-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2013; 3(6): 161-168

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20130306.03

Emotional Reactivity: Critical Analysis and Proposal of a New Scale

Rodrigo Becerra 1, 2, Guillermo Campitelli 1

1School of Psychology and Social Science, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, WA 6027, Australia

2Freemantle Hospital, WA, Australia

Correspondence to: Rodrigo Becerra , School of Psychology and Social Science, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, WA 6027, Australia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The goal of this article is to provide a review of the literature on conceptual aspects and measurement of emotional reactivity, and to propose a new measurement of emotional reactivity that addresses the problems identified in the review. We discussed the Behavioral Inhibition/Behavioral Activation (BIS/BAS) scale, the Early Adolescence Temperament Questionnaire (EATQ), the Affect Intensity Measure (AIM), the Emotion Intensity Scale (EIS), and the Emotional Reactivity Scale (ERS). Our review concluded that most of the scales are either too broad (BIS/BAS, EATQ), or too narrow (EIS, AIM). Moreover, ERS, which does not suffer from this problem, does not include valence and it was mainly validated with adolescents. We therefore introduced a new scale–the Perth Emotional Reactivity Scale (PERS)–which overcomes the identified problems. PERS is guided by the tripartite model of emotional reactivity (activation, intensity and duration) and it also includes valence (positive and negative emotions). It contains 5 positive valence items and 5 negative valence items in each dimension. Thus, it contains 30 items. Moreover, PERS includes three non-scorable items to measure subjective report of physiological changes. We conclude that PERS might prove to be a useful tool to assess emotional reactivity more precisely.

Keywords: Emotional reactivity, Emotional regulation, Scale, Emotional response, Theoretical study

Cite this paper: Rodrigo Becerra , Guillermo Campitelli , Emotional Reactivity: Critical Analysis and Proposal of a New Scale, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 3 No. 6, 2013, pp. 161-168. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20130306.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The present paper introduces a new scale that aims to assess emotional reactivity. Emotional reactivity is normally conceptualized as a component of emotion regulation. Several authors consider that the construct emotional regulation has the potential of unifying diverse symptom presentations and maladaptive behaviors (e.g.[1],[2],[3]). Linehan[4] has offered the most comprehensive work incorporating emotional regulation in a clinical disorder. Linehan and colleagues postulated that emotional dysregulation (i.e., failure of emotional regulation) constitutes the main etiological factor and the crucial point of intervention for borderline personality disorder (see[5],[6], [7]). More recently, emotional dysregulation was also incorporated in models of bipolar disorders and major depression disorder (see[8],[9],[10]). Moreover, many of the diagnostic criteria of the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV,[11]) include disturbances in regulatory processes[12].Emotion regulation involves any extrinsic and intrinsic processes aimed at monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions; especially their intensive and temporal features, to bring about one’s goals[13], and includes both voluntary regulatory processes and automatic processes[14]. The voluntary aspects of emotional regulation (e.g., awareness and understanding of emotions, regulation strategies, control of impulses) have received much more attention (e.g.,[15]) than the characteristics of the emotional response (i.e., emotional reactivity)[16]. This is unfortunate because the emotional reactivity is one of the starting points of the emotional experience and appears to be causally related to the ability to regulate emotions after an emotional experience has unfolded[17].The goal of this article is to provide a review of the literature on conceptual aspects and measurement of emotional reactivity, and to propose a new measurement of emotional reactivity that addresses the problems identified in the review. This article continues as follows: first, we review the conceptual aspects of emotional reactivity and its relationship with clinical disorders; then we review the scales of emotional reactivity or similar constructs; finally, we propose a new scale–the Perth Emotional Reactivity Scale, PERS.

2. Conceptual Issues of Emotional Reactivity and Its Relationship with Clinical Disorders

- Emotional reactivity can be seen as a set of brief pro-survival states that prepare humans (and other species) for actions[18], they allow them to discriminate between good and bad stimuli[15], and they tend to give rise to behavioral responses relevant to the stimuli. Emotional responses differ from moods, which are more diffuse and tend to bias cognition ([19],[20]). Additionally, emotional reactivity appears to be a multifaceted phenomenon, which leads to changes in the area of subjective experience, behavior, and central and peripheral physiology[21]. The similarities and differences between emotional reactions, moods and other related concepts are not clearly demarcated and authors have provided different classifications. To circumvent this problem in this review, we explicitly adopt Scherer’s approach[22]–later refined by Gross[15]– which conceptualizes affect as an umbrella concept under which affect-related phenomena are subordinated (see Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Emotion and associated affective terms |

3. Scales of Emotional Reactivity or Similar Constructs

- Despite the importance of emotional reactivity in psychopathology, there are several problems underlying its assessment. In order to organize the review we follow Davidson’s classification of the components of emotional reactivity: (a) valence, (b) activation, (c) intensity and (d) duration[20]. Clinically, these components appear to have been useful for conceptualizing the salient emotional difficulties in borderline personality disorder (see[4]). Activation refers to how quickly people respond; intensity to how intensely the experience is felt, and duration to how long it takes to the person to return to baseline (pre-stimulus presentation). The biosocial model proposes that these three components are impaired or weak in BPD. As a result of some inconsistencies in research findings, the model has been further refined and the role of type of stimuli has been investigated. For example, the Affective Picture System (IAPS,[38]) was utilised to test whether people with BPD differentially reacted to positively or negatively valenced stimuli[39]. It was found that those with BPD showed significantly greater physiological reactivity when viewing unpleasant slides, suggesting that in BPD the level of reactivity is dependent on the emotional valence of the information being processed. Comparable findings have been reported by others (e.g.,[40],[41],[42]) and in different diagnoses (e.g.,[39]) We posit, therefore, that for a scale to be clinically useful, the valence dimension of the emotional experience should be included.Unfortunately there has been almost no single dedicated measure to assess emotional reactivity in the literature; therefore, the replication of studies of this nature is scarce. We now describe some of the measures of emotional reactivity, and we indicate the problems that these measures have.Carver and White[43] are credited with one of the first efforts in creating a scale that assessed emotional reactivity. They designed the Behavioral Inhibition/Behavioral Activation (BIS/BAS) scale, which assesses a broader construct involving a behavioral approach system (BAS) (responses that regulate appetitive motives) and a behavioral avoidance (or inhibition) system (BIS) which regulates aversive motives. These mechanisms are postulated to be activated by physiological systems and neuroanatomical regions of the brain. The BIS inhibits behaviors that might lead to negative or painful outcomes, and thus it is responsible for feelings like fear, anxiety, frustration, sadness, etc., whereas the BAS is sensitive to reward, causes the person to begin movement towards goals and it is responsible for positive feelings. The scale has a pool of items that reflect either BAS or BIS sensitivity, and are presented in a 4-point Likert-type format with 1 indicating strong agreement and 4 indicating strong disagreement (with no neutral response). To assess BIS the scale uses statements that reflect a concern over the possibility of a bad occurrence ("I worry about making mistakes"), whereas the assessment of BAS sensitivity used statements that reflect: “one of the following: strong pursuit of appetitive goals ("I go out of my way to get things I want"), responsiveness to reward ("When I get something I want I feel excited and energized"), a tendency to seek out new potentially rewarding experiences ("I'm always willing to try something new if I think it will be fun"), or a tendency to act quickly in pursuit of desired goals ("I often act on the spur of the moment")”[43] (p. 322). This scale was created against a broader conceptual model (see[44],[45]) that postulates the two dimensions of personality explained above. Given that the BIS/BAS items are broad (e.g., “When I get something I want, I feel excited and energized”), and are closely related to personality features, rather than emotional reaction, it is problematic to use this scale as a measure of pure emotional reactivity. The Early Adolescence Temperament Questionnaire (EATQ;[46]) taps on emotional reactivity but assesses, like the BIS/BAS scale, broader constructs: temperament and social emotional functioning. The aim of the scale is to assess temperament in the early adolescent period including three postulated central components of human personality, namely, arousal, emotion and self regulation. Interestingly, literature on emotion tends to include arousal within the emotional construct but the authors of the EAQT separate them. EAQT assesses arousal via measuring internal and external sensitivity to low intensity stimulation and symptoms and behaviors related to somatic arousal. EAQT includes four scales measuring negative emotions (fear, irritability, shyness, and sadness) and two scales measuring positive emotions (high intensity pleasure and low intensity pleasure). The advantage of this scale is that it includes both negative and positive emotions, but the scale is over-inclusive as it includes the assessment of self-regulation, which more contemporary commentators in the filed characterize it as a much more complex construct, that includes multifaceted phenomena (e.g.,[15]). Thus the scale might obscure the analysis of emotional reactivity in its simplest form. Another problem of EAQT is that it was designed to measure adolescents, thus it is not clear whether it would be useful to assess emotional reactivity in adults. Other measures have assessed more specific aspects of emotional reactivity. For example, the self-report Affect Intensity Measure (AIM;[47]) is used to index trait levels of affect intensity. Affect intensity was defined by the authors as stable individual differences in the strength with which individuals experience their emotions, irrespective of their valence. The authors observed that there are stable individual differences in the typical intensity experienced by people facing emotional stimuli. Some people would experience their emotions only mildly and with only minor fluctuations, and others would experience their emotions quite strongly and with an intense reactivity. The scale is a 40-item questionnaire that assesses the characteristic magnitude or intensity with which an individual experiences his or her emotions. If intensity were the only component of the emotional reactivity this scale would be very useful. However, from a clinical point of view, the duration and activation of the emotional experience are important components, as they have been postulated to play a crucial role in emotion dysregulation (e.g.,[15]). Furthermore, Larsen and Diener firmly adhere to the notion that affect intensity applies identically across different valenced stimuli, that is, individuals who experience positive emotions more strongly, will similarly experience their negative emotions more strongly. They based this observation on studies using normal population in which correlations between positive affect intensity and negative affect intensity was found to be high (ranging from .70 to .77)[48]. Their findings could be applicable to the general population but this appears problematic to replicate in clinical populations (e.g.,[4]). This well-constructed test appears both somewhat too specific and utilizes only one type of emotions, making it less useful to test clinical populations.Another specific measure of intensity is the Emotion Intensity Scale (EIS,[49]). This measure focuses on intensity alone but adds the dimension of valence, that is, it assesses emotional intensity of positive and negative emotional states, unconfounded by the frequency with which those states are experienced. In the EIS respondents endorse one of five choices for each of 30 items. The scales assess the usual, or typical, intensity of the described emotion when that emotion is experienced. An earlier version of the EIS[50] contained items which the current version dropped because they were weakly correlated with the total score (r < .30). The EIS has 12 items that ask about emotional responses to relatively detailed scenarios and 18 items specify an emotion without providing substantive contextual information. The total EIS score can range from a minimum of 30 to a maximum of 150, and it generates subtest scores for positive and negative emotions. As with the AIM, the EIS focuses exclusively on intensity of emotions and although it is an improvement from earlier scales, the exclusion of reactivity and duration makes it a less convenient scale for the assessment of more comprehensive assessment of emotional reactivity. A more recent measure is the Emotional Reactivity Scale (ERS,[16]). The ERS was created in response to the lack of specificity of previous measures (e.g., BIS/BAS, EATQ) or the narrow focus of the investigations when studying emotion reactivity (e.g., AIM, EIS). The ERS is a 21-item self-reporting measure designed to assess three aspects of emotion reactivity: sensitivity (8 items; e.g., “I tend to get emotional very easily”), arousal/intensity (10 items; e.g., “When I experience emotions, I feel them very strongly / intensely”), and persistence (3 items; e.g., “When I am angry/upset, it takes me much longer than most people to calm down”). Each item is rated on a 0 to 4 scale (0=not at all like me, 4=completely like me), with total possible scores ranging from 0 to 84. The ERS factors correspond to Linehan’s dimensions, namely activation, intensity and duration[4]. It was found that adolescents with a mood, anxiety, or eating disorder reported significantly higher emotion reactivity than controls or those with substance abuse problems, suggesting that emotional reactivity is associated with specific forms of psychological disorders [16]. The authors reported that their confirmatory factor analysis yielded only one factor, and that the measure showed good internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .94). Additionally, the Sensitivity, Arousal/Intensity, and Persistence subscales demonstrated strong internal consistency, suggesting that the total ERS score, as well as the individual subscales, are reliable indicators of emotion reactivity. The construct and divergent validity were also examined and the ERS showed good correlations with compatible and unlike constructs respectively. Although the ERS seems to have significantly improved the assessment of emotional reactivity, it is still problematic in that it does not consider valence, with all items having a negative valence (e.g., “I often feel extremely anxious”; “I am often bothered by things that other”; “I am easily agitated”). Given the reactivity to emotional stimuli might depend on valence (e.g., as reported in Borderline Personality Disorder), we believe that the sign of the emotion might have a differential effect, particularly if we were to use this measure in the psychopathology domain. Another problem of ERS is that it was only validated with adolescents, thus it is uncertain whether it would be a good scale to measure emotional reactivity in adults.It appears therefore that there is a gap in the literature of assessment of emotional reactivity. Most scales are either too broad (BIS/BAS, EATQ), or on only one component of emotional reactivity (EIS, AIM). A more recent development proposes a scale (ERS) that improves the assessment of emotional reactivity; however this scale does not include valence and was mainly validated with adolescents. Given this background, we felt that it was necessary to create a new scale.

4. Perth Emotional Reactivity Scale (PERS)

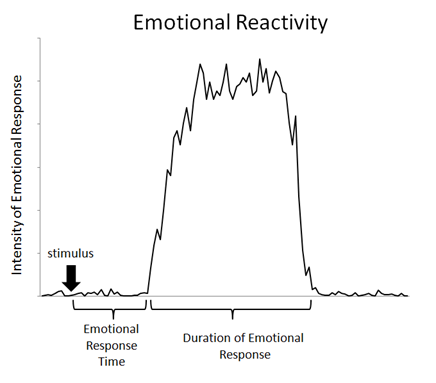

- We present in this article a new emotional reactivity scale that improves upon previous efforts by including three dimensions of emotional reactivity (activation, intensity and duration; (see Figure 2 for a graphical representation of these dimensions), incorporating valence (using negatively and positively phrased questions), and aiming to assess emotional reactivity in adults.

| Figure 2. A representation of the three components of emotional reactivity: activation (represented by the emotional response time), intensity and duration |

4.1. Questions in the Activation Dimension

- There are 10 questions to assess activation of the emotional reaction. To convey the notion of activation we included terms like very quickly; in an instant; and automatically. Five questions measure positive valence and the other five questions measure negative valence.

4.1.1. Activation: Positive Valence

- To convey the positive valence we included notions and terms like: happy, positive, enthusiastic, good news:1. I tend to get happy very easily2. My emotions go automatically from neutral to positive 3. I tend to get enthusiastic about things very quickly4. I feel good about positive things in an instant 5. I react to good news very quickly

4.1.2. Activation: Negative Valence

- To convey the negative valence, we included notions and terms like: upset, disappointed, frustrated, and negative:1. I tend to get upset very easily2. I tend to get disappointed very easily3. I tend to get frustrated very easily4. My emotions go from neutral to negative very quickly5. I tend to get pessimistic about negative things very quickly

4.2. Questions in the Duration Dimension

- Another set of 10 questions are directed to the duration of the emotional experience. There are five questions that ask for the duration of positive emotions, and five questions for the negative emotions. To convey the duration aspect we included notions and terms like: for a while, good part of the day, quite a while, long time.

4.2.1. Duration: Positive Valence

- To convey the positive valence within the item, we included notions and terms like: happy, feeling positive, enthusiastic, pleasant news, paying compliments:1. When I’m happy, the feeling stay with me for quite a while 2. When I’m feeling positive, I can stay like that for good part of the day3. I can remain enthusiastic for quite a while4. I stay happy for a while if I receive pleasant news5. If someone pays me a compliment, it improves my mood for a long time.

4.2.2. Duration: Negative Valence

- To convey the negative valence we included notions and terms like: upset, anger, frustration, negative mood, and annoyed: 1. When I’m upset, it takes me quite a while to snap out of it2. It takes me longer than other people to get over an anger episode 3. It’s hard for me to recover from frustration4. Once in a negative mood, it’s hard to snap out of it.5. When annoyed about something, it ruins my entire day

4.3. Questions in the Intensity Dimension

- Intensity is also investigated with 10 items, 5 with positive valence and 5 with negative valence. To convey intensity we included notions and terms like “more intensely than others”; “very deeply”; “very strongly”; “very powerfully”; “more deeply than others”.

4.3.1. Intensity: Positive Valence

- To convey the positive valence within the item, we included notions and terms like: happiness, joyful, positive moods:1. I think I experience happiness more intensely than my friends2. When I’m joyful, I tend to feel it very deeply3. I experience positive moods very strongly4. When I’m enthusiastic about something I feel it very powerfully5. I experience positive feelings more deeply than my relatives and friends

4.3.2. Intensity: Negative Valence

- To convey negative emotions we included notions and terms like: upset, frustration, unhappy: 1. If I’m upset, I feel it more intensely than everyone else2. I experience the feeling of frustration very deeply3. Normally, when I’m unhappy I feel it very strongly4. When I’m angry I feel it very powerfully5. My negative feelings feel very intensely

4.4. Awareness of Physiological Changes (Not Included in the Scoring)

- We included threes questions about physiological changes, which would be useful for investigating correlations between this scale and physiological measures:1. When I’m upset my body feels different2. I feel my emotions in my body 3. I can’t tell I’m emotional because I feel it in my body

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- This paper introduced a new scale called the Perth Emotional Reactivity Scale (PERS). Emotional reactivity is an important component of a broader phenomenon termed Emotion Regulation which refers to processes aimed at monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions [13]. Emotion regulation has acquired a more significant role in psychopathology with ample evidence showing its centrality in Borderline Personality Disorder ([5],[6],[7]), and also in bipolar disorders and major depression disorder (see[8],[9]). A relatively neglected aspect of emotion regulation is emotional reactivity which we conceptualize, consistent with previous research ([4],[20]), as a process that includes three dimensions, namely emotional response, intensity and duration. Scrutiny of the literature in assessment of this phenomenon, reveals that there are a few extant scales. However, we estimate that these scales tend to either omit or over include, rendering them less precise in the assessment of emotional reactivity in adults from the normal population and/or adults with psychiatric diagnoses. Against this background we proposed the Perth Emotional Reactivity Scale (PERS) which is guided by the tripartite model of emotional reactivity (activation, intensity and duration) and it also includes valence (positive and negative emotions). Differential responses to differently valenced emotional stimuli have been reported in the psychopathology literature (e.g.,[39],[41]). The PERS consists of 30 questions in addition to 3 questions (non-scorable) that ask about awareness of physiological changes whilst experiencing an emotion. We believe that the PERS will contribute to a more accurate assessment of emotional reactivity. Many psychopathologies are characterized by an overly reactive emotional response but the precise nature of this response has not been well established. For example, do all psychopathologies react differently to emotional situations in terms of the speed of the reaction? Do some diagnostic groups experience this emotion more intensely? Do all presentations tend to react for longer periods of time as compared to the normal population? The answers to these questions will inform the interventions when they try to assist patients with their proven weaknesses in emotion regulation. However, we need to have more specific measures targeted to psychiatric adult populations that will characterize the emotional reactivity profile in this population. The next stage in validating this measure will be to administer it to different diagnostic groups and compare their total scores plus the three sub-components to a matched normal sample. PERS could also be used as an added subjective dimension of emotional reactivity in psychophysiological studies. The congruity or discrepancy between self-reporting and objective psychophysiological emotional reactivity is an area that could also inform the broader construct of emotion regulation (see[51]). In summary, we believe that the PERS has the potential to aid the psychological therapy of psychiatric presentations by assisting in disambiguating between reaction, intensity, and duration of the emotional reactivity and by clearly determining if these dimensions are influenced by valence.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML