-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2013; 3(2): 25-30

doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20130302.01

Family Closeness, Social Physique Anxiety and Sexual Coercion as Determinants of Academic Self-Efficacy among Female Undergraduate Students in a Nigerian University

Florence Ngozi Ugoji

Department of Guidance and Counselling, Delta State University. P.M.B. 1, Abraka

Correspondence to: Florence Ngozi Ugoji, Department of Guidance and Counselling, Delta State University. P.M.B. 1, Abraka.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The study investigated the perceived effects of family closeness, social physique anxiety and sexual coercion on academic self-efficacy among female undergraduate students in Delta State University, Abraka. A descriptive survey design was adopted for the study.350 female undergraduate students were selected from the population of female students in Delta State University, Abraka .Two research questions was raised in the study. They are “Are there significant relationship between family closeness, social physique anxiety, sexual coercion and academic self-efficacy of female undergraduates? And what are the significant composite effects of family closeness, social physique anxiety, sexual coercion and academic self-efficacy female undergraduates? Four standardized instruments measuring the independent variables and the criterion measure was administered to the participants. Data were analysed using Pearson Product Moment Correlation and the Multiple Regression statistics. The results indicate that all the variables were significant, with the strongest relationship being between family closeness and academic self efficacy while those of social physique anxiety and academic self-efficacy, sexual coercion and academic self-efficacy were all negative. The three independent variables accounted for 37.2% of the total variance of academic self efficacy with family closeness being the most potent. Therefore, it is recommended that family bonding associative activities should be encouraged. In addition academic self-efficacy training programmes should be included in orientation programmes and curriculum of the students.

Keywords: Family Closeness, Social Physique Anxiety, Sexual Coercion, Academic Self-Efficacy, Female Students, Determinants

Cite this paper: Florence Ngozi Ugoji, Family Closeness, Social Physique Anxiety and Sexual Coercion as Determinants of Academic Self-Efficacy among Female Undergraduate Students in a Nigerian University, International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 25-30. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20130302.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- One positive predictor of student’s persistence in academic task identified by researchers is academic self-efficacy. It has frequently been cited as an important component in academic success[6];[27];[20];[26];[34]. No academic Self-efficacy could parsimoniously be defined as an individual’s judgments of their capabilities to organize and execute courses of action required to attain designated types of academic performances. First proposed by[3], self-efficacy has been seen as a construct, which aids understanding of human behavior and motivation. He underscored the importance of this construct explaining that, efficacy expectations determine how much effort people will expend and how long they will persist in the face of obstacles and aversive experiences. Researchers subsequently examined how academic self-efficacy applies to scholastic activities[10];[25]. These studies have demonstrated that individuals with stronger self-efficacy beliefs in specific content areas perform better in those specific areas. With particular relevance to counseling psychology, there are specific areas in which higher levels of academic self-efficacy have been linked to better performance. These areas include academic self-efficacy and college student satisfaction[10] academic self-efficacy and study skills acquisition[35] math and science self-efficacy[23]. The implication is that self-efficacy appears to have a relationship to persistence in completing educational programme. Thus, Logic would suggest that improving a student’s beliefs in her/his ability to succeed in school could potentially contribute to improvement in academic achievement and persistence in academic activities.However, in Nigeria it has been reported that there is increasing poor academic achievement and lower academic standard is a common occurrence among educational institutions. Pertinent to this observation is that more female students in tertiary institutions are faced with academic difficulties in their pursuit of postsecondary education. The consequence of lower educational attainment among female students are decreased opportunities for careers and earning potential, engaging in anti-intellectual activities, leaving school and such social vices such as prostitution. While academic self-efficacy has been identified as a likely factor in academic functioning, how family closeness and the sexuality of female students could impinge on efficacy development has received little or no attention. There is currently a dearth of information on how sexuality components such as social physique anxiety and sexual coercion could influence academic self-efficacy. The ability to measure and describe potential effects in these areas could aid teachers, counsellors, and administrators to appropriately intervene to improve academic self-efficacy of female undergraduate students.For instance, a number of studies have emphasized the problems of people participating in physical activities’ based on motivational factors enshrined in social physique anxiety. These include having a better, more healthy life, pursuing the attainment of attractiveness, losing weight, gaining social support and acceptance, as well as creating social opportunities, No[6];[16];[33]. Social physique anxiety” is an anxiety created when people feel unsatisfied with their bodies and they worry about negative feedback from others[27].[17] introduced the concept of social physique anxiety to represent the anxiety rather than the bodily concerns related to a person’s ability to achieve specific physical behavior and present the expected body image.[9] found out that most girls create unrealistic goals to achieve their ideal body images. However, when they are dissatisfied with their body shapes, they choose not to participate in school work. In other words, the perception of a high-level of social physique anxiety among female undergraduate will decreases their participation in academic work, leaving their aspirations unfulfilled. Thus, it could be said that social physique anxiety concerns identity and is a potential barrier to personal participation in academic task. Significantly, the relationship between social physique anxiety and academic self efficacy is expected to be inversely mutual to each other.Sexual coercion refers to acts of using pressure, alcohol or drugs, or force to have sexual contact with someone against his or her will. Popularly associated with violence against women, it is also perceived as tactics of post refusal sexual persistence with someone who has already refused[31]. Sexual coercion is in the continuum for sexually aggressive behaviour. This continuum includes many harmful and aggressive acts such as rape, sexual abuse and sexual assault. There is increased recognition of the links between coercive sex and adverse reproductive health outcomes including; unintended pregnancy, non-use of contraception, unsafe abortion, gynecological morbidity and HIV/AIDS[18]. With the prevailing sexually victimizing conditions faced by many female undergraduates in Nigeria[1] the potential for exposure to sexual coercion as well appears to be inevitable. Sexual coercion may disturb female students’ academic performance as the memories may come as flashbacks, feelings of sexual regression and disturbed emotions during school hours[31]. This may have an adverse effect on the individuals’ belief of performing adequately in an academic task.Few researchers have examined the role of the family in context with fostering or impeding the development of academic self efficacy. Numerous studies have supported the notion that, across cultures, humans have an innate need and drive for forming and maintaining intimate relationships[4]. For many, this quest for closeness is played out through reunion with familiar members, peers, coupling with another person in a committed relationship, often marriage. Obviously, young people spend a great deal of time thinking about, talking about, and being in romantic relationships[13]. Though peers exert great influence on adolescents, the family remains an important factor to their development, but not limited to academic performance[11];[12];[22], school adjustment[2];[5];[7], and life stress[30].Hence, family closeness is important to children's development and has long been proved in family system studies. For example, many children from divorced families were found to have more behavioral problems, less social competence, more psychological suffering, and less surplus learning, compared to those children from intact families[14];[15];[29]. Lu & Hung,[28] postulated that mothers who provided an emotionally warm home climate fostered competent first-grade outcome for girls. Other scholar also investigated how different level of family closeness related to adolescent delinquencies[8].[19] suggested that college students reporting generally secure attachment relationships also indicate high scores in family relationships. In addition, attachment theory also has cross-cultural validity[19];[32], No research regarding how family closeness affects self-efficacy is sparse and limited.

2. Research Questions

- The following research questions were raised in the study;1) Is there significant relationship between family closeness, social physique anxiety, sexual coercion and academic self-efficacy of female undergraduates?2) What are the significant composite effects of family closeness, social physique anxiety, sexual coercion and academic self-efficacy female undergraduates?

3. Research Design

- This study applied the descriptive survey method.

4. Population and Sample

- The population of the study consisted of all female undergraduate students in Delta State University, Abraka, Nigeria. Through a simple random sampling technique, a total of 350 female undergraduate students were selected from the population of female students in Delta State University, Abraka, Nigeria. The participants’ age ranged from 19 to 27, with a mean age of 22.7 years.

5. Research Instrument

- The research tool used for the study was a multi-choice questionnaire, consisting of five sections (sections A, B, C, D, and E). Section A consists of attributive data such as, age and gender. Section B, C, D, and E consist of standardized instruments measuring the independent variables and the criterion measure.

5.1. Social Physique Anxiety Scale

- The questionnaire administered was the Social Physique Anxiety Scale[SPAS], developed by[17]. The SPAS is a 12- item self- report scale, which assessed the degree of anxiety an individual experienced as a result of perceived observation or evaluation of his or her physique. The items were presented on a 5-point Likert-type scale, and respondents indicated the degree to which the statements were characteristic or true of them (not at all, slightly, moderately, very, and extremely). The items were summed for a total social physique anxiety score that can range from 12 (low SPAS) to 60 (high SPAS)[17]. The SPAS demonstrated adequate internal consistency and test-retest reliability over an 8-week period with adult female populations. Construct and criterion-related validity for the SPAS has also been demonstrated as well as internal consistency[17]. For the purpose of this study the scale has demonstrated a reliability coefficient of 0.87.

5.2. Family Closeness

- The family closeness scale was adapted from the Love Schemas Scale. The measure contains six subscales that describe each of the schemas: secure, clingy, skittish, fickle, casual and uninterested. It is representative of respondents’ own feelings and experiences. The first three items, secure, clingy and skittish, were taken directly from the Adult Attachment Questionnaire and they represent the attachment styles of desire to be close. Typical items in the scale were “I am comfortable with closeness and/or independence” “I find it easy to get close to others.” Respondents rate their level of agreement for each of the items on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from, "Never true of me" to "Always true of me”. After pilot testing the scale reported a 0.76 reliability coefficient.

5.3. Sexual Coercion

- The sexual Experiences scale measures sexual coercion. The SES uses a dichotomous response format of Yes or No to 10 items. Participants are classified according to the most severe self-reported sexual victimization. The classifications are (a) no sexual aggression, (b) sexual contact, (c) sexual coercion, (d) at- tempted rape, and (e) rape. The higher the classification, the higher the sexual victimization. The reported internal reliability for women was .74 and test–retest agreement after 1 week was 93%. The Cronbach’s alpha was .85.

5.4. Academic Self Efficacy Scale

- The scale is an adapted version of the ten (10)-item version of self-efficacy measure developed and validated by Schwarzer and Jerusalem. The scale has high proficiency in determining the individual’s level of self-efficacy. The scale is not only parsimonious and reliable, it has also be proven valid in terms of convergent and discriminate validity. It has been used in numerous research projects, where it typically yielded internal consistencies between alpha = .75 and .91.

6. Procedure for Data Collection

- Participants were informed of the confidentiality of the process as well as guided on how to fill the questionnaires. The entire process was conducted in 12days.

7. Data Analysis

- Relationship between the independent variables and academic self efficacy was analyzed using Pearson Product Moment Correlation and the Multiple Regression statistics.

8. Results

8.1. Research Question 1

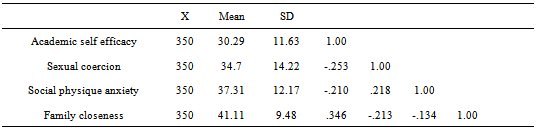

- Are there significant relationship between family closeness, social physique anxiety, sexual coercion and academic self-efficacy of female undergraduates?

|

|

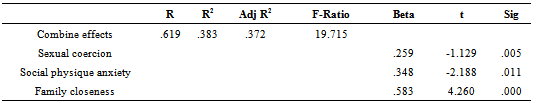

8.2. Research Question 2

- What are the composite effects of family closeness, social physique anxiety, sexual coercion and academic self efficacy?From the results presented in Table 2, the independent variables collectively yielded a coefficient of multiple regressions (R) of .619 and an adjusted R2 of .383 and an adjusted R2 of .372. This shows that 37.2% of the total variance of academic self efficacy of the participants is accounted for by the combination of the three predictive variables studied. The analysis of variance produced an F- ratio value significant at 0.05 level (F = 19.715; p < .05). The findings thus confirm that the four variables were significant predictors of the criterion measure and that this prediction could not be by chance.

9. Discussion

- The analysis of relationship between family closeness, social physique anxiety, sexual coercion and academic self-efficacy of female undergraduates indicates that the correlation coefficients between all the variables were significant. However, the strongest relationship found was between family closeness and academic self-efficacy, while those of social physique anxiety and academic self-efficacy, sexual coercion and academic self-efficacy were negative. This suggests that family closeness, social physique anxiety and sexual coercion could influence academic self-efficacy of female undergraduates.The multiple regression analysis in Table 2 shows that family closeness, social physique anxiety and sexual coercion could predict academic self-efficacy female undergraduates. The magnitude of this relationship in predicting academic self-efficacy among female undergraduates is reflected in the values of coefficient of multiple regressions (R) of .619 and an adjusted R2 of .383 and an adjusted R2 of .372. Thus, it can be said that 37.2% of the total variance of academic self-efficacy of the participants is accounted for by the combination of family closeness, social physique anxiety and sexual coercion. Consequently, the other 62.8% variation of academic self-efficacy could be attributed to factors not included in this study. The F-ratio value of 19.715 significant at 0.05 further affirms this posit that the predictive capacity of the independent variables could not have be attributed to chance factor.With regard to the extent to which each of the three independent variables contributes to the prediction, it could be ascertained that family closeness is the most potent predictor of academic self-efficacy among the other factors. This is in congruence with the related studies of previous researchers[29],[32];[19]. It should be noted that the Eriksonian theorization holds that female identify and enhance self-image at this stage of life via socializing. Thus, it becomes obvious that a positive relationship with particularly the family may become essential in the development of beliefs in self and even academic delivery. Evidently, family closeness could be a primary phenomenon heightening the engagement in successful academic activities.[28] postulated that mothers who provided an emotionally warm home climate fostered competent first-grade outcome for girls. Further,[19] suggested that college students reporting generally secure attachment relationships also indicate high scores in family relationships. The quality of family relationships can have long lasting effects on the worth placed on self and further shape other personal values Social physique anxiety is the next potent predictor of academic self-efficacy in this study. The current finding is similar to prior studies[6];[16];[33];[27];[17];[9] which indicated that the anxiety related to a person’s ability to achieve specific physical behavior and present the expected body image is vital in determining their academic delivery. Therefore, when female undergraduates could not confirm the possibility of success from presenting positive body image, they could fell higher levels of anxiety, which could obstruct not only their participation in physical activities but as well their academic belief and certainty.Sexual coercion is another significant predictor of academic self efficacy among female undergraduates. That this factor determine academic self efficacy is rooted in the relationship between fellow students and university staffs. It was earlier noted that sexual coercion is in the continuum including many harmful and aggressive acts such as rape, sexual abuse and sexual assault. There are obvious undocumented reports of sexual harassment and victimization among females undergraduates either for scores, threats or blackmail from staffs and students. The preponderance of such activities could influence levels of interest and commitment to academic activities among these females. Hence, their belief in their capabilities to perform defined academic task may depend on the hazardous overtures of sexual coercion around them. The finding provides validation for prior studies of[1];[31];[18]. If one assumes that sex is a significant factor for healthy living, then its abuse can readily come into play as an unhealthy determinant.

10. Conclusions

- Family relationships and our sexuality is one of the most fundamental aspects of who we are as human beings; however it is almost underestimated particularly when exploring the development of females. It is in nature, multidimensional and directly related both to an individual's physical as well as psychosocial well-being. With regards to developing worlds and cultures, issues related to sexuality, particularly female sexuality, are often controversial. In our pluralistic society, attitudes about female sexuality differ not only according to ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religion, and geographic region, but also can vary widely within individual families and communities. The study has shown that, family closeness, social physique anxiety and sexual coercion are essential factors that could determine degrees of academic self-efficacy among undergraduates. Emphasizing on positive and effective family relationships becomes imperative in enhancing the academic self-efficacy of female undergraduates.

11. Recommendations

- Based on the result of the findings, the followings were therefore recommended:Ø That family bonding associative activities should be encouraged. Ø That family vacations, picnics, reunion parties and field trips with female undergraduates should be encouraged.Ø Since, sexual coercion and social physique anxiety reported negative relationships with academic self efficacy finding measures to reduce their occurrence could increase academic self efficacy of female undergraduates. Ø That training programmes, seminars and workshops geared towards advancing the adverse effect of these factors should be engaged.Ø Female undergraduates should be trained early in their academic career to believe in their self and their capabilities.Ø In addition academic self-efficacy training programmes should be included in orientation programmes and curriculum of the students.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML