-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2014; 4(6): 229-239

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20140406.04

Behavioral-Cognitive Inhibition Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Cognitive Behavior Therapy Developed from the Behavioral-Cognitive Inhibition Theory

Nenad Paunovic

Department of Psychology, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

Correspondence to: Nenad Paunovic, Department of Psychology, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

A first outline of a new cognitive-behavior therapy program for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is presented with regards to its underlying theories and treatment components. It is based on the behavioral-cognitive inhibition (BCI) theory for PTSD (Paunović, 2010) and is named Behavioral-cognitive inhibition (BCI) therapy. The treatment program is presented descriptively session by session. The program rests on the following main blocks: (1) overview of the whole treatment program and normalization of PTSD symptoms in terms of the BCI-theory, (2) the development of narrative stories of valued life event memories, (3) emotional processing of valued life event memories, (4) cognitive processing of dysfunctional trauma-, pre-trauma and posttrauma beliefs central in the maintenance of PTSD, (5) exposure inhibition that consists of (i) emotional processing of valued life event memories, (ii) a single imaginal exposure to central trauma memory details, and (iii) repeating the emotional processing of valued life event memories, and (7) identifying current most valued life areas and utilizing valued narrative stories, emotional processing of valued life event memories and behavioral activation in valued directions.

Keywords: Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, Behavioral-Cognitive Inhibition Therapy, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Valued Narrative Stories, Emotional Processing, Exposure Inhibition, Dysfunctional Beliefs, Behavioral Activation

Cite this paper: Nenad Paunovic, Behavioral-Cognitive Inhibition Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Cognitive Behavior Therapy Developed from the Behavioral-Cognitive Inhibition Theory, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 4 No. 6, 2014, pp. 229-239. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20140406.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The behavioral-cognitive inhibition (BCI) theory was first developed in order to conceptualize posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [1]. In this article a cognitive-behavior therapy for PTSD is presented that is named Behavioral-cognitive inhibition (BCI) therapy. The BCI therapy is tailored to the DSM-V criteria for PTSD [2], and developed from the BCI theory. The BCI therapy program consists of elements described next.

1.1. Normalization of PTSD Symptoms in Terms of the BCI-theory

- The PTSD symptoms are normalized in terms of the BCI-theory. The purpose is to educate the client about PTSD symptoms with the aim of normalizing the PTSD symptoms from the client’s perspective.

1.2. Valued Narrative Storytelling

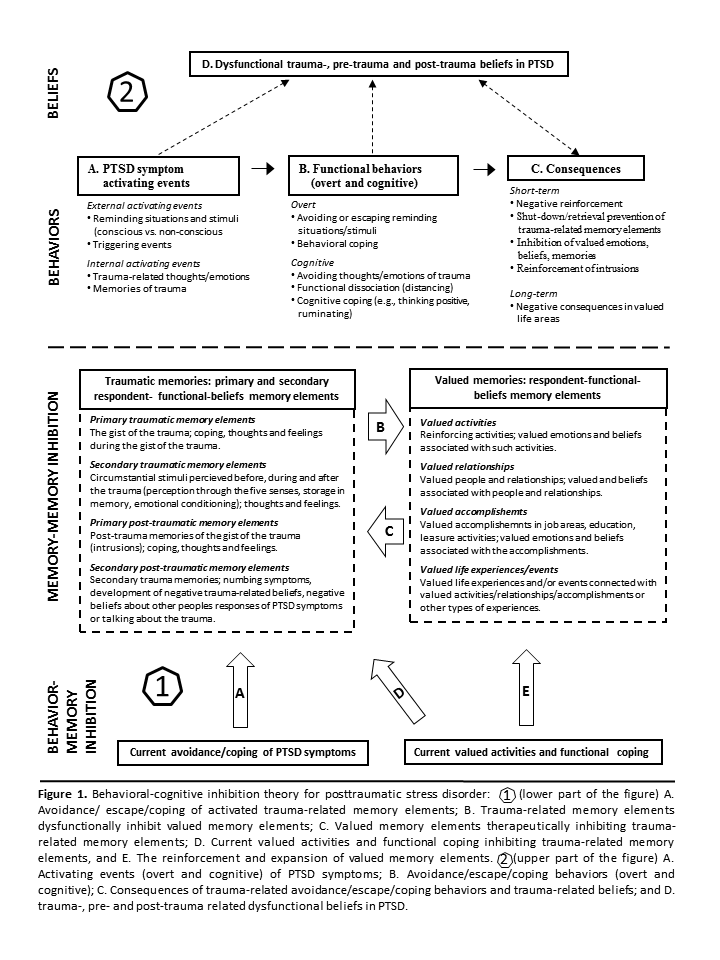

- The aim is to counter overgeneralized positive memories in PTSD through repeated re-telling of valued life event memories. Overgeneralized positive memories in PTSD are counteracted by developing specific valued life event stories. A second aim of valued narrative story telling is to help the individual to focus on what is most valued in life in order to start to plan and engage in (or expand the engagement of) valued life activities. A third aim is to use the information from these stories in order to dispute dysfunctional beliefs in PTSD. A fourth aim is to utilize the information from valued life stories in order to inhibit central trauma memory elements. Positive autobiographical event memories are overgeneralized in PTSD, i.e. are difficult to retrieve [3, 4]. Difficulties in retrieving overgeneralized autobiographical memories in PTSD may contribute to the maintenance of PTSD [4]. Overgeneralized autobiographical memory is an important predictor in the time course of PTSD [5]. Overgenerality in PTSD has also been linked with deficits in social problem solving, suggesting a role in symptom maintenance [6]. In addition, a decline in overgeneralized memories following cognitive-behavior therapy appears to correspond with a reduction in overgeneral memories [7]. Furthermore, Ehlers and Clark [8] state that “…the re-experiencing symptoms are isolated memory fragments that are triggered by matching cues and that they are experienced as if things were happening in the ´here and now´ because they are not integrated with other autobiographical information”. One way to view such a theoretical proposition is as follows: (a) the activation of positive autobiographical event memories helps the client to get access to un-integrated memory information that is incompatible to the meaning of the trauma and PTSD symptoms, and (b) valued narrative story telling is one means to activate such memories. See examples of memory details that have been extracted from valued life event memories in the lower-right part of figure 1.

1.3. Emotional Processing of Valued Life Event Memories

- The purpose of this part of the treatment is to emotionally process central details of most valued life event memories in order to (a) counter numbing symptoms, (b) get access to experiential information that can be utilized as corrective information in relation to trauma-, pre-trauma and posttrauma dysfunctional beliefs in PTSD, and (c) utilized in order to inhibit central trauma memory elements. In this part of the treatment central memory elements of valued life event memories are identified and imaginally relived. Examples of the content of central valued event memories are depicted in the lower-right part of figure 1.

1.4. Cognitive Processing of Dysfunctional Beliefs in PTSD

- Trauma-, pre-trauma and post-trauma dysfunctional beliefs are identified and cognitively processed. Such cognitions are conceptualized in terms of (a) themes of danger, trust, intimacy, control and self-esteem [9], (b) guilt cognitions [10, 11], (c) anger cognitions [12, 13], (d) betrayal, sadness, loss, helplessness and hopelessness schemas [14], and (e) conceptualizations from CBT-models for PTSD such as trauma-related appraisals of PTSD symptoms and post-trauma events [8], and erroneous associations primarily related to danger and incompetence beliefs [15]. After the identification of central trauma-, pre-trauma and post-trauma dysfunctional beliefs that are considered important in the maintenance of PTSD, the client is to practice cognitive techniques [16]. The latter consists of the utilization of challenging questions and erroneous thought patterns in order to dispute dysfunctional beliefs that maintain PTSD. As illustrated in figure 1 central trauma-, pre-trauma and post-trauma dysfunctional beliefs can be traced to (a) the daily dysfunctional interpretations and meanings of PTSD-related stimuli, behaviors and consequences as depicted in the upper part of the figure, and (b) beliefs whose development can be identified from central life event memories of (i) the primary traumatic event that generates PTSD symptoms, (ii) other traumatic events that have contributed to the development of dysfunctional beliefs in PTSD, and (iii) other negative life events that have contributed to the development of other dysfunctional beliefs that maintain PTSD.

1.5. Exposure Inhibition of the Traumatic Memory

- The aim of exposure inhibition is to accomplish an inhibition of central trauma memory elements by emotionally processing valued memory elements. This treatment component consists of the following procedure: (a) the client is to repeatedly and continuously re-tell and be instructed to remember the central details of one’s most valued life event moments before the implementation of a single imaginal exposure to central trauma memory details. Emotionally processing valued emotions before imaginal trauma exposure counteracts numbing symptoms and increases the tolerance to trauma exposure, (b) during imaginal exposure the client is to re-tell the traumatic event in detail once in order to activate the trauma memory and to prepare for an integration into the valued event memory network, and (c) the client is to repeatedly and continuously re-tell and be re-told by the therapist the central details of one’s most valued life event moments. The purpose is to inhibit the central trauma memory elements (e.g., see Paunović, 1999, 2002, 2003, 2011) so that they can become integrated into the valued memory network. The emotional processing of valued life event memories includes remembering the event, the perceived details of the event that were encoded through the five senses, and the concomitant emotions and beliefs. Also, these memory elements constitute information that can be used in order to cognitively process dysfunctional trauma-, pre-trauma and post-trauma beliefs in PTSD. In order to consolidate the exposure inhibition the client is to (i) listen to the audio tape of the session in its entirety as often as possible, and (ii) conduct daily in vivo exposure. If the exposure inhibition process has been conducted successfully during the session, the in vivo exposure is expected to activate the newly formed memory network in which the trauma memory has been incorporated within the valued event memory network. The inhibition of central trauma event memory elements by valued event memory elements is depicted in the lower part of figure 1, by the arrow “C”.

1.6. Valued Behavioral Activation

- Valued behavioral activation is implemented and guided by the valued narrative stories and the emotional processing of valued life event memories. The client is to utilize the parts of the valued narrative stories that are considered to be the most important and possible to behaviorally engage in within the present life situation. I.e., the valued narrative stories are analyzed in terms of what is most important to the client to engage in at the present moment in life. These most valued parts for the present life situation are to be re-told as a story with the purpose of increasing the problem-solving choices to the individual. The emotional processing of these most valued life stories can be utilized in order to increase the motivation to engage behaviorally in one’s most valued directions. The last part of this treatment component is to help the client plan and implement the engagement in theses most valued behavioral activities [21, 22].

2. Behavioral-Cognitive Inhibition Therapy for PTSD: A Preliminary Treatment Protocol

- Here is a preliminary outline of the behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy for PTSD that has been developed from the behavioral-cognitive inhibition theory.

2.1. Session 1 (120 minutes)

2.1.1. Start Recording the Session

- Instruct the client that the session will be audio-recorded, and that the recorded material will be given to the client as homework to listen to until the next session. The client is instructed to bring the audio-recording device to the next session.

2.1.2. Present the Rationale and Overview of the Treatment Program

- (a) Present the rational and an overview of valued narrative story telling.(b) Present the rational and overview of emotional processing of valued life event memories.(c) Present the rational and overview of cognitive therapy for trauma-, pre-trauma, and post-trauma beliefs in PTSD.(d) Present the rational and overview of exposure inhibition.(e) Present the rational and overview of valued behavioral activation utilized trough valued narrative stories, emotional processing of valued life event memories and the planning and implementation of valued behavioral activation.

2.1.3. Normalization of PTSD Symptoms

- (a) Describe common symptoms and related psychopathology symptoms in PTSD.(b) Identify the client’s most disturbing PTSD symptoms and discuss these with the client.(c) Discuss the meaning of client’s PTSD symptoms from the client’s perspective, the nature of the distress and the consequences of symptoms in valued life areas.

2.1.4. Probe for the Clients Understanding of the Treatment Program

- (a) Ask the client (or if a group each individual) to summarize the understanding of the whole treatment program and the normalization of PTSD symptoms.(b) Discuss the parts that were not well understood or not covered by the client.(c) Use socratic questioning and psycho education as needed in order to help the client to summarize the whole treatment program and the normalization of PTSD symptoms.(d) Resolve eventual remaining misunderstandings as comprehensively as possible.

2.1.5. Homework

- Instruct the client to:(a) Listen at least twice to the recorded session until the next session.(b) Read an information sheet that describes the whole treatment program at least once until the next session.(c) Read the information sheet Common symptoms after traumatic events, to register own symptoms and to register what has been learned after reading and discussing common symptoms in PTSD.(d) To register what (if) is not understood about the treatment program, the normalization of trauma symptoms.(e) To bring the recorded device and all registrations to the next session.

2.2. Session 2 (120 minutes)

2.2.1. Review of Homework

- (a) The client hands over the recorded device to the therapist, and the recording of this session is started. If the audio-recording device has not been brought back, start recording the session on another device.(b) Ask the client to reflect on thoughts and feelings about the listening of the recorded session that was listened to since the last session.(c) The client (or each individual in a group) presents one’s understanding of all the treatment components wherein potential misunderstandings may appear.(d) The therapist corrects eventual misunderstandings and educates the client about the misunderstood parts.

2.2.2. Introduce Valued Narrative Story Telling

- (a) Present to the client the purpose and procedure of valued narrative story telling. First, explain how the intrusion symptoms numb the client to positively respond to current valued behavioral activities and memories. Explain the nature of positive overgeneralized autobiographical memories, how valued narrative story telling can increase the specificity of these memories and in the long-term decrease PTSD symptoms. Secondly, explain that the trauma memories are separated from valued life event memories. Thirdly, describe that the valued narrative story telling will activate the valued life event memory network that will help the client to integrate these memories with the trauma memories during the treatment program.(b) Instruct the client to write down a short note on one’s most valued life experiences in the following life areas: valued relationships, valued accomplishments or skills, valued activities, valued appreciations / affectionate responses from others, trustworthy individuals, intimate moments with life partners, self-efficacy events, self-esteem inducing events, and other valued life events. Use the valued narrative storytelling sheet for that purpose (see Appendix A).(c) Instruct the client to choose one experience in each of the above areas if possible and to describe the most valued event in each area as an event or life story.(d) Instruct the client to present a story of the chosen most valued narrative stories.(e) The therapist helps the client to create a streamlined narrative for each valued narrative story. Include both external events as well as thoughts and feelings.

2.2.3. Homework

- (a) Give the client the recording of the session to listen to at least twice until the next session.(b) Instruct the client to write a detailed story of each chosen valued narrative and to bring the written material to the next session.

2.3. Session 3 (120 minutes)

2.3.1. Review of Homework

- (a) The client hands over the recorded device to the therapist, and the recording of this session is started. If the audio-recording device has not been brought back, start recording the session on another device.(b) Ask the client to reflect on thoughts and feelings about the listening of the recorded session that was listened to since the last session.(c) The client reads aloud each of the written valued narrative stories once, and reflects on the thoughts and feelings that comes into the clients mind.

2.3.2. Emotional Processing of Valued Life Events

- (a) Firstly, explain the purpose of the emotional processing of most valued life event memories. The purpose in this part of the treatment is to provide experiential information that can be cognitively processed in relation to trauma-related dysfunctional cognitions during the remainder of the treatment, counter numbing symptoms and increase the exposure tolerance to intrusion symptoms of PTSD.(b) Instruct the client to provide the most central event details of each of the most valued life stories that were written down during homework and the former session. The central event details should include the memory details encoded and stored through the five senses, the event itself, other people’s behaviors, one’s own behavior as well as one’s own thoughts and feelings.(c) Make notes of the most central details of each valued life event.(d) The client is instructed to make oneself comfortable, to close the eyes, and to imaginally relive each valued life event in detail for about 5-10 minutes. The therapist repeats to the client the written down most central valued life event details and asks the client to focus on these details repeatedly for a prolonged time. Alternately, the client is asked to provide more details that are incorporated into the same procedure. If other thoughts intrude into the clients mind the therapist helps the client to stay focused on the most central valued life event details by the same procedure.

2.3.3. Homework

- (a) Give the client the recording of the session to listen to at least twice until the next session.(b) Instruct the client to write down eventual new details of the valued life event memories that are listened to and to bring the material to the next session.

2.4. Session 4 (90 minutes)

2.4.1. Review of the Homework

- (a) The client hands over the recorded device to the therapist, and the recording of this session is started. If the audio-recording device has not been brought back, start recording the session on another device.(b) Ask the client to reflect on thoughts and feelings about the listening of the recorded session that was listened to since the last session.(c) The client reads aloud each of the written down added details that were remembered during the listening of the most valued life event memories.

2.4.2. Cognitive Processing of Dysfunctional Beliefs in PTSD

- (a) Present the role of cognitive processing of dysfunctional beliefs in PTSD. Probe for the client’s understanding of the model and resolve misconceptions.(b) Instruct the client to fill out the form Dysfunctional beliefs after traumatic events (see Appendix B).(c) Review the A-B-C sheet with the client. It consists of three parts: A-an activating event that sets of dysfunctional beliefs (first row), B-the beliefs that have been set of by the activating event (second row), and C-the consequence of the belief (i.e., emotions and behaviors, third row).(d) Go through an example with the A-B-C sheet of one of the clients dysfunctional beliefs. Register activating events in the first row. The purpose here is to teach the client how to identify internal and external activating events that set of dysfunctional beliefs.(e) Instruct the client to register the dysfunctional belief that has been set of by the activating event in the second row. After that, educate the client about the difference between thoughts and feelings, and about the relationship between the activating events and thoughts.(f) Instruct the client to register the consequences in the third row of the A-B-C sheet. Then ask the client to summarize the written down consequences. After that, educate the client about the emotional and behavioral consequences of dysfunctional thoughts. Ask the client to include both emotional and behavioral consequences in the third row.(g) Educate the client about the function of safety and avoidance behaviors in PTSD. Safety behaviors prevent the individual from testing dysfunctional beliefs. Avoidance and escape behaviors shuts down the trauma-related memory, the fear of current innocuous threat stimuli, and leads to negative reinforcement (explain in simple language).(h) Instruct the client to summarize how the A-B-C sheet should be filled out with the reviewed example. Discuss eventual misconceptions or gaps in the summary.

2.4.3. Homework

- (a) Give the client the recording of the session to listen to at least twice until the next session.(b) Instruct the client to fill out the A-B-C sheet when distressing negative emotions are experienced at least once daily (provided that such responses occur).(c) Instruct the client to review each sheet and to reflect on the relationships between activating events (A), beliefs (B), and consequences (C).(d) Instruct the client to bring all the registered A-B-C sheets to the next session.

2.5. Session 5 (90 minutes)

2.5.1. Review of the Homework

- (a) The client hands over the recorded device to the therapist, and the recording of this session is started. If the audio-recording device has not been brought back, start recording the session on another device.(b) Ask the client to reflect on thoughts and feelings about the listening of the recorded session that was listened to since the last session.(c) The client presents the filled out A-B-C sheets and reviews the most distressing or important incidents. Help the client to correct any faults in the registrations and discuss eventual misconceptions or gaps in them.

2.5.2. Introduce the Challenging Questions Sheet

- Introduce The challenging questions sheet [16] to the client, explain how it is used and resolve eventual misunderstandings.

2.5.3. Introduce Faulty thought Patterns

- (a) Introduce Faulty thought patterns [16] to the client and review all of the faulty thought patterns in the Faulty thought patterns information sheet with the client.(b) Instruct the client to summarize the faulty thought patterns and correct eventual misunderstandings.

2.5.4. Introduce the Disputation of dysfunctional beliefs Sheet with an Example

- Educate the client about the Disputation of dysfunctional beliefs sheet by choosing a dysfunctional belief to cognitively process. In the first row the activating event is registered. In the second row the dysfunctional belief is written down. Then the dysfunctional belief is cognitively processed with the Challenging questions sheet and disputed with the answers from this sheet in the third row. Next, the dysfunctional belief is reviewed with regards to faulty thought patterns that are written down in the fourth row. After that a new belief is formulated in the fifth row/upper box. Lastly, the emotional and behavioral consequences of the new belief are formulated in the fifth row/lower box. The behavioral consequences should include a decrease in the use of safety and avoidance/escape behaviors. Help the client to identify safety/avoidance/escape behaviors and to counteract them.

2.5.5. Homework

- (a) Give the client the recording of the session to listen to at least twice until the next session.(b) Instruct the client to fill out the Disputation of dysfunctional beliefs sheet at least once daily as conducted with the example during the session.

2.6. Session 6-7 (90 minute)

2.6.1. Review of the Homework

- (a) The client hands over the recorded device to the therapist, and the recording of this session is started. If the audio-recording device has not been brought back, start recording the session on another device.(b) Ask the client to reflect on thoughts and feelings about the listening of the recorded session that was listened to since the last session.(c) Instruct the client to review the filled out Disputation of dysfunctional beliefs sheet. Help the client to correct eventual faults in the registrations.

2.6.2. Exposure Inhibition

- Describe the purpose and the procedure of exposure inhibition of central trauma memories. The purpose is to inhibit as many central trauma memory elements as possible with the help of the emotional processing of valued life event memories. The procedure is as follows:(a) Instruct the client to close the eyes, make oneself comfortable, and use the information from session 3 when the emotional processing of valued life event memories was conducted. Conduct this part of the session in the same manner as during session 3. Repeat the details from the most valued event memories to the client and ask the client to be an active participant in the process when additional memory details are remembered. Each valued life event memory is imaginally relived for about 5-10 minutes. Chose the most valued life event memories for this process. It is advisable that these memories constitute different themes or areas so that different types of functional beliefs are activated and/or developed. Conduct this process for about 30 minutes.(b) Conduct a single imaginal exposure of the trauma with the client. That is, a shortened version of imaginal exposure to the trauma [15]. The imaginal exposure should usually take 5-10 minutes or until the trauma event narrative has been re-told once in detail. Probe for central details of the traumatic event. The purpose is to activate the central trauma memory elements in order to inhibit them in the next part of the session and/or between the sessions.(c) Conduct an emotional processing of valued life event memories as during the first part of the session for about 30 minutes. The valued life event memory elements become integrated into the trauma memory network and inhibits them.

2.6.3. In Vivo Exposure

- Describe the purpose and the procedure of in vivo exposure to the client [15] and add how this is supposed to work out in terms of the BCI-theory. Plan with the client how in vivo exposure is going to be conducted (preferably once daily or as often as possible). See if the client can be confronted with the most distressing situations immediately, or if moderately distressing situations are going to be confronted first. Ask the client to stay in each situation between 40-60 minutes, or until the anxiety or fear diminishes at least 50-70 %. Use SUDs (Subjective Units of Distress) to measure the level of anxiety or fear before, during and after in vivo exposure (0 = no anxiety/fear, 50 = moderate anxiety/fear, 100 = extreme anxiety/fear). Plan the implementation of in vivo exposure so that safety and avoidance behaviors are dropped. The reason why in vivo exposure to most distressing situations may be viable for many clients is that in vivo exposure in this context has a different theoretical rational compared to standard in vivo exposure. In this context it is assumed that the exposure inhibition during the session has developed an inhibitory memory network in relation to the trauma that may help the client to immediately confront the previously most distressing in vivo exposure situations.

2.6.4. Challenge Dysfunctional Beliefs

- Instruct the client to continue to challenge dysfunctional beliefs with the help of the Disputation of dysfunctional beliefs sheet as conducted before.

2.6.5. Homework

- (a) Give the client the recording of the session to listen to at least twice until the next session.(b) Instruct the client to conduct in vivo exposure at least twice between 40-60 minutes until the next session.(c) Instruct the client to dispute dysfunctional beliefs by the Disputation of dysfunctional beliefs sheet as conducted before.

2.7. Session 8-9 (90 minutes)

2.7.1. Review of the Homework

- (a) The client hands over the recorded device to the therapist, and the recording of this session is started. If the audio-recording device has not been brought back, start recording the session on another device.(b) Ask the client to reflect on thoughts and feelings about the listening of the recorded session that was listened to since the last session.(c) Instruct the client to present and reflect upon the in vivo exposure homework.(d) Instruct the client to review the filled out Disputation of dysfunctional beliefs sheets. Help the client to correct eventual faults in the registrations, and cognitively process the material.

2.7.2. Exposure Inhibition

- The client is instructed to conduct the exposure inhibition process as during the previous session. This time, the emotional processing of valued life events should take about 10 minutes before and 10 minutes after trauma exposure, and the single trauma exposure should take about 5-10 minutes.

2.7.3. Valued Behavioral Activation

- Instruct the client to choose the most important parts of the valued narrative storytelling and the emotional processing of valued life events from all sessions that represent the most valued behavioral activities. Then help the client to plan to engage in most valued behavioral activities in the present. Identify eventual safety and avoidance behaviors that may pose as obstacles. Help the client to plan to cope successfully in the relevant situations. Lastly, set goals with the client on how the plan should be implemented.

2.7.4. In Vivo Exposure

- Plan together with the client the next in vivo exposure exercises and instruct the client to stay in the situations between 40-60 minutes, or until the anxiety or fear diminishes at least 50-70%. Use SUDs to measure the level of anxiety or fear before, during and after in vivo exposure. The client also prepares for how to block any safety and avoidance behaviors during the in vivo exposure.

2.7.5. Challenge Dysfunctional Beliefs

- Instruct the client to continue to challenge dysfunctional beliefs with the help of the Disputation of dysfunctional beliefs sheet as conducted before.

2.8. Only in Session 9 (the last 15 minutes)

2.8.1. Review Treatment Progress and Find Areas for Further Improvement

- (a) Review with the client what has been accomplished with regards to each of the components of the treatment program: valued narrative storytelling, valued emotional processing, cognitive techniques, exposure inhibition, in vivo exposure and valued behavioral activation.(b) Review shortly in which areas the client needs to focus on future therapeutic work and how this is going to be planned and implemented.

2.8.2. Homework

- (a) Give the client the recording of the session to listen to at least twice until the next session.(b) Instruct the client to conduct in vivo exposure at least twice between 40-60 minutes until the next session.(c) Instruct the client to dispute dysfunctional beliefs by the Disputation of dysfunctional beliefs sheet as conducted before.(d) Instruct the client to implement valued behavioral activation according to the treatment plan.

2.8.3. Say Goodbye to the Client and Communicate a Sincere Wish for Further Improvement

3. Discussion

- The behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy for PTSD that has been presented in the current article is based on the behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy [1]. It consists of the following parts: normalization of PTSD symptoms, valued narrative storytelling, emotional processing of valued memories, cognitive techniques, exposure inhibition, in vivo exposure and valued behavioral activation. The package of techniques constitute an integrated approach that has been specifically developed from the behavioral-cognitive inhibition theory presented in fig. 1.Since the purpose of the present article is only to present and describe the recently developed behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy for PTSD, no systematic review of evidence-based therapies for PTSD in relation to this therapy has been conducted. A more systematic review of evidence-based approaches for PTSD, primarily exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy, would take up to much space and compromise the descriptive purpose of the present article. However, such a review is warranted in the future if the utility of the behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy becomes successfully applied by other psychologists and psychotherapists in addition to the author. That is, the behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy is yet to be rigorously tested as a treatment for PTSD in clinical settings.The main limitations of the behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy are as follows:(a) This treatment protocol has not yet been clinically applied by other psychologists or psychotherapists besides the author. However, the purpose of this article is to function as a guideline to other psychologists and psychotherapists in order to test the clinical value of the behavioural-cognitive inhibition therapy for PTSD.(b) The relative efficacy of each treatment component is unknown or whether they operate in interaction with each other. The purpose of the content and the structure of the presented treatment program in this article is to describe how it has been applied in recent clinical work with PTSD patients by the author with success.(c) The behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy includes commonly used procedures in CBT for PTSD such as psychoedcucation/normalization, exposure, behavioral activation and emotional/cognitive processing. However, these components/techniques are utilized differently in relation to new treatment components for PTSD (valued narrative story telling and emotional processing of valued life moments) as compared to evidence-based treatment protocols for PTSD.Another possible critique of this treatment package is that it may consist of too many treatment components. According to this position this could render such a treatment difficult to teach and to implement because there are too many components to keep a track on. However, such a view is based on a component argumentation that may be appropriate with regards to some treatments such as stress inoculation training (SIT) [24]. SIT consists of the following components: (a) breathing retraining, (b) relaxation training, (c) role-playing successful coping in anxiety provoking situations, (d) thinking about and changing behaviors by successfully coping in stressful situations after going through the entire situation in imagination, (e) learning to talk to oneself by recognizing negative or unhelpful statements of themselves and replacing them with more helpful internal “talking”, and (e) stopping negative thoughts. SIT was not developed from the emotional processing theory as exposure therapy was. SIT is based on managing anxiety-provoking situations and can be considered a coping technique therapy consisting of multiple components. Also, the thought stopping technique may be counterproductive because the avoidance of trauma-related stimuli is considered to be a maintaining factor in PTSD.The behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy is not based on an anxiety management paradigm. Rather, it is based on the behavoral-cognitive inhibition theory and the following aims: (a) developing valued narratives in order to become experientially more aware of one’s valued directions in life, (b) emotionally process valued life event memories in order to process emotions incompatible to the trauma, (c) utilize the valued memories in order to cognitively process trauma-related beliefs and inhibit central trauma memories, and (d) become highly motivated to implement valued behavioral activation. Thus, the whole treatment package is theory-driven and the treatment components are highly interconnected. Furthermore, since a significant proportion of the treatment package focuses on valued memories and valued behavioral activation, it ought to be much more motivational-inducing than only techniques whose purpose is to manage anxiety in the short-term. Thus, the author proposes that the behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy will not constitute a multi-component problem since: (a) several of the treatment components share the same theoretical rational (valued narrative story telling, emotional processing of valued life events and valued behaioral activation), and (b) because of the former it may be viewed as consisting of three main components: valued based interventions, trauma-focused interventions, and cognitive techniques.Another relevant topic to discuss is proposed mechanisms in evidence-based cognitive-behavioral therapies for PTSD. In cognitive processing, both an exposure component and cognitive techniques are included. However, the exposure component consist only of written accounts. In a randomized study the full protocol was compared with two other protocols that either consisted of written accounts only and cognitive therapy alone [24]. The written account didn’t add to the efficacy of the cognitive component, and the written account alone was inferior to cognitive therapy alone. Thus, by focusing on changing the meaning (i.e., dysfunctional beliefs in PTSD) that maintain PTSD, the cognitive therapy alone was able to effectively treat PTSD and associated psychopathology.In exposure therapy for PTSD it is proposed that emotional processing is the main mechanism of change [15]. Emotional processing is defined as being emotionally engaged during imaginal and in vivo exposure exercises of the trauma memory and feared trauma-inducing situations. However, it has also been proposed that the main mechanism of change in exposure therapy is the change of meaning of the trauma and central cognitions that are proposed to be involved in the maintenance of PTSD. An indication of emotional processing is habituation. That is, decreases of anxiety or fear within and/or between sessions as a result of exposure. However, habituation is not a mechanism, but only an indication of anxiety/fear decline over time. In fact, a lot of cognitive restructuring may be conducted after the exposure component during the sessions when the exposure process is discussed. The client may then utter dysfunctional cognitions that can be discussed and worked through.To summarize, the main mechanisms of change that are considered to be involved in evidence-based cognitive-behavioral therapies for PTSD are (a) emotional processing of the trauma memory, and/or, (b) a change of meaning of the trauma.In behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy the following mechanisms may be responsible for changing the trauma memory and a recovery in PTSD: (a) a change in valued memories from overgeneralized memories to the development of concrete valued stories [4], (b) emotional processing of valued life moments that inhibit numbing symptoms [20], (c) inhibition of the trauma memory elements by the emotional processing of valued life memories. The mechanism in exposure therapy is inhibition, not extinction [25], (d) valued behavioral activation that inhibit numbing symptoms, and (e) a change in meaning of valued memories, the capacity to emotionally process valued emotions, dysfunctional beliefs in PTSD, the trauma memory and valued behavioral activities. Thus, a multi-component mechanism approach is herewith presented.It is appropriate to first test the behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy for PTSD in a series of case studies. The purpose is to get enough clinical experience in order to adjust the theory and treatment protocol so that the next step can be planned and implemented.The next step is to test the behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy with an evidence-based therapy for PTSD. Since exposure therapy is regarded as the cognitive-behavior therapy with the strongest evidence in the treatment for PTSD, it is suggested that it is compared to the behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy in a randomzied controlled trial. In such a trial it is of utmost importance to ensure that the treatment integrity is maximized for both conditions. It is also important to include a wait-list control condition. Firstly, it is hypothesized that the behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy will be equally effective in treating the intrusion symptoms in PTSD as exposure therapy. Secondly, it is hypothesized that the behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy is going to be more effective in treating the numbing symptoms and the non-fear related dysfunctional beliefs that are supposed to maintain PTSD, e.g. the type of beliefs that currently constitute a part of the DSM-V criteria of PTSD. It is crucial to control for that exposure therapy does not contain any cognitive interventions that may effectively change dysfunctional beliefs in PTSD except those that are related to the exposure interventions. That is, the post-exposure discussion at the end of the sessions should only be devoted to discussions about aspects directly related to the exposure interventions (i.e., fear-related cognitions). They should not contain any discussions or manipulations that are related to non-fear/anxiety related cognitions in PTSD. Thirdly, it is hypothesized that the behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy (a) will be viewed by the client’s as much more important for them for their future life in terms of valued directions, (b) that valued memories will be significantly more detailed and concrete than after exposure therapy, (c) that the clients will engage in significantly more valued behavioral activities than in exposure therpay, and (d) that the behavioral-cognitive inhibition therapy will be viewed as significantly more attractive and less distressing than exposure therapy.

Appendix A

- Valued narrative storytelling sheet Instruct the client to read each statement below and to write down events on separate sheets of paper that illustrate one’s most valued life experiences in each of the following life areas:1. Valued relationships: “I value most the following relationships in my life…”2. Valued accomplishments or skills: “I value most the following accomplishments or skills in my life…”3. Valued activities: “I value most the following activities that i have participated in in my life…”4. Valued appreciative responses from others: “I value most the following appreciate responses from others in my life…”5. Valued affectionate responses from others: “I value most the following affectionate responses from others in my life…”6. Valued loving moments with significant others: “I value most the following loving moments with significant people in my life…”7. Valued trustworthy individuals: “I value most the following trustworthy individuals in following ways…”8. Valued intimate moments with life partners (current and/or past): “I value most the following intimate moments with my current or former life partner…”9. Valued intimate moments with friends: “I value most the following intimate moments with friends…”10. Valued self-efficacy events: “I value most the following events in terms of that i handled them effectively…”11. Valued self-esteem related events: “I value most the following events that have given me most self-worth in life…”12. Other valued life events: “I value most the following events in following ways…”

Appendix B

- Dysfunctional beliefs after traumatic eventsPlease read each question and rate it on the left with a number on a 0-100 scale (see below). After each rating, describe how you think about each type of thought.0 = not at all correct50 = moderately corrrect100 = totally correct1. _____ The world is a completely dangerous place.My thoughts: _______________________________2. _____ I will be dangerously harmed.My thoughts: ________________________________3. _____ People are not trustworthy.My thoughts: ________________________________4. _____ I cannot trust myself.My thoughts: ________________________________5. _____ I don’t have control over my daily life.My thoughts: ________________________________6. _____ I don’t have control over my feelings and symp-toms.My thoughts: ________________________________7. _____ I have a low self-esteem.My thoughts: ________________________________8. _____ People think about me in a negative way.My thoughts: ________________________________9. _____ I think negatively about other people.My thoughts: ________________________________10. _____ It was my fault that the trauma event occurred.My thoughts: _______________________________11. _____ It was other peoples fault that the traumatic event occurred.My thoughts: ________________________________12. _____ I am unable to be close to other people.My thoughts: ________________________________13. _____ I am unable to feel good about myself.My thoughts: ________________________________14. _____ I am unable to feel positive emotions.My thoughts: ________________________________

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author wishes to acknowledge the many years of encouragement and positive reinforcement from professor Sten Rönnberg that has influenced a spirit of creativity and faith very important in this type of developmental work. A remarkable influence from a behavior therapist that has eventually led to the present article despite that many years has passed since he encouraged many of my ideas in a conservative academic climate.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML