-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2013; 3(4): 102-108

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20130304.02

Perceptual Differences and the Management of People in the Organization

Wurim Ben Pam

National Directorate of Employment, P. O. Box, 6853, Jos-Plateau State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Wurim Ben Pam, National Directorate of Employment, P. O. Box, 6853, Jos-Plateau State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

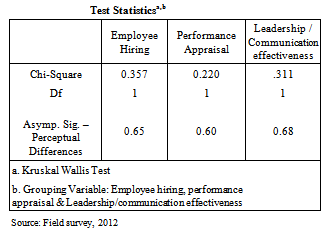

People are all unique with different ways of looking at and understanding their environment and the people within it. These perceptual differences may affect the management of people within it. The principal objective of this paper is to unravel the impact of these differences on the management of organizational people and the power of the perceptual process in guiding our behavior for effective worker-management relationships in the Public sector of Nigeria. Three hypotheses in line with these objectives were drawn and tested based on the data gathered through a questionnaire. The survey investigation method was used in collecting data and the Kruskal- Wallis test statistic was used to analyze the data. The results show that perceptual differences distort and affect the hiring of employee, performance appraisal, and leadership and communication effectiveness at 0.65, 0.60 and 0.68 respectively. Based on the aforementioned, the paper concluded that circumstances like stereotyping, Halo effect, perceptual defense, projection, attribution and self-fulfilling prophecy-the Pygmalion effect are encountered in the workplace which in turn affect the management of people in areas like employee hiring, performance appraisal, leadership and communication. The paper recommends employee education and training, and the identification of valid individual differences, equity and the construction of a hierarchical framework in solving perceptual differences for effective organizational management.

Keywords: Perception, Management, Employees, Organisation, Differences, People, Stereotyping, Halo Effect, Attribution

Cite this paper: Wurim Ben Pam, Perceptual Differences and the Management of People in the Organization, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 3 No. 4, 2013, pp. 102-108. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20130304.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- To interact effectively - present ourselves and communicate appropriately, work with people in relationships and groups or lead them - we must have a grasps of what others are thinking and feeling, including their motives, beliefs, attitudes and intentions. This is so because people are all unique. There is only one you. We all have our own ‘world’, our own way of looking at and understanding our environment and the people within it. A situation may be the same but the interpretation of that situation by two individuals may be vastly different. (1, p435)Robbins (Cited by 2, p1) sees perception as a set of processes by which individuals organise and interpret their sensory impressions in order to give meaning to their environment. Perception can also be seen as: a cognitive process that enables us to interpret and understand our surroundings. (3) In other words, perception basically refers to the manner in which people organise, interpret and experience ideas and use stimulus materials in the environment so that they satisfy their needs.As already mentioned, perceptual differences are so varied and have become important dynamite for organisational managers when dealing with other people and events in the work setting. It is important therefore, to note that the differences in perception and the associated feelings about others in life and in the workplace are influenced by the information we receive from the environment. And this invariably affects the way people are managed in the organisation.All human beings use information stored in their memories to interpret and interact with others. As a result, people constantly strive to make sense of their surroundings. The resulting knowledge influences our behaviour and helps us navigate our way through life. This reciprocal process of perception, interpretation, and behavioral response also applies at work and therefore affects the management of people in the organisation.

1.1. Statement of the Proplem

- The realization of an efficient and effective management system in the organisation, to a greater or lesser extent, depends on how goals, policies, principles, values, objectives, mission statements, instructions and other forms of communications are received, organised, interpreted and acted upon by both employees and top management. Different people perceive things differently. The problem is made even more complicated by the fact that a plethora of forces exert varying degrees of influence by shaping and sometimes distorting perception. Some of these factors are the perceiver, objects or targets being perceived and the situation in which perception takes place. The result includes hallo effect, stereotyping, perceptual defense, projection, self-fulfilling prophecy, and attribution. What is not yet very clear, however is whether or not, or further still, which of these areas of perceptual differences positively or negatively affect the management of people in particular, and the organisation in general. Previous studies by Mullins and Kreitner have attested to the fact that certain factors lead to perceptual differences in people.(1-3) These perceptual differences affect the management of people in the workplace and would need to be carefully explained. It is therefore a major objective of this paper to unpack and understand the power of the perceptual process in guiding our behaviour for effective worker-management relationships which will in turn enhance the realization of proactive management systems within organisations. The specific objectives of the study are as follows:1) To assess the impact of the perceptual differences on employee hiring (recruitment and selection).2) To analyze the impact of perceptual differences on performance appraisal.3) To determine the extent to which perceptual differences affect the effectiveness of leadership and communication

1.1.1. Methodology

- The study is a survey to find out how perceptual differences affect the management of people in five public sector organisations. Primary data for the study were sourced from five public sector organisations namely: National Directorate of Employment (NDE), Power Holding Company of Nigeria (PHCN), Plateau State Water Board (PSWB), Federal Ministry of Finance (FMF) and Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC). The population of the study includes all the 10,127 top, middle and lower management staff of the five organisations. Given that the population of the study is finite, the Taro Yamane (1964) statistical formula for selecting a sample was applied. The formula is given as:

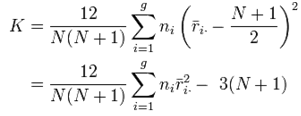

Where: n = Sample size; N = Population; e = level of significance (or limit of tolerance error) in this case 0.05; 1 = Constant value. This gives a sample size of 385.For its data collection, a suitable Likert Scale (5 point) questionnaire was designed and developed. Respondents were requested to determine the idea of agreement or disagreement on the 18 statements under the two sections contained in the instrument. The data so collected was then analyzed using the Kruskal Wallis test statistic. The Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance by ranks named after William Kruskal and W. Allen Wallis is a non-parametric method for testing equality of population medians among groups. It is identical to a one-way analysis of variance with the data replaced by their ranks. It is an extension of the Mann-Whitney U test to 3 or more groups. The test statistic is given by (4):

Where: n = Sample size; N = Population; e = level of significance (or limit of tolerance error) in this case 0.05; 1 = Constant value. This gives a sample size of 385.For its data collection, a suitable Likert Scale (5 point) questionnaire was designed and developed. Respondents were requested to determine the idea of agreement or disagreement on the 18 statements under the two sections contained in the instrument. The data so collected was then analyzed using the Kruskal Wallis test statistic. The Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance by ranks named after William Kruskal and W. Allen Wallis is a non-parametric method for testing equality of population medians among groups. It is identical to a one-way analysis of variance with the data replaced by their ranks. It is an extension of the Mann-Whitney U test to 3 or more groups. The test statistic is given by (4): where: ni is the number of observations in group i ; rij is the rank (among all observations) of observation j from group I; N is the total number of observations across all groups and

where: ni is the number of observations in group i ; rij is the rank (among all observations) of observation j from group I; N is the total number of observations across all groups and  is the average of all the rij.However, the Kruskal-Wallis computer-statistical package for social sciences (SPSS)-16.O version was used to test the hypothesis.

is the average of all the rij.However, the Kruskal-Wallis computer-statistical package for social sciences (SPSS)-16.O version was used to test the hypothesis.2. Conceptual Framework

- Perception is a cognitive process that enables us to interpret and understand our surroundings. The study of how people perceive one another has been labeled social cognition and social information processing. This is in contrast to the perception of objects. Social cognition is the study of how people make sense of other people and themselves. It therefore focuses on how ordinary people think about people and how they think about themselves. The study of social cognition leans heavily on the theory and methods of cognitive psychology.(5) To lay a conceptual framework for the study, the Kreitner Information processing Model is adopted and as such, this section focuses on the said information processing model of perception.

2.1. Perception as Information Processing

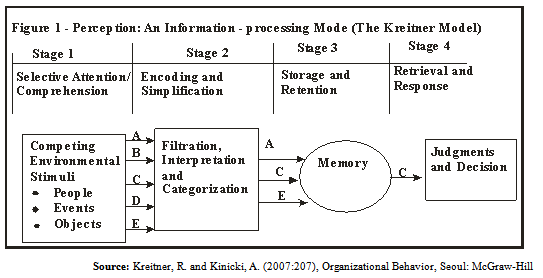

- Perception is a complex cognitive process with information selected, cognitively organised in a specific fashion, and then presented. It is a subjective process (preference based).(2) Perception therefore, involves a four-stage information processing sequence. Figure1 below illustrates a basic information-processing model of perception. Three of the stages in this model-selective attention/comprehension, encoding and simplification, and storage and retention-describe how specific information and environmental stimuli are observed and stored in memory. The fourth and final stage, retrieval and response, involves turning mental representation into real-world judgement and decisions. (3)

| Figure 1. Perception: An Information-processing Mode |

2.2. Implications of Perceptual Differences on Human Capital Management

- We have seen that differences in perception result in different meanings to the same stimuli. Every person sees things in his or her own way and as perceptions become a person’s reality, this can lead to misunderstandings, confusion, disobedience, quarrels, low productivity, inefficiency, demotivation, absenteeism and employee turnover.There are seven main features which can create particular difficulties and give rise to perceptual problems in the management of people in the work place. These are: stereotyping, halo effect, perceptual defense, projection, attribution and self-fulfilling prophecy- The Pygmalion effect.Stereotyping is the tendency to ascribe positive or negative characteristics to a person on the basis of a general categorization and perceived similarities. The perception of that person may be based more on certain expected characteristics than on the recognition of that person as an individual. Stereotype is an individual’s set of beliefs about the characteristics or attributes of a group. Stereotypes are not always negative. For example, the belief that engineers are good at mathematics is certainly part of a stereotype. Stereotypes may or may not be accurate. (9, p110) The Halo Effect is the process by which the perception of a person is formulated on the basis of a single favourable or unfavorable trait or impression. The halo effect tends to shut out other relevant characteristics of that person. When we draw a general impression about an individual on the basis of a single characteristic such as intelligence, sociability or appearance a ‘Halo Effect’ is operating. The reality of Halo Effect was confirmed in a classic study in which subjects were given a list of traits such as intelligent, skilful, practical, industrious, determined and warm and were asked to evaluate the person to whom those traits apply. When those traits were used, the person was judged to be wise, humorous, popular or imaginative. But when the same was modified- cold was substituted for warm- a completely different set of perceptions was obtained. Clearly, the subjects were allowing a single trait to influence the overall impression of the person being judged. (2, p4)A particular danger with the halo effect is that where judgments are made on the basis of readily available stimuli, the perceiver may become ‘perceptually blind to subsequent stimuli at variance with the original perception, and (often subconsciously) notice only those characteristics which support the original judgement. The process may also work in reverse: the rusty halo effect. This is where general judgments about a person are formulated from the perception of a negative characteristic. For example, a candidate is seen arriving late for an interview. There may be a very good reason for this and it may be completely out of character. But on the basis of that one particular event, the person may be perceived as a poor time-keeper and unreliable.Perceptual defense is the tendency to avoid or screen out certain stimuli that are perceptually disturbing or threatening. People may tend to select information which is supportive of their point of view and choose not to acknowledge contrary information. For example, a manager who has decided recently to promote a member of staff against the advice of colleagues may select only favourable information which supports that decision and ignore less favourable information which questions that decision.Projection, which is the act of attributing or projecting one’s own feelings, motives or characteristics to other people, is a further distortion which can occur in the perception of other people. Judgement of other people may be more favourable when they have characteristics largely in common with, and easily recognized by the perceiver. Projection may also result in people exaggerating undesirable traits in others that they fail to recognize in themselves.Self Fulfilling Prophecy: The Pygmalion Effect. Here, someone’s high expectations for another person result in high performance for that person. A related self-fulfilling prophecy effect is referred to as the Galatea Effect. Kreitner maintains that the Galatea effect occurs when an individual’s high self-expectation for him- or herself lead to high performance. The key process underlying both the Pygmalion and Galatea effects is the idea that people’s expectations or beliefs determine their behaviour and performance, thus serving to make their expectations come true. (3, p221) In other words, we strive to validate our perceptions of reality, no matter how faulty they may be. The self-fulfilling prophecy was first demonstrated in an academic environment. After giving a bogus test of academic potential to students from grades 1 to 6, researchers informed teachers that certain students had high potentials for achievement. In reality, students were randomly assigned to the “high potential” and “control” (normal potential) groups. Results showed that children designated as having high potential obtained significantly greater increases in both IQ scores and reading ability than did the control students.Attribution is another source of concern. The attribution theory is based on the premise that people attempt to infer causes for observed behaviour. Rightly or wrongly, we constantly formulate cause-and-effect explanations for our own and others’ behaviour. Attribution statements such as the following are common: “Joe drinks too much because he has no willpower: but I need a couple of drinks after work because I’m under a lot of pressure.” Formally defined, causal attributions are suspected or inferred causes of behaviour. Even though our causal attributions tend to be self-serving and are often invalid, it is important to understand how people formulate attributions because they profoundly affect organisational behaviour. For example, a supervisor who attributes an employee’s poor performance to a lack of effort might reprimand that individual. However, training might be deemed necessary if the supervisor attributes the poor performance to a lack of ability. Generally speaking, people formulate causal attributions by considering the events preceding an observed behaviour.

3. Results

- The questionnaire was distributed to 385 middle level staff of the five selected organisations and 349 copies representing 92% were completed and returned. We set out to provide the necessary lead for empirical examination of the impact of perceptual differences in the management of people in the organisation. In addition, the study tried to assess the extent to which perceptual differences specifically affects the hiring, performance appraisal of employees and management effectiveness.For these and other purposes, we formulated these hypotheses as follows:

3.1. Hypothesis I

- Perceptual differences significantly impact on employee hiring (recruitment and selection)84.5% of total respondents agreed that interviewers make hiring decisions based on the brief moment spent with the applicant during interview sessions which often results in stereotyping, Halo effect, perceptual defense and projection. About 9.74% thought otherwise, while 5.73% was undecided on the question posed. The result of the Kruskal-Wallis test showing the impact of perceptual differences on employee hiring (see Table 1) reveal that perceptual differences account for 65% impact on employee hiring.

3.1.1. Statistical Decision

- Level of significance = 0.05; Sample size (n) = Test statistics = Kruskal-Wallis; Decision criterion = Reject Ho if Kc Calculated > kt = 0.5. Since Kc = 0.65 > kt = 0.5, we reject Ho and accept H1. It was concluded that perceptual differences in Nigeria Public organisations significantly impact on employee hiring (recruitment and selection).

|

3.2. Hypothesis 2

- Perceptual differences significantly impact on performance appraisal60.5% of the total respondents agreed that the performance appraisal process include faulty schemes about what constitutes good versus poor performance. However, about 34.7% felt that the performance appraisal process does not contain faulty schemata

3.2.1. Statistical Decision

- Level of significance =0.05; Sample size = 349, Test statistics = Kruskal-Wallis; Decision criterion = Reject Ho if K calculated > Kt = 0.5From table 1, since Kc = .60 > Kt = 0.5, we reject Ho and accept H1. It was concluded that perceptual differences significantly impact on performance appraisal in Nigeria Public organisations.

3.3. Hypothesis 3

- Leadership and Communication effectiveness are significantly impacted by perceptual differences.86% of total respondents agreed that leadership and communication effectiveness is impacted by perceptual differences. About 8.8% thought otherwise, with about 4.9% remaining indifferent.

3.3.1. Statistical Decision

- Level of significant = 0.05; Sample size = 349; Statistic = Kruskal-Willis; Decision criterion = Reject Ho if Kc calculated > Kt = 0.5.From Table 1, Since Kc = .68 > Kt = 0.5, we reject Ho and accept H1. It was concluded that leadership and communication effectiveness is Nigeria Public organisation significantly is impacted by perceptual difference.

4. Discussion and Implications of Findings

- Result of the test of the first hypothesis indicates that employee recruitment and selection is significantly affected by a plethora of factors that contribute in distorting perception in Nigerian public organisations. (α = 0.05, Kc = 0.65 > Kt = 0.5). We thus conclude that the two variables are to a large extent associated. The result of the test of hypothesis 1 agrees with the findings of Otting (2). To Otting, Interviewers are supposed to make hiring decisions based on their impression of how an applicant fits the perceived requirements of a job. However their findings show that many of these decisions are made within the first 10 minutes of an interview. Inaccurate impressions in either direction produce poor hiring decisions. Moreover, interviewers with racist or sexist schemata can undermine the accuracy and legality of hiring decisions. Those invalid schemata need to be confronted and improved through coaching and training. Failure to do so can lead to poor hiring decisions. For example, a study of 46 male and 66 female financial-institution managers revealed that their hiring decisions were biased by the physical attractiveness of applicants. More attractive men and women were hired over less attractive applicants with equal qualifications. (10, p11-21) On the positive side, however, another study demonstrated that interviewer training can reduce the use of invalid schema. Training improved interviewers’ ability to obtain high-quality, job-related information and to stay focused on the interview task. Trained interviewers provided more balanced judgments about applicants than did non trained interviewers (11, p55)Result of the test of the second hypothesis shows that performance appraisal is significantly affected by perceptual differences. (α = 0.05, Kc = 0.60 > Kt = 0.5). We thus conclude that the two variables are to a large extent associated. The result agrees with Mayer (12) and Bommer (13) whose separate researches demonstrate that faulty schemata about what constitutes good versus poor performance can lead to inaccurate performance appraisal, which erodes work motivation, commitment, and loyalty. For example, a study of 166 production employees indicated that they had greater trust in management when they perceived that the performance appraisal process provided accurate evaluations of their performance.(12, 13) Therefore, it is important for managers to accurately identify the behavioural characteristics and results indicative of good performance at the beginning of a performance review cycle. These characteristics then can serve as the standard for evaluating employee performance. The importance of using objective rather than subjective measure of employee performance was highlighted in a meta-analysis involving 50 studies and 8,341 individuals. Results revealed that objective and subjective measures of employee performance were only moderately related. The researchers concluded that objective and subjective measures of performance are not interchangeable. Managers are thus advised to use more objectively based measures of performance as much as possible because subjective indicators are prone to bias and inaccuracy. In those cases where the job does not possess objective measures of performance, however, managers should still use subjective evaluations. Furthermore, because memory for specific instances of employee performance deteriorates over time, managers need a mechanism for accurately recalling employee behavior (Sanchez et al, 1996:3-10). Research reveals that individuals can be trained to be more accurate raters of performance. (14)From testing the third hypothesis, it was shown that leadership and communication effectiveness in Nigeria public organisations is significantly impacted by perceptual differences. The result agrees with Knippenberg whose research demonstrates that employees’ evaluations of leader effectiveness are influenced strongly by their schemata of good and poor leaders. A leader will have a difficult time influencing employees when he or she exhibits behaviour contained in employees’ schemata of poor leaders. A team of researchers investigated the behaviors contained in our schemata of good and poor leaders. Good leaders were perceived as exhibiting behaviours like: assigning specific tasks to group members; telling others that they had done well; setting specific goals for the group; letting other group members make decisions; trying to get the group to work as a team and maintaining definite standards of performance. In contrast, poor leaders were perceived to exhibit behaviors like: telling others that they had performed poorly; insisting on having their own way; doing things without explaining themselves; expressing worry over the group members’ suggestions, frequently changing plans and letting the details of the task become overwhelming.

5. Conclusions

- Social cognition is the window through which we all observe, interpret, and prepare our responses to people and events. A wide variety of managerial activities, organisational processes, and quality-of-life issues are thus affected by perception. Also, the process of perception links individuals to their social world. Although we all see the world through our own ‘colored spectacles’ we also have the opportunities to share our experiences with others. By learning others’ perspectives and by widening our understanding of how others may see the world, depth and variety is encouraged and problems of bias and distortion become minimized. Perception is the root of all organisational behaviour and any situation can be analyzed in terms of its perceptual connotations.The process of perception is innately organised and patterned in order to provide meaning for the individual. The process of perception is based on both internal and external factors. The organisation and arrangement of stimuli is influenced by three important factors: figure and ground; grouping; and closure. It is important to be aware of potential perceptual illusions. Arising from the research findings and conclusion, the paper recommends employee education and training. One of the key managerial challenges is to reduce the extent to which stereotypes influence decision making and interpersonal processes throughout the organization. We recommend that an organization first needs to inform its workforce about the problem of stereotyping through employee education and training. Training also can be used to help in managing employees with disabilities. Secondly, managers should identify valid individual differences that differentiate between successful and unsuccessful performers. For instance, research reveals experience is a better predictor of performance than age. Research also shows that managers can be trained to use these valid criteria when hiring applicants and evaluating employee performance. Lastly, removing promotional barriers for men and women, people of color, and persons with disabilities is another viable solution to alleviating the stereotyping problem. This can be accomplished by minimizing the differences in job experience across groups of people similar experience, coupled with the accurate evaluation of performance, helps managers to make decisions that are less influenced by stereotypes.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML