-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2013; 3(3): 52-62

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20130303.04

Relations of Perceived Autonomy and Burnout Syndrome in University Teachers

Oksana A. Gavrilyuk1, Irina O. Loginova2, Natalia Yu. Buzovkina2

1Department of Latin and Foreign Languages, Krasnoyarsk State Medical University named after Professor V.F. Voyno-Yasenetsky, Krasnoyarsk, 660022, Russia

2Faculty of Clinical Psychology, Krasnoyarsk State Medical University named after Professor V.F. Voyno-Yasenetsky, Krasnoyarsk, 660022, Russia

Correspondence to: Oksana A. Gavrilyuk, Department of Latin and Foreign Languages, Krasnoyarsk State Medical University named after Professor V.F. Voyno-Yasenetsky, Krasnoyarsk, 660022, Russia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Teaching represents nowadays a complex of stressful situations. Being unable to efficiently cope with these transformations, some teachers are becoming frustrated, dissatisfied, demotivated, physically and psychologically depleted which results in the onset of burnout syndrome. The potential of teacher personal attributes in preventing burnout syndrome development have been analyzed. The attention has been drawn to the relation between perceived university teacher autonomy and burnout syndrome.Based on the classical methods of teacher burnout and personal autonomy measurement, two questionnaires were developed and distributed among 91 teachers working in Krasnoyarsk State Medical University, Russia with the purpose to elicit participants’ responses and views on teacher burnout and teacher autonomy. The results of our investigation allow us to suggest that the development of burnout syndrome in Russian university teachers correlates with low level of perceived teacher autonomy. And vice-versa, personality attributes which ensure teacher’s perception of high and middle levels of autonomy correlate with law teacher burnout rate. Our research results suggest that teacher autonomy should be considered as a specific teacher personality trait that must be taken into account to prevent university teacher burnout.

Keywords: Burnout Syndrome, Personality Traits, Personal Autonomy, Perceived University Teacher Autonomy, Self-determination, Intrinsic Motivation

Cite this paper: Oksana A. Gavrilyuk, Irina O. Loginova, Natalia Yu. Buzovkina, Relations of Perceived Autonomy and Burnout Syndrome in University Teachers, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 3 No. 3, 2013, pp. 52-62. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20130303.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In Russia today, major transformations and innovations are having an effect on education at university level. This trend has led to an increasingly significant role for university teachers to play within their educational institutions. New expectations for university teachers’ performance and accountability make teachers face new challenges and develop new knowledge and skills. The work of teaching comprises today plenty of activities that include teaching, mastering new educational environments, developing new teaching materials, dealing with students, parents, and the community. At the same time work overload, disrespect, too much clerical work, loss of status of the teaching profession, long-term stress and anxiety are only a few examples of the stressors that today’s teachers have to cope with. Therefore teaching represents nowadays a complex of increasingly stressful situations that may have positive or negative consequences for them as well as for the students they work with. Being unable to cope in an efficient way with these transformations, some teachers are becoming frustrated, dissatisfied, depressed, demotivated, hopeless, physically and psychologically depleted. Teachers’ coping unsuccessfully with chronic stress can lead to work burnout. The latter is described by Etzion[14] as ‘a process of energy depletion and deterioration of performance caused by continuous daily pressures, rather than critical life events’. Most studies describe teachers with burnout symptoms as dogmatic about their teaching practices, cynical, indifferent persons with negative self-evaluation which suffer from mental and physical tension[14];[37]. In the context of our research it is important to reveal the potential of teacher personality traits, as the results of the latest research demonstrate their benefits for job satisfaction, enhancing people’s psychological well-being and burnout prevention [12];[50]. Personal autonomy seems to be one of these personal traits which are now attracting attention of both Russian and foreign scientists. As for the relationships between professional/job autonomy and burnout, they have been tested in several worklife areas in psychology, management and medical science. The results of these studies suggest that professional autonomy is able to moderate burnout[37]. However, no literature was found in which the relationships between the levels of professional autonomy and burnout levels were investigated among Russian university teachers. The purpose of this study is to determine the degree of perceived teacher autonomy and professional burnout in Russian university teachers and document the relationship between these two variables. This paper intends to answer the following questions: Is perceived teacher autonomy a characteristic that is negatively related to the development of burnout syndrome? Could perceived teacher autonomy provide a buffer against teacher burnout? Accordingly, the following hypothesis is formulated: The more teacher autonomy is perceived, the less likely will be teacher burnout syndrome. The organization of the study includes, firstly, a literature review of the constructs of work-related burnout and autonomy. The relationship between these phenomena is discussed and represented in a conceptual model. Secondly, the discussion of research methodology applied in this study is described. Thirdly, results are presented and interpretations of the findings are discussed.

2. Related Work

2.1. Teacher Burnout and Related Personality Factors

- A literature review proves that burnout syndrome is becoming increasingly problematic due to its enormous detrimental effect on the quality of life among teachers as well as on the quality of the teaching-learning process. Burnout syndrome has been linked to the decrease in both psychological and physical well-being and associated with high sickness rate of teachers. Originally used by Freudenberger[15] to describe a critical condition of human service workers, the term ‘burnout’ has often been associated with a high stress rate, accompanied with a state of three types of exhaustion (physical, emotional, and cognitive). This critical condition was reported to produce feelings of low self-regard, withdrawal, indifference, skepticism and cynicism. Meanwhile, A. Lasalvia and M. Tansella emphasize that burnout should be distinguished conceptually from occupational stress, which ‘refers to temporary adaptation at work, accompanied by mental and physical symptoms’[29 : 279]. In contrast, burnout is considered by the authors as ‘the final stage of prolonged occupational stress’ including ‘the development of dysfunctional attitudes and behaviours towards the recipients of one’s care or services and towards one’s job and organization’ (ibid.). It seems that burnout occurs most often among people who are unable to work in the situation of extensive stress and work pressure. Teachers, who constantly deal with people, are particularly affected by stress and burnout. Burnout has been regarded as a multidimensional construct and conceptualized in terms of three interrelated components: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment[37]. Emotionalexhaustion means emotional overextension and depletion of one's emotional resources; depersonalization involves a negative response to other people; and reduced personal accomplishment implies a feeling of negative self-evaluation [16]. Consequently, burnout affects the quality of teachers' professional performance and demotivates students. Recent research results have slightly modified the aforementioned three dimensions of burnout into emotional exhaustion, disengagement (cynicism) and ‘professional efficacy’ and expanded the understanding of depersonalization which is now seen not only as negative attitude towards service recipients, but also as person’s negative attitude to his work as a whole[4]. Burnout is usually caused by prolonged work stress and, consequently, has several stages[38]. Matteson and Ivancevich consider that the first stage of burnout development (or ‘stagnation’) involves feelings of fatigue and depression, the second stage means psychological and physical withdrawal, and below average performance, and the final stage is characterized by depersonalization, apathy, decrease in performance and doubting about one’s self-efficacy[38]. These three stages of burnout development are also called by some authors as stress (or alarm reaction), resistance, and exhaustion[4]. Consequently, burnout, as a sense of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and lack of accomplishment, can be characterized by the professional's quitting the job or the profession. Speaking about the factors affecting the development of burnout, it should be pointed out that they can be divided into two groups: internal and external factors. Recent research findings have suggested that burnout among human service workers may result from unrealistic expectations that people entering public human service careers had developed about their professions. They found that their professions did not provide the degree of autonomy and collegiality necessary for fulfilling a professional role. Thus, a correlation has been revealed between different burnout criteria and such personal traits as anxiety, emotional sensitivity, locus of control and other specific teacher-related personality factors which must be taken into account to explain teacher burnout[54]. Maslach, et al. proposed that burnout develops as a result of mismatches between professionals and their job contexts in several worklife areas (i.e. workload, control, rewards, community, fairness and values)[37]. Nias considers values as resources to avoid damaging exposure to stress and teacher burnout[42]. Professional self-efficacy is also reported to be associated with the level of burnout[3]. In Russia personal self-control functions have been studied in the context of the personal potential problem. Personal potential is regarded as a systematic organization of person’s individual and psychological features or personality strength (hardiness, optimism, purpose in life, tolerance for ambiguity, self-efficacy, etc.), ensuring this person’s capacity to act according to their sustainable internal convictions, to keep stability of semantic orientations, to work efficiently against the context of external pressure and changing environment[33]. Thus, personal potential is considered as a capacity of a person to act as a personality, as an independent, autonomous or self-regulating actor through making purposeful transformations in the external world and combining resistance to external influence with flexible reaction to external and internal transformations. The aggregate of personality variables, which has recently been designated as ‘personal autonomy’, is regarded by Leontiev and Osin as the core of personal potential[34]. To prove our hypothesis that teacher autonomy is an important personality factor which must be taken into account to explain and prevent teacher burnout it is necessary to reveal the content of the phenomenon of personal autonomy.

2.2. The Potential of Perceived Teacher Autonomy for Teacher Burnout Prevention

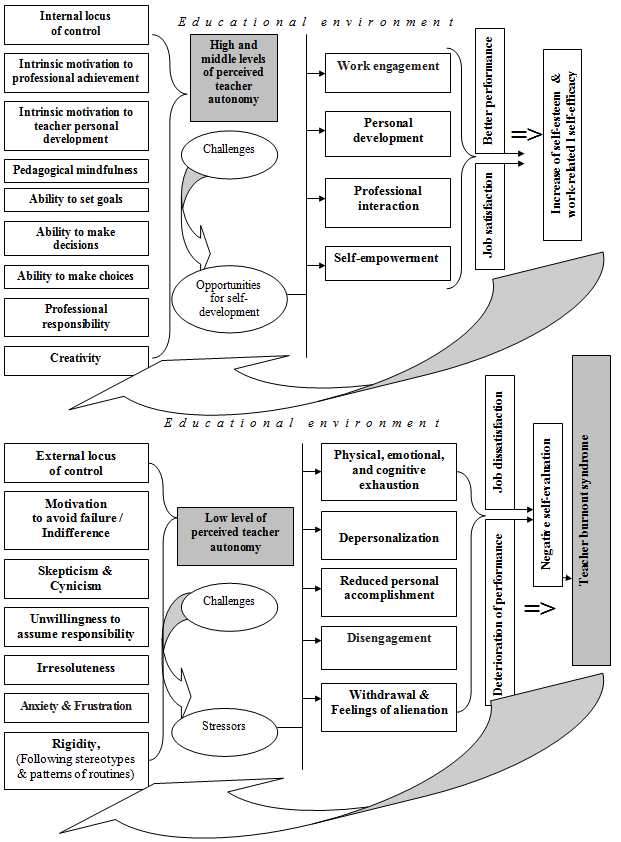

- While personal autonomy was found to be important in many works, it was rarely examined in relation to teachers and teaching. According to the review of the professional literature, teacher professional autonomy is not strictly defined and is often described in a variety of forms. Teacher autonomy is defined as ‘control one’s own work environment’[45: 173]; ‘freedom to make certain decisions’ [53: 490]; teachers’ capacity to be self-directed, based on detachment, critical reflection, decision-making and independent action[53] or ‘the capacity, freedom, and/or responsibility to make choices concerning one’s own teaching’[1]. Generally, most definitions point to one common aspect, according to which teacher autonomy involves self-governing and capacity for self-directed professional development.In this research, following the idea of Kamii and Housman, teacher autonomy is considered as an ability, not a right to be self-governing[23]. On this basis we use in the presented paper the term ‘perceived teacher autonomy’ which seems to prevent confusion between ‘provided’ and ‘perceived’ autonomy and correspond to the Myers and McCaulley’s definition of perception as ‘all the ways of becoming aware of things, people, happenings, or ideas’[40: 1]. This approach makes responsibility and mindfulness to be often considered as the most important aspects of teacher autonomy[33];[41]. The investigation of perceived teacher autonomy potential for teacher burnout prevention required a more detailed study of Ryan and Deci’s Self-Determination Theory (SDT). According to SDT, the need for autonomy is the central need of an individual and is a need to have a choice and act with self-determination. Satisfaction of this need is regarded as an important condition, which determines psychological well-being, optimal functioning and healthy development of a personality. And conversely, frustration of this need seems to lead to the decrease of psychological well-being and the degradation of activity[50]. Continuing this idea, it has also been assumed that autonomy is one of the marks of a professional[20] and that a professional functioning in an autonomous manner will experience satisfaction with his or her job[8]. Extrapolating the above mentioned to the context of university teaching practice, we can suggest that lack of perceived teacher autonomy may lead to the decrease of their psychological well-being and the degradation of his professional functioning, these disturbances being often associated with teacher burnout. The concept of self-determination is closely connected in the psychological literature to the concept of will which is defined as a capacity of a person to make choice proceeding from the information received from the environment and from the processes occurring inside of the person[9]. According to SDT, there are autonomous and controlling forms of motivation. As Ryan & Connell show in their work, different types of behaviour are located on a continuum of perceived autonomy, subject to perceived locus of causality (PLOC)[48]. The authors suggested five types of perceived motivations: external, introjected, identified, integrated and intrinsic. The latter, intrinsic motivation, is regarded by Ryan and Deci to be autonomous and reported as ‘the doing of an activity for its inherent satisfaction rather than for some separable consequence’. This type of motivation is described by the authors as satisfying ‘personally relevant goals and services’[49: 56]. According to Ryan and Deci, intrinsically motivated person is moved to act by intrinsic motivation rather than because of external pressures or rewards. Intrinsic motivation is associated by the authors with ‘increased engagement and persistence in tasks’[49]. Enlarging these outcomes and extrapolating them into the context of teaching, Pearson and Moomaw define teacher autonomy as ‘a common link that appears when examining teacher motivation, job satisfaction, burnout,professionalism, and empowerment’[46]. According to the authors, among teacher autonomy intrinsic factors there are ‘desire to assist students to accomplish goals, desire to make a difference in society and sense of achievement when students learn’[46: 39]. Thus, the complex of the above mentioned teacher desires and sense of professional achievement may be regarded as intrinsic motivation to professional achievement.Taking into account that being autonomous often requires teacher’s mastering new skills and competences to deal with new challengers, an autonomous teacher should also be a lifelong learner[17]. On this basis, motivation to autonomy in teaching should involve not only intrinsic motivation to professional achievement, but intrinsic motivation to teacher personal development. Drawing on Kunda's work on motivation in psychology[27], we assume that autonomy in teaching is ensured by intrinsic motivation to professional achievement and personal development, which can lead to the generation and adoption of teacher professional and personal development goals and affects the outcome of the reasoning or behavioural task intended to satisfy those goals. Teacher intrinsic motivation to professional achievement and personal development seems to underlie a better performance in teaching. This idea has been proved in a number of studies considering the more autonomous motivations as related to positive outcomes and the more controlled motivations as associated with negative outcomes across domains as varied as health care, education, politics, etc.[48]. It is reported that autonomy involves increased engagement and persistence in tasks or goal commitment defined as one’s determination to reach a goal[30]. Thus, autonomy makes the person generate great efforts, accompanied by feelings of vitality and energy[43]. Perceiving their engagement in various teaching tasks as interesting and meaningful, autonomously-motivated teachers will experience less exhaustion. Meanwhile, it is theorized that employees who are more committed to their organization’s mission, goals and objectives will feel less job stress than those who are less committed[18]. Accordingly, we can assume that the more teacher autonomy is perceived, the less likely will teacher feel job stress. And, as it was previously said, burnout results from prolonged occupational stress. It makes us suggest that the more teacher professional autonomy is perceived, the less likely will be teacher burnout syndrome.According to Little, Hawley, Henrich, and Marsland, the development of teacher autonomy is associated with a process of internalization or personal agency also defined as the sense of personal empowerment / psychological empowerment / self-empowerment[35]. The latter is reported by Little et al. to imply self-belief, trust, and self-leadership and involve both knowing one’s goals and having what it takes to achieve them (ibid.). Empowerment is often represented as a process of controlling decisions and resources influencing the quality of person’s life. Campion, Medsker, and Higgs define personal empowerment as the capacity to make decisions and to be responsible for their outcomes[5]. Regarding personal empowerment in its psychological aspect, Oladipo describes it as ‘an individual’s cognitive state characterized by a sense of perceived control, competence, and goal internalization’[44: 121]. According to the author, this ‘multi-faceted construct reflects the different dimensions of being psychologically enabled, and is conceived of as a positive integrate of perceptions of personal control, a proactive approach to life, and a critical understanding of the socio-political environment, which is rooted firmly in a social action framework that includes community change, capacity building, and collectivity’ (ibid.). Extrapolating these ideas into the context of teaching, we can assume that university teacher personal empowerment may be described as teacher’s gaining power over decisions and resources influencing the quality of teaching practice. Exercising professional choice, university teacher gains an increased control over his work. We believe, however, that the sense of personal empowerment doesn't mean that a teacher has to always be right. It involves a teacher’s readiness to face whatever professional context serves up. Analysis of psychological works on self-empowerment/personal agency allowed us to argue that self-empowerment/personal agency makes people more open, questioning, actively looking for solutions and developing their self-esteem (self-confidence) and self-efficacy (great trust in one’s own abilities). That’s why self-empowerment/personal agency is also considered one of the requisites for personal growth and success, better psychological well-being[44] and one of the factors reducing the stress levels of service employees[18]. Indeed, being self-empowered, teachers know their professional goals and can use their own judgment in achieving them. In other words, self-empowered teachers know they have an active and important role in the educational process and this help them to reduce the number of the stressors they have to cope with and contributes to job satisfaction.As it was mentioned above, personal empowerment involves decision-making. However, the process of decision-making is reported to be directly related to personal autonomy[50] and to teacher autonomy in particular[28]. Meanwhile, lack of participation in decision-making is associated with depersonalization[21] and is regarded as a predictor of burnout syndrome[29]. Having lack of participation in decision-making, teachers become unassertive and feel stressful. Alternatively, according to Miller, Ellis, Zook, and Lyles, participating in decision-making is beneficial for teachers’ well-being and helps them to mitigate stress[39]. These findings imply our hypothesis to be correct. In the context of up-to-date social and economic changes and Russian educational system ambiguity, marked by novelty, complexity, insolubility and lack of structure, teacher’s capacity to make decisions extends its meaning through transformation into ‘decision making under ambiguity’, which implies the ambiguity tolerance (tolerance for ambiguity). Chappelle and Roberts describe the ambiguity tolerance as ‘an individual’s ability to accept ambiguity, lack of structure, complexity, insolubility, etc., … to function rationally and calmly in a situation in which interpretation of all stimuli is not clear’[7: 30]. Some authors associate the ambiguity tolerance with risk taking[13]. The ambiguity tolerance is also seen as an important issue in personal development and is considered to be correlated with creativity and[24]. The latter involves the ability to create one’s own ways of proceeding which is known as constructivism. Meanwhile, constructivism is reported to be linked to personal autonomy[31].This approach makes the ambiguity tolerance extremely important for modern teachers who need experiencing positive emotions even in stressful, ambiguous, problematic situations through transforming them into the challenges for self-development. Teachers who are tolerant of ambiguity seem to be more willing to take risks and open to change. Accordingly, they are ready to accept new information without getting frustrated. As we can see, being tolerant of ambiguity makes the agent to be more autonomous. On this basis, we consider the ambiguity tolerance to be one of the crucial components ensuring teacher professional autonomy. Continuing analyzing teacher personality traits related to perceived teacher autonomy, it’s important to reveal the potential of teacher’s internal locus of control. According to Dormann et al. locus of control involves a belief in oneself relative to one’s environment[12]. People with high internal locus of control believe that their life depends on their choices and actions. They are reported to be able to adopt proactive, problem-solving means to change the environment, and to be more likely to engage in goal-directed activities[19]. On the contrary, individuals with high external locus of control (externals) believe that they can not control what happens to them. Locus of control is reported to be related to job satisfaction[32]. Following the ideas of Deci[9] and Dergacheva[11], we do not consider the term ‘internal locus of control’ to be a synonym to above-mentioned ‘perceived locus of causality’, because ‘internal locus of control doesn’t necessarily involve intrinsic motivation and self-determination’[11: 86]. Based on these ideas, we believe that the presence of internal locus of control is important, but not sufficient to make the teacher act autonomously. As for perceived locus of causality, it is often regarded, as it was mentioned above, as a continuum of perceived autonomy, the highest level of the latter (self-determination) being ensured by intrinsic motivation[48];[49]. Indeed, the concept of‘self-determination’ is often considered as a synonym to ‘personal autonomy’, but the latest research indicates that personal autonomy is often defined as a broader phenomenon[11]; [46]. Drawing on the above mentioned Pearson and Moomaw’s definition of teacher autonomy[46] and taking into account the context of teaching, we assume that perceived university teacher autonomy can be involved in a wider range of processes than self-determination alone. With regard to the above-mentioned and to the context of teaching, the perceived locus of causality seems to be an important teacher personality attribute which can ensure teacher’s perception of work-related autonomy together with some other personality traits and work-related competences. Nowadays, the problem of personal autonomy seems to attract the attention of modern Russian researchers[11]; [22];[25];[26];[33];[36]. Recent Russian works on teacher autonomy, though few in number, consider the phenomenon in a large context of teacher personal development. For instance, Koryakovtseva views teacher autonomy as ‘a requirement for effective personal development and self-actualization’[25: 12]. Sharapkina considers autonomy to be ‘the basis for professional socialization’ and states that ‘its development is one of the top targets of teacher training process’[52: 148]. Based on the above-mentioned ideas and drawing on Leontiev’s psychological theory of personal autonomy[33], this study regards perceived teacher autonomy as the core of ‘freedom to’ as a positive type of freedom. Accordingly, teacher autonomy (1) implies professional interaction, personal development,self-actualization, self-empowerment and work engagement, (2) is ensured by intrinsic motivation to professional achievement and personal development, and a complex of personality attributes (internal locus of control, professional responsibility, creativity) and competences (ability to set goals, ability to make choices, ability to make decisions, pedagogical mindfulness), (3) leads to better performance, job satisfaction, increase of self-esteem and work-related self-efficacy. In this interpretation perceived teacher autonomy is represented as a high-level competency, ensured by a set of teacher personality traits and leading to better performance. Based on the above-mentioned ideas, perceived teacher autonomy may be defined as teacher generic competency, determined by intrinsic motivation to professional achievement and development, professional responsibility, creativity and relative independence from external factors. This competency underlies teacher self-empowerment and successful performance across different teaching-related situations through creating one’s own professional goals, taking intellectual and moral decisions, making free choices, and self-monitoring one’s own professional experience. Thus, an autonomous teacher seems to always be ready to deal with challenges which appear in the changing educational environment. In other words, an autonomous teacher is able to deal with his stress positively through transforming the existing stressors into the factors of his own self-development. Subsequently, for an autonomous teacher teaching generally represents a wide range of experiences and relationships with joy, fascination and satisfaction rather than risks for frustration and disappointment. This viewpoint corresponds with the idea proposed by Priebe and Reininghaus[47] who turn from the negative stress model to an approach that emphasizes the positive sides of work. The authors describe the factors that promote ‘work engagement’, a positive, fulfilling, effective-motivational state of work-related well-being that can be viewed as the antipode of job burnout[2]. The above mentioned ideas are relevant to ‘positive psychology’, a new research and application field that describes aspects of the human condition that ensure human happiness and fulfillment by studying the factors that better one’s life (rather than trying to prevent negative situations)[6];[49];[51]. The proposed approach allows us to reveal the benefits of developing in teachers intrinsic motivation to professional achievement and teacher personal development, together with teacher personality attributes (internal locus of control, professional responsibility, creativity) and work-related competences (ability to set goals, ability to make choices, ability to make decisions, pedagogical mindfulness), ensuring perceived teacher autonomy for prevention of job dissatisfaction and teacher burnout. The model of the conception investigated in this study is shown below in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Conceptual model of the role of perceived university teacher autonomy in preventing of burnout syndrome in university teachers |

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling

- Among the participants of this study there were 81 females (89%) and 10 males (11%), a total of 91 teachers working in Krasnoyarsk State Medical University, Russia. A total of 12 teachers (13%) had 0-five years of experience; 51 teachers (56%) had six-15 years of experience; 28 teachers (31%) had more than 16 years of experience. All these university teachers were invited to participate in this study on a voluntary basis. They were assured that the data collected would only be used for the sole purpose of the study.

3.2. Data Collection Instruments

- Taking into consideration the above-mentioned conception, the method of ‘Psychological well-being Scale’, adapted from the Russian version of the questionnaire ‘The scales of psychological wellbeing’ of Ryff[51], and the method of Dergacheva[11], based on Deci and Ryan’s General Causality Orientations Scale[10], we elaborated a qualitative, descriptive type multiple-choice questionnaire, which was obviously the most suitable tool for gathering data in the context of University teacher professional activity. The questionnaire was distributed with the purpose to elicit participants’ responses and views on the level of perceived autonomy they have / would like to have. The content of this questionnaire, containing eleven items each of 10-17 statements for the assessment of the level of perceived teacher autonomy, was based on the recent scientific works on autonomy. At the same time, the authors’ experience in teaching in Russian universities was taken into consideration to ensure internal content validity. The questionnaire was duly validated by experts in the field of higher education. The reviewers were asked to estimate the content of the questionnaire as well as the form of questions presentation. After validation, some items were revised as per the suggestions of the experts, some were ignored and some new ones were included. In this questionnaire, the level of autonomy was measured by estimating the type of teacher motivation, teacher personality traits (internal locus of control, professional responsibility, creativity) and competences (ability to set goals, ability to make decisions, ability to make choices, pedagogical mindfulness), as well as specific work incentives and disincentives of the university educational area, ensuring teacher’s perception of professional autonomy. Most of the questions employed a four-point scale for participants to indicate their answers (1-yes, often, 2-yes, sometimes, 3-rarely, 4-no - for the questions that reflected the participants’ professional behaviours; 1- yes, absolutely / strongly agree, 2- yes, to a certain point / tend to agree, 3- not really / tend to disagree, 3- certainly not - for the questions that were directed to reveal the participants’ attitudes and work-related personality traits). Procedures for teacher burnout measurement included two types of instruments. Firstly, studying the level of burnout of university teachers as a diagnostic tool we have used the Method of diagnosing of emotional burnout level of Boiko[4]. Burnout symptoms and levels as well as phases of burnout development (stress (or alarm reaction), resistance, and exhaustion) were diagnosed with the use of this method. Burnout symptoms and levels as well as phases of burnout development (stress, resistance, and exhaustion) were diagnosed with the use of this method. The received results allowed us to divide the sampled population into three groups: the first group comprised the respondents who had a completely developed burnout syndrome in any of three phases (that is total score in one of the phases was greater than or equal to 61 points); the second group included the respondents who had a formation stage of the syndrome in any of three phases (that is total score in one of the phases made greater than 37 and less than 60 points); the third group was composed by the respondents who did not develop the syndrome (i.e. total score exceeded 36 points in none of the phases). Secondly, a questionnaire was distributed with the purpose to elicit participants’ responses and views on this disorder. It employed a six-point scale for participants to indicate their responses and views on teacher burnout problem (6-strongly agree, 5-agree, 4-tend to agree, 3-tend to disagree, 2-disagree and 1- strongly disagree). The results received after the use of the questionnaire, were correlated with the data, received from the use of the psychological method of Boiko[4] estimating the level of teacher burnout. Finally, the results received from the procedures for teacher burnout measurement, were analyzed and correlated with the data received from the questionnaire estimating the level of teacher autonomy.

4. Results and Their Discussion

- According to the results of the Method of diagnosing of emotional burnout level of Boiko[4], the first group (with a completely developed burnout syndrome) comprised 21 respondents (23% of the sampled population); the second group (with a formation stage of the syndrome in any of three phases) - included 34 persons, which made 37% of the sampled population; the third group (the syndrome is not developed) was composed by 36 persons (40% of the sampled population). The results of a survey on teacher burnout showed that more than 73 per cent out of 91 University teachers-respondents found teaching stressful. They also reported that the main sources of stress and burnout syndrome are: too much clerical work (76% common variance), teaching work overload (72% common variance), social demands (36% common variance), self-development demands (25% common variance), lack of autonomy (32% common variance), disrespect and loss of status of the teaching profession (22% common variance). About 57 per cent of the respondents admitted having two or more burnout symptoms.As for perceived teacher autonomy, according to our research results, perceived teacher autonomy was positively related with professional self-development and self-actualization in 69%, 84% and 91% of responses correspondingly. On the contrary, a negative correlation was revealed between teacher autonomy and such external factors as material conditions (lack of multimedia equipment, funding cuts, lack of material) (21%), obligation to conform to a much too constraining programme (20%), too much clerical work (45% common variance), obligation to reach or increase a given rate (success rate for a degree, employability) (58%), teaching work overload (49% common variance), size of groups (9%) as well as a lot of useless software work, low salary, bureaucracy, beadledom (16%).About 90 % of teachers who demonstrated trouble in coping with work-related stressors (teachers with completely developed burnout syndrome in any of three phases) turned to have low level of autonomy. As for teachers with a formation stage of the syndrome in any of three phases, 85 % of the respondents turned to have moderate level of autonomy, 10 % demonstrated law level of autonomy and only 5 % turned to have high level of autonomy. About 87 % of teachers from the third group (without burnout syndrome) demonstrated high level of autonomy. Most of teachers who were selected and admitted being autonomous didn’t report about relation of teaching work overload, a high volume of clerical work or other factors providing stress and burnout with teacher autonomy. Positive relationships with students and colleagues and the challenges of the work have been reported by autonomous teachers as the most enjoyable aspects of teaching. And this is of great importance, for based on these findings, we can suggest that in cases of teaching and clerical work overload and other reported sources of stress teacher autonomy will allow teachers to deal with their stress positively (e.g., as an extra stimulant to reconsider and develop one's teaching practice). Hence, perceived teacher autonomy should be viewed as an important element in preventing teacher burnout syndrome. For most of the respondents, statistically significant negative relationship was found between professional autonomy and teacher burnout syndrome (p < 0.05). Low level of teacher autonomy correlated with the development of burnout syndrome. The results of our study suggest that personality traits which correlated with low burnout rate in university teachers included internal locus of control, self-empowerment (or personal agency), responsibility, ability to set goals and make decisions, teaching achievement motivation. On the grounds of our research, one may assume that the complex of above mentioned teacher-related personality factors correlate with high and middle levels of autonomy.Continuing to analyze the results of our investigation, an explanation should be provided about the imbalance in sampling that we had. Firstly, it should be said that the choice of male to female ratio was determined by the actual situation in Russian universities, where most of teachers are women. Secondly, analyzing our study results, we revealed no significant difference in gender (p > 0.05), which allowed us to interpret the received data in the whole. The proposed approach, on the one part, makes our findings more relevant for the Russian context, and, on the other part, contains the risk of possible gender bias and causes a limitation for our study outcomes’ application in the other cultural contexts. However, in spite of the above-mentioned limitation, we can assume that in the context of Russian higher education our empirical study outcomes supported our hypothesis that the levels of teacher autonomy and teacher burnout rate were interrelated. More specifically, perceived teacher autonomy seems to be negatively associated with teacher’s feeling of professional burnout. Lack of autonomy can make teachers not to meet the demands placed upon them as they may not be capable to make important decisions critical to task accomplishment. And controversially, high level of perceived autonomy seems to help teachers to make such decisions. All this allows us to suggest that, being a specific work-related teacher personality characteristic, perceived teacher autonomy should be taken into account to prevent university teacher burnout.

5. Conclusions

- In the previous sections, we have constructed a formal specification that identifies and characterizes the notions of autonomy and burnout. The main purpose of this study was to determine whether the improvement in the degree of perceived teacher autonomy reduces the degree of perceived burnout in Russian university teachers. This goal was achieved by surveying a sample of teachers from Krasnoyarsk State Medical University. These teachers’ perceptions and judgments are the basis of our overall findings that the degree of reduction in job burnout is associated with the improvement in the degree of perceived teacher autonomy.In the paper we showed that being recognized as one of the criteria of psychological well-being and mental health of a person, a high level of perceived teacher autonomy can mitigate university teachers’ stress and reduce experience of burnout by stimulating teacher professional efficacy, personal growth and development. the results of our investigation showed that deficiency of perceived teacher autonomy can be regarded as a signal of possible trouble and lead to burnout. It is expedient to suggest that perceived teacher autonomy plays a crucial role in providing a new type of higher education by allowing pedagogical research, teacher influence on school policies, effective implementation of new educational technology, teacher development and self-actualization in a broad sociocultural context, preventing university teachers’ burnout and retaining teachers in their jobs.At the same time, the imbalance in sampling and a specific context of our investigation cause an objective limitation for the application of our empirical study outcomes in the other contexts and require a more detailed study of the relations of perceived autonomy and burnout syndrome in university teachers. We also hope this work will set the stage for research initiatives investigating in a systematic manner the conditions and behavioral and developmental consequences of developing perceived teacher autonomy. Specifically, future studies may concern relations of perceived teacher autonomy and reusable skills, self-organization developmental trajectories and open-ended teacher development.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors are grateful to all colleagues who took part in the study, in particular the professors and instructors of the Department of Latin and Foreign Languages and the Department of Psychology and Pedagogics of the State Medical University of Krasnoyarsk.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML