-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2015; 5(2): 21-25

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20150502.01

Wait, Bring It Back! ‘Expectancy to Eat’ Moderates the Effectiveness of Food Cues to Improve Mood

Gregory J. Privitera, Kayla N. Cuifolo, Quentin W. King-Shepard

Department of Psychology, St. Bonaventure University, St. Bonaventure, NY, USA

Correspondence to: Gregory J. Privitera, Department of Psychology, St. Bonaventure University, St. Bonaventure, NY, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Recent data from neurobiological and behavioral studies indicate that food images can enhance positive mood without requiring food intake. However, it is unclear if expectations to eat a food impact the longer-term benefits observed using food images in behavioral studies. For this reason, in the present study we tested the hypothesis that expectations about eating a food can influence the effectiveness of food cues to enhance positive mood. Participants were randomly assigned to groups in which mood was measured at baseline, 5-min, and 10-min while a plate of 5 cookies or an image of those cookies was present. Expectation to eat and taste was also measured. At 5-min, the food cue was removed. Participants were either allowed (expectation to eat was met), or not allowed (expectation to eat a food was not met) to eat one cookie before the plate was removed. A control group was shown an image of the cookies only. Results show that mood increased in all groups at 5-min. For groups who viewed an actual food, eating a small portion at 5-min sustained high mood at 10-min. Thus, using a food image has longer-term benefits without requiring increased caloric intake to sustain increases in mood.

Keywords: Buffer Effect, Mood, Food Images, Mood Therapy

Cite this paper: Gregory J. Privitera, Kayla N. Cuifolo, Quentin W. King-Shepard, Wait, Bring It Back! ‘Expectancy to Eat’ Moderates the Effectiveness of Food Cues to Improve Mood, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 21-25. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20150502.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Emotional regulation is related to eating behavior [1-3], with food intake regulated by emotion in order to promote and sustain emotional well-being [4, 5]. Consumption of “comfort” foods, which are often high in fat and sugar, have been linked to the rising rates in obesity [6, 7], and yet also lead to improved emotional states [8]. Recent data show that viewing food images can enhance positive mood states [9, 10], which has led to the suggestion that viewing food images (instead of eating foods) can possibly be applied as a therapy to promote mood without increased caloric intake, especially for those with depressive mood [11].One possible limitation to the generalizability of implementing a food image therapy is the extent to which positive mood changes persist after the food images are removed. Viewing images of “comfort” foods can lead to increased responsiveness in brain regions involved in regulating reward-guided behavior [12, 13] and can improve mood [9]. Drawing images of these foods can likewise enhance mood [10]. For these types of experiments, measures of mood change are typically recorded while the images are presented or immediately after they are removed.At present, there is no distinction in the literature regarding whether real foods or food images are used as the mood-enhancing cue [11]. However, it is possible that participants may have different expectations about the cue depending on the type of food cue used to enhance mood [14, 15]. The expectancy learning theory [15] posits that if participants have different expectations about a cue for which they have a learning history (such as a food cue), this could influence long-term changes in mood. Based on this theory, participant expectations are a cognitive mechanism that can influence subsequent changes in mood in this case. One expectation participants likely have in response to a food cue is the expectancy to eat the foods [11]. With an image of a food, an expectancy to eat the food cue is not realistic, whereas this is a truly realistic expectation with an edible food as the mood-enhancing cue.Using food images or edible foods may have the unintended consequence of a negative contrast effect [16-18], which could result from the contrast between seeing “comfort” foods (positive condition) and having them removed (a relatively negative condition in contrast to seeing the foods). If simply removing a food/food image were the negative contrast, then we expect that mood will reduce after a food or food image is removed. However, if the expectation of eating a food were the negative contrast, then we expect mood to decrease only when an edible food is removed, and not when a food image is removed [19].In addition, if expectancies about eating a food were the cognitive mechanism by which mood stays high even after a food is removed, then we would further expect that if participant’s were allowed to eat a small portion of the food prior to its removal, then this could buffer against any decrease in mood because the expectation of eating the food was met [11, 15]. In the present study, we tested this possibility and further tested short- and longer-term outcomes of mood change to determine the most effect strategies for using foods and food images to enhance positive mood even after a food cue is removed.

2. Method

- A completely randomized between-subjects experimental design was used with three groups observed.

2.1. Participants

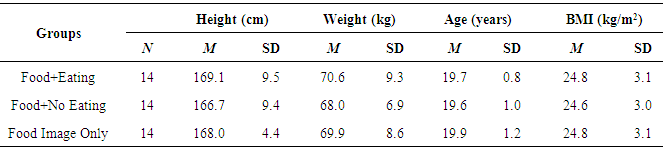

- All participants were adults who signed a written informed consent. The St. Bonaventure University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the protocol for this study. 42 undergraduate students (18 men, 24 women) were recruited using university classroom visits and sign-up sheets. Participant characteristics were (M±SD) age (19.7±1.0 years), weight (69.5±8.3 kg), height (167.9±7.8 cm), and BMI (24.7-±3.1 kg/m2). Table 1 summarizes these characteristics by group assignment, as described further in the Procedures section. In an initial screening phase, participants reported that they were in general good health with no physical or doctor diagnosed food allergies, medical conditions including pregnancy, or dietary restrictions. They were told during this initial screening phase not to eat within two hours of the study. Because hunger states can influence food intake [20, 21], only participants who did not eat within two hours of the study were allowed to participate.

|

2.2. Procedures

- Participants were observed one at a time in a kitchen setting. In a separate room, participants were seated and signed an informed consent. Upon signing the consent form, participants completed a preliminary demographic survey, and rated their current mood and hunger using an adapted version of the affect grid [22] with coded scales for hunger from 1 (not hungry at all) to 9 (very hungry), and for mood from 1 (very negative mood) to 9 (very positive mood). Upon completing these measures, a participant was brought into the kitchen and sat at a table with a plate of five cookies on it.Using a completely randomized experimental design, participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: In Group Food+Eating, participants were told “Please face forward, do not eat or touch the food on the table, and the study will begin soon.” After 5 minutes, participants rated their hunger/mood using the same affect grid, and rated how much they expected to eat the food on the table on a scale from 1 = very low to 7 = very high (to check that participants with an edible food on the table indeed had a greater expectancy to eat the food). For participants in this group, they were told at this time that they could eat one cookie-each participant tasted and rated the cookie on a 7-point scale from 1 = dislike very much to 7 = like very much; all participants consumed the cookie. Five minutes later, participants again rated their hunger/mood on the affect grid. For participants in Group Food+No Eating, the procedures were the same, except that they were never told or allowed to eat the food at 5-min; instead, after the first 5 minutes, the food was simply taken away. These two food groups allow for a comparison to see if being allowed to eat a small portion of a food can buffer against a possible negative contrast effect from seeing the food, but not being allowed to eat the food. In a third comparison group, Group Food Image Only, participants were treated the same as Group Food+No Eating, except that only an image of the cookie was present on the table, and not actual cookies. This comparison was a group in which there was no realistic expectation that participants would be able to eat a food (because only an image of the food was presented, and not an edible food). For the two groups that did not eat a cookie, they were given one cookie after mood was recorded at 10-min and asked to taste and rate it on the 7-point scale so that the taste of the cookie could be compared between groups. All participants were then debriefed and dismissed.

2.3. Data Analyses

- A mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. The between-subjects factor was Groups, and the within-subjects factor was Time of Rating (baseline, 5-min, 10-min). The dependent variables were hunger and mood ratings. Ratings of expectation to eat and the taste of the cookie were also compared between groups. Sex was initially included as a factor, but excluded after it showed no significance with effects reported here. Planned comparison one-way within-subjects ANOVAs were computed to evaluate interaction effects. A Bonferroni procedure was used to correct for experimentwise alpha. A Tukey’s HSD was used to analyze main effects and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were drawn. The null hypothesis under evaluation for each group was that the difference score in the population was zero. An effect was identified if the CI did not envelop zero. All tests were conducted at a .05 level of significance.

3. Results

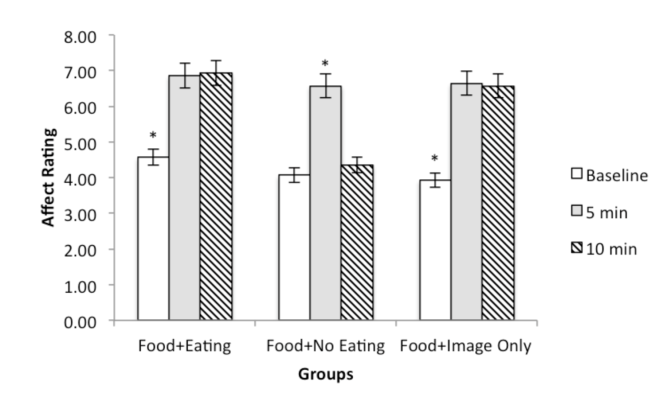

- With mood as the dependent variable, a significant main effect of Time was evident, F(2, 78) = 23.01, p < .001 (R2 = .37), with mood (M±SD) higher at 5-min (6.69±1.52) and 10-min (5.95±2.38) compared to baseline (4.19±2.38). A significant Groups Time of Rating interaction was evident also evident, F(4, 78) = 2.59, p = .04 (R2 = .12). As shown in Table 1, one-way ANOVAs by group at each level of Time of Rating were significant for each group. For Group Food+Eating, F(2, 26) = 9.22, p = .001 (R2 = .42), participants had a significant increase in mood at 5-min (95% CI 0.69, 3.88) and at 10-min (95% CI 0.76, 3.95) compared to baseline. For Group Food+No Eating, F(2, 26) = 10.61, p < .001 (R2 = .45), participants had a significant increase in mood at 5-min (95% CI 1.20, 3.77) but not at 10-min (95% CI -0.74, 1.31) compared to baseline. For Group Food Image Only, F(2, 26) = 8.74, p = .001 (R2 = .40), participants had a significant increase in mood at 5-min (95% CI 1.26, 4.17) and at 10-min (95% CI 0.60, 4.69) compared to baseline.Hunger ratings showed no significance (p > 70 for all tests), which was expected given the minimal duration of the study and minimal food consumed. Ratings (M±SD) were similar at baseline (5.38±2.17), 5-min (5.50±2.52), and 10-min (5.40±2.13). Taste ratings of the cookie also showed no significance between groups (p = .96), with ratings (M±SD) being similar in Group Food+Eating (5.50±1.09), Food+No Eating (5.43±1.34), and Food Image Only (5.36±1.74). As expected, ratings of expectation to eat the cookie were significantly different between groups, F(2, 39) = 37.33, p < .001 (R2 = .65). Post hoc tests showed higher ratings (M±SD) to eat the food for groups with an edible cookie on the table (Food + Eating: 4.4±1.3; Food + No Eating: 4.6±1.5) compared to the group with the food image (1.4±0.5). The two groups presented with an edible cookie did not differ in their ratings of expectation to eat the cookie (p = .20).

4. Discussion

- The utility of strategies that allow participants to view foods and images of foods as a method to enhance positive mood was tested. Results showed that if participants were placed in the presence of a high calorie food (i.e., a cookie), then allowing them to eat a small portion of that food upon removing it can buffer against possible negative contrast effects and mood remains high 5-min after the food was removed. Not allowing participants to eat any portion of the food results in a decline of mood back to baseline 5-min after the food was removed. Using an image of a food was effective at enhancing positive mood a 5-min and 10-min. Given that no food is consumed when a food image is used, this may thus be a preferred strategy as a therapy to enhance positive mood without the increased caloric intake.Based on the expectancy learning theory [15], participant expectations about a food cue could influence positive mood change. Based on this theory, if simply removing the food image influences changes in longer-term mood, then mood should have returned to baseline in all groups at 10-min, but this outcome was not observed. As an alternative: If participant expectancies to eat a food influenced changes in mood, then we would expect a negative contrast to result from a failure to meet that expectation. The pattern of data observed in this study is most consistent with this interpretation. The two groups that had an edible food on the table showed increased mood at 5-min, but at 10-min mood remained high only for the group allowed to eat a small portion of the food (expectation to eat met), and returned to baseline-levels for the group not allowed to eat the food (expectation to eat not met). Given that both edible food groups reported similar expectancies to eat the food, this outcome suggests that when an edible food is used as a mood-enhancing cue, longer-term increases in mood are most effective when participants are allowed to eat some portion of that food. With food images, participants had little expectancy to eat a food, and mood remained high at 10-min even though participants in this group never ate a cookie. Many recent studies show that when participants view food cues, there is a corresponding increased responsiveness in brain regions that regulate mood [12, 13] and increased behavioral changes in mood [9, 10]. The present study builds on the neurobiological and behavioral evidence by identifying how the need to meet participant expectancies to eat a food (a cognitive mechanism) can also impact changes in mood. Studies like these further show promising results that could lead to potential therapies for people with depression, as has been previously suggested [11]. While a non-depressed sample was observed here, participants with depression should have lower baseline mood levels, thereby leading to greater sensitivity to observe positive mood changes with food cues using similar procedures to enhance mood. Such an at-risk group should be observed because interventions to improve mood may be most beneficial for this group [11, 23].In the present study, participants who viewed an edible food showed a buffer effect—showed a sustained longer-term mood increase—when allowed to eat one-fifth of the portion of cookies presented. Whether the buffer effect would also be observed if participants ate less cannot be determined here. Also, only one food type (cookies) was used in this study. Whether the observed pattern of results will generalize to other food types cannot be determined either. These possible constraints can and should be tested. At present, however, the results are most consistent with the conclusion that expectancy to eat a food is a cognitive mechanism influencing the effectiveness of using foods to enhance mood. These findings extend a growing body of research suggesting that using food images of high calorie foods can be a potentially effective therapy to improve positive mood without increased caloric intake.

5. Conclusions

- Recent data from neurobiological and behavioral studies [9-12] are unclear regarding the possibility of whether or not expectations to eat a food can impact the longer-term benefits of using food images to improve positive mood. The present study confirms that expectations about eating a food can, in fact, influence the effectiveness of food cues to enhance positive mood. Results show that when the expectation to eat is not met (i.e., when an edible food is used and participants are not allowed to eat the food), mood returns to baseline levels only 5 min after the food is removed. No such expectation to eat needed to be met when just a food image was used and mood remained high at 10-min. Thus, expectations to eat can influence longer-term mood enhancement. The results further suggest that using a food image to enhance positive mood may be the preferred behavioral therapy to enhance positive mood because it has longer-term benefits to improve positive mood without requiring caloric intake.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This study is dedicated on loving memory to Col. Richard L. Shepard. Relationships are the ocean in which we find meaning in our lives. In this way our connections with others are truly substantial. Though you have gone from us you will never be forgotten.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML