-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2014; 4(5): 188-195

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20140405.03

Harmed or not Harmed? Culture in Interpersonal Transgression Memory and Self-Acceptance

Qingfang Song, Qi Wang

Cornell University, Ithaca

Correspondence to: Qi Wang, Cornell University, Ithaca.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study examined cultural effects on memory for interpersonal transgressions and the relation to self-acceptance. Asian and European American college students each recalled two specific incidents, one in which they hurt or wronged others (perpetrator memory) and one in which others hurt or wronged them (victim memory). Although both Asians and European Americans tended to minimize the harm in the perpetrator memory and maximize the harm in the victim memory, Asians exhibited a greater degree of harm minimization in both types of memories than did European Americans. Furthermore, for the victim memory, harm maximization (i.e., amplifying harms done by others) was negatively associated with self-acceptance for Asians, whereas harm minimization (i.e., downplaying harms done by others) was negatively associated with self-acceptance for European Americans. The culturally divergent implications of self-serving and relationship-serving biases in constructing interpersonal transgression memories are discussed.

Keywords: Keyword Culture, Interpersonal transgression memory, Self-serving bias, Relationship-serving bias, Self-acceptance

Cite this paper: Qingfang Song, Qi Wang, Culture and Interpersonal Transgression Memory: Harmedor not Harmed? Culture in Interpersonal Transgression Memory and Self-Acceptance, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 4 No. 5, 2014, pp. 188-195. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20140405.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- How people remember the interpersonal aspects of their lives can greatly influence their relationship satisfaction (e.g., Karney, & Coombs, 2000; Karney, & Frye, 2002), evaluations of themselves and others (Takaku, Green, & Ohbuchi, 2010; Wilson, & Ross, 2001), and subjective well-being (Kitayama, Markus, & Masaru, 2000). Although studies have examined factors that moderate people’s memory for interpersonal transgressions from the perspectives of the perpetrator and the victim (Feeney & Hill, 2006; Kraft, 2009), no study that we know of has taken into consideration the role of culture in shaping the remembering process (Wang, 2013). This study examined perpetrator and victim memories in Asian and European American young adults, and how the construction of such memories was related to individuals’ self-acceptance.Autobiographical memory is long-lasting memory for personal experiences “significant to the self-system” (Nelson, 1993; pp. 8). McAdams (2001) has argued that autobiographical memory entails an internalized and evolving story of the self for the construction of identity. Notably, such memory is not a mirror image of the reality but constructed in accordance with the self-system, whereby our knowledge, beliefs, self-goals and motive can profoundly influence what and how we remember our past experiences (Conway, 2000; Wang, 2013). One factor of the self-system, namely, self-serving motivation, may play a particularly important role in interpersonal transgression memory.

1.1. Self-serving Motivation

- Self-serving motivation, also referred to as self-enhancing motivation, drives people to focus on the positive aspects of the self and to evaluate the self optimistically so as to maintain or enhance positive self-regard (Heine & Lehman, 1995; Taylor & Brown 1988). It also drives people to ascribe successes to their personal qualities and attribute failures to external causes (Campbell & Sedikides, 1999; Mullen & Riordan, 1998). Pertaining to memory, studies have shown that people, especially those with high self-esteem and thus stronger self-enhancing motivation, remember their past successes better than failures (Silverman, 1964), and remember their task performance better than it actually was (Crary, 1996). Also, to fashion a positive self-appraisal, people deprecate past successes to accentuate their current achievements, and they subjectively distance unflattering experiences while feeling temporally close to favorable experiences (e.g., Wilson & Ross, 2001, 2003). In general, people selectively remember positive information that can boost their self-regard, while forgetting or misrepresenting negative information related to the self (for a review, see Sedikides & Gregg, 2003).The influence of self-serving motivation has also been observed in memories for interpersonal transgressions, whereby people often exhibit role-based biases for the purpose of maintaining a positive self-evaluation. Rather than taking responsibilities for a transgression that may shed negative light on the self, perpetrators who “hurt” or “wronged” others are more likely than victims to include happy endings, justify their behaviors, and diminish their culpability in their memory accounts of transgressions(e.g., Baumeister, Stillweli, & Wotman, 1990; Mikula, Athenstaedt, Heschgl, & Heimgartner, 1998). Victims, in contrast, tend to maximize the harm resulted from the perpetrators’ behaviors, describing perpetrators’ intentions as malicious and emphasizing negative outcomes and consequences. When participants were asked to retell ahypothetical story by identifying either with the perpetrator or the victim, similar discrepancies between perpetrator and victim accounts were confirmed (Stillweli & Baumeister, 1997). Thus, people selectively emphasize some aspects of an event and downplay the others in their memories to maintain favorable self-views, depending on the role they played in the event. The influence of self-serving motivation on interpersonal transgression memory may be further modulated by culture.

1.2. Culture, Self-Serving Bias, and Relationship-Serving Bias

- There has been mixed evidence regarding the cultural boundary of self-serving bias. Some researchers have argued that people from many Asian cultures do not exhibit self-serving biases, at least in some situations such as when dealing with failures (e.g., Heine, 2005; Heine, Lehman, Maukus, & Kitayama, 1999). Recent studies, however, have suggested that self-enhancing or self-serving motivation is universal and can be observed for culturally valued qualities (Sedikides & Gregg, 2003; Takaku et al., 2010). For instance, Asians, both native and overseas, consider themselves better on collective aspects of the self (Sedikides, Gaertner, & Toguchi, 2003) and evaluate more favourably their social traits than do North Americans (Ross, Heine, Wilson, & Sugimori, 2005), although they do not exhibit self-serving biases when judging their individual traits.The influence of self-serving bias on interpersonal transgression memory may take an interesting twist for Asians. On one hand, given the inherent social nature of transgression events, self-serving biases (i.e., minimizing harms done by oneself in perpetrator memories and maximizing harms done by others in victim memories) may still be apparent among Asians for whom maintaining positive self-regard in interpersonal contexts is of paramount importance (e.g., Ross et al., 2005; Yashima, Yamaguchi, Kim, Choi, Gelfand, & Yuki, 1995). On the other hand, given their relationship focus (Markus & Kitayama, 1991), Asians may further exhibita relationship-serving bias in their memory for interpersonal transgressions. Research has shown that people who greatly value their relationships are motivated to perceive others and their relationships in a positive light (e.g., Campbell, Sedikides, Reeder, & Elliot, 2000; Endo, Heine, & Lehman, 2000). When recalling transgression memories, they often make benign attributions for others’ wrongful behaviors, produce benevolent explanations for the transgressions, and construct memories in ways that enhance positive evaluations of others and the relationships (Fincham, Beach, & Baucom, 1987; Kearns & Fincham, 2005; Murray & Holmes, 1993, Murry, Holmes, & Griffen, 1996). Thus, relationship-serving motivation may drive Asians to minimize harms done by both themselves and others to promotesocial harmony. It will be theoretically informative to examine how self-serving motivation and relationship-serving motivation both play out in Asians’ interpersonal transgression memories, in contrast to those of European Americans.

1.3. The Present Study

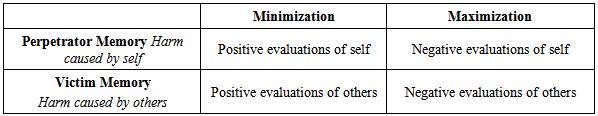

- The purpose of this study is to examine self-serving and relationship-serving biases in interpersonal transgression memories in a cross-cultural context. Asian and European American college students each recalled two interpersonal transgression memories in which they acted as either a perpetrator (perpetrator memory) or a victim (victim memory). Following prior studies (Baumester et al., 1990; Kearns & Fincham, 2005), the memories were coded for content categories that were then summed into two scores: the minimization score reflects the extent of downplaying the harms caused by an offender, and the maximization score reflects the extent of amplifying the harms caused by an offender. Accordingly, for the perpetrator memory in which the narrator him- or herself was the offender, minimizing the harm from the offender incurs positive evaluations of the self and maximizing the harm incurs negative evaluations of the self. For the victim memory in which the narrator was the victim and another person was the offender, minimizing the harm from the offender incurs positive evaluations of the other person and the relationship and maximizing the harmincurs negative evaluations of the other person and the relationship (See Table 1).

|

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- A total of 168undergraduate students at Cornell University participated in this study to receive partial course credits. They included 76 Asians (23 men and 53 women) and 92 European Americans (15 men and 77 women). Among the Asians, 33 were Chinese, 14 were Korean, 10 were Indian, 8 were of other East and South Asian cultural backgrounds, and 11 did not provide specific information. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Procedure and Measures

- Participants came to the lab in small groups of one to five and completed a booklet that contained instructions on the recall of interpersonal transgression memories and a number of questionnaires. Participants were asked to recall an incident in which “you hurt or wronged someone other than a romantic partner” (perpetrator memory), and an incident in which “someone other than a romantic partner hurt or wronged you” (victim memory). This method was adopted from Kearns and Fincham (2005). Participants were instructed to provide the full story of each event and include as many details as possible. They also indicated when each event occurred. The order in which participants reported different memories was counterbalanced.After the memory task, participants provided demographic information and completed a survey on psychological well-being (Ryff, 1989) that assessed self-acceptance. For each item (e.g., “When I look at the story of my life, I am pleased with how things have turned out”), participants indicated on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) how well that item described how they thought or felt. Negative items were reverse coded so that higher scores reflected more positive appraisals of the self. The scale was created by summing scores from 9 items, with a Cronbach’s alpha = .85.

2.3. Coding

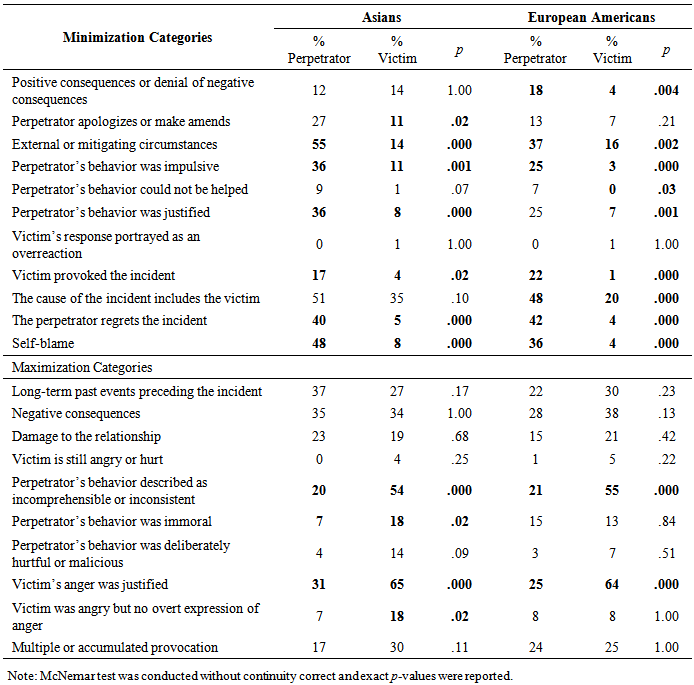

- To capture the content of the perpetrator memory and the victim memory, we adapted categories developed by Baumeister et al. (1990) to evaluate the presence (scored 1) or absence (scored 0) of a series of themes (see Table 2 for a list of the coding categories).Two coders independently coded 20% of the data for intercoder reliability estimate. Cohen’s Kappa across the 21 categories ranged from .53 to 1.0 (M= .91) for the perpetrator memory and from .65 to 1.0 (M= .90) for the victim memory. Two coding categories for the perpetrator memory (i.e., victim’s anger was justified, perpetrator’s behavior described as incomprehensible or inconsistent) had modest intercoder agreement (kappa < 0.6). However, when calculated in percent agreement, the intercoder reliability for the two categories was 83% and 86%, respectively, comparable with those in prior studies (e.g., Baumeister et al., 1990; Kearns, & Fincham, 2005). Disagreements between the two coders were dissolved through discussion. One coder coded the remaining data.

|

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

- In both cultural groups, the most commonly involved people in perpetrator memories were friends (50% Asian; 45% European American), family members (25% Asian; 28% European American), and acquaintances from school or workplace (24% Asian; 22% European American). The most commonly involved people in victim memories were friends (55% Asian; 61% European American), family members (8% Asian; 12% European American), and acquaintances from school or workplace (28% Asian; 22% European American). Chi-square analyses revealed no significant cultural differences in the types of people involved in either perpetrator memories, Χ2(4, N=168) = 3.82, p=.43, or victim memories, Χ2(4, N=168) = 4.01p=.41. The data from 4 participants whose perpetrator memory or victim memory involved romantic partners or who did not provide a perpetrator incident as requested were excluded from analyses.Participants’ ages did not differ significantly at the time when the perpetrator (mean age = 16.38 years, SD = 3.92) and victim incidents (mean age = 16.18 years, SD = 3.84) occurred, t(163) = .57, p =.57. The order in which participants recalled the memories (i.e., perpetrator memory prior to victim memory vs. victim memory prior to perpetrator memory) had effects on only 2 out of the total 42 content categories across the two memories. Memory order was therefore not considered further.Next we present results regarding the influences of memory type (perpetrator vs. victim) and culture (Asian vs. European American) on participants’ tendencies to minimize and maximize harms in their memory accounts. We then turn to the results concerning relations between harm minimization and harm maximization in memory accounts and self-acceptance.

3.2. Minimizing and Maximizing Harms

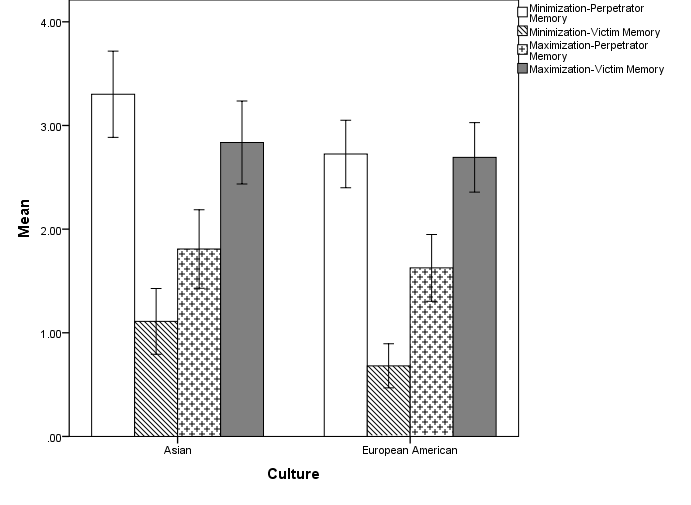

- A series of McNemar tests were conducted to examine the likelihood that participants referred to each memory content category as a function of memory type for Asians and European Americans, respectively. As shown in Table 2, there was a general tendency in which both Asian and European American participants were more likely to minimize the harm in the perpetrator memory than in the victim memory, and more likely to maximize the harm in the victim memory than in the perpetrator memory.We further conducted Fisher’s exact tests to examine whether there were cultural differences in the presence of each memory content category. Pertaining to perpetrator memory, Asians were more likely than European Americans to minimize the harm by describing the perpetrator’s apologies or amendment, p=.03, and including external or mitigating circumstances, p=.03, but to maximize the harm through the inclusion of long-term proceeding events, p=.04. Pertaining to victim memory, Asians were more likely than European Americans to minimize the harm by emphasizing positive consequences or denying negative consequences, p=.05, describing the perpetrator’s behavior as impulsive, p=.06, and attributing part of the cause to themselves, p=.03, but to maximize the harm by admitting their inner angry feelings, p=.06. Next, a 2 (memory type) x 2 (culture) mixed analysis of variance was conducted on the total minimization and maximization scores, respectively, with memory type as a within-subject factor and culture as a between-subject factor. For minimization, there was a main effect of memory type, F(1, 162)=192.02, MSE=1.89, p< .001, whereby perpetrators minimized the harm more than victims for both Asians, t(72) = 8.12, p< .001, and European Americans, t(90) = 12.20, p < .001. Culture effect was also found for minimization, F(1, 162) = 8.95, MSE = 2.28, p = .004, whereby Asians minimized the harm to a greater degree than did European Americans in both the perpetrator memory, t(164) = -2.20, p = .03, and the victim memory, t(132.43) = -2.36, p = .02. No significant interaction effect was detected, F(1, 162) = .23, MSE = 1.89, p = .63.For maximization, there was also a main effect of memory type, F(1, 162) = 58.26, MSE = 1.52, p< .001,whereby victims maximized the harm more than perpetrators for both Asians, t(72) = -4.75, p< .001,and European Americans, t(90) = -6.13, p< .001. The two groups did not differ in maximization in either perpetrator memory, t(164) = -.25, p=.80, or victim memory, t(164) = -.63, p = .53. No significant interaction effect was detected, F(1, 162) = .02, MSE=1.52, p=.89. Figure 1 illustrates the mean minimization and maximization scores as the function of memory type and culture.

| Figure 1. Mean frequency of narrative variables as the function of memory type and group. Error bars represent standard errors of the means |

3.3. Harm Minimization, Harm Maximization, and Self-acceptance

- There was no cultural difference between Asians (M = 4.31, SD = 0.72) and European Americans (M = 4.29, SD = 0.65) in the total score of self-acceptance, t(163) = -.20, p = .16. Zero-order correlations between self-acceptance and minimization and maximization scores were calculated for Asians and European Americans, respectively. For Asians, self-acceptance was negatively correlated with harm maximization in the victim memory, r = -.27, p= .02. In contrast, for European Americans, self-acceptance was negatively correlated with harm minimization in the victim memory, r = -.24, p= .02. No significant correlations were found for perpetrator memory (rs = -.18 to .02, ps = .12 to .88).

4. Discussion

- Prior research has demonstrated that perpetrators and victims construct interpersonal transgression memories differently in a self-serving manner (e.g., Baumeister et al., 1990; Kearns & Fincham, 2005; Stillweli & Baumeister, 1997). Yet there has been no study to investigate whether such biases are prevalent across cultures, in spite of the large literature concerning the interaction between culture and self-motivations in influencing cognition and behavior (Heine, 2005; Heine et al., 1999; Sedikides & Gregg, 2003). To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine self-serving and relationship-serving biases in interpersonal transgression memories as a function of culture, and the relation to self-acceptance.As we expected, Asian participants exhibited self-serving biases in interpersonal transgression memories similar to those of their European American counterparts. Participants of both cultures were more likely to minimize the harm in the perpetrator memory than in the victim memory, whereby they blamed victims for provoking the incidents, expressed their regrets and self-blame, and framed their behaviors as impulsive, justifiable, or excusable due to external or mitigating circumstances. Participants were also more likely to maximize the harm in the victim memory than in the perpetrator memory, whereby they described perpetrators’ behaviors as incomprehensible or inconsistent and justified victims’ anger. These findings add to the current debate concerning whether self-serving bias is pan-cultural, and suggest that individuals of Asian cultural backgrounds also remember themselves in a favorable light when the events are situated in interpersonal contexts. On the other hand, relationship-serving biases also emerged in Asians’ interpersonal transgression memories. Compared with European Americans, Asian participants downplayed interpersonal conflicts by minimizing the harm to a greater degree in both the perpetrator memory and the victim memory. This is in line with their motivation to promotesocial harmony and maintain positive views of others and interpersonal relationships (e.g., Sedikides et al., 2003; Ross et al., 2005; Endo et al., 2000).Analyses of individual memory content categories further revealed cultural differences in specific ways of minimizing interpersonal harms in memory accounts. In particular, compared with European Americans, Asians were more likely to refer to external or mitigating circumstances for their hurtful behaviors in the perpetrator memory, and also more likely to share the blame by admitting themselves as partly responsible for the incident in the victim memory. Prior research has shown that Asians, especially East Asians, are more inclined to attend to the broad context than European Americans, who tend to focus on the main characters and attribute their actions to their intentions (e.g., Chua, Leu, & Nisbett, 2005).It appears that by taking a holistic perspective, Asian participants viewed interpersonal conflicts as likely a result of external circumstances or shared responsibilities of all parties involved. In this way, they justified perpetrators’ behaviors and downplayed the severity of interpersonal harms.Interestingly, Asians were more likely than European Americans to refer to past events prior to the target incident in which they acted as a perpetrator. This may reflect Asians’ greater tendency to reflect on the past from a broad time frame to learn lessons and guide behaviors when remembering personal experiences (Wang, 2013; Wang & Conway, 2004). Asians were also more likely than European Americans to refer to their angry feelings in the victim memory. Anger, different from sadness, often focuses on the cause of a perceived goal failure (e.g., a relationship conflict) and motivates a goal reinstatement (e.g., to restore the relationship; Levine, 1995; Wang, 2003). This finding may therefore reflect the Asians’ greater expectation to reverse the perpetrator’s harmful behavior and restore social harmony. It may be fruitful to further examine the specific ways of minimizing or maximizing interpersonal harms in future memory research. Self-serving bias and relationship-serving bias in interpersonal transgression memories were further differently related to self-acceptance in the two cultural groups. As expected, Asians who made more harm maximization in the victim memory tended to have lower self-acceptance. Amplifying harms done by others is not conducive to relationship harmony and, for Asians who greatly value interdependence (Markus & Kitayama, 1991), negative self-evaluations may arise as a result. In contrast, European Americans who made more harm minimization in the victim memory, namely, those who exhibited less self-serving bias, tended to have lower self-acceptance. Downplaying others’ fault may imply that the self should be partially blamed for the incident and thus may result in negative self-evaluations. This finding is consistent with the general literature that among Westerners, people with higher self-esteem exhibit greater self-serving biases in memory than those with lower self-esteem (Crary, 1996; Silverman, 1964; Wilson & Ross, 2001, 2003). The relations of harm minimization and harm maximization to self-acceptance were only found for the victim memory, but not for the perpetrator memory in which one’s own transgression was at the center. Presumably, perpetrator memories may deal more directly with one’s moral weakness. Simply minimizing the negativity of the transgression or attributing part of the responsibility to the victim may not be sufficient to facilitate self-acceptance. Perhaps a more proactive approach to reconstructing the memories, such as to acknowledge self-weakness as common humanity (Leary, Tate, Adams, Batts, Hancock, 2007; Neff, 2010), to interpret the transgression as to promote self-growth (Lilgendahl, McLean, & Mansfield, 2013), or to provide mixed accounts that include both apology and mitigating and justifiable circumstances (Takaku et al., 2010), is required to foster self-acceptance.Notably, the relations of the memory biases to self-acceptance were based on correlational data. It is possible that reconstructing interpersonal transgressions in either a harm-minimizing or a harm-maximizing manner influences the level of self-acceptance, or self-acceptance may shape the way people remember interpersonal transgressions. To identify the direction and causality of the relationship, future studies can employ experimental manipulations to, for example, instruct participants to recall interpersonal transgression memories by using either harm minimization or harm maximization and then assess the effects on their subsequent states of self-acceptance. In summary, biases in constructing interpersonal transgression memories from the perspectives of perpetrators and victims are prevalent among both Asian and European American young adults to fulfill self-serving goals. Yet Asians, who ascribe greater importance to maintaining harmonious interpersonal relations, exhibited greater relationship-serving biases in both the perpetrator and victim memories, when compared with European Americans. Remembering interpersonal transgressions appears to have varied implications across cultures for psychological well-being.

Notes

- 1. Sixty-nine participants self-identified as Asian American and 7 self-identified as Asian. Analyses with or without the 7 participants yielded identical patterns of results. The final results were based on the entire sample. For simplicity, we refer to the sample as Asians.2. Participants also recalled a positive interpersonal event and answered questions on areas such as environmental mastery, positive relations, purpose in life, and autonomy. These data were for other research purposes and were not included in the current study.3. here were no significant effects of order in19 out of 21 content categories for perpetrator memory (ts = -1.78 to 1.86, ps = .07 to .96), or in all 21 content categories for victim memory (ts = -1.50 to 1.53, ps = .13 to .98). For perpetrator memory, the order had significant effects on the descriptions of perpetrator’s behavior as immoral and as not being able to be helped, ts = -2.17 and 2.02, ps = .03and .05.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML