-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2014; 4(6): 214-222

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20140406.02

Comparative Effectiveness of Self-Management, Emotional Intelligence and Assertiveness Training Programs in Reducing the Potentials for Terrorism and Violence among Nigerian Adolescents

Ayodele Kolawole Olanrewaju1, Sotonade Olufunmilayo A. T.2

1Research and International Cooperation, Babcock University Ilishan, Ogun State, Nigeria

2Prof. in Counselling Psychology, Department of Educational Foundations & Management, Faculty of Education, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, Ogun State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Ayodele Kolawole Olanrewaju, Research and International Cooperation, Babcock University Ilishan, Ogun State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Youth involvement in organized armed crimes has been on the increase especially in a nation like Nigeria with millions of jobless youths. This study investigated the effect of self-management, emotional intelligence and assertiveness training programs in reducing the potentials for terrorism and violence among Nigerian adolescents. A quasi experimental pretest, control group research design of 3x2x2 factorial matrix type was used for this study. Gender (male and female) and locus of control (internal and external) used as moderating variables were considered at 2 different levels along with two (3) experimental groups. The study participants were one hundred and eighty (180) Senior Secondary 2 students randomly selected from 3 coeducational secondary schools from three different Local Government Areas in Remo educational block of Ogun State, Nigeria. One standardized instrument was used in collecting data while analysis of covariance was used to analyze the generated data. Results show that all the treatment programmes (SM = 20.981 and 1.901; EQ = 21.009 and 1.687; AT = 22.046 and 1. 418) were effective in fostering the reduction of adolescents’ potentials for terrorism and violence but self-management was found to be most effective. The study also revealed that both gender and locus of control of participants combined to interact with the treatment to affect participants’ potentials for terrorism and violence. Results showed that male participants benefit more from self-management and assertiveness training programs while the female benefit more from emotional intelligence training. Also, all the treatment packages work more on the individual internal LOC compared to their external LOC. Based on the findings; it was recommended that the treatment packages could be used as veritable tools in equipping adolescents with necessary skills to help the youths live a worthy life that will bring about better future and peaceful co-existence among the people of the world.

Keywords: Self-management, Emotional intelligence, Assertiveness training, Potentials, Terrorism, Violence, Nigeria, Adolescents

Cite this paper: Ayodele Kolawole Olanrewaju, Sotonade Olufunmilayo A. T., Comparative Effectiveness of Self-Management, Emotional Intelligence and Assertiveness Training Programs in Reducing the Potentials for Terrorism and Violence among Nigerian Adolescents, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 4 No. 6, 2014, pp. 214-222. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20140406.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- All over the world today, terrorism has been perceived as criminal acts, which are considered to be at odds with social, morals and common decency, or to be damaging to the interests of the community, as it is the case with the hijacking of passenger planes, hostage taking of the innocents for purposes of blackmail, the planting of bombs at large gathering, the mining of railway lines for purposes of protest demonstration, subversion or sabotage, the undertaking of reprisals by some countries against the population of others, the victims of which are innocent persons (Kashima, 2003, and Moghaddam, 2005, cited in Tatar, Amram & Kelman, 2010). Terrorism is not just a perceived phenomenon in Nigeria; it is real and felt all over the country- state, intra-state, or international. It is real because all the factors that precipitate terrorism are patently present coupled with the fact that Nigeria is economically and politically unstable. Ayodele (2012) and Ogundiya & Amzat, (2008) rightly noted that in Nigeria today, the threat of terrorism is constantly present, which is characterized by ethnic tensions and religious crisis, poverty is on the high side and many Nigerians are economically deprived as a result of pandemic corruption and gross mismanagement of national resources by our political leaders.Nigeria is the most populous black nation on earth with a total population of 150 million citizens as of the 2006 Census and a youth population of 80 million, representing 60% of the total population with a growth rate of 2.6% per year (National Bureau of Statistics-NBS, 2006). It is fortified with various resources—natural, physical, and material—which, if harnessed could lubricate and engineer the nation’s economic growth. Amosun, Sotononde, & Ayodele (2013) and Anayochukwu (2008) rightly noted that the untapped human resources, unfavourable economy and political instability in Nigeria over the years have resulted in a high propensity for criminal behaviour and violence among the youth. For instance, in 2008 Nigerian Tribune reported a ferocious incident of terrorism and radicalization of some young people in one area of Ogun State over the inauguration of a traditional leader.Empirically, Ibrahim (2006)’s survey of children and youth in organized armed violence in Nigeria, showed that disenchantment and frustration of young people due to mass poverty and unemployment has increased the number of aggrieved youths and resulted in the emergence of area boys and Al-majiris who target the very society that alienated them. He concluded that armed militant groups in Nigeria such as Bakassi Boys, Odua Peoples’ Congress (OPC) and Egbesu Boys were made up of youths within 16 - 17 years (40%), 18 – 19 years (10%), 20 - 21 years (20%), and 20 – 23 years (20%). However, violent crime and radicalization among the educated youths (students) has also been on the increase. These incidents of youth crime have created some scenes at local and international levels. The unwelcoming aspect of the episode is that the number of recruits, the density of active crime participants, and the sophistication of operations (Oni, 2008; Obi, 2008; Punch, 2008) create an atmosphere of apprehensiveness among the populace (Alemika & Chukwuma, 2006; Egwakhe & Osabuohien, 2010).One of the techniques that allow people to modify their own behavior is self-management. “Self-management is not a specific, unitary intervention, but rather a collection of techniques. Self-management skills refer to the type of skills taught in competence enhancement programs that help young people manage cognitions, behaviors, and affect. Self-management can be explained by the self-theory, which believes that individuals have potential for self-actualization. Carl Rogers, the proponent of this theory, believed that human beings have inherent tendency to develop their “self” in the process of interpersonal and social experiences, which they have in the environment (Chauman 2000). Since the individual has the potential for self-actualization, self-management techniques will make the rebellious individual take part in the management of his own behavior. Self-management skills can help youth manage cognitions, behaviors, and affect such as decision-making, problem-solving, and coping skills. A latent construct of self-management comprises of indicator measures of decision-making, problem-solving, self-control, and self-reinforcement skills (Griffin, Scheier & Botvin, 2009). Regardless of the specific elements, all self-management techniques are implemented to help people control their own behavior with less reliance on outside behavior-change agents (Harrison, 2005). The self-management procedures consisted of a package of several specific self-management techniques. The body of research focusing on the role of such skills in the development of behavior problems among children and adolescence has been growing in recent years. Several recent studies have examined the protective effects of conceptually related constructs such as self-control, self-regulation, and executive functioning skills in youth development (Adeoye, 2012; Aderanti & Hassan, 2011; Griffin, Scheier & Botvin, 2009).In a study of college undergraduates, poor emotional self-regulation was associated with greater participation in risky behaviors such as smoking, while poor cognitive self-regulation appeared to increase faulty risk assessments and led to an over-emphasis on the benefits of risky behavior (Magar et al., 2008). Self-management therapy has been reported to be effective in stamping out maladaptive behaviour among children and adolescents (Adeoye, 2012, Aderanti, 2006, Griffin, Scheier & Botvin, 2009).Lange & Jakubowski (1976) define assertiveness as standing up for personal rights and expressing thoughts, feelings, and beliefs in direct, honest, and appropriate ways which do not violate another person’s rights. This simply means that an assertive person will always be proactive and not reactive no matter how awful the situation he finds himself. Assertiveness training according to Mehrabi Zade, Taghavi, & Attari (2009) is a structural intervention which is used for social relationship improvement, anxiety disorder therapy, and phobias in children, teenagers and adults alike. Research have shown that assertiveness training is a multi-content method that embraces guidance, role playing, feedback, modeling, practice and the review of trained behaviors (Iro-Idoro, 2013, McCartan & Hargie, 2004). This training over the years have been used as an instrument for initiating and maintaining socially supportive relationships and hence enjoying better emotional well-being (Eskin, 2003). It promotes mental health in adolescence and directly influence individual self-esteem (Bijstra et al., 1994), reduces psychological distress (Taylor et al., 2002), depression (Eskin, 2003), and risk behaviour (Cuijpers, 2002). Demographic variables such as gender have been reported by earlier studies to have significant moderating effect on effectiveness of assertiveness in adolescents. For instance, Eskin (2003) reported that boys are more assertive than girls while Bourke (2002) findings show that girls have a significantly higher score on assertive communication and independence. However, a recent study by Karagözog˘lu, Kahve, Koç, & Adamis¸og˘lu (2008) revealed no significant gender differences in assertiveness.Emotional intelligence has been seen as the capacity of creating positive outcomes in relationships with others and oneself, as well as adequate relationship with the immediate environment which will promote peaceful co-existence among significant others. Mayer & Salovey (1993) sees emotional intelligence as the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions. Previous research have revealed positive correlations between assessed emotional intelligence scores and one's positive perceptions, social interactions, and one’s ability to cope in stressful situations (Bar-On, 2006; Mayer & Salovey, 1997). Therefore, emotional intelligence training is one of the major skills needed by individual especially adolescents for self- control, self-awareness, cooperation and empathy that are necessary for sound decision-making. Smith (2007) asserts that such a skill is critical to making the right choices and in molding the adolescent’s brain for making strong emotional responses to meet daily life challenges. According to Stein, (2009) emotional intelligence creates self-awareness among adolescents, which is the ability to understand one’s emotions and feelings. It enables an individual to tune into and evaluate his or her true feelings. An understanding of one’s true feelings grants an individual the power to manage his or her emotions.Furthermore, Locus of control which is a personality construct refers to an individual’s perception of the locus of events as determined internally by his or her own behaviour versus fate, luck or external circumstances. It is a belief about whether the outcomes of our actions are contingent on what we do (internal control orientation) or on events outside our personal control (external control orientation) (Zimbardo, 1985 cited by Nwakwo, Balogun, Chukwudi, & Ibene, 2012). Also, gender is the moderating variable of the study which was believed to have been having consistent direct and indirect impact on behavioural change (Abosede, 2007; Adeyemo, 1999; Ayodele, 2011; Carless, 2004). Thus, this study believes that making a connection between locus of control and gender and the independent variables will offer insights unlike those provided in the literature to date.While acknowledging the fact that different studies had established the effectiveness of self-management (Adeoye, 2012, Aderanti, 2011, Griffin, Scheier & Botvin, 2009); assertiveness training (Eskin, 2003; Iro-Idoro, 2013, McCartan & Hargie, 2004) and emotional training (Bar-On, 2006; Mayer & Salovey, 1997; Smith, 2007) as training skills needed by individual for self- control, self-awareness, cooperation and empathy that are necessary for sound decision-making and peaceful co-existence; there has been no study till date that combine the three treatment packages in reducing or stamping out potentials for terrorism and violence among the adolescents. Therefore, this study sees the need to look into the differential effectiveness of the therapeutic packages in order to reduce or stamp out the tendency of being violent, radical, and being a terror among our youths who were children of yesterday, adults of today and elders/leaders of tomorrow.

2. Research Hypotheses

- 1. There is no significant difference in the effect of self-management, emotional intelligence and assertiveness training programs on participants’ potentials for terrorism and violence levels.2. There is no significant gender difference in the effect of self-management, emotional intelligence and assertiveness training programs on participants’ potentials for terrorism and violence levels.3. There is no significant locus of control difference in the effect of self-management, emotional intelligence and assertiveness training programs on participants’ potentials for terrorism and violence levels. 4. There is no significant gender difference in the effect of self-management, emotional intelligence and assertiveness training programs on participants’ potentials for terrorism and violence with different locus of control.

3. Methodology

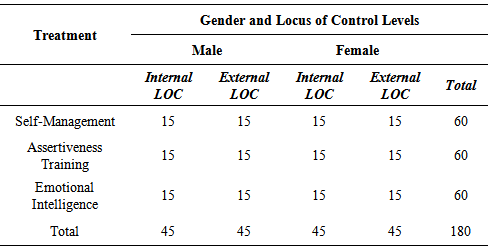

- Research Design: The quasi experimental pretest, control group research design of 3x2x2 factorial matrix type was used for this study. This involved three experimental groups (exposed to treatment), gender (male and female) and locus of control (internal and external).Population, sample and sampling method: The statistical population in this research consisted of all the senior secondary school two (SS2) students. Three coeducational secondary schools were selected through simple random sampling from three different Local Government Areas in Remo educational block of Ogun State, Nigeria. This was done to cater for the three experimental groups needed. In order to determine the statistical sampling, three hundred (300) students were chosen from both genders. Rotter’s locus of control and crime behaviour battery was completed for indicating the locus of control levels and terrorism potentials. From the main sample of 300 students, 180 students were chosen who scored high marks in crime behaviour battery showing high potentials for terrorism, while locus of control scale was used to group the students further into those with internal and external locus of control in their acts. Their age ranged between fourteen (14) and seventeen (17) years with a mean age of 15.7 years. The students were further assigned to the treatment groups as shown in Table 1.

|

4. Results

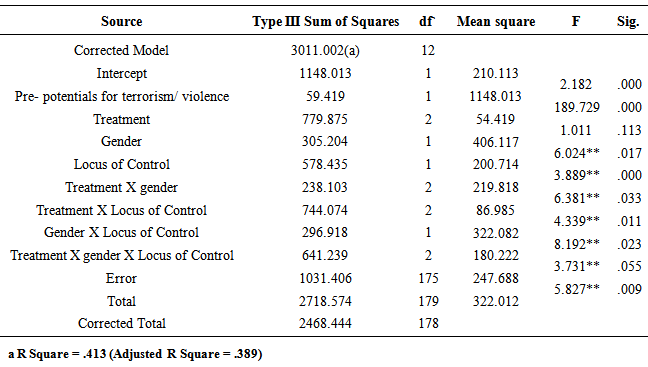

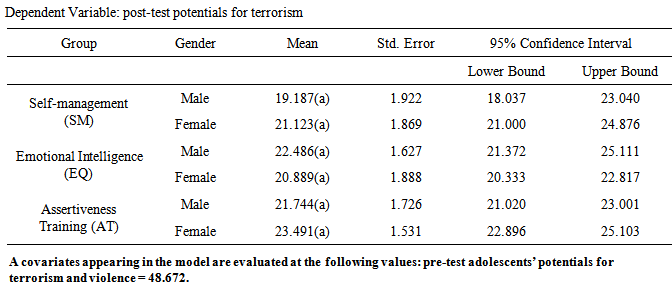

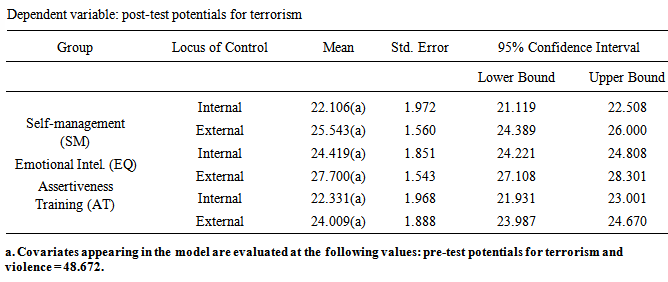

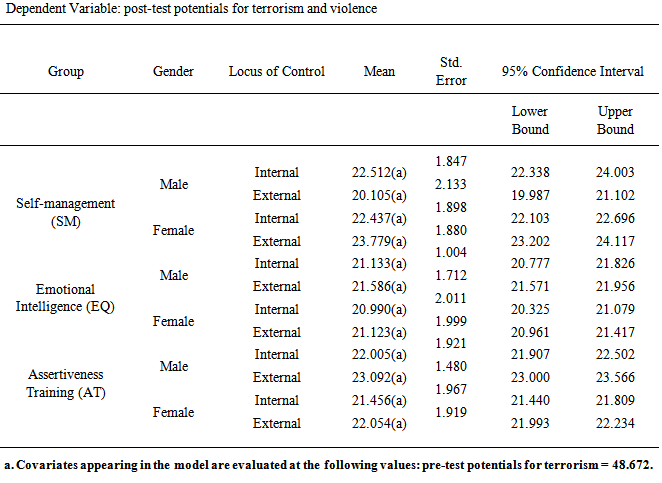

- The outcome of this study indicated a significant effect of treatment on participants’ potential levels of terrorism and violence (F(2.175) = 6.024; p = .000). Also, a significant main effect of gender (F(1.175) = 3.881; p = .000), main effects of locus of control was observed (F(1.175) = 6.381; p = .033) on participants’ potentials for terrorism and violence. The results also revealed a significant two-way interaction effects of treatment and gender (F(1,175) = 4.339; p = .011); gender and locus of control (F(2,175) = 3.731; p = .055). A significant two-way interaction effects of treatment and locus of control was observed (F(1,175) = 8.192; p = .015). The results showed further that a three-way interaction effect of treatment, gender and locus of control (F(2.175) = 5.827; p = .009) on participants’ potentials for terrorism and violence. See Table 2 for details.

|

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion

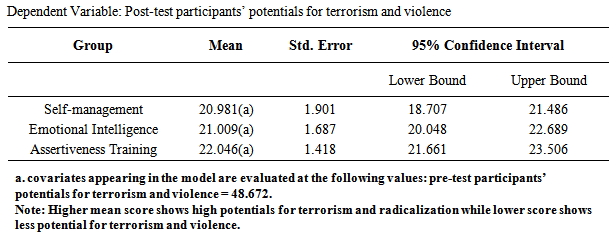

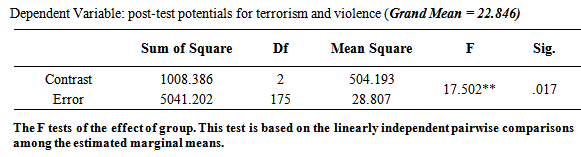

- This study examined the differential effectiveness of the therapeutic packages (self-management, emotional intelligence and assertiveness training programs) and the moderating roles played by gender and locus of control in order to reduce or stamp out the tendency of being a terrorist among Nigerian adolescents. Therefore, the results of the first hypothesis show a significant difference in the effect of self-management, emotional intelligence and assertiveness training programs on participants’ potentials for terrorism and violence levels. The implication of this finding is that the three treatment packages individually are potent in stamping out potentials for terrorism and violence in youths. This might be as a result of participants’ exposure to ten weeks treatment. This indicates not only the effectiveness of the three treatment strategies but also the utilization of treatment gains by the participants as well. The present findings lend good credence to the findings and outcomes of various researchers who exposed their subjects to either self-management, emotional intelligence and assertiveness training programs that have been used successfully in managing behaviour problems such as bullying, communication problems and rebellion (Adeoye, 2012; Aderanti & Hassan 2011; Griffin, Scheier & Botvin, 2009). Another significant finding of this study is the significant difference in the effectiveness of the treatment packages in favour of self-management as shown in Table 3 above (SM = 20.981 and 1.901; EQ = 21.009 and 1.687; AT = 22.046 and 1. 418). This difference could be based on the premise that self-management is not a specific, unitary intervention, but rather a collection of techniques. A significant gender difference was observed in the effect of self-management, emotional intelligence and assertiveness training programs on participants’ potentials for terrorism and violence. The results as recorded in Table 5 revealed gender differences in the mean scores of the effect of the therapeutic packages on participants’ potentials for terrorism and violence, and it was shown that male participants benefit more from self-management and assertiveness training programs while the female benefit more from emotional intelligence training. The results supported the previous findings that gender has been having consistent direct impact on behavioural change (Ayodele, 2011). It should be noted, however, that the gender difference accounted for in this study cannot be explained empirically. This came as a surprise as the previous findings of Abosede (2007), Adeyemo (1999) and Salami (1999) claimed that gender does not consistently have direct impact on outcome variables such as behavioural change.The hypothesis that stated no significant locus of control difference in the effect of self-management, emotional intelligence and assertiveness training programs on participants’ potentials for terrorism and violence levels cannot be sustained in this study. The results as shown in Table 6 revealed LOC differences in the mean scores of the effect of the therapeutic packages on participants’ potentials for terrorism and violence. It was shown that all the therapeutic packages (self-management, emotional intelligence and assertiveness training programs) work more on the individual internal LOC compared to external LOC. It can be deduced that since LOC is a personality construct that reflects individual’s perception of the locus of events as determined internally by his or her own behaviour versus fate, luck or external circumstances, the difference in the findings could be based on the premise that individual behaviour is rooted in factors inherent within (thought and emotions) and outside the individual. This corroborates the findings of Ayodele (2011), Azeez (2007), Baron and Bryne (1997), Zajonc & McIntocsh (1992) that we all experience and express emotions throughout our daily lives, and our emotional thought at any given moments influences our perceptions, cognition, motivation, decision making and interpersonal judgments.The outcome of the fourth hypothesis revealed a significant gender difference in the effect of self-management, emotional intelligence and assertiveness training programs on participants’ potentials for terrorism and violence with different locus of control levels. Therefore, there is a significant difference in the three way interactions of treatment, gender and locus of control in the reduction of potentials for terrorism and violence levels among adolescents. This result is not surprising either since gender and locus of control play an important and well-documented role in behaviour modification among youths (Abosede, 2007; Adeyemo, 1999; Ayodele, 2011; Nwakwo, Balogun, Chukwudi, & Ibene, 2012).

6. Conclusions and Implication of Findings

- This study found the effectiveness of self-management (SM), emotional intelligence (EQ) and assertiveness training (AT) programs in reducing the potentials for terrorism and violence among adolescents in Nigeria. From the findings, it was observed that conflicts within and around us could turn people’s intention from creative production to creative destruction, which could also soiled deep into our personal, social, and political orientation. With the help of the therapeutic packages, youths’ maladaptive behaviour could be properly managed.The findings have shown that the treatment packages could be used as veritable tools in equipping adolescents with necessary skills that could be used to expedite some kinds of cognitive processes such as positive moods, decision-making, problem-solving, self-control, and self-reinforcement skills, therefore, bringing about better future and peaceful co-existence among the people of the world.It is therefore suggested that all stakeholders in the training of youths for better tomorrow especially school counsellors, counselling psychologists should update their knowledge and skills on the use of some of these treatment packages that could help adolescents improve their psychological well-being, enhance relationships, and live a meaningful and fulfilled life. At all levels of education, guidance counsellors could also embark on continuous professional development to ensure that they work with models of best practice in line with their code of professional ethics.

References

| [1] | Adeoye, A.O (2012). Effects of contingency management and cognitive self-instruction on bullying behaviour among secondary school students in Ogun State, Nigeria. A post-field report of the department of educational foundations and counseling, faculty of education, the post-graduate school, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye. |

| [2] | Abosede, S. C. (2007) Effect of mastery learning strategy on the academic achievement of students in business studies. Ogun Journal of Counselling Studies, 1, 1, 17-25. |

| [3] | Aderanti, R.A. (2006). Prevalent of adolescents’ delinquent behavioral patterns: An issue in counseling psychology and implications for national development. A paper presented at the 1st National conference of college of applied education and vocational technology. Tai Solarin University of Education, Ijagun. (unpublished) |

| [4] | Aderanti, R.A. & Hassan, T. (2011). Differential effectiveness of cognitive restructuring and self-management in the treatment of adolescents’ rebelliousness. The Romanian Journal of Psychology, Psychotherapy and Neuroscience, 1(1), 193-217. www.irscpublishing.com. |

| [5] | Adeyemo, D. A. (1999) Career awareness training and self-efficacy intervention technique in enhancing the career interest of female adolescents in male dominated occupations. Nigeria Journal of Applied Psychology, 5, 1, 74-92. |

| [6] | Alemika, E. E. & Chukwuma, I. C. (2006). Criminal victimization and fear of crime in Lagos Metropolis, Nigeria. Cleen Foundation Monograph Series, No. 1. www.africanpolicing.org/reading_list.php. |

| [7] | Anachyochukwu, A. (2008, February 12). On a gunpowder keg. Tell Magazine, p.16. |

| [8] | Animashahun, R.A. (2004). Crime behaviour factor battery. Stevart Graphic Enterprises, Ibadan, Oyo State. |

| [9] | Amosun, O., Sotonade, O. & Ayodele, K. (2013). Socio-cultural determinants of domestic terrorism in Nigeria: the counselling implications. Paper delivered at the Ogun CASSON. |

| [10] | Ayodele, K. O. (2012). Terrorism potentials and radicalization of youths: Internet usage as a mediator. (In press). |

| [11] | Ayodele, K. O. (2011). Fostering adolescents’ interpersonal behaviour: an empirical assessment of enhanced thinking skills and social skills training. Edo Journal of Counselling, 4(1& 2), 62-74.www.ajol.info/index.php/ejc/article/download/72725/61641. |

| [12] | Azeez, R. O. (2007). Intelligence and emotional intelligence as predictors of interpersonal relationship among academic staff of the two state universities in Ogun State. The Counsellor, 23, 84-92. |

| [13] | Baron, R.A., & Byrne, D. (1997). Social psychology, 8th ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. |

| [14] | Bar-On, R. (2006). The bar-on model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI). Psicothema, 18, supl., 13-25. |

| [15] | Bijstra, J.O., Bosma, H.A., & Jackson, S. (1994). The relationship between social skills and psycho-social functioning in early adolescence. Personality and Individual Differences, 16, 767–776.www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0191886994902186. |

| [16] | Bourke, R. (2002). Gender differences in personality among adolescents. Psychology, Evaluation & Gender, 4, 31–41. |

| [17] | Chauham, S.S. (2000) Advanced educational psychology. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House PVT Ltd. |

| [18] | Cuijpers, P. (2002). Effective ingredients of school-based drug prevention programs. A systematic review. Addictive Behaviors, 27, 1009–1023.www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.pubmed/12369469. |

| [19] | Egwakhe, A. J. & Osabuohien, E. S. (2009). Educational backgrounds and youth criminality in Nigeria. InFo, 12(1), 65-79. |

| [20] | Eskin, M. (2003). Self-reported assertiveness in Swedish and Turkish adolescents: A cross-cultural comparison. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 44, 7–12. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.pubmed/12602998. |

| [21] | Griffin, K., Scheier, L. & Botvin, G. (2009). Developmental trajectories of self-management skills and adolescent substance use. Health and Addictions, 9(1), 15-37. www.haaj.org/sites/default/files/developmental_trajectories |

| [22] | Harrison, H. (2005). The three-contingency model of self-management. A Ph. D Dissertation of the Graduate College. |

| [23] | Ibrahim J (2006). Democratic Governance and the Citizenship Question: All Nigerians Are Settlers. Dawodu.com. |

| [24] | Iro-Idoro, C. B. (2013). Assertiveness, emotional intelligence and interpersonal skills training programmes as strategies for enhancing nurses’ work attitude in Ogun State. A post-field report of the department of educational foundations and counseling, faculty of education, the post-graduate school, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye. |

| [25] | Kahana, S., Drotar, D., & Frazier, T. (2008). Meta-analysis of psychological interventions to promote adherence to treatment in pediatric chronic health conditions. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33(6), 590-611.www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.pubmed/18192300. |

| [26] | Karagözog˘lu, S., Kahve, E., Koç, Ö., & Adamis¸og˘lu, D. (2008). Self-esteem and assertiveness of final year Turkish university students.Nurse Education Today, 28,641–649. |

| [27] | Lange, A. J. & Jakubowski, P. (1976). Responsible assertive behavior. Champaign IL: Research Press. |

| [28] | Magar, E. C., Phillips, L. H., & Hosie, J. A. (2008). Self-regulation and risk-taking. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 153-159.www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/SO191886908001037. |

| [29] | Mayer, J. D. & Salovey, P. (1993). The intelligence of emotional intelligence. Intelligence, 17, 433-442. www.unh.edu/emotional_intelligence. |

| [30] | Mayer, J. D. & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? in P. Salovey and D.J. Sluyter (eds.), Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Educational Implications. New York: Basic Books, pp. 3-27. |

| [31] | McCartan, K. & Hargie, O. (2004). Assertiveness and caring: Are they compatible? Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13, 707-713.www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00964.x/pdf. |

| [32] | Mehrabi Zade, M, Taghavi, S., & Attari, Y. (2009). Effect of group assertive training on social anxiety, social skills and academic performance of female students. Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 1, 59-64. |

| [33] | National Bureau of Statistics-NBS, (2006). |

| [34] | Nwankwo, E., Balogun, S., Chukwudi, T., & Ibeme, N. (2012). Self-esteem and locus of control as correlates of adolescents well-functioning. British Journal of Arts and Social Sciences, 9(2,) 214-228. www.bjournal.co.uk/paper/BJASS_9_2/BJASS_09_02_09.pdf. |

| [35] | Obi, D. (2008, April 8). Nigeria’s poor image: Students are equally guilty panelists. Business Day, p. 4. |

| [36] | Ogundiya, S. & Amzat, J. (2008). Nigeria and the threats of terrorism: myth or reality. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 10(2), 165-189. |

| [37] | Oni, A. (2008, April 2). Robbers snatch bullion van, kill two in Sagamu. The Punch, p. 5. |

| [38] | Salami, S.O. 1999. Generalized Self-Efficacy Questionnaire. Ibadan: Department of Guidance and Counselling, University of Ibadan, Ibadan. |

| [39] | Sarkova1, M., Bacikova-Sleskova1, M., Orosova, O., Geckova, A., Katreniakova, Z., Klein, D., Heuvel, W., van Dijk, J. (2013). Associations between assertiveness, psychological well-being, and self-esteem in adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43, 147–154. www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00988x/pdf |

| [40] | Smith, H. (2007). Teaching adolescents: Educational psychology as a science of signs. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. |

| [41] | Stein, S. (2009). Emotional intelligence for dummies. New York, NY:John Wiley & Sons. |

| [42] | Tatar, M., Amram, S., & Kelman, T. (2011). Help-seeking behaviours of adolescents in relation to terrorist attacks: The perceptions of Israeli parents. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 39(2), 131-147.www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/recordDetail?accno=EJ915938. |

| [43] | Taylor, C.A., Liang, B., Tracy, A.J., Williams, L.M., & Seigle, P. (2002). Gender differences in middle school adjustment, physical fighting, and social skills: evaluation of a social competency program. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 23, 259–272.www.open-circle.org/files/oc_middle_school_study.pdf. |

| [44] | The Punch. (2008, April 13). The state of Nigerian Universities, p. 14. |

| [45] | Wysocki, T. (2006). Behavioral assessment and intervention in pediatric diabetes. Behavior Modification, 30(1), 72-92. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pudmed/16330520. |

| [46] | Zajonc, R. B., & McIntosh, D. N. (1992). Emotions research: Some promising questions and some questionable promises. Psychological Science, 3,70-74. |

| [47] | Zimbardo, P. G. (1985). Psychology and life. Boston: Ally & Bacon. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML