-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2014; 4(1): 25-30

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20140401.04

Social Aspects as Maintenance Factors of the Obesity Condition: The Somatic Marker Hypothesis

Carla de Meira Leite1, Kátia Rubio2

1Faculty of Education, University of São Paulo (FEUSP), SP, Brazil

2School of Physical Education and Sports, University of São Paulo (EEFEUSP), SP, Brazil

Correspondence to: Kátia Rubio, School of Physical Education and Sports, University of São Paulo (EEFEUSP), SP, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

In contemporary society, the construction of the female identity is associated with beauty, in which thin women represent the desirable standard, dismissing the feeling of belonging and changing the representation of subjectivity in women dissonant of this standard. The aim of this study was to analyze, according to the somatic marker hypothesis, the involvement of social behaviors in the maintenance of obesity and / or weight regain in obese adults. Five women between 25 and 55 years, BMI> 30 kg/m2 were interviewed. The methodology used was the life story, because we believe that, in the report of personal story, significant episodes reflect the individual and collective imagination. The data collected indicate the presence of hegemonic social discourse in relation to female corporeality as maintaining factor of the obesity condition, suggesting the need to investigate the consequences of the naturalization of discourse, such as formation of stigma and the representations of professionals who work with this population, in order to reflect on intervention strategies that take into consideration the somatic marker hypothesis.

Keywords: Obesity, Somatic Marker, Society, Behavior, Health Professionals

Cite this paper: Carla de Meira Leite, Kátia Rubio, Social Aspects as Maintenance Factors of the Obesity Condition: The Somatic Marker Hypothesis, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 25-30. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20140401.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In recent decades, the topic of obesity is mandatory in scientific events dealing with health, since there is a range of comorbidities associated with obesity, which makes the various medical specialties to debate this situation. Based on its multifactorial characteristic, interventions from other areas such as nutrition, psychology and physical education have been recognized as important in the treatment of this condition, considered by the Ministry of Health of Brazil as a risk factor.In Brazil, besides the impossibility of offering a multidisciplinary treatment via public health system, the spaces for the practice of leisure are increasingly reduced and the practice of physical exercises is limited to fitness centers, since physical education performed in school is aimed only at changes in body composition. This means that there is no policy for obesity control, diagnosis and intervention, except for bariatric surgeries performed by the Unified Health System (SUS), which, while necessary in some cases, show the absence of a prevention policy.However, one cannot assume that the access to treatment ensures the definitive reversal of obesity, since success of interventions is frequently observed but not in maintaining weight loss. According to Vieira et al[1], it is estimated that only twenty percent of patients participating in weight loss program are successful in maintaining weight in the long term.There are no empirical studies in literature associating the somatic marker hypothesis with maintenance of the obesity condition; however, studies by Franko, Debra L., et al[2]; Compher C. W[3]; Wooley, Orland W., Susan C. Wooley, and Sue R. Dyrenforth[4] Swami, Viren, et al.[5] on dissatisfaction, to a greater or lesser degree, of women of all races and continents with their body image related to overweight, suggest more than the finding of this dissatisfaction.There may be some exaggeration in this type of consideration about the discrimination faced by obese women; however, the press frequently reports episodes related to the topic such as research at Yale University in which 5% of respondents would rather lose an arm and 4% would rather become blind than being fat. Or the case of a 10-year-old girl that called the attention of teachers with the habit of spitting incessantly, fearing of becoming fat with saliva.[6]Thus, the research on the possible factors linked to the maintenance of the obesity condition is as pertinent as researching the predisposing factors. The assumption of the participation of social aspects in the predisposition or maintenance of the obesity condition is supported on the etiology presented by Dâmaso[7], in which endogenous factors represent less than 5% of obesity cases, compared with 95% coming of exogenous factors (behavioral). In this paper, the effect of the somatic marker on these behavioral factors will be discussed.

2. The Somatic Marker Hypothesis

- In every age, models and explanatory paradigms are created for the phenomena and / or objects of knowledge, which production promotes contributions / disruptions and displacements of body representation and subjectivity. Due to neurological plasticity (increased by the rate of changes of the post-modern world) and the new worldviews offered by the production and circulation of knowledge, contemporary man processes information in a more complex way compared to modern or medieval man.Pimentel and Bruno[8] identify a shift of sense production towards information management, as an implication of the contributions of neuroscience and biotechnology over thought and consequently on the subjectivity of contemporary man.For these authors, contemporary man initiates a shift from interpretive thinking, aware of an inner truth to be unveiled therefore polysemic, to a thought that manages information so that the subject can adapt to future configurations. Genetic predisposition tests and the somatic marker hypothesis subsidize the discussion about the implications of the comparison between organism and information systems on the function of thought.Damasio[9] advocates the body rooting of subjectivity, suggesting an emotionalization theory of mind. In it, we question both the mind / body dualism, as the separation between pure reason and emotions in decision making. This informational body determines interdependence between emotion (anchored in corporeality) and mind in order to obtain effective cognition.The somatic marker, from a positive or negative bodily perceived experience, generates a mental picture from which a feeling that will influence decision making emerges. Damasio[9] considers that a wise decision brings results in the personal field, such as physical and mental health, sense of belonging to a social group, financial stability, etc.In the hypothesis defended by Damasio, images show in almost simultaneous schemes; however, before consideration of advantages and disadvantages, or of envisioning a solution through reasoning, a trigger is fired. When obtaining a bad outcome as a result of an inadequate option, there is a bad visceral feeling that "marks" this image, which was the reason Damasio named it as somatic marker.Thus, in addition to warning us about the decisions, the somatic marker serves to reduce the range of options that the images bring us, contributing to the reasoning process, which is subsequent to it. The process is repeated with a positive somatic marker, creating an incentive for that image, i.e., it increases the accuracy and efficiency of the decision process and in the lack of it, both are reduced.It is worth mentioning that the somatic marker can emerge from experience or its simulation, i.e., the brain can reproduce an image, simulating an emotional state without having to reconstruct it in the body.This process called "as if" or "contour" mechanism, reinforces the fact that bodily sensations and feelings occur at the same time, otherwise, it would be necessary to repeat the experience to recover the somatic printing. The images depicted in the body, through sensations, are constantly updated. Thus, the feelings translate the bodily state in which we find ourselves and create an image that will be juxtaposed with the image of other external objects and situations, thus creating a representation that will assign a meaning of pain or pleasure[9].However, this efficient and responsive system in running away actions or predation, does not preserve us from harmful choices such as smoking or overeating. Considering the process of losing weight in obese women, it is a fact that although the obesity condition represents an important distress factor, causing a negative energy balance in order to reverse the obesity process is always a task that demands great effort, relapses and frustration.It seems that the compensation system is more effective in the actions of immediate reward. The prompt and tangible satisfaction that food gives to these women outweighs the clear and late satisfaction they would have losing weight in the medium to long-term. Which factors would be involved in the mechanism that leads these women to succumb to excessive caloric intake ignoring the consequences that bring them so much distress?In the somatic marker hypothesis, Damasio[9] reported the need for a positive feeling (from a positive sensation) so that people can withstand periods of deprivation for the purpose of future results. According to social behavior in relation to female somatic image, it is inferred that in modern times, an obese or overweight women hardly experiences any positive marker relative to her image. This author corroborates our hypothesis when discussing the role of culture in this process:[ ... ] The somatic markers are thus acquired through experience, under the control of an internal system of preferences and under the influence of an external set of circumstances that include not only entities and phenomena with which the body has to interact, but also social conventions and ethical rules (p. 211)[9].Similarly, Matos[10] argues that the eating attitude is a product of learning, where the behavior is reinforced from the consequences it produces. For this author, food can be a substitute gratification, equivalent to affection, and food restriction could mean abandonment, rejection or punishment. In addition, the author suggests that inadequate eating behavior is a clear symptom of latent psychopathology, where overeating may represent a defense mechanism to cope with a personal inadequacy, or a mechanism to attenuate distress, recurrent feeling in stigmatization victims.

3. Formation of Stigma

- In this reappropriation of body by models, the symbolic and libidinal order is disrupted, what Baudrillard[11] termed "synthesis" narcissism, i.e., the integration of ego by speculate recognition and the look of the other, and homogenized body deconstructed as Eros and indexed to collective models .Supported on the belief that the beauty standard is a matter of choice, society reserves the right to fill the daily lives of these women with observations that reflect this conception. According to Goffman[12], when social relationships are established, which is normal for us, in comparison with others, we categorized by its attributes, to which social identity it belongs.Elias[13] argues that the weakening of moral self-image of a less structured group is through the denial of its virtues and the strengthening of those of the strongest group, i.e., the established identities, protecting the lifestyle and the current standards. This practice is successful as the speeches are incorporated, or when negative features are recognized and indicated by the established identities in some people from the discriminated group.In addition, in the issue of standardization of female bodies, for example, there is a great merchandising enhancement from the dietary food sector that in Brazil grew 420.47% from 1993 to 1998, up to the unexpected title of world champion in aesthetic surgeries.[14]The effects of homogenization of discourse are present even in spaces that should favor the otherness. The study by Höglund&Normen[15] found that Physical Education teachers, qualified professionals to contribute to the reversal of the obesity condition are a risk group for eating disorders. Among PE teachers interviewed in a fitness center in Sweden, 35% reported having some eating disorder and for 55% of them, life revolves around physical activity and among those with normal weight, 76% declared to be overweight.In this hegemonic stigmatization produced and spread by various social sectors, even by medicine, since society tends to incorporate medical discourse as dogmas in which medicine provided to medicalize beauty, the confrontation between the socially determined body standard and the perceptions of our respondents reinforces the negative somatic markers, leading to episodes of compensatory hyperphagia.

4. Objective

- To discuss the role of social configuration, which is stigmatizing for the obese woman in maintaining behaviors that prevent the reversal of the obesity condition, from the somatic marker hypothesis.

5. Method

- The method used in this study was the life stories of participants, according to Bosi[16] Cruikshank[17], Ferraroti [18], Meyer[19] Poirier, Valladon, Raybaut[20] Rubio[21] [22], based on narratives collected from the five women. These narratives provided information necessary to illustrate the somatic marker hypothesis as Damasio[9].

6. Life Story

- The methodology chosen to access this symbolic universe was the life story. The intention was to find a trace, an image, a feeling, a break, a meaning common to these women that would show the relationship between social behavior and the formation of somatic markers.Considering the importance of culture and subjectivity in forming mental images, this qualitative methodology fits the research proposals intended, since on the one hand, it focuses on the perspective of the actor's action, considering that understanding a behavior is only possible from the protagonist’s point of view. On the other, it captures the values of the culture in which the subject is inserted, since the observations made by the subject on the reality outside him are a reflection and projection of the experienced reality. [21]The life story allows the narrator the re-visitation and reinterpretation of significant moments, obeying the chronology not of logos but of affection. Chauí[23] supports this idea by stating that, the act of describing the substance of social memory, which is the way to remember, is both social and individual. Bosi[16] warns for the fact that recounting is an act of subjective creation of the narrator; the affective logic chosen to order the facts is unknown to the researcher. Hence, it is important for the researcher to police his representations and stereotypes, not to make ideological inferences or fill in the narrator’s gaps in order not to undermine the narrative. Such considerations become even more relevant, since the theme is rich in stereotypes and the narrative of these women was associated with body representations that referred them to distress experiences. For Berger[24], the body is a product and privileged locus of reflection and production of culture; therefore, it is expected that interviews lead to such an exposition that we believe will expose the symbolic marks carved by culture.

7. Sample

- Five adult Caucasians women with the following characteristics were interviewed:Five adult women who met the following criteria for participation in the project were interviewed:• To be a woman• To be over 25 and under 55 years of age• BMI greater than 30 kg/m2• To have undergone at some point in life treatment with the goal of losing weight

|

8. Data Collection

- Before the interview itself, there was a pre-interview, where the respondents were weighed and measured to calculate the BMI and informed over the content and use of survey data in order to avoid any constraints, later or even during the interview. Interviews were individually, with mean duration of two hours, conducted and recorded on portable camera.

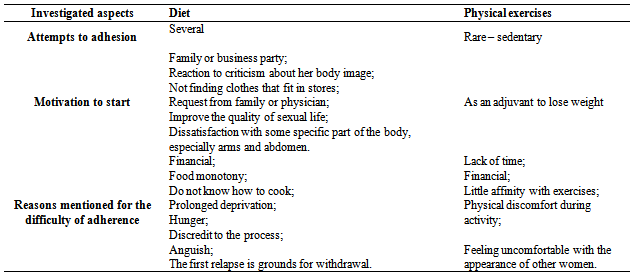

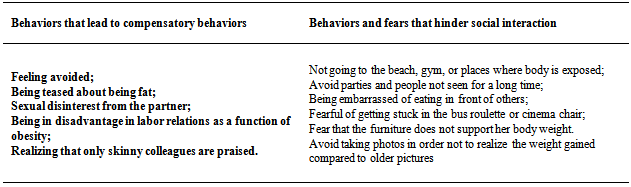

9. Results

- In Brazil, despite the favorable climate, there are few public spaces for the practice of systematized exercises, and the only option for the population is the search for clubs and private gyms for the practice of exercises. With the advent of bodybuilding and ostentation of the female body, it is observed in academies a greater demand for aesthetic purposes than the acquisition of health and wellness (ZORZAN AND WOUNDS)[26].The bodies of these users contrast with those of our sample, making the place hostile due to the implied criticism in the eyes of others. This sensation produces three undesirable effects: withdrawal from physical exercises, hyperphagia as compensation and abandonment of food control as a function of relapse, perpetuating the behavior that keeps the obesity condition, as reported by one of the interviewees"It keeps me away from the fitness center, I get mad at myself for letting the criticism of others affect me, and I think: if I was lean, this disapproval look would not occur. These looks make me think a lot of nasty things and it annoys me to think that my body triggers that look. So I eat more and more and then ... I get depressed" (p. 116)[27]The life stories of the women interviewed offered evidence of how they reached the obesity condition. Based on this fact, the relationship between the aspects of these women's lives and factors that could reverse this condition, such as diet and exercises was investigated. Furthermore, what kind of recurrent behavior on their somatic image evoked compensatory behaviors of food intake and / or those that brought harm to social life was also investigated as tables below:

|

|

10. Concluding Remarks

- By highlighting the relationship of social aspects with the somatic marker in maintaining the obesity condition, one intends to expand the analysis, emphasizing more the connections that are established with the experience than the structures under which this phenomenon develops, for example psychoanalysis and language, so that, in addition to the structuring points, deadlocks, hesitations and negotiations between the generation of anguish and possibility to placate it are also considered.Having the somatic marker as a maintenance factor of this undesirable condition suggests the search for the identification of the episode that started the first distress and later the reflection on the feeling that triggers compensatory behavior is the reinforced contour mechanism. Taking a picture and realizing that she became fat may not have the same weight of being sexually rejected by the object of desire.If two such distinct episodes are triggering the same behavior, the challenge is to create strategies that dissociate the new event from the contour mechanism. In this sense, it is necessary to consider the impact of social aspects (at least those tributaries of sociopathological conditions) and corporeality in the constitution of subjectivity for a proposition of more effective methods and theoretical frameworks in the treatment of obesity.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML

ISSN 0104-657.

ISSN 0104-657.