-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2014; 4(5): 196-207

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20140405.04

Measuring the Influence of Self-Efficacy, Fear of Stigma, Prior Counseling Experience, on College Students’ Attitudes toward Psychological Counseling

Fatima Abdalraheem Al-Nawayseh

College of Science and Art, Qaseem University, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Fatima Abdalraheem Al-Nawayseh, College of Science and Art, Qaseem University, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The purpose of this research study was to measure the influence that self-efficacy, fear of stigma, and had on college students’ attitudes toward counseling. A sample of (178) undergraduate college students from Mu,tah university in Jordan participated in this survey research. Participant data were examined separately for students with prior counseling experience and no prior counseling experience. One-way ANOVAs were calculated to investigate whether differences existed between these two groups in their ratings of self-efficacy, stigma and attitude toward counseling. The results showed the group that had no prior counseling reported more concerns of being stigmatized by counseling, rated themselves as more encourage individuals, and had lower perceptions of self-efficacy than the group with prior counseling experience. These results suggest that students who have not experienced counseling are a varied group, ranging from very encouraged individuals to those doubting their own capabilities Pearson Product-Moment correlation coefficients were calculated to investigate the relationships between stigma, self-efficacy and attitude toward counseling for student participants. Results indicate that more positive attitudes toward counseling were positively related female. These analyses also revealed that self-efficacy was associated with being male and with higher levels of encouragement. Two multiple regressions (i.e., group that had prior counseling experience and group than had not had prior counseling experience) were calculated to investigate which of the variables listed above were the best predictors of participants’ attitudes toward counseling. Among participants who had no prior counseling experience, self-efficacy, and gender were significant predictors of attitude toward counseling. Among participants who had prior counseling experience, gender and age were the significant predictors of attitude toward counseling. An ANCOVA revealed that the majority of the variance in attitudes toward counseling was accounted for by prior counseling experience. Findings suggest that, although the fear of being stigmatized may not affect students' attitudes toward counseling, it remains an important variable in the decision to seek or not seek counseling services. Actually engaging students in counseling-related experiences will have the greatest influence on positively shaping their attitudes toward counseling.

Keywords: Counseling, Attitude, College Student, Self-Efficacy, Stigma, Prior Counseling Experience

Cite this paper: Fatima Abdalraheem Al-Nawayseh, Measuring the Influence of Self-Efficacy, Fear of Stigma, Prior Counseling Experience, on College Students’ Attitudes toward Psychological Counseling, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 4 No. 5, 2014, pp. 196-207. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20140405.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Students can feel overwhelmed or discouraged as they face the various life and academic tasks that confront them in today’s complex university. In an effort to support students’ efforts to cope with the challenges they face. Supporting students through their academic programs and promoting their development are central functions in meeting the stated mission of any university. Students' attitudes toward the use of counseling services are influenced by multiple factors, one of which is stigmatization. The negative stigma attached to mental illness and the consequent belief by some people that those who seek counseling are diminished in some way have been problematic and continue to concern (Esters, Cooker, & Ittenbach, 1998). There are both the stigma attached to the presenting concern, such as rape or incest (Amato & Saunders, 1985; Ogletree, 1993) and the stigma attached to needing help for psychological concerns that negatively affect students' attitudes toward seeking professional help. Prior experience with the use of counseling services, as in the case of relatives or friends, has been shown to have a positive influence on one’s attitude toward counseling (Komiya & Eells, 2001). Sometimes even prior positive experience does not always relieve students’ concerns about being stigmatized. Instead, students are often left still feeling anxious about what family, friends, and acquaintances will think of their seeking counseling (Halgin, Weaver, & Donaldson, 1986).The researchers have found that negative help-seeking attitudes are actually associated with lower levels of self-efficacy (Garland & Zigler, 1994) and a general lack of self-effectiveness. Believing in one's own personal capabilities seems to play an important role in the decision to seek counseling. Moreover, because counseling relies upon the building of a trusting relationship, establishing such a relationship with a trained helping professional can be extremely challenging for these students. Such students question their own resourcefulness and the ability of others to be helpful. Further, they lack a sense of connectedness to the larger community and are less likely to try new experiences. Statement of the Problem Untreated, psychological disorders pose a risk to students as well as to the larger university community. In particular, college students face potential and compounding negative consequences from untreated psychological disorders such as (a) an inability to attend classes regularly, (b) reduced academic performance, (c) premature withdrawal from the university, and (d) dismissals due to conduct problems. The most serious consequence of failing to treat psychological disorders is loss of life, either at their own hand or by the actions of others. Significantly, the suicide rates on college campuses have been increasing for the past four decades, with the annual rate of suicide (Meilman, Hacker, & Kraus-Zeilmann, 1993). Violent behavior, which is often linked to alcohol and other drug use and abuse is on the rise on campuses as well (Humphrey, Kitchens, & Patrick, 2000). Student deaths that are listed as accidental (e. g., vehicular crashes) or as arising from medical complications may also be connected to untreated psychological disorders.The risk to students when psychological concerns go untreated is great and efforts are needed to prevent unnecessary suffering. As noted, however, the provision of services is a necessary but insufficient first step in addressing the mental health concerns of University students. To be successful, college student support services personnel must also find ways to engage students’ participation in the use of these services when and as needed. Overcoming their concerns about being stigmatized, raising their levels of self-efficacy, providing positive personal experiences with counseling personnel, and addressing low levels of encouragement are likely to be central counseling strategies for improving the utilization of counseling services on university campuses.Although there is now a comprehensive picture of the factors that influence help-seeking behavior, the problems that arise when psychological disorders go untreated are still increasing. It is imperative that student service personnel address themselves to improving the utilization of counseling services in order to reduce the negative consequences to the individual student and the larger community that are created when psychological disorders go untreated.

1.1. Purpose of the Study

- The purpose of the present study was to examine a set of factors that have been shown to influence the attitudes of college students toward the utilization of counseling services. Specifically, this study explored the relationship between (a) prior personal experience with counseling, (b) level of self-efficacy, (c) concerns about stigmatization, (d) a set of demographic variables and their relationship to students’ attitudes toward counseling. The present study was intended to answer this call by exploring a set of counseling factors that have been shown to influence students' attitudes toward the use of. This research was addressed to close the gap between the offering of services and connecting students to the use of these services.

1.2. Research Questions

- The present study investigated the following research questions:Research Question 1: Are there differences between college students who have had priorcounseling experience and college students who have not had prior counseling experience in their self-ratings of stigma, self-efficacy and attitude toward counseling?Research Question 2: Assuming that there is a main effect of prior counseling for stigma, self-efficacy and attitude toward counseling, what are the direction and strengths of the relationships between gender, age, stigma, self-efficacy and attitude toward counseling for students who have and have not previously received counseling services?Research Question 3: Which of four potential predictor variables (stigma, selfefficacy, gender, and age) contribute significantly to predicting attitude toward counseling?

1.3. Definition of Terms

- 1. Stigmatization: negative judgment by others.2.Self-Efficacy: self-perception of performance capabilities. (Adler, 1931/1980, p. 8).3. Help-seeking: recognizing a difficulty affecting current functioning and making contact with persons who might be helpful in correcting the difficulty.

1.4. Delimitations

- The present study was delimited to college students as the sample for the purpose of specifically exploring college students' attitudes toward counselling.

1.5. Limitations

- Any interpretation of the results of the present study was anticipated to be limited by the following conditions1. The Stigma Concerns subscale of the Thoughts About Psychotherapy Survey (Kushner & Sher, 1991).2. The outcomes of the present study may have been influenced by the fact that participation in the study was voluntary. In particular, student volunteers may share characteristics that contribute to help-seeking behavior, especially for psychological concerns Similarly, students who declined to participate may share characteristics that are negatively related to their attitudes toward counseling. To what extent such characteristics may have influenced the outcomes of the present remains unknown.3. The present study used a convenience sample of college students from mu, ta university and results may not be generalizable to other college student populations.

1.6. Literature Review

- Each new wave of students arrives upon this shore of their new lives as college students, they are provoked to ask themselves "Who am I?" "What do I want?" and "How do I fit in?" Anxiety about themselves and the future that lies before them can arise from what they have yet to discover about themselves and this new and changing world that surrounds them (Von Steen, 2000). In going to college, many students move away from ho familiar support systems only to find themselves facing the challenge of developing new social networks in a university environment and the intellectual rigors of a university curriculum (Sher, Wood, & Gotham, 1996). College students must also learn to deal traumatic life events a psychological problems away from the social network that had supported them until now (Stone & Archer, 1990). While at college, they are neither invulnerable to the problems that confront them college nor insulated from the problems at home. Although, they enjoy academic success and new relationships, and may experience some personal growth and development, there are likely still to be tragedies, failures, family difficulties, and failed intimate relationships with which to contend (Meilman, Hacker, & Kraus-Zeilmann, 1993). It is reasonable to expect that these changes coexist with various forms of distress that reveal themselves as psychological behavioral, and psychosomatic symptoms.Among student affairs professionals, there is a debate, currently, whether today's students have more severe psychological problems than seen in previous decades. This debate has been fueled by several high profile student tragedies that have raised concerns about the status of student mental health (O'Connor, 2001). In increasing numbers, university students report depression, substance abuse, eating disorders, learning disabilities, and adjustment concerns. The number of students seeking services in counseling centers is also rising compared to previous years (O'Connor, 2001).Clearly, today's college students are experiencing significant distress in increasing numbers and evidence clinical symptoms that should be addressed by counseling professionals. Despite the apparent need, however, getting college students to seek appropriate and available services presents yet another challenge to college counseling center.

1.7. Self-Efficacy

- When faced with difficult situation, individuals will try harder and persist longer. Indeed, they may ascribe failures on hard or complex tasks to inadequate efforts on their parts. Ability and past performance have consistently been found to be positively related to self-efficacy (Bandura, 1986; Locke & Latham1990) Several factors appear to contribute to the findings that those who need help mostare less likely to seek it. When individuals repeatedly are unsuccessful, researchers have found that they are likely to attribute the result to low ability. In turn, unwavering low ability attributions can lead to anticipating future failure. Further, low ability attributions may coexist with negative emotions such as melancholy, guiltiness, embarrassment, despair, and resignation and possibly feelings of helplessness, if low ability attributions are global (Abramson, Seligman & Teasdale, 1978). For individuals who combine low expectations with negative emotions, particularly helplessness, receiving help may be considered irrelevant to achievement, with the consequence that they are unlikely to seek help.In addition, help seeking can be especially threatening to these individuals because persistent failure after having sought help might create even more evidence of their assumed low ability and their lower self-worth. Help-seeking may also be viewed by some as dependent behavior and, therefore, be perceived as a threat to one's sense of competence and autonomy or as a barrier to becoming independent (Nelson-LeGall, 1991).

1.8. Fears and Concerns

- Kushner and Sher (1991) reviewed the empirical literature that examined fears and concerns about seeking and utilizing mental health services. They found the following six potential fears related to treatment: (a) fear of embarrassment; (b) fear of change; (c) fears involving treatment stereotypes; (d) fears associated with past experience with mental health service systems; (e) fear of treatment associated with specific phobias; and, (f) fear of being stigmatized (negative judgments). Saunders, Resnick, Holberman, & Blum (1994) found that adolescents who had high suicidal ideation were less likely to seek help than those students who had less severe or no suicidal ideation. As they explained, students appear less likely to seek help as thoughts about suicide increase, a result that points again to the discrepancy between increased need leading to increased help-seeking. Although high suicidal ideation has the element of hopelessness, students also perceived it as stigmatizing and embarrassing.

1.9. Stigma

- Many relevant factors exist that play a role in a person’s decision to seek psychological health services. However, the most frequently cited reason for why people do not seek counseling and other psychological health services is the stigma associated with psychological illness and seeking treatment (Corrigan, 2004). The “stigma associated with seeking psychological health services is the perception that a person who seeks psychological treatment is undesirable or socially unacceptable” (Vogel, Wade, & Haake, 2006, p. 325). Stigma has consistently been cited as one of the main factors inhibiting individuals from seeking mental health care and there is a great deal of research suggestive of the strong stigma attached to psychological illness and seeking psychological services (Brown & Bradley, 2002; Gonzalez, Tinsley, & Kreuder, 2002; Sadow, Ryder, & Webster, 2002; Vogel et al, 2006). This stigma is characterized by fear, mistrust, dislike, and occasionally violence against the mentally ill (Gonzalez et al., 2002) and this stigmatization is pervasive and prevalent in individuals of all ages (Sadow et al., 2002). Stigma is directed toward individuals with psychological health concerns and toward mental health services. In 1999 Surgeon General’s report on mental health (Satcher, 1999, p. 215), stating that the “fear of stigmatization deters individuals from (a) acknowledging their illness, (b) seeking help, and (c) remaining in treatment, thus creating unnecessary suffering” (p. 117). Numerous individuals who could benefit from utilizing some form of mental health service never reach out for help due to the overwhelming prevalence of stigma toward mental illness and mental healthcare. Understanding psychological health care stigma and learning techniques to overcome this barrier is therefore an important priority for professionals and prospective clients alike.

1.10. Attitudes toward Counseling

- In a study by Kushner and Sher (1991), concerns about being stigmatized and the level of psychological distress accounted for 32% of the variance in help-seeking attitudes for females and for persons over 20 years of age. Similarly, fear of coercion and concerns related to the image of those seeking mental health services have been found to negatively influence help-seeking attitudes for males under 20 years of age. Fears and concerns about the nature of mental health services have been shown to negatively influence attitudes toward counseling. Satcher (2000) outlined the following specific suggestions for overcoming stigmatization and discrimination related to using mental health services: (a) increase public awareness of effective treatments; (b) tailor treatments to age, gender, race, and culture; (c) facilitate entry into treatment; and, (d) reduce the financial barriers to treatment. Because of the attention paid to these issues by university personnel, the stigmatization of seeking mental health assistance would be expected to be experienced less by young adults and students on college campuses than the general population.In support of this expectation, researchers were able to measurably reduce stigmatization in a rural adolescent population through mental illness educational efforts. Furthermore, college students are utilizing psychological services more now than in years past (O'Connor, 2001), suggesting that today's college students may be less affected by the fear of being stigmatized. Cramer (1999) found that attitude toward counseling was the most important help-seeking antecedent, even more important than a student’s level of distress. Thus, it can be expected that students experiencing distress will not necessarily seek out psychological help if they have a negative attitude toward counseling. Alternatively, when experiencing a psychological crisis, positive attitudes about help-seeking could lead students to seek mental health services. A robust finding of Cramer's research was that favorable attitudes toward psychotherapy significantly predicted greater perceived likelihood of seeking help regardless of the reasons for which help would have been sought. Thus, keeping in mind that psychological treatment can potentially reduce many of the negative effects associated with mental psychological problems (Kushner & Sher, 1991), it becomes important to know more about the factors that shape people's attitudes toward psychotherapy. Such knowledge could facilitate the development of preventive interventions aimed at increasing favorable attitudes toward counseling. In turn, improved attitudes are likely to promote early use of services rather than during advanced stages of mental disorders (Cepeda-Benito & Short, 1998).

1.11. Conclusions

- College students have shown increasing rates and higher levels of pathology. In response, mental health professionals university campuses have shifted their focus from addressing the informational and educational needs of students to attending to more serious emotional and behavioral problems (Heppner, Kivlighan, Good, Roehlke, Hills, & Ashby, 1994 Research suggests that prior contact with the disciplines of counseling or psychology or with mental health practitioners, or with mental health facilities may reduce a person's treatment fears and promote favorable attitudes toward seeking mental health treatment (Fischer & Farina, 1995). Understanding the differences between students who have and have not had prior personal experience with counseling or psychological services may facilitate the development of interventions to promote the early use of these services rather than during the advanced stages of mental disorders. Based on a review of the literature on help-seeking behavior, stigmatization, prior experience with counseling and self-efficacy appear to be significant contributors to the help-seeking process.

2. Methodology

- The methods and procedures used to assess the relationship between help-seeking behavior, stigmatization, prior experience with counseling, and self- efficacy as variables in the help-seeking process by college students are described.

2.1. Research Questions

- Research Question 1: What differences are there, if any, between college students who have had prior counseling experience and college students who have not had prior counseling experience in their self-ratings of stigma, self-efficacy and attitude toward counseling?Research Question 2: Assuming that there is a main effect of prior counseling for stigma, self-efficacy and attitude toward counseling what are the directions and strengths of relationships between gender, age, stigma, self- efficacy and attitude toward counseling for students who have and have not previously received counseling services?Research Question 3: Which, if any, of the five predictor variables (i.e., stigma, self efficacy, age, and gender) contribute significantly to the prediction of attitude toward counseling for people who have and have not previously received counseling services?Do the regression models that result from subsets of the predictor variables reliably predict attitudes toward counseling for students who have and have not previously received counseling services?

2.2. Sample Size

- An overall sample size of 178 was considered to be sufficient to examine each of the research questions posed.

2.3. Instrumentation

- Previous research had shown that one’s attitude toward counseling, degree of fear of stigmatization, levels of and self-efficacy, and prior counselling experience, along with selected demographic variables, such as gender of age, were significant factors associated with whether or not college students would seek professional counseling help when needed. Instruments selected to measure the sevariables as part of the present study included the following: (a) Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale - Shortened Version (Fisher & Farina, 1995). (b) Stigma Concerns subscale of The Thoughts About Psychotherapy Survey (Deane & Chamberlain, 1994; Kushner & Sher, 1989). (c) The General Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale Revised (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995). (d) questions regarding prior counseling experience and demographics. Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale - Shortened Version (ATSPPH-S). The ATSPPH-S (Fischer & Farina, 1995) is a ten-item instrument used to assess attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. This instrument was selected for its brevity and common usage in the help-seeking literature. It is based on a 29-itemversion previously developed by Fischer and Turner (1970). Each item is rated on a 4-point, Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (“disagree”) to 4 (“agree”) with half of the items. The test-retest reliability of the ATSPPH-S over a 4-week period was .80 and the coefficient alpha was .84, which was replicated in this current study. Support for the construct validity of the instrument was obtained through examination of the pointbiserial correlations between the respondents who had sought help and those who had not. The correlations were .24 (p < .03) for females, .49 (p < .0001) for males, and .39 (p< .0001) overall. The normative sample was comprised primarily of freshmen (74%) with a modal age of 18 years, and 55% of the sample was female (Fischer & Farina, 1995). Stigma Concerns Subscale of The Thoughts About Psychotherapy Survey (TAPS) The TAPS (Deane & Chamberlain, 1994; Kushner & Sher, 1989) (TAPS) uses 30 items to assess fear of psychological services along with therapist responsiveness, and image, coercion, and stigmatization concerns. Respondents indicate their level of agreement to statements using a 5-point Likert scale from 5 (“very concerned”) to 1 (“no concern”). The TAPS has four subscales: Therapist Responsiveness, Image Concerns, Coercion Concerns, and Stigma Concerns.The General Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale – Revised (GPSE-R). The GPSE-R (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995) uses 10 items to assess participants' self-report of self-efficacy. This instrument was selected because it is a brief measurement tool of general self-efficacy. This scale was originally developed in German with 20 items and then reduced to a 10-item version by the same authors (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995). The English version of this scale was used in the present study Respondents indicate their level of agreement to statements using a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“not at all true”) to 4 (“exactly true”), with a score ranging from 10 to 40. Higher scores represent higher levels of self-efficacy.The General Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale - Revised has yielded internal consistencies ranging from .75 to .91 (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995). The Cronbach’s alpha was .80 for this study. Self-efficacy as measured by this instrument has been found correlate positively with self-esteem and optimism and correlate negatively with anxiety, depression, and physical symptoms showing good convergent and discriminant validity (Schwarzer, 1992; Schwarzer & Born, 1997; Schwarzer, Mueller, & Greenglass, 1999).

2.4. Demographic and Previous Counseling Variables

- The demographic information collected from participants included gender, age, and academic classification. Evidence of prior counseling experience was solicited with the question "Have you previously (or currently) seen a counselor, psychologist, or psychiatrist?

2.5. Data Collection

- The researcher collected the data during summer of 2014 in classrooms and organizational meetings at the University using the same approach to collect data at all settings and offering the same incentives to all participants. At times decided on by the classroom instructor or student organization leader, the researcher attended the academic classes and organizational meetings and was introduced by the class instructor or organizational leader as the principal researcher on a study of college students’ attitudes toward counseling. The researcher addressed the students at the beginning of the class time or meeting. Research packets were distributed to all students. A brief introduction was given about the survey and contents of the survey packets (i.e., consent form, survey drawing entry card). Students who were 18 years of age and older were invited to participate in the research study.

2.6. Data Analysis

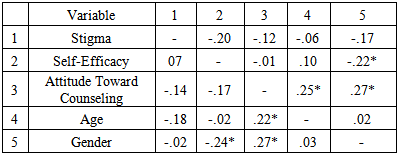

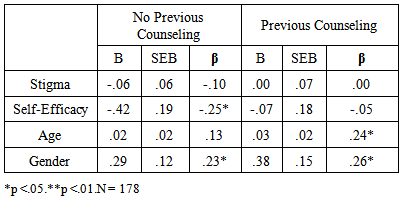

- Data were coded and transferred by the principal investigator from the completed questionnaires to computer data files. The individual research questions and statistical analysis for each question are offered below.Research Question 1What differences, if any, are there between college students who have had prior counseling experience and college students who have not had prior counseling experience in their self-ratings of stigma, self-efficacy and attitude toward counseling?Statistical Analysis: A one-way ANOVA has one predictor variable and one criterion variable. The predictor variable, prior counseling experience, was analyzed with each criterion variable, stigma, self-efficacy and attitude toward counseling.Research Question 2Assuming that there is a main effect of prior counseling on stigma, self-efficacy and attitude toward counseling, what are the direction and strengths of the relationships between gender, age, stigma, self-efficacy, and attitude toward counseling for people who have and have not previously received counseling services? Statistical Analysis: A set of Pearson product-moment correlations was conducted to measure the relationship between gender, age, stigma, self-efficacy and attitude toward counseling for participants who have and have not previously received counseling services.Research Question 3Which of the five predictor variables (stigma, self-efficacy, age and gender) contribute significantly to the prediction of attitude toward counseling for people who have and have not previously received counseling services?Statistical Analysis: Two simultaneous multiple regression analyses were conducted to answer this question. Attitude toward counseling was regressed onto stigma, self-efficacy, age, and gender simultaneously for people who have and have not previously received counseling services.

3. Result

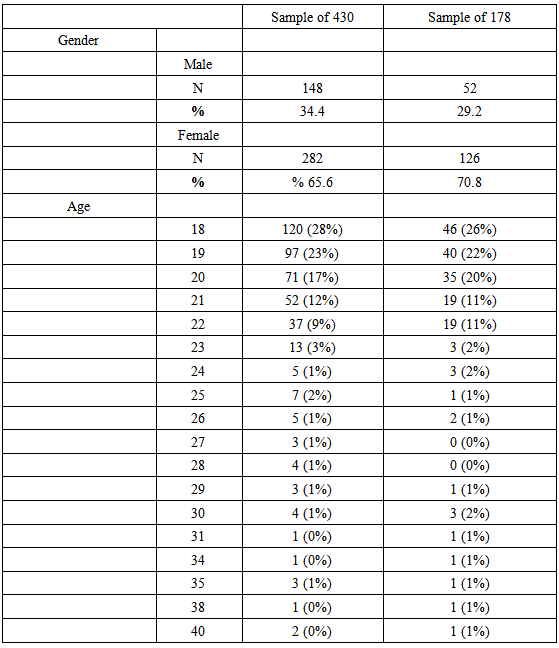

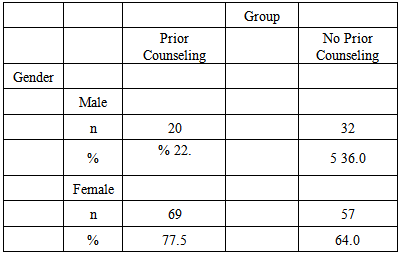

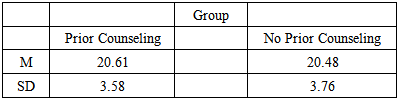

- The current study was designed to obtain a deeper understanding of college students’ attitudes toward counseling with respect to whether or not they would seek counseling services. Analyses were conducted to reveal which of a set of variables known to influence a person's help seeking behavior would be positively related to one's attitude toward counseling. The mean age in the sample was 20.4 years. Of the participants who completed the questionnaire. To control for prior counseling as a variable that was expected to be related to the primary criterion (attitudes toward Counseling, participants who did not report receiving counseling services in the past were randomly selected using an Excel randomization function. the data from (178) participants were used in the analysis, where (89) participants reported that they had received counseling services at some point in the past, and (89) did not.As the data in Table 1 indicate, the samples were more similar than different from each other with regard to gender and age. However, there was a large sampling of younger female participants, with approximately half the sample 18- to 19- year olds and 70% of the sample consisting of female participants. As noted earlier in this chapter, the data for the sample of 178 participants was grouped into "received prior counseling" and did not receive prior counseling.” Gender and age differences were examined for each of the two groups. Gender The gender of the groups (prior and no prior counseling) was fairly skewed, with more female representation in the group that had prior counseling. Specifically, females comprised 77.5% of the prior counseling group. There was no statistically significant difference (p>.05; X2 = 3.93) between the groups in reference to gender. Table.2 depicts the gender distribution of the sample.

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Summary

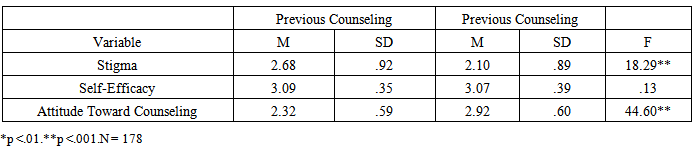

- Given the present concerns about the psychological health of today's college students, there has been a call to understand better how to meet the psychological needs of today’s college students (Bishop, Bauer, & Becker, 1998). The purpose of the present study was to examine a set of factors that have been shown to influence the attitudes of college students toward the utilization of counseling services.Specifically, the present study explored the relationship between (a) prior personal experience with counseling, (b) level of self-efficacy, (c) concerns about stigmatization and (d) a set of demographic variables and the relationship between thesevariables and students' attitudes toward counseling. The purpose of the study was to understand college student’s attitudes toward counseling more fully. Specifically, the study compared self-reported differences in stigma fears, level of self-efficacy, and attitude toward counseling for students who had and had not had prior counseling experience.The research questions that guided the present study were: (a) what, if any, differences are there between college students who have had prior counseling experience and college students who have not had prior counseling experience in their self-ratings of stigma, self-efficacy, encouragement, and attitude toward counseling?; (b) Assuming that there is a main effect of prior counseling for stigma, self-efficacy, encouragement, and attitude toward counseling, what are the direction and strengths of the relationships between gender, age, stigma, self-efficacy, encouragement and attitude toward counseling for students who have and have previously received counseling services?; and (c) Which of the fourth predictor variables (i.e., stigma, self-efficacy,age and gender) contribute significantly to the prediction of attitude toward counseling for students who have and have not previously received counseling services? Do the regression models, resulting from subsets of the five predictor variables, reliably predict attitudes toward counseling for students who have and have not previously received counseling services. The present study reviewed an analysis of data collected from 178 undergraduate students attending a four-year university in Jordan. There were statistically significant differences (p<.05) concerning fear of stigma, and attitude toward counseling between the groups that had received prior counseling and had not received prior counseling. However, there were no statistically significant differences (p<.05) for perceived self-efficacy for these two groups of college students. Students who had prior counseling experience had less fear of stigmatization, perceived themselves as more positive attitudes toward counseling. Models of predicting attitudes toward counseling were tested with statistically significant findings (p<.05). College student age and gender accounted for 15% of the variance among participants who had previously received counseling (R2 = .15, F(5, 83) = 2.95, p <.02). Specifically, being older rather than younger, and female rather than male, predicted those students who had more positive attitudes toward counseling among those students who had prior counseling experience.The prediction model for those students who had not received counseling explained 21% of the variance in attitude toward counseling (R2 = .21, F(5, 83) = 4.41, p <.01). The college students who perceived themselves as more encouraged, less self-efficacious, and who were male had less positive attitudes toward counseling among those students who had not had prior counseling experience. Lastly, the contribution of prior counseling experience to the variance in college student attitude toward counseling was examined. The significant contributing variables that explain the variance in college student attitude toward counseling was, gender, age, and prior counseling experience. The majority of the variance in attitudes was explained by prior counseling experience F(1, 171) = 41.16, p <.001, 2 =.19.

5. Conclusions

- Findings from Research Question 1 Regarding Measured Differences in Attitudes Counseling. In the first analyses (ANOVA), the data were grouped by student participants who have and have not had counseling experience and differences in stigma, self-efficacy, and attitudes toward counseling were examined Toward From these analyses, it was discovered that college students who did not have counseling experience rated themselves as more fearful of the stigma related to counseling, and had more negative attitudes toward counseling than students who had participated in counseling. Students with negative attitudes toward counseling and who fear being stigmatized for seeking counseling services may not view counseling as a viable option for addressing problems or concerns, a conclusion supported by other studies (Fischer & Farina, 1995; Connor, 2001; Cramer, 1999).Students with stigma concerns who have not experienced counseling are apprehensive about how others may view them if they seek counseling services. Reducing the stigma of counseling and mental health issues has been attempted through psycho-educational interventions with adolescents and college students (Esters, Cooker, &Ittenbach, 1998; Gonzalez, Tinsley, & Kreuder, 2002) with varying degrees of success.The interventions by Esters, et al., (1998) were several hours in length by contrast to those by Gonzalez et al., (2002) interventions, which were about fifteen minutes in length. Comparing the results of these two studies, it appears that a longer intervention can have a more lasting effect on changing attitudes toward counseling and perceptions of mental illness. Although college counselors may not often have two hours to spend specifically on changing students' attitudes and perceptions, there are other means to address these issues, such as utilizing counseling center websites. Information and online screenings can be offered to students that may reduce their fears associated with counseling and mental illness. Students can spend the time necessary to understand their current symptoms and find information on both self-help and professional treatment for their concerns by completing confidential online screenings and privately exploring mental health information on-line. The marketing of web resources could direct students to these services. As a consequence, students who would not be expected to browse the counseling center website or other mental health websites on campus for fear of discovery or other potentially negative consequences, might be encouraged to explore non-university sites anonymously.Findings from Research Question 2 Regarding Relationships between Variables Results of the correlations between the variables, stigma, self efficacy, attitude toward counseling, age, and gender were very similar for both participant groups (received counseling and have not received counseling). More positive attitudes toward counseling were associated with being female and self efficacy was positively related to being male. These findings and the failure to find differences between the two counseling groups could be due to the lack of variability in the participants.Forty-eight percent of the sample (86 of 178 participants) were 18- to 19-years of age and 70.8 % of the sample (126 of 178 participants) were Female participants in the present study expressed more positive attitudes toward counseling whether or not they had prior counseling experience. It appears that having a positive attitude toward counseling is not dependent on prior experiences with counseling and nor does having experience with counseling negatively influence their attitudes toward counseling.Male participants, by comparison, held more negative attitudes toward counseling, which may have discouraged them from seeking counseling. Without having had counseling experiences, their negative attitudes apparently remain unchanged, if not also unchallenged by a positive and corrective experience. Findings from Research Question 3 Regarding Predicting Attitude Toward Counseling in the College Student Population Separate prediction models were considered for the no prior counseling experience and the prior counseling experience groups. Of the variables examined in the present study, only gender and age predicted attitude toward counseling for students who had counseling experience Being an older female accounted for only 15% of the variance in attitude toward counseling for this group, leaving 85% of the variance still unexplained. Although these findings are supported by earlier studies, they do not add anything to predicting the attitude toward counseling of a student who has prior counseling experience. Critically, the age at which students in this study had prior counseling experience and the nature of that experience are unknown. Based on the findings, it is possible to speculate that a process of maturation, or the accumulation of relevant life experiences other than counseling, enables students to entertain a wider range of problem-solving choices, which may include counseling.Alternatively, female socialization includes the expectation that they must rely upon others for help or that they will need others to “fix” conditions that are beyond their own control. How gender socialization, problem awareness, and help seeking are related to the development of attitudes toward seeking counseling services remains unclear. Exploring attitudes toward counseling for students with prior counseling experience may better be accomplished through qualitative approaches that could assess the prior counseling experience of both males and females from their unique perspectives.In particular, how males and females develop attitudes toward counseling and how these attitudes are related to any subsequent experience with counseling are critical questions to be answered by further research. Self-efficacy, and gender explained 21% of the variance in attitudes toward counseling for students who have not had prior counseling experience. Male students with no counseling experience who perceived themselves as less efficacious and more encouraged held more negative attitudes toward counseling.Help-seeking may also be viewed by students with low self-efficacy as dependent behavior and, therefore, constitute a threat to one's sense of competence and autonomy or provide a barrier to becoming independent (Nelson- LeGall, 1981). For student retention purposes, it may be useful to identify less efficacious students through the use of selected performance indicators (e.g., failing grades, missing multiple classes, lack of participation) and by being more proactive as student services professionals in assisting students to become more efficacious.Students with low self efficacy may need not only to be made more aware of available counseling services, but may also need to be instructed more specifically about the personal and academic conditions under which they may find counseling to be useful. Deliberate instruction may be particularly important for male students who may only have mandated counseling experiences as a consequence of alcohol or other drug violations or other conduct infractions. These counseling experiences may only serve to reinforce student beliefs that someone other than themselves will tell them when and under what conditions counseling can be useful. Students' fear of being stigmatized by attending counseling was not a predictor of attitudes toward counseling for students who neither have nor have not had prior counseling experience.Although students who have had prior counseling were found to have less fear of stigmatization, the degree of the fear did not predict whether that student held a positive or negative attitude toward counseling. Possibly efforts to reduce the stigmatization of mental illness and seeking mental health services on college campuses (Satcher, 2000) has had a positive effect on the college student population. The point should not be lost, however, that students who did not have prior counseling had a greater fear of being stigmatized by attending counseling, suggesting that getting students to engage in counseling in the first place is a significant step toward improving their attitude toward counseling.When the findings related to self-efficacy and being male are considered with the finding that fear of stigma was not predictor it seems that students, particularly male students, are less concerned about what others might think of them for needing mental health assistance and more concerned with what they will think about themselves for seeking mental health assistance. Counseling may be perceived as a threat to independence and competence for college students who are in the developmental process of taking greater control of their own lives. This threat may be felt more strongly among male students who are less likely to have had prior counseling experience and who may be less likely to recognize a need for counseling in their personal or academic lives.The largest contributor to the variance in college students' attitudes toward counseling was attributed to previous experience with counseling. As anticipated, students with prior counseling experience expressed more positive attitudes toward counseling.This result supports previous research that has shown that students are more likely to seek counseling help if they have had previous experience with counseling (Fischer & Farina, 1995). If prior experience with counseling can positively influence students' attitudes toward counseling, how can students, especially male students who generally have less prior experience, gain experience with counseling without first participating in counseling sessions? One avenue for students to gain experience with counseling may be through psycho-educational presentations that include counseling techniques for active listening, stress management, and problem solving. Once a student has had a glimpse of counseling and an experience with a counselor through a classroom or student organization presentation, it may be easier to seek professional psychological help.If acounselor is perceived as approachable and counseling is perceived as similar to the care and concern offered by friends and family, students' attitudes toward counseling may be positively influenced. Implications There are two significant implications from the present study. After college students have experienced counseling, their attitude appears to be more positive toward counseling and they fear being stigmatized less by the experience. These two variables, prior experience and reducing stigmatization, seem to make significant differences in whether a student will seek counseling services when that student has difficulty coping with life stressors or experiences a trauma or significant loss while attending college.Although male participants reported being less affected by fear of stigma related to psychological counseling, they had less prior experience with counseling than the female participants this study. Prior experience with counseling was the best predictor of attitude toward counseling in this study and attitude toward counseling has repeatedly been shown to be the best predictor of whether a student will seek or not seek counseling services.Based on these findings, it seems imperative for counseling professionals to make every effort to expand the range of occasions for meeting students in their role as helping professionals through classroom presentations, and participating in university activities that allow students a personal experience with counselors before they need them for more serious issues.

6. Recommendations

- Recognizing the continued low levels of both prior experience and attitudes toward counseling by men in the sample raises interesting questions about the differential socialization of women and men, especially related to the use of counseling services. Whether and how counseling professionals on university campuses might respond to the differential needs and experiences of students by age or gender seems a fruitful line of inquiry if universities are to help students make effective use counseling services on campus. Consistent with this recommendation, university counselors are encouraged to investigate the potential effectiveness of increasing students' experience with a counselor through semi-formal contacts, such as attending classroom presentations or campus workshops on career issues. Understanding that prior experience with counseling increases the likelihood of seeking services for more serious counseling-related issues underscores the necessity for university counselors to expand the range of their contacts with students as means to positively affecting their attitudes toward counseling based on the findings from this study, students are concerned with what others may think of them for seeking counseling assistance, but, it appears to affect them more deeply to admit to themselves that they need help from a counselor or from medication. Students who need help the most may be the least likely to seek out this help and this study was an attempt to better understand this phenomenon. Psychological help-seeking may be another area for this generation of students as Levine and Cureton (1998) has described "where hope and fear collide". As first responders to these collisions, faculty and student service professionals.Through utilizing psycho education, professional psychologists can reach out and help more people in need of health services. Using education in school settings, work environments, and within institutions with a wide range of different populations will also be important in determining what types of psycho education work best with certain groups. Using alternative forms of psychological Health Education like television programs or movies is one way to reach out to many different groups. Additionally, incorporating Mental Health Education into elementary and high school physical health classes may be a more effective means of changing people’s attitudes and level of stigma toward seeking psychological help.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML