-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2013; 3(4): 114-119

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20130304.04

Workplace Violence and the Cost-Benefit Trade off of Zero-Tolerance Safety Policies in Central Nigerian Hospitals

Wurim Ben Pam

Plateau State University, Bokkos, Jos - Nigeria

Correspondence to: Wurim Ben Pam, Plateau State University, Bokkos, Jos - Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

A well written and implemented Workplace violence prevention program, combined with engineering controls, administrative controls and training can reduce workplace violence and the attendant costs in both private and public organisations. The major objective of this paper is to unravel and analyze the cost-benefit trade off of implementing zero-tolerance policies and to investigate the potency of such policies in the reduction of workplace violence. Data was collected from a convenient sampling of 103 employees of 4 hospitals and clinics and analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test statistic. The result showed that early identification of certain risk factors significantly impact violence prevention and protection; zero-tolerance safety policies do not reduce workplace violence and costs; and the costs of implementing zero- tolerance safety policies are greater than the benefits of implementation. The paper recommends that employers should provide safety education for employees, secure the workplace, provide drop safes to limit the amount of cash on hand, instruct employees not to enter any location where they feel unsafe and equip field staff with cellular and hand-held alarms or noise devices.

Keywords: Workplace, Violence, Cost-Benefit Trade off, Zero-Tolerance, Safety Policies, Central Nigeria, Hospitals, Prevention, Risk Factors, Safety Education

Cite this paper: Wurim Ben Pam, Workplace Violence and the Cost-Benefit Trade off of Zero-Tolerance Safety Policies in Central Nigerian Hospitals, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 3 No. 4, 2013, pp. 114-119. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20130304.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Workplace violence is a far more common feature in organisations than previously thought. While about a million Britons may have experienced physical aggression in the workplace in the past two years, nearly 2 million American workers are victims of workplace violence each year.Unfortunately many more cases go unreported[1]. The situation is not any different in developing countries of Africa, Asia and Latin America.Workplace violence can strike anywhere, anytime and no one is immuned. It ranges from threats and verbal abuse to physical assaults and even homicide. It can affect and involve employees, clients, customers and visitors.Homicide is currently the fourth-leading cause of fatal injuries in United States. According to the Bureau for Labor Statistics Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI), of the 4,537 fatal workplace violence that occurred in the United State in 2010, 506 were workplace homicides. Homicide is theleading cause of death in the workplace. Workplace violence can be inflicted by an abusive employee, a manager, supervisor, co-worker, customer or family member.What can managers and employers do to protectemployees, clients, customers and visitors of the organisation? Managers are faced with tough policy issues in the area of workplace violence and prevention. The Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) and other governmental legislations and obligations further make it mandatory for organisations to draw and implement violence protection and prevention policies. Under such laws, each employer has a “general duty” to provide a place of employment free from recognized hazards (violence) and to comply with all standards of safety and health established in the law. As a result, manyorganisations have applied isolated employee strategies ranging from risk assessment of violence to employee counseling, and Employee Assistance Programs (EAP)[2][3].What has come out of these isolated strategies of prevention and protection? In spite of the aforementioned, about 16 U.S workers die on the job each day[4] and more than 5.7 million workers (roughly 6.3 of every 100) get sick … every year because of their jobs. Of these, 1.8 million workers have ergonomics-related injuries, such as Repetitive – Stress Injuries (RSIs) (Kuntz, 2000:1–14) and more than 600,000 workers miss time at work each year because of them[5]. Thirty five million work days are lost per year[6].

1.1. The Problem

- The thrust of several workplace violence prevention and protection programs in organisations is to maintain a safe haven conducive for work and devoid of threat, verbal abuse, physical assaults and homicide. In spite of the existence of these violence protection programs, the rate of workplace violence is on the increase. Organisations have spent time, money and other resources with minimal returns on such investments. Violence has continued to breed poor morale and poor image for the organisation, making it difficult to recruit and keep staff. It has also increased costs associated with absenteeism, higher insurance premiums and legal fees, fines and compensation payments where negligence is proven.In most workplaces where risk factors can be identified, the risk of assault can be prevented or minimized if employers take appropriate precautions. Whereas some of these risks can be clearly identified, others are largely remote in operation and effect. Also, the problem is whether the easily identifiable risks as opposed to the remote risks are the worst culprits militating against violence prevention and protection. What is also not yet very clear however is whether or not or further still, which policy prevention strategy best suits the various risks. Further compounding the problem is the apparent uncertainty as to the cost-benefit trade-off of the various policy prevention strategies. What is the comparative advantage of adopting a zero tolerance safety policy? Is the cost of implementing such a policy lower or higher than the benefits derivable? How does the cost of implementation compare with the amount of loss that would have been incurred as a result of the occurrence of violence?

1.1.1. Objectives of the Study

- It is therefore a major objective of this paper to unravel and analyse the cost benefit trade-off of implementing zero tolerance safety policies. Specifically, the paper seeks:1) To determine the risk factors militating against violence prevention and protection.2) To investigate the potency of zero tolerance safety policies in the reduction of workplace violence and costs.3) To compare the costs of implementing zero tolerance safety policies with the benefits derivable.

1.1.2. Methodology

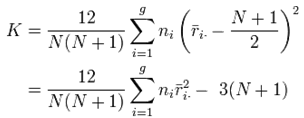

- The research design used for the study is the survey research method. Primary data for the study were sourced from four hospitals and clinics in central Nigeria. The four categories of hospitals were purposively sampled for purposes of ensuring a good representation of all hospitals which represented a broad spectrum of health care providers in central Nigeria. They include Jos University Teaching Hospital (JUTH), Sauki Hospital, New Health Clinic and Jos North Primary Healthcare clinic. Convenient sampling technique was used to select 103 senior personnel of the hospitals comprising of medical doctors, nurses, midwives and top management staff. For its data collection, a suitable Likert Scale (5 point) questionnaire was designed and developed. Respondents were requested to determine the idea of agreement or disagreement on the 16 statements under the three sections contained in the instrument. The data so collected was then analyzed using the Kruskal Wallis test statistic. The Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance by ranks named after William Kruskal and W. Allen Wallis is a non-parametric method for testing equality of population medians among groups. It is identical to a one-way analysis of variance with the data replaced by their ranks. It is an extension of the Mann-Whitney U test to 3 or more groups. The test statistic is given by[7]:

where: ni is the number of observations in group i ; rij is the rank (among all observations) of observation j from group I; N is the total number of observations across all groups and

where: ni is the number of observations in group i ; rij is the rank (among all observations) of observation j from group I; N is the total number of observations across all groups and  is the average of all the rij.However, the Kruskal-Wallis computer-statisticalpackage for social sciences (SPSS)-16.O version was used to test the three hypotheses.

is the average of all the rij.However, the Kruskal-Wallis computer-statisticalpackage for social sciences (SPSS)-16.O version was used to test the three hypotheses.2. Theoretical Perspective

- Workplace violence can be any act of physical violence, threats of physical violence, harassment, intimidation, or other threatening, disruptive behaviour that occurs at the work site[1]. It refers to incidents where people are abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances relating to their work, involving an explicit or implicit challenge to their safety, well-being or health.Workplace violence can strike anywhere and no one is immuned. It can affect and involve employees, clients, customers and visitors. Some workers, however, are at increased risk. Among them are workers who exchange money with the public; deliver passengers, goods, or services; or work alone or in small groups, during late night or early morning hours, in high-crime areas, or in community settings and homes where they have extensive contract with the public. This group includes health-care and social service workers such as visiting nurses, psychiatric evaluators, and probation officers, community workers such as gas, electricity and water utility employees, phone and cable TV installers, and letter carriers; retail workers; and taxi drivers.Workplace violence can also originate from employees or employers and threatens employers and other employees. For employees, violence can cause pain, distress and even disability or death. Physical attacks are obviously dangerous but serious or persistent verbal abuse or threats can also damage employees’ health through anxiety or stress.By understanding the cause of violence, the organisation is better able to eliminate, reduce and manage the risk of it occurring. There are four main types of work related violence: (1) Criminal violence perpetrated by individuals who have no relationship with the organisation or victim. Normally, their aim is to access cash, stock, drugs, or perform some other criminal or unlawful act. (2) Service user violence perpetrated by individuals who are recipients of a service provided in the workplace or by the victim. This often arises through frustration with service delivery or some other by-product of the organisation’s core business activities. (3) Worker-on-worker violence perpetrated by individuals working within the organisation; colleagues, supervisors, managers, etc. This is often linked to protest against enforced redundancies, grudges against specific members of staff, or in response to disciplinary action that the individual perceives as being unjust. (4) Domestic violence perpetrated by individuals outside the organisation, but who have a relationship with an employee. For example: partner, spouses or acquaintances. This is often perpetrated within the work setting simply because the offender knows where a given individual is during the course of a working day[2].What can employers or managers do to protect employees, clients, customers and visitors? One of the best protections employers can offer their workers is to establish a zero-tolerance policy towards workplace violence. This policy should cover all workers, patients, clients, visitors, contractors, and anyone else who may come in contact with company personnel[8]. By assessing their worksites, employers can identify methods for reducing the likelihood of incidents occurring. OSHA believes that a well written and implemented Workplace Violence Prevention Program, combined with engineering controls, administrative controls and training can reduce (or eliminate) the incidence of workplace violence in both the private and public workplaces. This can be a separate workplace violence prevention program or can be incorporated into an injury and illness prevention program, employee handbook or manual of standard operating procedures. It is critical to ensure that all workers know the policy and understand that all claims of workplace violence will be investigated and remedied promptly.The USDA also encourages employees, managers and supervisors, agency heads, human resources staff, employee assistance program counselors, labour unions, security / facilities staff, law enforcement staff and conflict resolution offices to be familiar with their safety rights and responsibilities. A sound prevention plan is the most important and, in the long run, the least costly portion of any agency’s workplace violence program. This programme should cover pre-employment screening of potential employees; maintenance of a safe workplace (security); Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR); threat assessment team (to assess the potential of workplace violence and, as appropriate, develop and execute a plan to address it).; and Agency Work and Family Life Programs (such as flexi place, child care, maxiflex) to identify and modify policies and procedures which cause negative effects on the workplace climate[1].The implementation of zero-tolerance safety policy is a two sided coin. The elimination or reduction of workplace violence leads to a violence-free organisation which enjoys substantial savings in costs, increased productivity and reduction in moral and legal tussles. The other side of the coin portends the two types of costs to be incurred by management when violence occurs. These are direct costs in the form of compensation payable to the dependents of the victims if the violence is fatal, and medical expenses incurred in treating the patient if the violence on the employee is non-fatal. The management however, is not liable to meet the direct costs if the victim is insured. More serious than the direct cost are the indirect or hidden costs which the management can not avoid. In fact, the indirect costs are three to four times higher than the direct costs[9].Let us face it: violence is expensive. Aside from workers compensation (direct costs) mentioned above, consider the indirect costs of violence: cost of wages paid for time lost; cost of damage to material and equipment or amount of loss through robbery attacks; cost of overtime work by others required by the violence; cost of wages paid to supervisors while their time is required for activities resulting from the violence; cost of decreased output of the injured worker after he or she returns to work; costs associated with the time it takes for a new worker to learn the job; uninsured medical costs borne by the company; and cost of time spent by higher management and clerical workers to investigate or to process workers’ compensation forms[10]. As long as the outlays required for the implementation of zero-tolerance safety measures are less than the benefits derived, the enforcement of the policies is worth it and the organisation, employees and the society will benefit.

3. Discussion and Implications of Findings

- The questionnaire was distributed to 135 senior level staff of the four selected hospitals and clinic and 103 copies representing 76.3% were completed and returned as shown in Table 1.1.

|

3.1. Hypothesis I: The Identification of Risk Factors Significantly Impact Violence Prevention and Protection

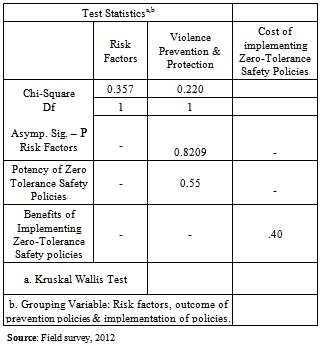

- The result of the Kruskal-Wallis test showing therelationship between the identification of risk factors and violence prevention and protection (as shown on Table 1.2) reveal that the risk factors examined militate against violence prevention and protection by 82 %.

|

3.2. Hypothesis 2: Zero-tolerance Safety Policies Significantly Account for Reduction in Workplace Violence and Costs

- The result of the Kruskal-Wallis test showing the relationship between zero-tolerance safety policies and workplace violence and costs (as shown on Table 1.23) reveals that zero- tolerance safety policies reduce workplace violence and costs by 55%.Statistical DecisionLevel of significance = 0.05; Sample size (n) = 103; Test statistics = Kruskal-Wallis; Decision criterion = Reject Ho if Kc Calculated > kt = 0.5. Since Kc = 0.55 > 0 kt = 0.5, we reject Ho and accept H1. It was concluded that zero-tolerance safety policies significantly account for reduction in workplace violence in central Nigerian hospitals. The hospitals under investigation reveal that the absence of active safety policies to protect employees from violence while on transit to and from work, contagious diseases and practices, attacks from colleagues and danger in handling cash, drugs and other hospital properties have led to increase in the occurrence of violence and the costs of handling these threats.The result agrees with the findings of Aswathappa[9] which reveal that a violence-free organization enjoys certain benefits. To Aswathappa, direct costs in the form of compensation and medical expenses are incurred when violence takes place on an employee but more serious than the direct costs are the indirect or hidden costs which the management cannot avoid. The indirect costs are three to four times higher than the direct costs. Hidden costs include loss on account of down-time of operators, slowed- up production rate of other workers, materials spoiled and labor for cleaning, and damages to equipment

3.3. Hypothesis 3: The Benefits of Implementing Zero-tolerance Safety Policies are Significantly Greater than the Cost of Implementation

- The result of the Kruskal-Wallis test showing the relationship between the benefits of implementing zero- tolerance safety policies and the cost of implementation (as shown on Table 1.2) reveal that the benefits of implementing zero-tolerance safety policies are greater than the cost of implementing such policies by 40%.Statistical DecisionLevel of significance = 0.05; Sample size (n) = 103; Test statistics = Kruskal-Wallis; Decision criterion = Reject Ho if Kc Calculated > kt = 0.5. Since Kc = 0.4 ˂ kt = 0.5, we accept Ho and reject H1. It was concluded that the cost of implementing zero - tolerance safety policies are by far greater than the benefits of implementation. The hospitals under investigation suggest that central Nigerian hospitals spend so much on security with little results. Also, in spite of the hospitals’ preventive measures, there is a high rate of disease contagion, insults, rumor mongering, hatred, tension, aggression, public assault and general insecurity to life, cash, drugs and other organizational properties.If organisations are concerned with efficiency and profits, why should they spend money to create conditions that make them run at a loss? The answer is the profit motive itself. The cost of violence can be, and for many organisations is, a substantial additional cost of doing business. The direct cost of violence to an employer shows itself in the organization’s workers compensation’s premium. The costs is determined by the insured‘s violence history. Indirect costs, which generally far exceed direct costs, must also be borne by the employer. These include wages paid for time lost due injury, damage to equipment and materials, personnel to investigate and report on accidents , and lost production due to work stoppages and personnel changeover[13]. The impact of these indirect costs can be seen from statistics that describe the costs of violence for American industry as a whole[14]. The Abstract reports that in 1983, workers compensation cost employers approximately $18 billion. Violence additionally cost employers billions in wages and lost production. The significance of this latter figure is emphasized when we note this cost is approximately ten times greater than losses caused by strikes, an issue that has historically received much public attention[13]. Ashford[15] brings the issue to rest by asserting that as long as the outlays required for preventive measures are less than the social costs of disability among workers, higher fatality rates, and the diversion of medical resources, the enforcement of safety and health standards is well worth it and society will benefit.

4. Conclusions

- In most workplaces where risk factors can be identified, the risk of assault can be prevented or minimized if employers take appropriate precautions. Also, widely varying approaches and strategies to workplace violence prevention and protection exist. One of the best protections employers can offer their workers is to establish a zero-tolerance policy toward workplace violence. Therefore, the establishment of a zero-tolerance policy significantly reduces workplace violence and makes it a safe haven for workers to put in their best. It is also worth noting that the cost of implementing zero-tolerance policies for workplace violence prevention and protection can be higher than the intended benefits

5. Recommendations

- The Occupational Safety and Health departments of organizations should identify risk factors in the workplace early enough to prevent or minimize violence in the workplace. Organizations should establish zero-tolerance policies. These policies should cover all workers, patients, clients, visitors, contractors, and anyone else who may come in contact with company personnel. In addition, employers should provide safety education for employees so that they know what conduct is not acceptable; what to do if they witness or are subjected to workplace violence and how to protect themselves; and how to recognize, avoid, or diffuse potentially violent situations. Also, organisations should secure the workplace (where appropriate) to install video surveillance, extra lighting, and alarm systems and minimize access by outsiders through identification of badges, electronic keys and guards; provide drop safes to limit the amount of cash on hand; instruct employees not to enter any location where they feel unsafe: and equip field staff with cellular and hand-held alarms or noise devices and require them to prepare a daily work plan and keep a contact person informed of their location throughout the day.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML