-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2014; 4(3): 108-120

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20140403.05

Interrelations between Self-esteem and Personal Self-efficacy in Educational Contexts: An Empirical Study

Huy P. Phan, Bing H. Ngu

School of Education, The University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, Australia

Correspondence to: Huy P. Phan, School of Education, The University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, Australia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The present investigation extends previous studies, situating self-esteem within Bandura’s (1986, 1997) social cognitive theory. Our theoretical-conceptual model posits the impacts of the four major informational sources (e.g., enactive learning experience) on self-esteem; this postulation would, in part, advance our understanding into the nature of self-esteem. Furthermore, self-esteem is hypothesized to relate positively to the three levels of personal self-efficacy beliefs: global, course, and task. Academic engagement and achievement outcome, in turn, are postulated as adaptive outcomes of both self-esteem and self-efficacy. 350 12th grade students (200 girls, 152 boys) participated in this correlational study, and responded to a suite of Likert-scale inventories. We used causal modeling procedures to ascertain and decompose the direct and indirect effects. Some notable findings were established, which formulate a consideration for further advancement – for example, the direct influences from three of the four sources on self-esteem, and the impact of self-esteem on global self-efficacy.

Keywords: Academic engagement, Personal self-efficacy, Informational sources, Self-esteem, Secondary school learning

Cite this paper: Huy P. Phan, Bing H. Ngu, Interrelations between Self-esteem and Personal Self-efficacy in Educational Contexts: An Empirical Study, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 4 No. 3, 2014, pp. 108-120. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20140403.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

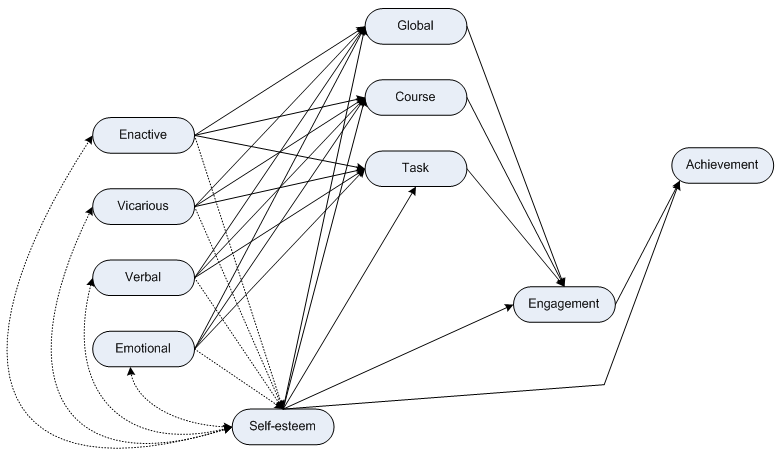

- The enhancement of quality learning is an important area of inquiry for consideration. Why do some individuals succeed, academically, despite their modest capabilities in classroom settings, and others do not? What motivational factors would contribute to individuals’ proactive engagement in schooling? How do we negate the potential detrimental consequences that could arise from low academic performances? These questions assist educators and policymakers in their articulations of educational-social programs that could promote and cultivate long-term well-being. Different theoretical orientations conceptualized over the past five decades have been explored and tested, involving individuals in different educational contexts. Perceived self-efficacy [1, 2] introduced in the late 1970s, for example, has been incorporated into different conceptualizations, and studied in academic and non-academic contexts, encompassing different educational levels [3-5]. Personal self-efficacy features prominently in human agency, and makes direct and indirect contributions to the prediction of learning in achievement contexts [e.g., 6, 7-9]. Another noncognitive construct that has featured prominently is one’s personal self-esteem [10, 11]. One’s own sense of self-worth (e.g., I am a good person), similar to self-judgments of perceived competence, is an important self construct that serves to enhance and predict achievement-related outcomes and adaptive practices. Both self-esteem and self-efficacy, in this case, form part of the wider self-system that also includes self-concept [12-14]. The relevance of self-esteem in educational contexts has been acknowledged by a number of researchers [15-17]. To what extent do self-esteem and self-efficacy differ, characteristically, and how do these two self constructs relate and function to influence student learning? In the context of the present study, we choose to situate self-esteem within the framework of social cognition [2, 18], including its impact on personal self-efficacy, structured at different levels of specificity, and academic engagement and achievement outcome. Notably, differing from previous research investigations, the theoretical-conceptual model that we have developed for the present study incorporates an examination of the influences of different informational sources on both self-esteem and personal self-efficacy. This avenue of inquiry, especially in relation to the formation of self-efficacy [e.g., 19, 20-22] is theoretically insightful, and may yield fruitful information regarding the nature and characteristics of both self constructs. Does an individual’s enactive learning experience (e.g., repeated successes) help to heighten his/her self-esteem? Does self-esteem make a meaningful contribution to the overall variances of the different levels of self-efficacy? These research questions, in totality, form the basis for our theoretical-conceptualization, detailed in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Conceptual Model for Examination |

2. A Theoretical-Conceptual Framework: Formation of Personal Self-efficacy

- Figure 1 depicts the developed theoretical-conceptual for this investigation. This articulation, drawn from existing theoretical tenets [2, 18] and research evidence, entails an amalgamation of four major strands of inquiry: (i) formation of self-efficacy, (ii) the impact of self-efficacy on academic engagement, (iii) the impact of academic engagement on achievement outcome, and (iv) the importance of self-esteem. This unification in research inquiries is integral to our understanding of the genesis of personal self-efficacy and the enhancement of learning in achievement contexts. More importantly, however, empirical validation quantitatively from secondary school learning may illuminate some notable pedagogical strategies and instructional practices for consideration.

2.1. The Formation of Personal Self-efficacy

- Personal self-efficacy, introduced in the mid-1970s [1], emphasizes the importance of the self and one’s own perceived competence. Bandura’s (1977) seminal article, titled ‘Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change’, introduces the concept of self-efficacy and its features in the prediction of individuals’ quality learning in motivation contexts. Since then, there has been a plethora of research studies that delve into the potency of self-efficacy in academic and non-academic settings [2, 3]. Self-efficacy, defined as “beliefs in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments” [2], is an important self-evaluation process that influences individuals’ behaviors – for example, the choice that one makes in life (e.g., an individual opting to study a vocational course). Self-efficacy assists individuals in their mobilization of effort on a learning activity, resilience in the face of adverse situations, and persistence when confronting obstacles. Furthermore, according to Bandura (1997), self-efficacy influences individuals’ thought patterns and emotional reactions – for example, a weakened sense of self-efficacy entails a perception that things are tougher than they really are, leading to stress, depression, and a restricted view as to how one would solve a problem [3]. A heightened sense of self-efficacy, in contrast, creates the feeling of serenity when one approaches difficult tasks and activities. Self-efficacy, according to Bandura (1997), differs from other forms of self-beliefs (e.g., self-esteem) for its contextual nature. Self-efficacy may reflect one’s perceived sense of competence to attain and produce results at a global, course, and/or task level. Self-efficacy for academic learning, in this sense, differs from the nondescript term ‘confidence’, as it entails “both an affirmation of a capability level and the strength of that belief” [2]. Confidence, in contrast, is relatively vague, as this belief does not necessarily specify what the certainty is about (e.g., “I can be supremely confident that I will fail an endeavor”).The question relating to the formation of personal self-efficacy is important, and Bandura (1986, 1997) theorizes that there are four major antecedents, in their order of potency, which shape and form self-efficacy: enactive performance accomplishment, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion, and emotional and physiological states. Foremost, according to social cognitive theory, is the relevance and application of one’s personal learning experiences, authentically and experientially based, and subject to mastery and normative criteria. Performance-based successes, especially those subject to mastery criteria help strengthen a person’s sense of self-efficacy. Repeated failures, in contrast, tend to dampen one’s own self-efficacy state with profound subsequent adverse effects. Less important, however, is the impact of vicarious experiences on personal self-efficacy [2]. Information derived vicariously encompasses role modeling and social comparison. Observing a peer’s academic success, for example, motivate one’s own effort to work hard. At the same time, of course, such modeling of a peer’s competence may instill confidence and heighten self-efficacy towards a similar task. Verbal persuasion features relatively less in individuals’ recognition and cognitive appraisal of ability. This source of information may include a wide range of verbal discourses, such as attributional and evaluative feedbacks expended by capable others. Finally, least important is the impact of physiological and emotional states, which serve as indicators of capableness, strength, and vulnerability to dysfunction. A high state of anxiety, in this instance, reflects a weakened sense of personal self-efficacy. Research into cognitive appraisal and the impact of varying sources of information is relatively complex. Since the 1990s, there has been a plethora of research investigations that utilize quantitative methodological approaches to study the formation of personal self-efficacy. A few research studies, albeit limited in nature, have also used qualitatively methodological approaches to explore the underlying processes of cognitive appraisal of different informational sources (e.g., selection of appropriate source) [e.g., 23]. From a quantitative perspective, in contrast, the use of Likert-scale measures with participants at different educational levels, ranging from elementary school students [e.g., 24] to those cohorts at universities [e.g., 19, 20] has yielded some notable evidence. Importantly, in relation to existing research, there have been two major strands of inquiry: (i) the factor structures of sources of self-efficacy [e.g., 24, 25, 26], and (ii) the impact of informational sources (e.g., enactive learning experiences) on personal self-efficacy [19-21]. Relevant to the present investigation, the inquiry pertaining to the potent effects of different informational sources has produced clear and consistent findings to support the present proposition. Self-report responses from Likert-scale questionnaires indicate, for example, the prominent impact of enactive learning experiences [e.g., "I have always had a natural talent for maths": 19] in the formation of personal self-efficacy [19, 21, 22, 27-29]. Individuals emphasize their preference for the gauging of personal successes and failures, subject in this case to both mastery and normative evaluation criteria. Consistent with Bandura’s (1986, 1997) theorization, there is also evidence to indicate the marginal influences of vicarious experiences [20, 21, 28], verbal persuasion [22], and emotional arousal and physiological states [22, 28]. Combined with previous evidence, it is obvious that individuals resort to different informational sources in the formation of personal self-efficacy. Of course, the predictive effects ascertained from multivariate statistical procedures alone do not indicate the complexities that espouse the selection, weighing, and integration of different informational sources [2, 23]. We do concur, however, with existing evidence, arising from regression and causal modeling procedures regarding the study and advancement of antecedents of personal self-efficacy [2].

2.2. Consequences of Personal Self-efficacy

- Consequences of personal self-efficacy [2] entail a different strand of research inquiry, encompassing a variety of methodological approaches. Social cognitive theory [2, 18] indicates the explanatory and predictive power of self-efficacy in both educational and non-educational contexts [3, 30]. A heightened sense of personal self-efficacy, in this case, facilitates the mobilization of effort expenditure, persistence, and affective responses (e.g., a decrease in anxiety) to assist individuals’ successes. Weakened self-efficacy beliefs for academic learning, in contrast, negate learning-related attributes (e.g., inclination towards work avoidance) and dampen one’s performance outcome. Bandura’s (1986, 1997) theoretical tenets (e.g., the predictive effect of personal self-efficacy), in general, have been tested and validated by a number of scholars. A synthesis of the literature indicates, for example, the analogous interrelations between self-efficacy, academic achievement, and a myriad of cognitive-motivational processes: study processing and achievement goal orientations [7, 29, 31]; and perceived usefulness, self-concept, problem solving, apprehension, and anxiety [32-36].Evidence attesting to the potency of personal self-efficacy supports the inclusion of other adaptive practices and achievement-related outcomes for advancement. In the context of the present investigation, we select the construct of academic engagement for examination given its characteristics [37-40]. In the field of educational psychology, for instance, there is a plethora of research studies that emphasize the direct impact of academic and school engagement on quality learning and performance outcome. Engagement is relatively diverse in scope [40, 41] and may be defined as “the extent to which students identify with and value schooling outcomes, and participate in academic and non-academic school activities” [37]. Academic engagement, according to researchers [40, 41], espouses a number of cognitive-motivational attributes, such as effort expenditure, pride, enthusiasm, and engrossment. Academic engagement, as research has shown, is a dynamic psychosocial construct that facilitates quality learning in achievement contexts [37, 40]. Disengagement, in contrast, may lead to detrimental consequences and maladaptive practices [29, 38, 42-44].

3. A theoretical-Conceptual Model: Personal Self-efficacy, Engagement, and Achievement

- The study of personal self-efficacy [2, 18], as detailed previously, is supported by substantial research. There is clear and consistent evidence to warrant advancement in the integration of different strands of inquiries, notably: the formation of personal self-efficacy [e.g., 19, 21, 45], and the consequences of heightened self-beliefs for academic learning [e.g., 6, 7, 29, 46]. The theoretical-conceptual model developed for examination (See Figure 1) entails the amalgamation in research findings of the two mentioned strands of inquiries. Causal modeling procedures [47, 48], in this case, may yield findings that identify the genesis of personal self-efficacy. Furthermore, contributing to the study of social cognition [2, 18], we include academic engagement [37-40] as an adaptive outcome of self-efficacy. The present study, in addition to the mentioned emphasis (e.g., the formation of personal self-efficacy), signifies two major aims: (i) the inclusion self-esteem [15, 17] as a potential antecedent of academic self-efficacy, and (ii) the differentiation of self-efficacy into different levels of specificity [2, 3]: global (e.g., “I feel that I have the perceived competence to do well, academically, at school”), course (e.g., “I feel that I have the perceived competence to obtain an A grade for the unit ECO101”), and task (e.g., “I feel that I have the perceived competence to solve this set of econometric problems”). The self-systems consist of different self-beliefs, such as self-esteem, self-concept, and self-efficacy. A conceptualization, in this case, may connote an overarching system, whereby self-esteem functions as an antecedent of more-contextualized self-beliefs.

3.1. Emphasis on Self-esteem

- Self-esteem, defined as “an individual’s sense of value or self-worth, or the extent to which people value, appreciate or like themselves” [15], may operate to influence cognitive appraisal of information. Bandura’s (1997) social cognitive theory acknowledges the potential association between self-esteem and self-efficacy. J. Lane, et al.’s (2004) research involving postgraduate students found that self-efficacy was associated positively with self-efficacy to maintain motivation in the face of difficulties (α = .28, p < .05), self-efficacy to cope with intellectual demands (α = .31, p < .05), and self-efficacy to obtain at least a pass in a unit of study (α = .37, p < .05). Phan’s (2010) research study, differently somewhat, reported a predictive effect of self-esteem on self-efficacy (β = .25, p < .01). What is interesting then, for consideration, is the study and validation of self-esteem concurrently with the four major informational sources on self-efficacy: enactive learning experience, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion, and emotional and physiological states. Importantly, in relation to our research focus, the impact of self-esteem on different contextualized self-efficacy measures (e.g., global self-efficacy) is warranted. We posit that self-esteem, given its generalized characteristics (e.g., sense of self-worth), would relate more closely to global self-efficacy beliefs (e.g., perceived competence to do well, academically, in mathematics). In a similar vein, however, contributing to the empirical literature is the potential impact of the four sources of self-efficacy on self-esteem. Enriched learning experiences, such as ongoing successes in a subject matter are more than likely to instill a sense of self-worth. Individuals’ sense of self-worth, in turn, may facilitate and heighten specific and contextual self-beliefs for learning. This stipulation (i.e., the impacts of informational sources on self-esteem) is exploratory, given there is no research we know of that has advanced the study of informational sources and self-esteem.

3.2. The Potency of Specificity

- The specificity of personal self-efficacy is a specific and important topical theme, according to Bandura (1986, 1997). Its contextual nature (e.g., perceived competence at a global level), a research inquiry in social cognition, has led to a methodological focus involving the development of different subscales of items. Quantitatively, for example, self-efficacy measures in a subject matter may entail a Likert-scale rating, say: “I believe I will receive an excellent grade in this class” [e.g., Item 5: 49]. Self-efficacy items, as we mentioned previously, may encompass different levels of specificity: global, course, and task. A number of research studies have, as a result, explored the different levels of specificity concurrently within one study (e.g., do global, course, and task-specific self-efficacy beliefs all exert positive effects on mathematics learning?) [e.g., 50, 51, 52]. The inclusion of specific self-efficacy measures for examination is significant, especially in light of our focus on the four major antecedents. For example, to date, very little is known about the formation of differing levels of specificity of personal self-efficacy. Do the four informational sources, theorized by Bandura (1986, 1997), vary in their influences on different levels of self-efficacy beliefs? We contend that enactive learning experiences may not necessarily make a significant impact on task-specific self-efficacy, especially when previous successes are based on differing attributes and criteria that do not necessary relate to or reflect atomistic self-beliefs. Similarly, verbal discourse (e.g., attributional feedback) specific to a particular microanalytical concept (e.g., encouraging individuals to persist and master the key emphasis of Algebraic equations involving an unknown x) may relate more closely to task-specific self-efficacy beliefs. This inquiry overall, expanding existing research findings [e.g., 19, 21, 22, 27], has theoretical merits, especially in relation to the formation of differential self-efficacy judgments.

3.3. The Predictive Effects of Differential Self-efficacy Beliefs

- The emphasis pertaining to differential self-efficacy judgments also lends itself to varying influences on academic learning and achievement-related outcomes. There is some evidence to support the conceptualized framework that depicts the impact of self-efficacy, assessed at different levels of specificity, on academic achievement [50, 51]. In tandem with this avenue of inquiry is the issue of constructive alignment [2, 3], detailing the close correspondence between self-efficacy and performance- based items [52]. Contributing to this focus, the present investigation stipulates the contribution in predictive effects of self-esteem and the three levels of personal self-efficacy on academic engagement and achievement outcome. This focus, from our point of view, revisits prior findings [e.g., 6, 15, 50, 51, 53], and is of theoretical significance. Such analyses, in particular, may yield comparative indications of predictive effects of different levels of self-beliefs. Apart from achievement outcome in a subject matter, it is prudent for us to consider the predictors and enhancers of academic engagement. Why do some individuals engage more than others in their schooling and/or extracurricular activities? What extraneous factors and/or detrimental consequences that may negate academic engagement? The inclusion of academic engagement as an adaptive outcome of self-beliefs (e.g., self-esteem) is notable and extends previous research examinations for consideration. Foremost, of course, as we outlined in the preceding sections, is the positive consequence of engagement itself [38-40, 54]. From a psychological perspective, in particular, an emphasis on academic engagement may generate some evidence that could inform educators of the potentials of academic engagement.

4. Methods

4.1. Procedure and Sample

- Participants were 352 grade 12th students (200 girls, 152 boys) from four government schools located in Central Nadi. We sought permission from a number of principals and teachers to allow us to administer the questionnaires in intact tutorial classes, and to collect the participants’ academic results for the subject mathematics. We followed strict ethical protocols, especially in relation to the subject of anonymity, confidentiality, and the choice to withdraw from the study without any required explanation.

4.2. Instrumentations

- Sources of Self-efficacy. A 20-item scale, developed by us and published in previous research [55, 56], is used to assess the four major sources of self-efficacy. There are four corresponding subscales, with each subscale containing five items and rated on a seven-point Likert-scale (1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree)). The items included, for example: ‘I always get good marks from my teacher for this subject’ (enactive performance accomplishments), ‘I admire and respect those students in my class who are successful, academically’ (vicarious experiences), ‘I have been praised for my ability in this subject’ (verbal persuasion), and ‘This subject makes me stressed and nervous’ (emotional and physiological states). Academic self-efficacy. The Academic Self-efficacy Questionnaire (ASQ) for academic learning, similar to previous research and inventories [49, 57], was developed by us to assess and measure self-efficacy beliefs at different levels of specificity, in particular: Global (e.g., ‘I am confident about my ability to do mathematics’; three items), Course (e.g., ‘I am confident about my ability to obtain a good grade for the topic Algebra’; six items), and Task-specific (e.g., ‘I am confident that I can solve this set of Algebra problems – for example, x2 + 11 = -25; solve for x’, 16 items). The 25-item scale (rated: 1 (not true at all of me) to 7 (very true of me)), as reported in previous published work [55, 56], reflects sound psychometric properties. Self-Esteem. We used the Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale [11] to assess individuals’ well-being. The 10 items, rated on a seven-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 7 (‘strongly agree’), include, for example: ‘On the whole, I am satisfied with myself’ and ‘I wish I could have more respect for myself’.Academic Engagement. We used 11 items, rated on a 7-point Likert-scale (1 (completely disagree) to 7 (complete agree)), from existing inventories [58-60] to assess academic engagement. Two of the items are worded positively (e.g., ‘I look forward to learning more about this subject, mathematics, in the future’) and nine negatively (e.g., ‘I often find excuses for not starting the work for this mathematics class’).Academic Achievement in Mathematics. We used two indexes to define academic achievement in mathematics: (i) school term coursework results (e.g., consisting individual, periodic quizzes), and (ii) a 30-minute quiz, consisting of 15 questions for solving (e.g., divide 4x3 – 19x + 9 by 2x – 3). A number of iterations were made in the development of the quiz to ensure quality and consistency for all participants. We sought advice from the teachers as to what contents should and could be included for coverage. This deliberation, from our point of view, would warrant fairness and enable all participants to participate in the quiz.

5. Data Analyses

- We used path analytical procedures [47, 48], assisted with the statistical software package LISREL 9.1, to explore and validate two competing, non-nested models. This statistical approach differs from other multivariate techniques (e.g., regression modeling) for its flexibility to allow researchers to test direct and mediating effects. Appropriateness of a particular model, in this case, is determined by the various goodness-of-fit index values – for example, the Chi-square statistic (χ2), the Steiger-Lind root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) [61] with its 90% confidence interval, the Bentler Comparative Fit Index (CFI) [62], and the Non-normed Fit Index (NNFI) [63]. The major model for statistical testing involves specifically:• The four major informational sources exert positive effects on self-esteem and the three levels of self-efficacy.• Self-esteem serves as an antecedent of the three levels of self-efficacy (e.g., global self-efficacy).• The three levels of self-efficacy exert positive effects on academic engagement and, in turn, engagement influence achievement outcome.

5.1. Structural Analyses

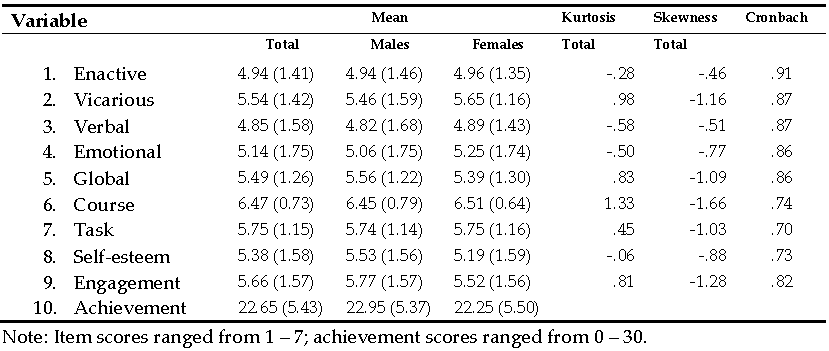

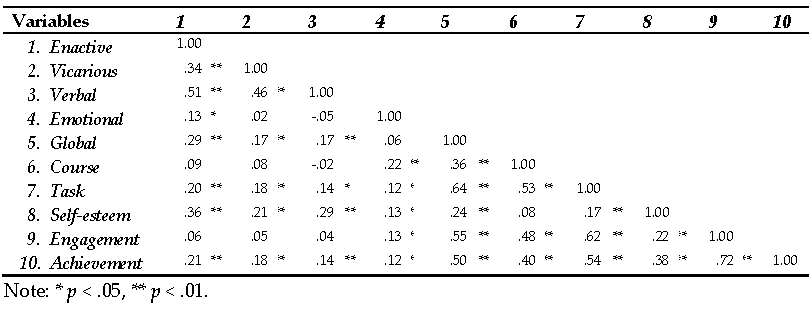

- Per protocols [47, 48], we used covariance and not correlational matrix as the latter has been known to cause a number of problems, such as producing incorrect goodness-of-fit index values and standard errors [64]. Given the multivariate normality of the data, we also used the preferred maximum likelihood (ML) procedure [65]. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics, including Cronbach’s alpha values for the mentioned constructs. The kurtosis values ranged from -.58 to 1.33, whereas the skewness values ranged from -1.66 to -.46. Similarly, the mean scores for the mentioned variables ranged from 4.85 (SD = 1.58) to 6.47 (SD = .73). Table 2 presents the correlations among the variables, including achievement for consideration in the subsequent path analysis.

| Table 1. Descriptive Statistcs |

| Table 2. Correlations among variables |

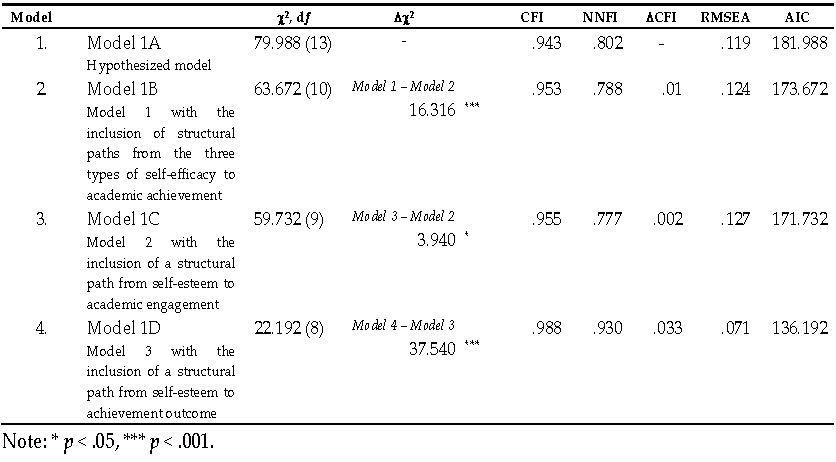

| Table 3. Goodness-of-fit Index Values |

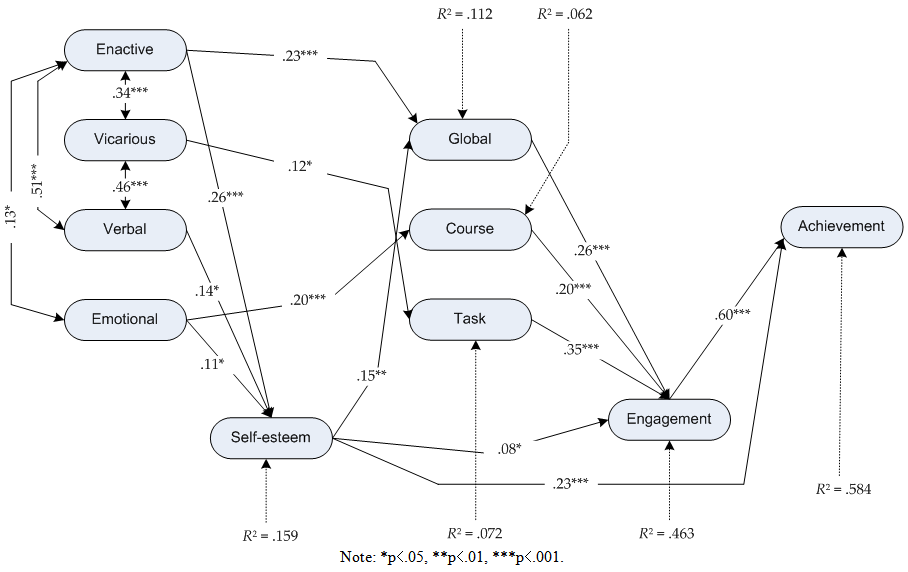

| Figure 2. Final Solution Depicting Interrelations between Informational Sources, Self-Esteem, Self-Efficacy, And Adaptive Outcomes |

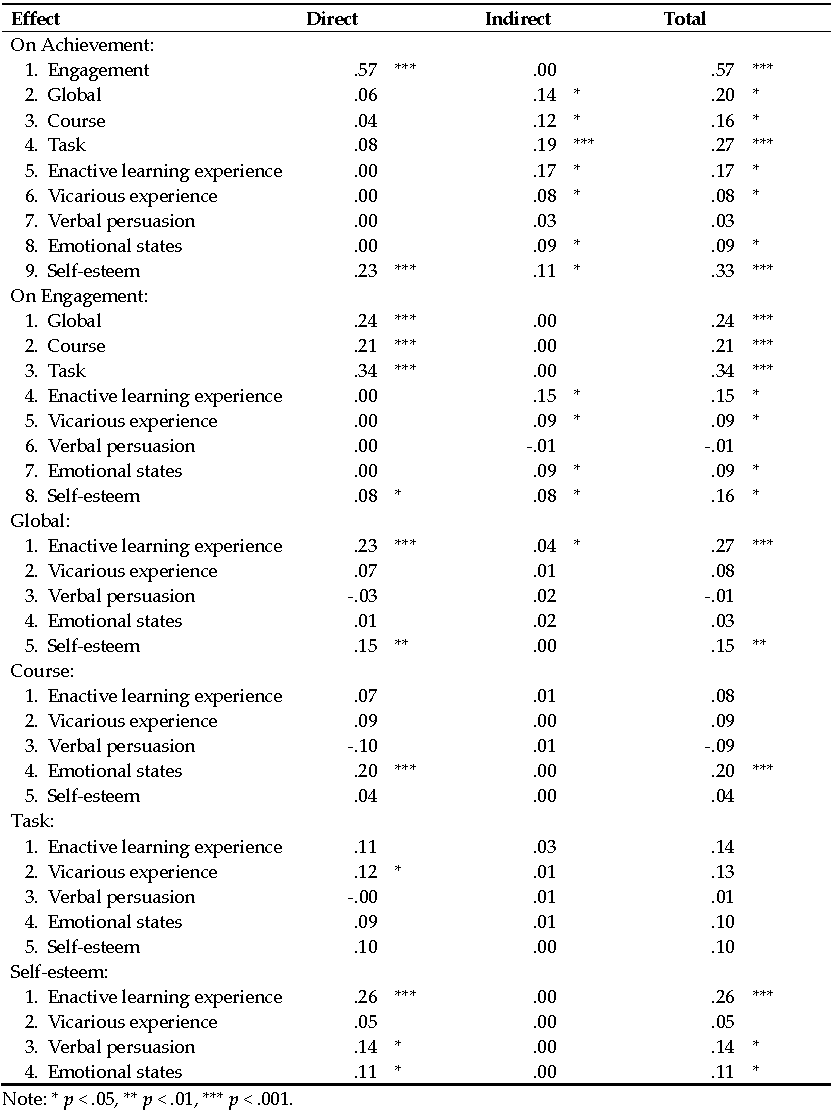

| Table 4. Direct, Indirect, and Total Effects |

6. Discussion of Findings

- The present investigation utilized social cognitive theory [2, 18] as a theoretical basis in the study of academic engagement and student learning. Extending previous research inquiries, the focus of our examination emphasized the importance of various levels of self-beliefs and their potent influences on academic engagement and achievement outcome in mathematics. Evidence ascertained from path analytical procedures has made a theoretical contribution, especially in relation to the formation of both self-esteem and various levels of personal self-efficacy [2, 3, 68]. The use of path analytical procedures [47, 48], in this case, has enabled us to present and test different non-nested conceptualizations. This ‘exploratory’ approach in causal modeling procedures is rather innovative, as it provides empirical insights into different possibilities and interactions between motivational variables. We emphasize this methodological, exploratory approach based on our examination of the literature. One specific inquiry that arises from our review of the literature, in particular, entails the featuring of self-esteem in a system of change. Its formation and hierarchical relations with personal self-efficacy, structured at different levels of specificity [2, 50], is a major focus for consideration. How does self-esteem relate to the four major sources of self-efficacy? How do individuals formulate their self-esteem in educational contexts?

6.1. Interrelations between Informational Sources, Self-esteem, and Personal Self-efficacy

- Analyses of the data, based on secondary school students’ responses, have generated results that support our hypotheses. As we described previously, one notable research aim entailed the positive impacts of enactive learning experience, verbal persuasion, and emotional and physiological states on self-esteem. This key evidence indicates, for our consideration, the similar process of forming of self-esteem to that of personal self-efficacy [2, 18]. Self-efficacy, in this case, is formed disparately from three of the four sources: enactive learning experience relates to global self-efficacy, whereas emotional and physiological states and vicarious experience relate to course and task-specific self-efficacy, respectively.The obtained findings regarding the influences of sources of self-efficacy contribute, theoretically and empirically, to the existing literature. Comparing with previous results [e.g., 19, 21, 22, 27, 45], in particular, we note that not all four sources make a predictive contribution to the prediction of personal self-efficacy. For example, Lent, et al.’s (1991) study, similar to the work of Britner and Pajares (2006), found that only enactive learning experience made a statistical significant contribution to the prediction of self-efficacy. In relation to the predictive effects on self-efficacy, consistent with previous research investigations [19, 21, 22, 45], enactive learning experience is also found to account for the greatest proportion of the variance in self-efficacy. This emphasis of enactive learning experience, likewise, features predominantly in the formation of self-esteem. Educationally, in this instance, it would serve beneficially for educators to consider instructional and pedagogical practices that emphasize the saliency of mastery and enriched learning experiences.The formation of self-esteem is interesting somewhat, especially given that we situate this aspect of inquiry within the social cognitive framework [2, 18]. The influences of enactive learning experiences, verbal persuasion, and emotional and physiological states on self-esteem have elucidated some major theoretical insights, providing a premise for further research examination. This evidence, we believe, has also added support regarding the featuring of self-esteem in an educational system of change. Enriched learning experiences, subject to both mastery and normative evaluative criteria, in this instance, may encourage and instill a positive sense of self-worth. Individuals who face repeated failures, in contrast, are more likely to experience a sense of helplessness and feelings of inferiority. In a similar vein, apart from personal learning accomplishment, social discourse may also serve to instill and strengthen one’s self-esteem. Encouraging feedback, for example, may serve as an incentive to make individuals feel good about themselves and their capabilities. Discouraging comments, likewise, are more than likely to weaken one’s self-worth about himself/herself.The hypothesis relating to the interrelations between self-esteem and the different levels of personal self-efficacy is supported, in part, from our findings. Self-esteem is found to relate positively to global self-efficacy, but not the other two levels of self-efficacy beliefs. A few researchers have studied, quantitatively, the relations between self-esteem and self-efficacy [15-17], incorporating a theorization that subsumes both constructs within a larger system of the self. Interestingly, from our analyses, the differential impact of self-esteem on global self-efficacy (β = .15, p < .01) and not course or task-specific self-efficacy raises questions for consideration. One explanation, which we also used a basis to support our hypothesis, is the fact that both self-esteem and global self-efficacy are more ‘global’ and non-atomistic in their characteristics and nature.

6.2. Self-beliefs, Engagement, and Academic Outcome

- Contributing theoretically to the scope of student learning, we focus on the impacts of self-esteem and self-efficacy, structured at different levels of specificity, on both engagement and achievement outcome. The emphasis on engagement, especially the potential influences from the three levels of personal self-efficacy, is of significance. Previous research in the area of personal self-efficacy, for example, has focused predominantly on a specific level of self-perceived judgments (e.g., course-level self-efficacy) [e.g., 7, 29, 34, 69, 70]. A few studies, quantitatively, have also explored concurrently the different levels of self-efficacy (e.g., global versus course self-efficacy) within one theoretical-conceptual framework [50]. The focus of contextualized self-efficacy beliefs in educational settings provides a theoretical insight into the operational functioning of differential effects on adaptive outcomes (e.g., academic engagement). Instructional practices in academia may, in this case, revolve at executing a certain course of action – for example, accomplishing success in a set of problems for a subject matter. It is interesting to note that the three levels of personal self-efficacy did not influence achievement outcome, but exerted direct effects on academic engagement instead (β values ranging from .20 - .35). This evidence is illuminative, emphasizing the nature and characteristics of contextualized self-efficacy beliefs for academic learning. Self-efficacy beliefs, as previous research studies have shown [e.g., 7, 29, 69, 71], do not necessarily relate directly to academic achievement. The dichotomy in differential self-efficacy beliefs (e.g., global versus atomistic), in this case, seems to converge and manifest similar predictive effects. Importantly, perhaps, this evidence highlights the complexity and multifaceted nature of academic engagement [40, 41]. Schaufeli, et al. (2002), for example, advocate that engagement encompasses mental resilience and willingness to invest effort in learning [e.g., 'I am very resilient, mentally, as far as my studies are concerned' (vigor): [41]. Self-efficacy beliefs at different levels of specificity, in this sense, involve the mobilization of effort expenditure, persistence, etc. [2]. The three levels of self-efficacy, in this case, influenced academic outcome indirectly, via academic engagement (e.g., β = .15, p < .05 for global self-efficacy → achievement outcome). In a similar manner, self-esteem is shown to exert an indirect effect on achievement outcome, via academic engagement (β = .11, p < .001). This finding is pivotal, emphasizing academic engagement as a central construct of learning-related outcomes. Consistent with previous theoretical contentions [29, 38, 40], academic engagement is found to relate positively to achievement outcome. Individuals who are engaged [e.g., ‘I look forward to learning more about this subject, mathematics, in the future’: 60], academically, are more likely to progress and achieve in their academic learning. In this sense, from an educational perspective, it is advantageous to use engagement as an intervention to encourage and foster adaptive outcomes. What psychosocial and/or motivational factors serve to encourage and enhance academic engagement? There is a plethora of research studies that have yielded similar findings [e.g., 29, 59], suggesting a number of psychosocial facets that could cultivate and encourage proactive engagement (e.g., a perceived sense of school belonging). Self-esteem also exerted a small direct effect on academic engagement (β = .08, p < .05), and differing from personal self-efficacy, influenced achievement outcome directly (β = .23, p < .001). The analogous association between self-esteem and adaptive outcomes, such as academic engagement and achievement outcome reflects similar findings that have been established in previous research studies [15, 16]. The importance of self-esteem also rests in its indirect association with academic engagement, via global self-efficacy (β = .08, p < .05). Educationally, similar to personal self-efficacy [2, 18], it is advantageous for us to consider its cultivation and enhancement. Coupled with our previous findings involving informational sources, one potential avenue for consideration is the strengthening of enactive learning experiences. Enjoyment for learning (e.g., seeking mastery) and subsequent enriched learning experiences, subject to various criteria, as shown from our investigation, are likely to instill and heighten one’s self-esteem. There are of course other means, including the use of encouraging and persuasive feedback to instill positive self-esteem. The indirect effect of self-esteem on academic engagement, via global self-efficacy is consistent with Bandura’s (1997) social cognitive theory and previous evidence [e.g., 6, 7, 8, 34], indicating the potent central role of personal self-efficacy in the learning process. A heightened sense of global self-efficacy, for example, mobilizes individuals’ effort expenditure to engage more proactively in a learning context. The triarchic associations between self-esteem, global self-efficacy, and engagement, in this sense, illuminate the importance of positive self-beliefs in academic learning. There are a number of educational implications for consideration, especially in terms of applied and instructional practices. The notion of positive psychology and one’s long-term well-being is an area of research interest [72-74], and as such, various self-beliefs and their interrelationships have been noted to make a significant contribution.

7. Conclusions

- The key findings arising from the present investigation have made progress and have contributed, theoretically, to the study of positive self-beliefs in the learning process. Within one theoretical-conceptual framework based on social cognitive theory [2, 18], integrating different strands of research inquiries, we explored the interrelatedness between self-esteem and personal self-efficacy, structured at different levels of specificity. Taken together, the present study has made contributions, providing a premise for substantial advancement into the functioning and characteristics of both self-esteem and self-efficacy. There are, however, a number of potential limitations for consideration, which provide direction for further research. Firstly, the data drawn from this investigation were based on a cross-sectional design, and utilized a self-report methodological approach. The weighing and impact of informational sources on personal self-efficacy and/or self-esteem is complex, and self-report measures are somewhat limited in capturing empirical insights into the underlying process of cognitive appraisal. The impact of enactive learning experience on self-esteem, for example, requires data derived from other additional means [23]. The work of Lent, Brown, et al. (1996) using a thought-listing methodological approach, in particular, has generated findings (e.g., the weighing of informational sources) that illustrate the effectiveness of non-quantitative methodological approaches in the study of sources of self-efficacy. The established association between self-esteem and global self-efficacy, similarly, is rather complex and our explanation, at present, is relatively limited. The particular interest, in this case, entails the potential hierarchical structuring of the various self constructs, based on our investigation and previous findings [15, 16, 50, 51]. There has been, in this instance, scholarly research and theoretical reviews pertaining to similarities and differences of self-concept versus personal self-efficacy [e.g., 50, 51, 66, 75]. Researchers could extend this avenue of inquiry to include a comparison of other self constructs, such as self-esteem and self-confidence. In relation to such theoretical contention and conceptualization, it would add credence to also include other achievement-related outcomes. The predictive effects differ between self constructs (e.g., self-esteem versus self-confidence), and it would assist in the structural validation process for us to explore other non-academic outcomes. For example, given its varying characteristics [2], how does self-confidence relate to academic engagement?

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML