-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2013; 3(3): 45-51

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20130303.03

Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Well-being: Preliminary Results

Mª Celeste Dávila1, Marcia A. Finkelstein2

1Social Psychology Department, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, 28223, Spain

2Psychology Department, University of South Florida, Tampa, 33620, Florida

Correspondence to: Mª Celeste Dávila, Social Psychology Department, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, 28223, Spain.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The purpose of this work was to study the relationship between prosocial behaviour and well-being, specifically to examine the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior, citizenship motives, perceptions of organizational citizenship behavior as in- vs. extra-role and employee well-being. A total of 144 people at 17 educational companies completed surveys measuring the above constructs. Both organizational citizenship behavior and its motives were associated with well-being, with altruistic motives showing a stronger correlation than egoistic motives. The perception of OCB as in-role was also related with well-being. The results are discussed based on previous evidence.

Keywords: Prosocial Behavior, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, Motives, Psychological Well-Being, Subjective Well-Being

Cite this paper: Mª Celeste Dávila, Marcia A. Finkelstein, Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Well-being: Preliminary Results, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 3 No. 3, 2013, pp. 45-51. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20130303.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Prosocial behaviors are actions aimed at protecting or increasing the welfare of others (e.g.,[1]). Within this category of behaviors are myriad activities including, for example, volunteerism, emergency aid, and blood donation. Many prosocial behaviors are directed at individuals, but social groups or organizations also can serve as beneficiaries[2]. Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) is one type of prosocial behavior that provides benefits to organizations and their employees[3]. OCB encompasses employee activities that exceed the formal job requirements and contribute to the effective functioning of the organization[4]. While citizenship behaviors have been categorized in a multitude of ways (e.g.,[5],[6]), one popular conceptualization proposes two dimensions differentiated according to the intended target of the behavior ([3],[7]): 1. OCB aimed at individuals (OCBI). These are citizenship activities directed at specific people and/or groups within the organization. The help can be work-related, such assisting a colleague with a specific task. Alternatively, it may be unrelated to the job, for example helping a co-worker with a personal problem. 2. OCB aimed at the organization (OCBO). Such behavior might include offering ideas to improve the organization’s functioning.While little studied with regard to OCB, well-being frequently is cast as an important antecedent of prosocial activity. Well-being has been studied from two perspectives: subjective and psychological. Subjective well-being includes life satisfaction and emotional responses in the form of positive and negative affect[8]. Life satisfaction is a cognitive evaluation of the quality of one’s overall life experience[9]. Positive affect refers to the extent to which a person feels enthusiastic, active and alert, while negative affect encompasses distress or displeasure[10]. Both can be operationalized either as a generalized affect or a more immediate or daily mood.In general, individuals in a positive mood are more likely to help than those in a negative or neutral mood[11]. Experiences that improve mood precede helping behaviors. For example, pleasant aromas promote prosocial behavior even in the absence of a direct request for help[12]. Well-being also has been shown to be a consequence of prosocial behavior.[13] found that employees who participated in corporate volunteering more frequently reaped benefits in the form of higher self-esteem and life satisfaction. In a longitudinal study,[14] found that there was a reciprocal causal relationship between life satisfaction and volunteerism.Psychological well-being refers to the development of one’s potential and comprises a number of dimensions[15]: self-acceptance (positive evaluation of oneself and one’s past), personal growth (a sense of sustained growth and development), purpose (the belief that life is meaningful), positive relations with others, environmental mastery (the capacity to effectively manage one’s life), and autonomy or self-determination.With regard to the workplace, job engagement as an indicator of psychological well-being ([16]; but see[17]). Job engagement refers to a positive mental state of fulfilment in one’s work and is characterized by high levels of energy and mental resilience with regard to the job and by the desire to make an effort even in the presence of difficulties. The engaged employee shows high job involvement and feelings of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, pride and challenge in the work. Also present is a total concentration on one’s responsibilities such that time passes quickly, and disconnecting from the job is difficult[18]. Aspects of psychological well-being such as environmental mastery are contained in the engagement construct (e.g.,[15]). The present work broadened the study of prosocial activity by investigating the relationship between well-being and OCB. Volunteerism and OCB share important attributes: Both are deliberate and discretionary behaviors that take place in an organizational context and benefit non-intimate others. Rather than transitory responses to specific situations, the two occur over extended periods of time. Although OCB, unlike volunteerism, is carried out by employees whose regular service is paid by the organization, citizenship behavior is not subject to the formal payment system of the organization ([19],[20]). Based on these similarities, it is expected that OCB, like volunteerism, is associated with the experience of well-being. Prior investigations show that employees in a positive mood are more likely to peform extra-role behaviors at work ([21],[22],[23],[24],[25]). The relationship between positive affect and citizenship activities is particularly strong for OCBI ([26],[27],[28],[29]). Presumably, individuals in a positive mood feel more attracted to others and thus are more likely to assist them. Additionally, helping can be self-rewarding, allowing one to maintain his or her positive affect[30] and directing the helper’s attention away from any negativity[31].Self-Determination Theory[32] proposes that autonomous vs. controlled prosocial behaviors have very different effects on the individual. When behaviors have an external locus of causality, that is, when people do not feel "ownership" of their actions, autonomy is undermined, reducing well-being. Maintaining autonomy in prosocial activity boosts well-being in the form of positive affect, vitality and self-esteem[33]. In relation to perception of autonomy of behavior, one persistent question in research on OCB is whether employees in fact perceive the activity as extra-role. Often the boundary between OCB and formal role behavior is not clear and varies among employees and supervisors ([34],[35]). Workers with high affective commitment are more likely to define their responsibilities more widely and thus engage in OCB because they view it as part of their duties. Supervisors both deliberately and unconsciously assess OCB and reward citizenship with promotions, increases in salary, etc. ([36],[37],[38],[39],[40],[41],[42]). One’s motives for engaging in OCB may affect the relationship between citizenship behavior and well-being. People perform citizenship behaviors for disparate reasons, with the same activity serving different psychological functions for different individuals[43].[20] identified three classes of motives for OCB. Two are relatively altruistic: organizational concern (OC) or respect for organization and a sense of pride and commitment to it; and prosocial values (PV), the desire to help others and be accepted by them. In contrast, impression management (IM) motives are egoistic. They involve a desire to be perceived as friendly or helpful in order to obtain specific benefits. That motives can vary so widely suggests that OCB may have varying effects on the well-being of those who engage in citizenship behavior. For example, those who seek to fulfil altruistic motives may experience more well-being than those whose OCB is driven by more selfish objectives. The potential difference in well-being is suggested by recent research examining the degree of autonomy or volition employees experience in performing citizenship activities. At one end of this “autonomy continuum” is self-motivation, in which the employee’s actions are experienced as congruent with the self. They are consistent with the individual’s values and interests and reflect an internal locus of causality. In contrast, controlled behaviors do not reflect an expression of values. Such behaviors may arise from self-imposed pressures, such as feelings of guilt, or from external controls. The aim may be to maintain self-esteem, please others, or comply with certain external demands ([32],[44]). The altruistic PV and OC motives are considered autonomous, an expression of underlying values, while the self-focused IM motives are more controlled[33].The present study examined the relationship between OCB, OCB motive, perception of citizenship as in-role, and employee well-being. For all hypotheses, we use the same indicators of subjective and psychological well-being. For subjective well-being, these are positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction. Hypothesis 1 addresses the relationship between OCB and well-being. Hypothesis 1a stems from the observation of a relationship between prosocial behavior and such indices of well-being as positive affect and life satisfaction. For example,[11] found that individuals in a positive mood are more likely to help others than those in a negative or neutral mood.[13] and[14] described a positive relationship between volunteerism and life satisfaction. And[21] showed that employees in a positive mood were more likely to peform extra-role behaviors at work. Hypothesis 1a. OCB will be positively associated with positive affect, life satisfaction, and job engagement and negatively related to negative affect. Hypothesis 1b is based on the finding that OCBI was more strongly related than OCBO to affective variables ([27],[28],[29]). Those in a positive mood felt more attracted to other individuals and thus are expected to be more likely to assist them than the organization per se.Hypothesis 1b. OCBI will have a greater association than OCBO with the above measures of subjective and psychological well-being.According to self-determination theory, people experience greater autonomy when they perceive their behaviors as freely chosen. When people do not feel ownership of their actions, the experience of well-being declines. We expect that whether employees view OCB as truly discretionary will impact feelings of well-being. Hypothesis 2. The perception of OCB as in-role will show a negative correlation with positive affect, life satisfaction, and job engagement and a positive correlation with negative affect. Self-determination theory also proposes that altruistic motives for helping generally are more autonomous than egoistic motives[33]. In a longitudinal study,[45] found that individuals who engaged in OCB because they were prosocially motivated subsequently experienced higher levels of positive affect. Hypothesis 3 examines the effect of this difference on well-being. Hypothesis 3. OC and PV motives will have a greater association than IM motives with all measures of psychological and subjective well-being.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- Participants were 144 Spanish employees from 17 companies dedicated to early childhood education and primary education. Their mean age was 36.19 (SD = 10.31), and 71.8% were women. With regard to educational level, 1.4% had primary school education, 10.4% secondary or high school education, and 87.5% had earned a college degree. They were employed in their companies between 1 month and 32 years (M = 86.43 months, SD = 99.92 months), and the majority worked full-time (91%). Respondents performed teaching jobs.

2.2. Instruments

- Participants completed a questionnaire containing the following measures:OCB. We used the[27] instrument adapted to a Spanish population[46] to measure OCBO and OCBI. The scale comprises 16 items and utilizes a 5-point Likert type response format ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Coefficient alphas were 0.79 (OCBO) and 0.77 (OCBI). Often studies of OCB augment self-report data with information from co-workers or supervisors. However, we were less concerned with obtaining an objective accounting of OCB than with assessing people’s perceptions of their behavior. Effectively encouraging OCB requires understanding an individual’s views of his or her behavior and the underlying motivations.In-role/extra-role perception of OCB.[27]’s (2002) scale also was used to assess the extent to which participants viewed OCB as in-role activity. Respondents reviewed each item and indicated the degree to which they perceived each behavior as part of the job. Response alternatives ranged from 1 (it is an extra-role behavior) to 5 (it is an in-role behavior). Coefficient alpha was 0.93. OCB motives. Motives were measured with the scale used by[7] adapted to Spanish population[46]. The 30-item instrument measures PV, OC, and IM motives with a 5-point Likert type response format that ranges from 1 (not at all important) to 5 (extremely important). Coefficient alphas were 0.91 (OC), 0.86 (PV) and 0.91 (IM). Subjective well-being. Three dimensions of subjective well-being were measured: positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction. Positive and negative affect were evaluated using a Spanish adaptation of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule[10]. The scale that was used assesses generalized affect rather than a momentary mood. The instrument consists of 20 items that assess feelings or emotions that one may experience. Ten items refer to positive emotions and 10 to negative emotions. Response options used a 5-point Likert format ranging from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). Coefficient alphas were 0.77 for both positive and negative affect. Life satisfaction was assessed with the 5-item scale of[47] adapted to Spanish by[48]. Response options ranged from 1 (absolutely disagree) to 5 (absolutely agree). Coefficient alpha was 0.84. Job engagement was evaluated with the reduced version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale developed and adapted to Spanish by[49]. The scale comprises 9 items with a Likert-type response format ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Coefficient alpha was 0.87.

2.3. Procedure

- Two data collection procedures were followed. Respondents were given the option of completing the questionnaire on paper, with an employee of the organization distributing the questionnaires and collecting the completed surveys. Alternatively, participants could access the questionnaire on the Internet via a link sent by the organization to its employees. Participation was voluntary, and employees were informed that their data would be kept confidential so as to ensure anonymity.

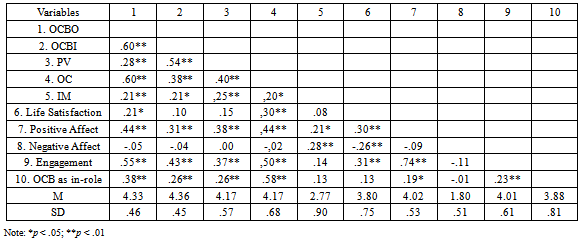

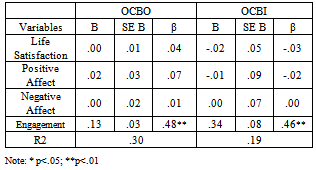

3. Results

|

|

4. Conclusions

- The present work examined the extent to which OCB, citizenship motives, and the perception of citizenship activities as in-role were associated with well-being. Both OCBO and OCBI were associated with subjective well-being in the form of positive affect and with job engagement in relation to psychological well-being. But only job engagement was a significant predictor of OCBO and OCBI. In this sense, psychological well-being seems to have a more decisive role in the development of citizenship behaviors.The lack of association between OCB and negative affect was consistent with prior work (e.g.,[30],[26]) and may in part be attributable to the measures used in this study. Lee & Allen[27] found that specific negative emotions, rather than a general negative affect, explained some instances of OCB. Contrary to expectations, the data showed no significant differences between the two types of OCB and either positive affect or job engagement. Moreover, it was found that job engagement accounted for a greater proportion of variance in OCBO than in OCBI.Surprisingly, well-being (in particular, positive affect and job engagement) was positively correlated with the view of OCB as in-role. Perhaps the act of engaging in OCB produces a positive affect which in turn causes an employee to incorporate citizenship as part of the job (e.g.,[50]). Our focus here was on dispositional more than organizational variables. A complete understanding of the citizenship dynamic also must consider characteristics of the organization and the interaction of the individual with the organization. For example, affective organizational commitment or organizational identification may explain why carrying out one’s duties may engender positive feelings. As hypothesized, OCB motives, in particular regard for the organization, also were related to well-being. Only the self-focused IM motives were associated with negative affect. Taking on extra work in hopes of achieving personal benefits may generate anxiety or hostility, perhaps in part from a recognition that one is not as altruistic as is socially desirable. According to self-determination theory, when behaviors have an external locus of causality (therefore, they are not based on personal values), autonomy is undermined, and this reduces feelings of well-being (e.g.,[33]). Curiously, only OCBO and OC motives were related to life satisfaction. A potential explanation would be the importance of belonging to social groups or other social systems to people, that is, the sense of feeling involved in them.[51] described the belonging as a basic human need.[52] described sense of belonging as an important element for mental health and social wellbeing. In this sense, behaviors and motivations that would satisfy the need of belonging may promote the well-being. Despite this, life satisfaction was not a significant predictor of OCBO. Possibly covariance between variables analyzed inflated the observed relationships between OCBO and life satisfaction. The study’s cross-sectional design precludes conclusions about causal relationships. Some have suggested that well-being, specifically positive affect, leads to OCB[27]. Alternatively, the reverse also may be true, with the act of helping contributing to the experience of well-being.Another limitation was the nature of the respondents’ jobs. Many were teachers, an occupation requiring a high level of education. However, studies of OCB traditionally use lower-level employees because job descriptions for more professional positions often are less specific, making it difficult to distinguish between formal responsibilities and OCB[53]. Thus generalizing the present findings to other types of employees may pose difficulties[54]. Additionally, the relatively small sample size may have contributed to underestimating the influence of some variables. Future studies will explore the influence of demographic variables such as age, gender, and longevity in the job also will be explored. Employees with a long organizational tenure are likely define their responsibilities more broadly[34]. Educational level will also be examined, as similarly, education is positively associated with social responsibility[29]. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment also affect employees’ views of what constitutes in-role vs. extra-role behavior[34]. Additionally, we are asking whether in- vs. extra-role perceptions of OCB moderate the relationships between OCB, motive, and well-being.In summary, OCB, and particularly altruistically motivated OCB, is associated with positive feelings. Although the influence of in- vs. extra-role perceptions of OCB requires additional study, the data do not support the idea that viewing citizenship as part of one’s job interferes with feelings of well-being.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML