-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2014; 4(1): 31-37

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20140401.05

Personality, Preferred Values, Sense of Coherence and Attitude towards Death among Policemen - Antiterrorists

Piotr Próchniak

Pomeranian University, Poland

Correspondence to: Piotr Próchniak, Pomeranian University, Poland.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The present study was aimed at identifying the personality traits, preferred values, sense of coherence and attitude towards death of Polish policemen - antiterrorists. Group of antiterrorists consisted of 44 policemen who represented the special units (Mage = 31.5yr., SD=5.81). Control group consisted of 40 policemen preferred sedentary or routine patrol jobs (Mage=33.3yr., SD=5.10). Subjects were administrated the Zuckerman-Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire – ZKPQ, the Value Survey of Schwartz, the Sense of Coherence Scale and the Death Attitude Questionnaire. It was found that the antiterrorists policemen group scored significantly lower on Neuroticism than the control group and scored significantly higher on Sensation Seeking. The antiterrorists were characterized also with significantly higher result in comparison to the control group in such value scale as: Stimulation. In other scales of values policemen don’t differed. The antiterrorists group scored significantly higher on: the Comprehensibility, the Manageability, Meaningfulness and global Sense of Coherence scales than the control policemen group. Besides, antiterrorists policemen also scored significantly higher on Preferred Fast Kind of Death than the control group. Unexpectedly, anxiety towards death in both groups of policemen was similar.

Keywords: Personality, Values, Sense of coherence, Attitude towards death, Policemen

Cite this paper: Piotr Próchniak, Personality, Preferred Values, Sense of Coherence and Attitude towards Death among Policemen - Antiterrorists, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 31-37. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20140401.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Researchers are looking for subjective traits of people who decide to defend and help others. In this research trend, the researchers are looking for so-called “altruistic personality". Factor analysis of several prosocial personality traits have led to two dimensions of the prosocial personality. The first is abstract, correlating prosocial thoughts and feelings with measures of agreeableness and dispositional empathy. The second is more specific, namely, the self-perception that one is a helpful and competent individual. But these traits are often characteristic for people who help others without the necessity to take high risks too. There is a lack of systematic research of traits of people who are taking high risk in prosocial work. In this article, there will be presented the results of psychological profile of policemen - antiterrorists.The work of antiterrorists is intense, both physically and emotionally. Realization of the occupational tasks in difficult and insecure situations often demands a high level of emotional dedication: chasing criminals, participating in interventions and getting in contact with hostile and aggressive people. As a consequence – job of antiterrorists is potentially very stressful and risky.

1.1. Personality

- The most widely know research on policemen job is work on personality traits[1, 2]. A trait can be defined as a relatively stable characteristic that causes persons to behave in certain ways[3]. Personality researchers proposed a different models of traits. For example, Raymond Cattell developed model of personality based upon sixteen traits. From perspective of this model, Cooper et al.[4] using 16 Personality Factor Questionnaire, found that the British policemen scored higher on traits: A (reserved vs warm), B (concrete vs abstract reasoning), G (expedient vs rule-conscientous) and I (utilitarian vs sensitive) than the normative score in the general population. Hans Eysenck proposed a model of personality based upon just three universal traits: Neuroticism, Extraversion and Psichoticism. From perspective of this model Goma-i-Freixanet and Wismeijer[2] (using Eysenck Personality Questionnaire - EPQ), discovered that Spanish policemen scored lower on Neuroticism and Psychoticism domains than the control group avoiding risk. They also scored lower on the Neuroticism, Psychoticism and Lie Scale than the risk sport group. Using E P Q, Burbeck and Furnham[5] found that accepted police candidate scored higher on Extrovertion and lower on Neuroticism than rejected applicants.Costa and McCrae[6] introduced five basic traits in the so-called Big Five Model: Extraversion, Neuroticism, Conscientiousness, Agreeableness and Openness to Experience. Zuckerman[7] proposed that the Alternative Five Model could be interpreted in terms of biologically determined personality traits. He has suggested that those personality features can not dramatically different from other animals. Based on this consideration, he proposed five personality traits: Neuroticism, Sociability, Aggression/ Hostility, Activity and Impulsive Sensation Seeking[8-9]. In particular, sensation seeking trait may have immediate influence on police work actions. Many research in this area indicate that policemen had higher score on the sensation seeking scale than the control groups[1, 2, 10]. The purpose of the present study is to look for personality characteristics of the antiterrorists, by means of Zuckerman’s the Alternative Five Factor Model[7].

1.2. Values

- Studies of policemen may involve not only personality traits. It seems reasonable to consider what is important to policemen, what values animate their lives. Values describe what is important to human beings[11]. Rokeach[12] treats values as enduring beliefs. Values guide general responses to classes of stimuli[13]. Schwartz[14] defines a value as a transsituational goal that varies in importance as a guiding principle in one's life.The research on values has shown it is associated with the police job[15]. The results of this work are inconclusive. Some studies suggested that policemen preferred job stability and materialistic values[10], family traditions[16], other revealed that policemen preferred excitement involved in the job[17-18].The purpose of the present study is to look for values of antiterrorists manifested in The Schwartz Model[14]. Schwartz Value Survey allows to distinguish the following types of values: Self-Direction; Stimulation; Hedonism; Achievement; Power; Security, Conformity; Tradition; Benevolence; Universalism[14, 19].

1.3. Sense of Coherence

- In the literature of risk taking behavior traits of personality or values are good predictors of motivation of unsafe behavior[9,18]. Not only motivation to risk taking behavior but factors which effective adopting workers to risky situations are very important.We can distinguish two theoretical orientations, which seeks to explain why people stay healthy or ill in risky situations. A “pathogenic” orientation focuses on what makes people ill in danger situation. A "salutogenic" orientation is opposed to a “pathogenic” model[20]. Idea of “salutogenic” orientation was proposed by Aron Antonovsky. The core of this orientation is the focus on successful coping through the selection of realistic coping strategies. From perspective of “salutogenic” model Antonovsky introduced new notion - Sense of Coherence (SOC). The SOC is defined as: “a global orientation that expresses the extent to which one has a pervasive, enduring though dynamic feeling of confidence that (1) the stimuli deriving from one's internal and external environment's in the course of living are structured, predictable and explicable; (2) the resources are available to one to meet the demands posed by stimuli; and (3) these demands are challenges, worthy of investment and engagement”[20]. SOC emerges from generalized resistance resources, which are posited to be major psychosocial resources such as ego strength, social support, cultural stability, wealth, a stable system of values, and beliefs derived from one's philosophy or religion[20]. This concept consists of three themes, comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness.There are not so many studies on the differences of the SOC between professions. Most studies have been made on such groups as: students[21], social workers[22], health care personnel[23]. Relatively less attention was paid to the study of the group of risky occupations. In three studies conducted on Israeli army officer trainees the SOC was very high. The SOC was also found be very high among mountain guides[24].

1.4. Attitude towards Death

- Death is a daily risk of policemen’s job. It is interestingly that we have comparatively little empirical research on the personality of occupational groups, such as policemen, who risk their own life for others. There is some theoretical speculation. Freud[25] suggested that risk taking behavior was a manifestation of an unconscious desire for destruction (thanatos). In theory proposed by Becker[26], (1973), Solomon, Grennberg and Pyszczyński[27] death evokes terror that is diminished by culturally-based meanings that validate the individual’s life. Solomon, Greenberg and Pyszczyński theorize that self-worth, that is that someone is valued member of society, may mitigate this sense of terror. Boyd and Zimbardo[28] suggested that a belief in personal immortality, a life after life, can minimize anxiety. Some people are optimistic and they will be lucky in an extreme situation[29]. People differ in attitude to preferred kinds of death: some humans would like to die faster, without useless reflection, others prefer a slower and more reflective death. So, attitude towards death is multidimensional[30].Research into this current area concentrates on the knowledge of people with personal experience of mortal phenomenon and their attitude towards death, for example terminal patients and physicians.Researchers are mainly interested in people who voluntarily participate in practicing extreme activities (skydivers, climbers) The results of this work are inconclusive. Some studies suggested low death anxiety than a controls[31-32] others revealed such differences[33]. In the working context - Fang-Juan-Liao,[34] found that policemen had score higher on Neutral Acceptance of Death and Death Avoidance, Approach Acceptance was mediocre, Fear of Death was lower, and Escape Acceptance was the lowest. As a whole, policemen accepted the possibility of death, but tended to avoid thinking of death.Police officers aren’t an homogenous group. Some of them are working in financial or administration departments, they prefer rather physical safe job, but others policemen risk their live in daily work, for example policemen – antiterrorists.The purpose of the present study was to analyze policemen-antiterrorists on personality, value system, sense of coherence and attitude towards death. As discussed earlier, findings, there are findings that prove the specific traits of policemen officers. Based on these previous studies I expect for the antiterrorists higher score on Impulsive sensation seeking, Hedonism and Stimulation Values, Openness to change metacategory of value, present time perspective and lower score on Anxiety towards Death than the control group.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- The sample consisted of 44 Polish antiterrorists (only men) (Mage = 31.5yr., SD=5.81). The study of antiterrorists was conducted during the training at the Police School in Slupsk (Poland). The second group was a control group of 40 Polish policemen who preferred sedentary or routine patrol jobs (only men) (Mage=33.3yr., SD=5.10). Policemen from the control group filled in the questionnaires individually at home and returned the questionnaire to the author. Policemen was generally informed about the goals of the research.

2.2. Materials

- Zuckerman - Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire - ZKPQThe Zuckerman-Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire, a tool designed to measure the alternative five-factor model of personality, was translated and adapted into the Polish language. The ZKPQ questionnaire consists of 99 True-False statements[8]. The Polish version has provided satisfactory Cronbach coefficients alpha: Impulsive Sensation Seeking (Cronbach`s α = .72); Neuroticism / Anxiety (Cronbach`s α = .90); Activity (Cronbach`s α = .81); Sociability (Cronbach`s α = .82); Aggression / Hostility (Cronbach`s α = .83). ZKQP also includes an infrequency scale. Infrequency items are used to eliminate subjects with possibly invalid responses (Cronbach`s α = .78). In the Zuckerman's model[7] the impulsivity constitutes one dimension with sensation seeking (Impulsive Sensation Seeking). It would be worth while to treat impulsivity and sensation seeking as independent dimensions to find on what some results of tests put an emphasis[35].Value SurveyThe second questionnaire to be used was the Value Survey containing 57 values[14]. The Value Survey was translated and adapted into the Polish language. Each value was rated on a 9 point scale, ranging from “opposed to my principles” (-1) over “not important” (0) to “of supreme importance” (7). Reliabilities (Cronbach’s alphas) of the value types were as follows: self-direction (Cronbach`s α = .63), stimulation (Cronbach`s α = .67), hedonism (Cronbach`s α = .66), achievement (Cronbach`s α=.70), power (Cronbach`s α=.73), conformity (Cronbach`s α = .57), tradition (Cronbach`s α = .54), security (Cronbach`s α = .61), benevolence (Cronbach`s α=.68), universalism (Cronbach`s α =.76), self-enhancement (Cronbach`s α = .78), openness to change (Cronbach`s α = .74), self-transcendence (Cronbach`s α = .73), conservation (Cronbach`s α = .67).Sense of Coherence Scale Antonovsky's Sense of Coherence Scale is a 29-item, 7-point semantic differential scale translated into Polish[36]. It is composed of an overall scale score and three subscale scores (Comprehensibility, Manageability and Meaningfulness). Each item is presented on a 7 - point Likert scale. The SOC scales include alpha reliabilities between .74 and .91. Death Attitude QuestionnaireThe Attitude Death Questionnaire was constructed by the author of this research. The questionnaire contains 24 items, with four items being utilized per factor. Participants are asked to indicate the extent to which they agree with each of items, using a subscale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The first factor is called “Beliefs in life after death”. (Cronbach`s α = .72). For example, one item that assesses beliefs in life after death is “Life exists after death”. Second factor is called “Contemplation of death”. (Cronbach`s α = .87). One item that exemplifies the contemplation of death items is “I like to listen to consideration about death”. “Fear of death “ is the third factor (Cronbach`s α = .72) (e.g. I feel fear on thought about death). The fourth factor measured by the Attitude toward death Questionnaire is called “Preferred kind of death”(Cronbach`s α = .77). For example, one of the items from the questionnaire assesses preferred kind of death is “I desire to have fast and unexpected death”. The fifth factor is called “Beliefs about controlling death” (Cronbach`s α = .76). For example, one item that assesses beliefs about controlling death is I belief that I can avoid death in extreme dangerous situation. The final factor is called “Paranormal beliefs about death” (Cronbach`s α = .80). (e.g. Horoscopes are able to forecast date of death).

3. Results

3.1. Group Differences

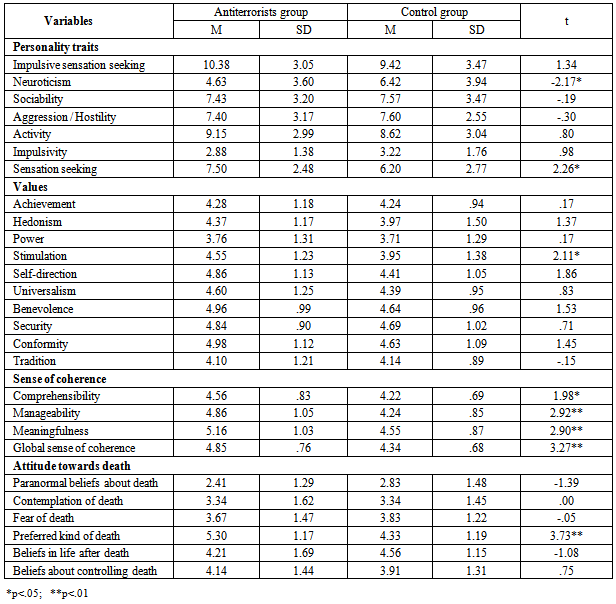

- The groups in this study were compared on each measure using the Student t test. See Table 1.

|

3.2. Multivariate Analysis

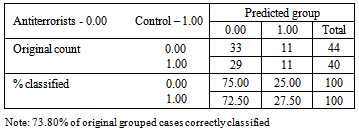

- A discriminant function analysis (DFA) was used to assess the capacity of variables to predict the policemen in the antiterrorists’ and control groups. Variables for the antiterrorists and control group differences were included in the discriminant function analysis. The variables were Neuroticism, Sensation Seeking, Stimulation Value, Global Sense of Coherence and the Preferred fast kind of death. One significant function was identified, and had an eigenvalue of .35 and a canonical correlation of .51, X2 (n= 84) 24.04, p <.001.Table 2 indicate that 73.80% of group cases were correctly classified (75.00% of antiterrorists and 72.50% control group of policemen).

|

|

4. Discusion

- This study explored differences in personality traits, preferred values, sense of coherence and attitude towards death between two distinguished groups of policemen- antiterrorists and policemen preferred sedentary or routine patrol jobs.Although the presented study have not been realized in a cause and effect paradigm, it seems that you can attempt to formulate a more general conclusions of this nature. Personality traits, according to Zuckerman[7], play the role of moderators that have an influence on risk-taking entangled in the possibility of death. The role of these traits is revealed during a professional life, personal life and in the way of spending free time[3].The control policemen obtained higher results in the trait of Neuroticism in comparison with antiterrorists policemen. In this regard, the hypothesis has been confirmed. It means that the antiterrorists are generally more relaxed and stabile than the control group. These results are in accordance with results received by Goma-i-Freixanet and Wismeijer[2].Higher intensity of an Sensation Seeking among the antiterrorists policemen may indicate that they will, during their professional work (but not only), be searching, unknown, and uncertain and even their own health or life is endangered. Extreme situations may be a source of exciting experiences for them. On the one hand, in comparison to the group of control officers, antiterrorists policemen have lower results in such personality traits as Neuroticism and higher result on Sensation Seeking. On the other hand, in comparison to the control group, antiterrorists have higher scores on value Stimulation. The antiterrorists are people who appreciate challenges, seek for experiences and adventures, like a varied living. They can be characterized by positive attitudes towards emotion, especially positive or joyful affect[9]. The current findings are consistent with the results of Meagher and Yentes ([18] or Ragnella and White[15]. In the study of these researchers policemen was motivated in a broad range of thrill-seeking activities.Tests which were carried out aimed at identifying the Sense of Coherence of antiterrorists and control policemen from the perspective of the “salutogenic” orientation proposed by A. Antonovsky. This model assumes successful coping through the selection of realistic coping strategies. In the present research the examined the antiterrorists policemen have obtained higher results in the trait of SOC in comparison with the control policemen. In this regard, the assumed hypothesis has been confirmed. The antiterrorists group scored significantly higher on comprehensibility. For life to be comprehensive and understandable it needs to include a level of predictability. These results mean that antiterrorists policemen validate their surroundings and existence through a system of rational arguments. If something unforeseen happens antiterrorists policemen in risky situations seek an explanation through reason and intelligence. They also tend to believe that good things happen to them for a reason and that pleasant things will continue to them overtime[20]. Antiterrorists policemen group also scored significantly higher on manageability than the control policemen. All individuals have personal recourses and attributes that help them to manage life. In life it is important to have a sense of belonging to other people and a place in a social context. Antiterrorists policemen perceives that resources are at one’s disposal which are adequate to meet demands posed by the stimuli that bombard policemen in risky situations. The control group of policemen have more problem with manage own life.Next – the group of antiterrorists scored significantly higher on meaningfulness. The feeling of meaningfulness is an important part in achieving a sense of coherence. It means that the antiterrorists policemen have to show an emotional involvement and feel strongly about some unsafe situation in their work. In conclusion – the antiterrorists policemen have high the sense of coherence in own life and - in result – they have high score on mental health. Unexpectedly, the antiterrorists had a mean fear of death score and contemplation of death similar to that of the control group, which was contrary to hypotheses. The current findings are not partially consistent with the results of Fang-Juan-Liao,[34]. In his study policemen obtained a lower fear of death. Our results reveal that the antiterrorists, similarly as the control group, fear of own death. This result we can interpret from Terror Management Theory. In this theory - fear of death is universal, for antiterrorists too[27]. The antiterrorists prefer to have fast and unexpected death. They don’t want to have much more time before death to think about own life. It suggests that the antiterrorists aren’t reflective persons. They prefer rather concrete action. Moreover, concentration on death could destroy effective occupational task.

5. Conclusions

- The antiterrorists policemen are people who are thrill seekers, experience low anxiety in dangerous situations and they have high score on mental health. They also prefer fast death without more reflection and have anxiety towards death similar to the others.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML