Parikh & Sukhatme, 2004). Both males and females have stepped into each other’s shoes by considering novel atypical professional choices (Parikh & Engineer, 2000; Davey & Lalande, 2004; Simpson, 2005). Coincident with the upsurge of professional opportunities, economic development and westernization, there has been a decline and erosion of human values all across the globe leading to harmful effects on mankind (Schmuck et al., 2000; Ryan et al., 1999; Kim, Kasser & Lee, 2003). Since ages, Indian cultural values and goals have been known to be consisted of helping others, respecting others, fulfilling the expectations of significant others, and an interdependent self which shows an inclination towards the intrinsic values (Misra & Agarwal, 1985; Markus & Kityama, 1991; Singhal & Misra, 1994; Levine, Norenzayan & Philbrick, 2001). Attempts have been made to get an insight into the various phases of emerging career of women as mangers and engineers such as their career ambitions, enrolment and out turn in such careers and their phases of transition from home to corporate offices along with the societal shift from agrarian to industrial (Parikh & Shah, 1991; Parikh & Engineer, 1999; Parikh & Sukhatme, 2004). Though studies have been conducted on value orientation of students in western cultures (Kasser & Ahuvia, 2001; Schmuck et al., 2000; Vansteenkiste et al., 2006) but there is a paucity of such research in an eastern culture. Authors have not come across any study that highlights the relationship between the changing pattern of personal values of males and females pursuing different curriculum streams in an eastern culture such as India. This study is unique in its approach because it tries to explore the prevailing trend of core values and life goals of Indian students who opt for typical and atypical academic disciplines, by using The Aspiration Index based on Self Determination theory. In addition to this, the study attempts to investigate the impact of change in the traditional value system affecting the choice of academic discipline amongst males and females. The Present ResearchPeople from different academic disciplines have differences in their value orientation. Individuals who choose Arts and Humanities fields are more focused towards contributing to community and helping others (Davey & Lalande, 2004; Vansteenkiste et al., 2006), whereas the individuals in Business and Technical fields have more concern for wealth accumulation and image (Kasser & Ahuvia, 2002). Women focus on maintaining meaningful and intimate relationships, contributing to community and working for the betterment of society. They aspire to live a meaningful life and learn new things through personal growth. Basically, females believe in satisfaction of basic psychological needs (Beutler et al., 2008). On the other hand, males primarily value materialistic needs such as being financially successful and own expensive things (Duffy & Sedlacek, 2007). They prioritize becoming popular, maintaining a public image and being admired (Kasser & Ryan, 1993; Ryan et al., 1999; Vansteenkiste et al., 2006; Barth et al., 2010; Davey & Lalande, 2004). However, unlike women of older times, women of the present generation in both western and eastern societies are trying to maintain a balance between the home and career (Parikh &Engineer, 1999; 2000; Hakim, 2006). The aspiration of career growth, need to achieve and earn well has led to a change in the choice of academic discipline as well as profession of women (Parikh & Sukhatme, 2004). On the basis of above premises it can be predicted that students of arts/humanities field show more intrinsic value orientation as compared to students of business/technical field. The changing pattern in the value orientation and subsequent academic choices in both males and females are also being investigated.

1. Method

- Participants Sample consisted of 400 students: 200 students from arts and humanities field of the mean age 22.5 years and SD .57 (100 males and females each) and 200 students from business and technical fields of the mean age 21.5years and SD .53 (100 males and females each). Data was collected by means of stratified random sampling from different institutes of Punjab offering these courses. After taking permission from the heads of the institutes for the data collection, undertaking of students was taken to complete the tests related to personal values. Enthusiastic students who willingly completed the questionnaires were appropriately reinforced with pens, notebooks and refreshment at the end of the testing process.MeasuresThe Aspiration Index (AI) A test developed by Kasser and Ryan (1996) was used to measure the intrinsic and extrinsic values. Permission from Dr. Richard Ryan was taken before using the test. The scale consists of 42 items which measures 7 domains of aspirations, broadly covered by two types of value orientation-intrinsic and extrinsic values. AI assesses the relative centrality of particular goals within an individuals’ goal system, which the participants rate on different kinds of dimensions on a 5 point likert scale. The questions are about the goals subjects may have for future. Subjects rate each item twice, firstly by circling how important each goal is to them; secondly, by circling the chances of attaining those goals in future. For scoring, Relative extrinsic value orientation score (REVO) was calculated for both importance and likelihood of goals by subtracting the average of intrinsic item scores from the average scores of extrinsic item scores to differentiate the subjects having high intrinsic values from those having low intrinsic values. Range of the gathered score was from -3 to +3. So, to negate the negative scores and to normalize the data on a scale, a constant of ‘3’ was added to all the ratings. This ensured that all scores were positive. High scores reflected high intrinsic value orientation and low score reflected high extrinsic value orientation. Cronbach alpha of this measure for the sample was .82.

2. Results

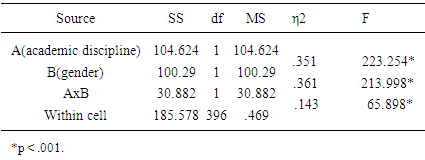

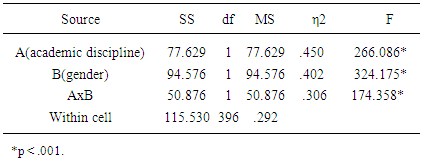

- The data was analyzed using 2x2 factorial ANOVA to find out the effects of academic discipline and gender on value orientation. The analysis of variance for REVO importance yielded the main and the interactions effects as presented in Table 1. Results showed that the main effects of academic field and gender were significant. The main effect of academic discipline yielded an F ratio of F (1,396) = 223.251, p < .001, η2 = .351, indicating that the mean change score was significantly higher for males (M=3.65, SD = .67) than for females (M = 2.66, SD = 1.08). The main effect of gender yielded an F ratio of F (1,396) = 213.998, p < .001, η2 = .361 indicating that the mean change score was significantly higher in students of Business and Technical fields (M = 3.67, SD = .89) than in students of arts and humanities field (M = 2.65, SD = .89). The interaction effect was also significant, F (1, 396) = 65.897, p <. 001, η2 = .143. To get further insight into the data a simple effect analysis was carried out. The main effects of gender were significant for arts/humanities fields, F(1,396) = 257.94, p <. 05 and insignificant for business/technical, F(1,396) = 21.13. The main effects of academic discipline were significant for females, F(1,396) = 265.06, p <. 05 and insignificant for males F(1,396) = 23.24.

|

|

3. Discussion

- In the present study it was proposed that there are differences in value orientations of students belonging to arts and humanities field and business and technical field. The results indicate the confirmation of suggested hypothesis. The Aspiration Index yielded two categories of value scores which were converted into REVO scores. Firstly, REVO Importance scores, that indicated the importance of a particular value or a goal in a person’s life. Secondly, REVO Likelihood scores, that indicated the expectancy/chances of occurrence of those goals in future. Similar pattern of findings emerged for REVO importance of values as well REVO likelihood of values. This is evident from the results that students of business / technical fields give more importance to extrinsic values and expect higher chances of their attainment in future as well. These findings are consistent with previous studies that values play a role in choosing the curriculum field (Schmuck et al., 2000; Brown, 2002; Duffy & Sedlacek, 2007). Vansteenkiste et al. (2006) supports that students of different educational fields vary in value orientations by reporting a difference in aspirations of students pursuing business and education fields. The results can be explained in the light of the increasing focus towards materialistic goals has brought about a change in the value orientation of present generation (Kasser & Ryan, 1996). This craving for material gain and demand for greater riches can be gratified with the help of money making professions such as business and technical careers. We can assume that this is one of the reasons why young adults engage in following the trend for getting admissions in technical and business fields. Another possible reason can be that arts and humanities fields provide more opportunity for community orientation and affiliation such as meeting people, knowing and understanding others, working for society. This explains that people who have intrinsic values pursue helping professions such as psychology, teaching, nursing, social services (Jozefowicz et al., 1993; Ros, Schwartz & Surkiss, 1999; Davey & Lalande, 2004) rather than going for business fields (Kasser & Ahuvia, 2002; Salek, 1988; Vansteenkiste et al., 2006).Murray (1938) contented that environmental forces play an important role in the exhibition of basic psychological/psychogenic needs. He called these forces ‘press’; referring to the pressure they put on us that force us to act. This interaction between individual needs and environmental press motivates an individual to seek out a working environment in which he can express his basic needs and values. So, decision regarding choice of educational stream is dependent on one’s personal value system (Murray 1938; Hall & Lindzey, 1970). Judge and Bretz (1992) also concluded from their study that individuals choose those jobs whose value content is similar to their own value orientation. Krishnan (2008) reported that during the course of management study, students undergo a considerable change in their values, the relative importance of self-oriented values increase whereas the relative importance of other-oriented values decrease. Due to changing societal demands and patterns, material possessions and accumulation of income and wealth has taken a central place in the lives of people. Consequently, this is bringing about a change in value system of the young generation. It can be inferred from the investigated data and the mentioned studies that students belonging to different academic disciplines have differences in their value systems.It is also being confirmed that there are gender differences in terms of value orientation. Females place more importance to meaningful relationships; personal growth and community relationships whereas males are more focused upon earning money, fame, and maintaining a popular image (Schmuck et al., 2000; Niemiec, Ryan & Deci, 2009). College women are more concerned about fulfillment of affiliation needs; whereas men are value the fulfillment of achievement needs (Schultheiss & Brunstein, 2001; Pang & Schultheiss, 2005). Gender roles and consistent normative expectations also explain the existence of gender differences according to which females perform domestic roles and males are involved in economically productive activities (Wood & Eagly, 2002). Women are expected to be communal i.e. friendly, unselfish and interdependent whereas men are expected to be agentici.e. independent, masterful, competent and self-assertive reflecting feminine and masculine socialization (Kray & Thompson, 2004; Ferriman, Lubinski & Benbow, 2009). Hakim (2006) summarizes many of the research findings by stating that overall men and women differ in work orientation and labor market behavior which is basically linked to broader differences in life goals and the relative importance of values such as competitiveness versus consensus seeking and the relative importance of family life and careers. Therefore we can infer from the above mentioned studies and the investigated data that males and females endorse different value systems.Moreover, it can also be observed from the simple effect results of the academic discipline that overall; the females of both academic disciplines have more inclination towards intrinsic values in comparison to males. The reason can be traced back to biological theories as well as sociocultural theories. Biological differences in both sexes lead to various physiological, cognitive, affective and behavioral differences in them. From sociological perspective, women and men have been assigned different gender roles right from birth; they are brought up differently; having different experiences, which develop their stereotypic conceptions of gender, leading to different self-schemas (Kohlberg, 1966; Martin & Halverson, 1981; Leaper, Anderson & Sanders, 1998). Parents encourage feminine behavior, politeness and nurturance of their daughters and masculine and independent behavior of their sons (Leaper Leve, Strasser & Schwartz, 1995; Pomerantz & Ruble, 1998; Leaper & Friedman, 2007; Gelman, Taylor & Nguyen, 2004). As per traditional roles, women are expected to be more caring, nurturing, socially responsible, empathetic and more predisposed towards interpersonal goals and relationships (Carlson, 1971; Stein & Bailey, 1973; Bem & Allen, 1974; Skitka & Maslach, 1996; Dunn, 2002; Parsons & Bales, 2014). Thus, due to the genetic impact and sociocultural influence, overall, the women have more intrinsic values.However, when we compare the females of both academic fields, it is being observed that females of arts/humanities are more oriented towards the intrinsic values, whereas the business/technical females are comparatively less intrinsically oriented. This shows a shift of values towards the extrinsic orientation in case of women involved in new emerging non-traditional business/technical streams. The possible explanation is the emergence of women in non-traditional professions due to growing industrialization, urbanization, social legislation and awareness (Masood, 2011). With this changing trend, the women of new generation gives equal weightage to family and job; and have become more career oriented and ambitious to rise up the organizational ladder (Parikh & Engineer, 2000; Budhwar, Saini & Bhatnagar, 2005). Kapoor, Bhardwaj and Pestonjee (1999) have also reported that women in managerial posts are highly ambitious for holding high positions and to get on the top. This reflects a gradual generational change in the female value system. A study conducted by Parikh and Sukhatme (2004) shows that females seek financial growth through technical professions such as engineering. Though the genetic makeup of females and the sociocultural influences make them more predisposed towards intrinsic values, but females are now adopting new perspectives while choosing their options. Studies report more masculine traits and low affiliative needs and goals of women pursuing atypical careers (Davey & Lalande, 2004; Trigg & Perlman, 1976, Twenge, 1997). The present also shows that females who have stepped into ‘male dominated’ business and technical fields exhibit a shift towards extrinsic value orientation unlike females of arts and humanities fields.Results also reveal that males of arts and humanities fields show an inclination towards intrinsic value orientation unlike the males of business and technical fields. Studies show that the societies with greater gender equality witness a reduced gap in values of males and females, where both sexes attribute less importance to materialistic values like power, achievement, security and more to benevolence and universalism (Schwartz & Rubel, 2005, 2009). Such results might be an indicator of the gradual increase in gender equality in the patriarchal society such as India. This can be one of the explanations why males have started opting for intrinsically oriented feminine fields. Chusmir (1990) investigated the internal factors such as men’s background, attitude, values and intrinsic needs and external factors such as family and societal influence behind the males’ choice of feminine careers and educational fields. Lemkau (1984) found that men in atypical professions had experienced death, divorce or separation in the family, had distant relationship with father, and were more influenced by women in their career decisions. Such factors actually sensitize the males to nurturant and emotional capabilities, which ultimately pave way for choosing sex atypical careers. Researchers report that ‘female dominated’ careers offer the males greater job flexibility, allows time for family and other priorities such as physical and emotional health, freedom to choose less stressful and aggressive job opportunities to prove self-fulfillment and providing help to others (Pleck, 1985; Kimmel,1987; Lease, 2003; Resurreccion, 2013) and thus they are also reported to be high on affiliative needs, tender mindedness and have low adherence to traditional sex roles (Lemkau, 1984; Davey & Lalande, 2004). This is evident in the above mentioned studies that males who choose careers such as arts and humanities have started prioritizing intrinsic values. Overall the results indicate an inclination of students of arts/humanities fields towards intrinsic values. Whereas, the business/technical fields that offer more money, fame and prestige attract the young minds for the same reasons. Individuals assume to confirm the societal norms, even their parents want their wards to follow the trend, to do what the majority of youth is doing. But the extrinsic values bring with itself lower global adjustment, mental health, social productivity, predisposition to behavioral disorders (Kasser & Ryan, 1993), low quality of life, conflictual relationships, greater drug use (Kasser, 2000; Kasser & Ryan, 2001) and more chances of substance use (Vansteenkiste et al., 2006). Similar findings have been reported across cultures such as US, South Korea (Kim, Kasser & Lee, 2003), Germany (Schmuck, Kasser & Ryan, 2000) and Russia (Ryan et al., 1999). Immediate gratification of materialistic gains does not give long term happiness. Maslow (1971) reports an overlap between the intrinsic values and B-needs. These are the being-needs, due to which people progress farther than the basic needs and help in the satisfaction of top most needs in the hierarchy including self-actualization. Thus intrinsic values help one in achieving the meta-needs. Extrinsic goals are contingent upon other’s approval, and may lead to distress, lower wellbeing, threatened security, less focus on growth and ultimately more concentration on money, image and status (Maslow, 1954; Sheldon & Kasser, 2008). This study tries to explain that psychological satisfaction and sustainable happiness is the ultimate aim of life which can be achieved by following one’s inner voice, not that of the world around. If one is intrinsically focused towards intrinsic values, that individual will lead a more satisfactory life.The focus towards materialistic goals has resulted in a change in the value orientation of present generation (Kasser& Ryan, 1996). There are generational differences in values, older generations laid more importance on altruistic and welfare values and younger generations prefer prestige values, hedonistic and stimulation seeking (Kasser & Ryan, 1993; Lyons et al., 2005). Conditions from society, family environment, and various other factors gradually lead to such drastic changes. This study also describes that with the large scale economic development and technological innovation, professional choices and value orientation of young generation of India is changing.The results of this study are consistent with the prior research but they contribute new dimensions to the literature. For instance, it compares the students of two different academic disciplines in terms of core personal values named intrinsic and extrinsic as suggested by Self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Most of the studies reported in the literature have taken into consideration only the work values of employees in different careers. Another important implication is that the knowledge of appropriate career choices can intensify the establishment of education curriculum based programming. Additionally, it also reveals the tendency of changing pattern of values in an eastern society emerging along with the upsurge of women empowerment and participation in atypical careers. The emerging endorsement of extrinsic aspirations suggests the need to control the erosion of values. It will help to channelize the young minds to maintain a work life balance and follow the appropriate path by giving importance to intrinsic values rather than just gratifying the need for money and social recognition. It throws light on quest for love and happiness; and focuses on motivating young individuals to maintain equilibrium between the increasing greater societal demands and a psychologically healthy quality of life. It lays emphasis on values and curriculum choice which can be helpful for parents, teachers and counselors to channelize human potential to the utmost. The study will help to probe reasons for changing gender patterns and understand the developmental change.The present study does have a few limitations. It would be valuable to control the possible intervening variables affecting the results such as birth order of the subjects, occupation of their parents and family patterns. Secondly, such studies can be conducted across cultures to investigate the gradual change in the value orientations of young adults. In addition to this, it is very essential to study the impact of this period on the overall development of young adults as they confront many challenges and changes in this critical phase. Thus, lifespan developmental studies in future research would be helpful in highlighting the transition in value system and subsequent choice of academic discipline over a period of time. It is believed that this study may represent a starting point for young adults and professionals interested in understanding the transition in values and curriculum choices.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML