-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Applied Psychology

p-ISSN: 2168-5010 e-ISSN: 2168-5029

2012; 2(5): 126-136

doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20120205.08

Disaster Perception, Self-efficacy and Social Support: Impacts of Drought on Farmers in South Brazil

Eveline Favero , Jorge Castellá Sarriera

Department of Psychology, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil

Correspondence to: Eveline Favero , Department of Psychology, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper aims to identify which family resources are affected by droughts. It also aims to assess which variables related to disaster perception, self-efficacy and social support better characterize groups of family farmers classified by the magnitude of the disaster’s impact. 198 farmers aged 18 to 77 years (M = 44.38, SD = 10.04) have participated, of which 104 (52.5%) are males and 88 (44.4%) are females, all residing in rural areas in the Northwest part of the State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. As instruments, a survey was applied in order to characterize the sample in terms of the disaster and its impacts on different family dimensions as well as items related to disaster perception, self-efficacy and social support. Descriptive statistics and discriminant function analyses were employed; the latter had as dependent variable the magnitude of the perceived drought impact on the family and, as independent variables, the items related to disaster perception, self-efficacy and social support. The descriptive results indicate that drought causes economic losses and changes in family routine and nutrition, generating feelings of uncertainty about the future, discouragement, sadness, and sleep difficulties. The results of the solution stepwise on discriminant analysis (Willks’ Lambda=0.78, λ²=47.844, gl=4, p≤0,001) indicate that the variables uncertainty about the future and sleep difficulties are significant to differentiate the groups of high and medium impact compared to the group of low impact of drought in the family. In a second moment, a new discriminant function analysis was employed (Willks’ Lambda = 0.76, λ² = 52.00, gl = 10, p ≤ 0.001) and showed that farmers in the groups that perceive high and medium drought impacts differ from those in the group that perceives low drought impact with regards to the variables impact of drought on well-being, perception of drought as a bad event, belief in personal responsibility for the event’s consequences and assessment of life in the midst of a disaster The high and medium drought impact groups differ in the variables related to social support, especially with regards to support perceived from family, friends, neighbors and community in relation to government, religious groups and technical support. The variable self-efficacy did not differentiate groups of farmers, suggesting it is independent of the difficulties of the environment, being much more influenced by how we evaluate and position ourselves to face difficulties.

Keywords: Disaster Perception, Self-Efficacy, Social Support

Cite this paper: Eveline Favero , Jorge Castellá Sarriera , "Disaster Perception, Self-efficacy and Social Support: Impacts of Drought on Farmers in South Brazil", International Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 2 No. 5, 2012, pp. 126-136. doi: 10.5923/j.ijap.20120205.08.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The World Health Organization and the Pan-American Health Organization[1] acknowledge the psychosocial impacts of disasters, which would affect the emotional, psychological, behavioral, physiological and spiritual dimensions of individuals. Such impacts would depend on the nature of the event, the surroundings and circumstances of life, the personality characteristics and on individual and social vulnerability[2],[1].Disasters would affect different human groups in different ways. Some of them would be considered high-risk groups, such as children – because of their dependency and because they might not fully understand what is happening - women –because they are usually subjected to more adverse social conditions and assume greater family responsibility in crisis situations - elderly - because of limitations that can lead to dependency and difficulty to adapt to extreme situations - and people with physical and mental illness - because of their psychological and social vulnerability[1]. With respect to drought, farmers could be considered a risk group when analyzing the real dependence of their activities to climatic conditions, since the well-being of rural households appears to be strongly related to success in agricultural production[3].On the other hand, disasters are events that cause economic, social and human losses, on top of natural resource losses, which are a fundamental factor in the stress process and its relation to mental health[4]. For Lazarus and Folkman[5], stress is the primary result of personal evaluation. However, cognitive assessment is a component of the stress process, and it’s also embedded in the social context[4],[6].Stress occurs where resources are threatened, lost, unstable, or where individuals or groups cannot find a way of promoting and protecting their resources through individual or collective efforts[4],[6]. The term resource has been defined as objects, personal characteristics, conditions or energies that have value in them or that are valued because they act as conductors in the acquisition or protection of other important resources[4].In addition to the environmental conditions, to the cognitive assessment of the situation and to how the resource loss happens, the perception of personal and collective efficacy may also be considered as an important component in managing stressful situations. Bandura[7] stated that the perception that individuals have about their efficacy, collective or individual, plays a key role in human functioning, affecting behavior and having effects on its determinants, such as objectives and aspirations, outcome expectations, perceived impediments and opportunities in the social environment. On this subject, the author states: "People’s shared beliefs in their collective efficacy influence the types of future they seek to achieve through collective action, how well they use their resources, how much effort they put into their group activities, their staying power when collective efforts fail to produce quick results or meet forcible opposition, and their vulnerability to the discouragement that can beset people taking on tough social problems "[8, p. 116].Similarly, the perception of available social support is one of the components of stress management and of strengthening personal and community resilience in the face of disaster. On this aspect, Garcia-Renedo, Gil Beltran and Valero Valero[9] consider social support as a moderating variable in disasters, so as to make the consequences of the event more or less devastating.The availability of social support systems is essential to ensure basic resources such as housing, food, water, medical care[6] and, in case of disasters, to limit the effects of the event on resource loss. The availability of social support would help in the process of resistance to stress and in the resource perception feedback, which is crucial for maintaining the mental health of individuals who are experiencing difficulties[10].The capacity to make resources available in post-disaster situations is also vital to community resilience, that is, the skill or process that leads to successful adaptation after trauma or severe stress[11],[12]. However, community resilience depends not only on the amount of economic resources, but also on their diversity[13], including its availability and access for all.Adger[13] highlighted that the dependence on a limited variety of natural resources can increase income variance and hamper social resilience. In this sense, extreme events like droughts, floods and pests, increase risk for those individuals who are dependent on very specific resources and decrease resilience to disaster, that is, their ability to cope with external stress or conflicts as a result of environmental, political or social change[13],[14].It is also worth considering that perceived or received social support during disaster has two critical dimensions, according to Kaniasty and Norris[15]. The first is the "origin" or "source", which reflects the general patterns of the use of aid. The first source is the family, followed by other primary support groups such as friends, neighbors, colleagues, and, eventually, formal agencies and others outside the immediate circle. Solomon, Bravo, Rubio-Stipec and Fang[16] found that perception of family support is an important moderator of disasters due to its effects on stress.The second dimension is "type", which differentiates emotional, informational and tangible (real) support. These elements are important for the development of individual and community competence in order to promote collective efficacy through the establishment of trust and organized actions[15]. According to Roncoli et al.[14], none of these types of support would be sufficient when deployed alone in disaster situations such as drought.Considering these theoretical aspects, the challenge is to understand how disasters affect the availability of family resources and what kind of resources, be they economic, social, cognitive or emotional, are fundamental to strengthen resilience and to minimize the impacts of disasters. Therefore, this paper aims to identify which family resources are affected by droughts in rural families and, within a set of variables related to disaster perception, self-efficacy and social support, to assess which ones better characterize groups of family farmers divided by the magnitude of the disaster’s impact. This paper’s findings and discussion first characterizes the sample in terms of the disaster consequences and the second analyzes the variables perception of drought, self-efficacy and social support with respect to appraisal the event’s impact on rural households.The hypothesis for this study is that there is a profile discriminant between farmers with different levels of impact of drought related to the variables perception of disaster, social support and self-efficacy. It is expected that the higher is the assessment of farmers in relation to the impacts of drought the lower will be the average in the variables related to perceived social support and self-efficacy. Social support would limit the effects of drought in the loss of resources [6], whereas the perception of self-efficacy would help in the management of successful stress situation [7], moderating its adverse impacts.It is also expected that the higher is the assessment of the impacts of drought in the family, the higher will be the average in items related to the negative perception of the disaster. It is understood that to the extent that the disaster is better controlled, the negative perception would less significant [24]. Furthermore, it is believed that the variable income can be influencing the impact of drought on farm family.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics[17] 5.510 people (2.893 are men and 2.617 are women) reside in the rural area of the city of Frederico Westphalen-RS, place selected for research due to the occurrence of droughts. The municipality is located in the northwestern region of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. The main activities undertaken by these rural households are grain crops (soybean, maize, black beans, wheat, oats, peanuts and popcorn maize, among others), fruits, milk production, pig farming, livestock, and familyagro-industries[17]. This study surveyed 198 farmers aged 18-77 years (M = 44.38, SD = 10.04), 104 (52.5%) are male and 88 (44.4%) female. The following sample inclusion criteria were applied: to be 18 years old or older, to be a resident of the selected city for the last five years and to have agriculture as the main source of family income. The sample distribution by income occurred as follows: 73 participants (39.2%) had a family income below of one minimum salary, 63 participants (33.9%) had a family income of over one and up to two minimum salary and 50 participants (26.9%) had a family income of more than two and up to four minimum salaries. The average family income of participants was less than two minimum salary (M = 1.88; SD = 0.059), with a minimum salary equivalent to approximately $ 310.00. It appears that the population in analysis shows quite low family income.

2.2. Instruments

- 1) Survey that characterizes the sample according to the impact appraisal of disasters on family resources. Questions related to the consequences of drought on the family life of farmers, with categorical responses, are part of this instrument. Some examples are: “has the family needed to change plans or projects” and “has the family incurred debt because of drought”. The questions were developed based on a previous study on the main impacts of drought in this population and that was part of the thesis work of the first author [31].2) Survey items with responses ranging from 0 = none and 4= totally, divided into the following categories: a) Perception of the disaster, seeking to evaluate the ideas or judgments about the drought and attributions of responsibility for its consequences. The following items are part of the questionnaire: How much do you consider that drought affects health and well-being, how bad do you consider drought to be, how responsible do you consider yourself for the impacts of drought, how better do you believe your life would be without droughts. b) Self-efficacy, referring to the assessment of personal belief to be able to cope with disaster. The following items are part of the questionnaire: How prepared do you consider yourself for dealing with drought, how used to drought do you consider yourself to be, how capable do you consider yourself in dealing with the difficulties caused by drought. c) Social support referring to the perception of its availability in different groups of social networking of farmers. The following items are part of the questionnaire: How much support do you believe you receive when a drought occurs: from family, from friends, from neighbors, from the religious group you participate, from the government, from agricultural technicians, from the community, from credit institutions.3) Ad hoc Index of Drought Impact on Family (IDIF). In a five-point Lickert scale in which 0 = none and 4 = totally, participants choose how they evaluate affected by droughts they consider themselves and their families to be in the following categories: financial, psychological, leisure, clothing, sleepness, studies (theirs or their children’s), family relationship and family routine. The categories were grouped from a qualitative study, developed by the first author with the same population, which identified the key family dimensions affected by drought [31].Through exploratory factor analysis with principal axis extraction method and oblique rotation, the scale was found to be unifactorial (KMO = 0.834; Bartlett's Test ≤0.001), with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83 and 46.2% of explained variance.

2.3. Procedures

- The research was carried out after the approval by the Ethics Committee of the Psychology Institute at UFRGS, under the protocol number 2010/003. The participants signed a term of free and clear consent, according to the ethical criteria for research with human beings in Resolution 196/96 of the National Health Council[18]. The survey was filled out individually.After a pilot study with 30 farmers was undertaken to verify the adequacy of the instruments, the survey and consent terms were handed to students of municipal and state schools identified as children of farmers in the city of Frederico Westphalen/RS. The procedure was authorized by the State Department of Education and by the schools’ administration. Students took the survey to their parents or guardians to fill out and returned them to the school along with the consent term. The surveys were then collected by the researcher.To cover the rural area of municipality as a whole and to consider potential regional differences, a zoning was carried out during the application of the survey, dividing the rural area as located in far, near or intermediate distances from the town hall, seeking a roughly equal number of participants in each zone. 19.7% of the sample belongs to the zone near the town hall (n = 39), 31.8% belongs to the zone located within intermediate distance (n = 63) and 43.9% belongs to the farthest zone (n = 87). The fact that there are fewer participants in the area near to main office can be explained due to a phenomenon named “rurban”[19],[20], in which many people use rural areas as a residence but actually work in nonfarm activities. Thus, many didn’t meet the research inclusion criterion to work in agriculture. On the other hand, more distant areas remain almost essentially agricultural and therefore a more representative sample was obtained.

2.4. Data Analysis

- Descriptive statistics were employed to characterize the sample according to the impact of drought by using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (v.17). Subsequently, discriminant function analyses were conducted in two phases. The dependent variable was the farmer groups by level of perception of the impacts of drought in the family. At first the independent variables were the items of the questionnaire sample characterization on the disaster. Secondly, the independent variables were the items of the questionnaire on perception of the disaster, self-efficacy and social support. Finally, linear regression analysis were performed having as the dependent variable the sum of the items IDIF. The independent variables were the items of the questionnaire about the disaster perception, social support and self-efficacy. The income variable was also included in this analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sample Characterization According to the Impact of Disaster

- In order to characterize farmers according to the impacts of drought on family resources, descriptive statistics analyses were conducted. The results (Table 1) show that the majority of the sample (91.9%) has experienced drought in the last five years (2005-2010), has changed family plans and projects (85.9%) and more than half of participants had to take on debt because of drought (63.1%).Within the set of possible losses in family resources, in order of importance, most participants considered that drought has caused losses in agriculture, food shortages, losses in milk production and lack of water for animal and human use. These data draw attention to food security issues in this population due to the loss of survival resources, as water and food.From the standpoint of the psychological impact, in the participants’ opinion drought creates uncertainty about the future (72.7%), disencouragement and sadness (72.2%) and sleeping difficulties (50.5%). The data that characterizes the impact of drought on rural families also reveals the need to change life plans (85.9%) and debt incurrence (63.1%), which has an impact on family organization.There is evidence that the consequences of drought have an effect on the participants’ plans for the future, which might be related to psychological reactions such as discouragement and sadness. The resource losses undoubtedly influence psychological well-being, as found in other studies, through symptoms such as anxiety and irritability[6].On the other hand, the need to change plans or projects is an interesting finding because it shows that disasters impose changes in life trajectories, which is not necessarily a negative happening. Having a new direction in life could increase the possibility of obtaining resources and could make individuals more resilient to drought, what, in terms of the ability to adapt to the requirements of each context, might be a health indicator for this population.Another finding concerns debt incurrence, which is an important element in understanding the social vulnerability of rural households in this context. For Roncoli et al.[14], borrowing money is a survival strategy only used by the poorest families and when every other resource to cope with droughts is exhausted. Accordingly, when loss occurs (in this case agricultural production), it usually triggers the loss of other important resources[6], and families that have fewer resources would be the most vulnerable due to the difficulty to adopt strategies in order to control the situation[21].From a psychological standpoint, Hobfoll[21] stated that depression is a symptom likely to occur when the investment of resources fails to solve a conflict. In the case of agriculture, crop investment is usually the main method to ensure family survival. When the actual result does not meet expectations, not only economic and social consequences are triggered, but psychological reactions become prominent through sleep deprivation, sadness and uncertainty about the future, for example, what was also reported by Bosch[22] in another context. In this sense, the diversification of earnings in rural households could be important to ensure that not all expectations are frustrated in the event of drought, so that rural populations become more resilient to climatic factors, as suggested by Adger[13] and Roncoli et al.[14].

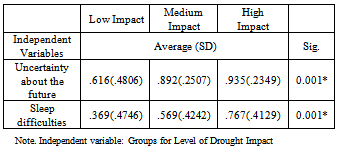

3.2. Discriminant Profile of the Sample in Relation to Disaster

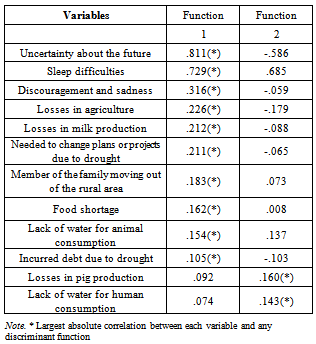

- In order to classify farmers in groups according to drought impacts on the family by identifying profiles through discriminant criteria, a three level measure was created, starting from the tertiles of the sum of the ad hoc Index of Drought Impact on Family (IDIF) items. The groups were characterized by: Low Impact (n = 67, 33.8% of the sample), Medium Impact (n = 61, 30.8%) and High Impact (n = 70, 35.4%). The scale ranged from 0.5 to 3.5, cut at 1.5 (separating the groups that experienced Low and Medium Drought Impacts) and 2.5 (separating the groups that experienced Medium and High Drought Impacts).The discriminant analysis was performed at this point; estimated discriminant functions are similar to linear regression lines (a linear combination of variables) and seek to explain the variation or differences in categorical dependent variables (in this study the DV is the magnitude of drought impacts, divided in groups) according to Hair et al.[23]. Function 01 explains (represents) the largest amount of variation (difference) while Function 02, which is orthogonal and independent with respect to the first, explains the high percentage of residual variation, after the variance of the first function is removed.With regard to items relating to losses from drought (Table 01) and their relevance to discriminate groups of farmers, analysis of the centroids of the groups showed that the group with high (.514) and the group of medium impact (.156) differentiate the group of low impact (-.679) in Function 1. Moreover, the group of medium impact (-.174) differs from the high-impact group (.106) in Function 2.The coefficients in the canonical discriminant functions were 0.455 (p≤ 0.001 and 94.8% of explained variance) in Function 1, and 0.119 (p≤ 0.097 and 5.20% of explained variance) in Function 2.Table 2 presents the standardized structural matrix of coefficients, being the variables sorted by their gross size correlation (z discriminant scores) in each function. It appears that the psychological variables have a higher weight to differentiate groups of farmers compared with other consequences of drought on family resources. Desse modo, o grupo de alto impacto e o grupo de médio impacto diferenciam-se do grupo de baixo impacto, especialmente, nas variáveis uncertainty about the future (z=.811), sleep difficulties (z=.729) and discouragement and sadness (z=.316). The variables that follow differentiating these groups, although with smaller weights are losses in agriculture (z = .226), losses in milk production (z = .212) and need to change plans or projects due to drought (z = .211).The group of medium impact differs from the high-impact group on the variables losses in pig production (z = .160) and lack of water for human consumption (z = .143). In relation to this information, it appears that what differentiates farmers of medium and high impact of drought refers to a greater or lesser availability of water, once the breeding of pigs is an activity highly dependent on water resources. Thus, the availability of water for both human and animal consumption is a factor that determines the degree of impact of drought in the family. Although the weight of these variables is not as expressive to differentiate groups of farmers, it is understood that water availability may be a factor that marks a difference between groups of high and medium impact of drought in the family.

|

|

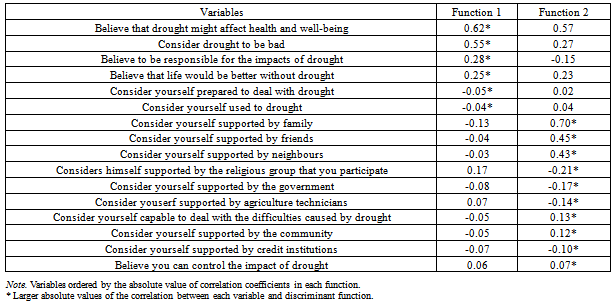

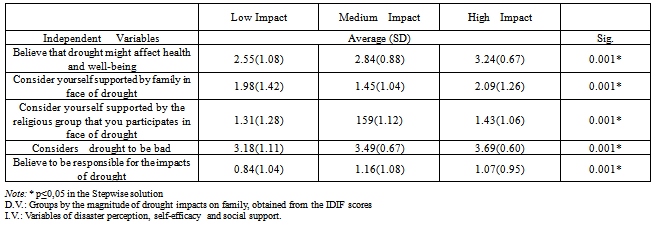

3.3. Differences between Groups of Farmers on the Perception of the Disaster, Social Support and Self-efficacy

- Using the same measure created from IDIF to separate groups of farmers for drought impact on the family, we performed a new discriminant analysis. This second analysis aimed to identify variables of the questionnaire, among which assess perception of the disaster, social support and self-efficacy, better differentiate groups of farmers by perceived impact of drought.The analysis of the groups’ centroids shows that Function 1 differentiates the groups of farmers that experienced high (0.350) and medium (0.281) drought impact from the group with low impact (-0.622). In turn, Function 2 differentiates the group with high drought impact (0.327) from the group with medium drought impact (-0.404). The coefficients in the canonical discriminant functions were 0.41 (p≤ 0.001 and 69.2% of explained variance) in Function 1, and 0.29 (p≤ 0.002 and 30.8% of explained variance) in Function 2. The discriminant analysis sought to identify which variables best characterize the three groups formed by perceived drought impact magnitude. Table 3 presents the structural matrix, where all the variables analyzed are ranked in absolute values (standardized weights) of their correlation (discriminant z-scores) with the respective discriminant function (1 and 2).

|

|

3.4. Discriminant Variables Related to Disaster Perception

- Analyzing the correlation coefficients of each variable in Function 1, the perception that drought affects health and well-being is the first that differentiates groups in the sample (z = 0.62). The groups that are affected the most by drought, that is, those with high and medium impacts on aspects such as financial, psychological, leisure, clothing, sleepness, studies, relationships and family routines, also believe that drought has impacts on family health and well-being.The second variable that differentiates the groups with high and medium drought impact from the group with low impact is perception of drought as a bad event (z = 0.55). Disaster perception is an important factor when it comes to assessing attitude towards risk. According to Pennings and Grossman[24], disasters such as drought have predictable outcomes, so people who experience this event know its damage and loss potential. For that reason, it should also be more easily managed and therefore, to the extent that the disaster is better controlled, the negative perception would less significant. On the other hand, drought is an uncertain event in terms of when it occurs[25]. Given this uncertainty, it’s expected that fewer people adopt preventive behaviors that facilitate adaptation to disaster[24],[26], such behaviors would reduce the negative perception because of a better control of the situation.Disasters are events that challenge the adaptability of individuals, and therefore carry the risk of adverse consequences on mental health[27],[28]. It can be inferred from this study that families that are better adapted to drought have developed further mechanisms to minimize its impact, therefore perceiving drought as a less threatening event as well as reducing its negative consequences on health and well-being.The variable belief in individual responsibility for the impacts of drought also differentiates the groups with high and medium drought impact from the group with low impact (z = 0.28). In the case of disasters, the feeling of personal accountability is very common, especially in those events with little public and media attention[25] or in which risk of life is indirect[26].Personal accountability might be related to perceived self-efficacy, which plays a key role in human functioning, affecting behavior and having an impact on its determinants such as objectives and aspirations, outcome expectations and perception of obstacles and opportunities in the social environment[7]. Self-efficacy is also the basis of human agency, so that people who believe they cannot produce the desired outcomes through their actions also have little incentive to act and persevere in difficult times[29]. In this sense, to feel responsible for a situation is not enough to produce a change in behavior. The individual also needs to believe in his personal self-efficacy and in the results of the actions undertaken, whether individual or collective.In this context, belief in individual responsibility might also be related to learned helplessness, which is a state of pessimism that results from trying to explain a negative event from stable, internal and global factors[30]. This would lead to hopelessness, depression, decreased stress responsivity and, consequently, to less positive results in stress management. In the case of drought, the feeling of helplessness is often observed[31], which may be related to its own unpredictability[25]. In this sense, the way that farmers interpret the causes of the drought can result in feelings of helplessness, which affects attitudes and behaviors. Moreover, only the consequences of disaster can be controlled, not disaster itself, so that a change in the focus of how to perceive the event might also result in better outcomes in responsivity.Another evidence derived from this study is that the groups that experienced high and medium drought impacts also differ from the group with low drought impact in the variable belief that life would be better without drought (z = 0.25). This can be explained by the fact that a greater control over the consequences of drought would produce a smaller interference of disaster in personal and family life, in the sense that the group with the lowest drought impact does not notices big changes in life in face of a drought, as opposed to the groups that experienced high and medium impacts.

3.5. Discriminant Variables Related to Social Support

- In regards to the identification of variables that characterize the groups in Function 2, these are related to perceived social support. The first, to feel supported by family in face of drought, differentiates the groups with high and medium drought impact (z = 0.70). The group most affected by drought believes to receive more support from family, which is an interesting finding. The hypothesis was that the group with the highest perceived impact of the drought would present lower perceived social support, since the latter is a moderator of the negative consequences of the disaster.The same is true for the variables support from friends (z = 0.45), support from neighbors (z = 0.43) and support from the community (z = 0.12), as opposed to other variables such as support from religious groups (z = -0.21), support from the government (z = -0.17), technicians support (z = -0.14) and support from credit institutions (z = -0.10). It’s possible to observe in the overall set of variables that the group that experienced high drought impacts perceives more support from primary groups (family, friends, neighbors, community), while the group with medium drought impacts perceives more support from outside groups (religious groups, government, technicians).The source of social support in disasters was discussed in Kaniasty and Norris[15] and it’s reflected in the general pattern of use. Usually, first, groups such as family, friends, neighbors and colleagues are accessed, and then formal institutions and other people outside the immediate circle, what also depends on the set of relations that form people’s social capital.Analyzing the results, the group of farmers that perceives to be the most affected by drought may be using more primary groups’ support, since the impacts of disaster are related to family survival, which leads to the search of more immediate solutions. In this sense, support from outside groups, although present, may not be the first to be accessed or may not be permanent or adequate in order to meet the family’s demand, or even take too long to be available. On the other hand, support from primary groups would be immediate and constant, part of the farmers’ daily routine.Another possibility is that, regarding the group with medium drought impact, farmers might have developed coping mechanisms so that disasters do not affect family survival dimensions. Therefore, aid from external groups would make a difference in times of drought, although not as much as an emergency response. They could also be relying on prevention mechanisms such as crop insurance and other sources of aid that would help in the minimization of losses. Regarding the group with small drought impact, the lack of association with variables of social support may show the development of autonomy in families coping with droughts.In this sense, recognizing the importance of support from primary groups in the minimization of losses and in the increase of disaster resilience[15],[16], especially in farmers highly affected by drought, psychosocial interventions could focus on promoting and strengthening family, friends and neighborhood ties. Perception of support is also an important stress moderator[16] and it’s maintained with actual received support. Stress situations such as disasters evoke solidarity actions and the supply of external support tends to increase, so that resource availability perception also increases at first, but later decreases with the removal of such aid. In this case, in order for the perceived support to be maintained, long term actions that meet the specific needs of each group of farmers, whether financial or psychosocial, are required, rather than solidarity or emergency actions in times of drought.

3.6. Discriminant Variables Related to Self-efficacy

- Finally, the variables “do you consider yourself prepared, used and capable to deal with droughts” as well as the variable “do you believe you can control the impacts of drought,” do not differentiate groups of farmers divided by the magnitude of drought impacts. It was expected that these variables would characterize differently the three groups, since they represent different levels of perceived self-efficacy to deal with the event. A possible interpretation of this finding is that self-efficacy is independent of the difficulties of the environment, being much more influenced by how we evaluate and position ourselves to face difficulties. Self-efficacy is the exercise of control, according to Bandura[33], and that people with low self-efficacy perceive fewer opportunities to exercise control or, when they try, are easily convinced of the futility of this effort in the face of difficulty[29].Moreover, the perception of self-efficacy varies in amplitude when the objects of change are social or personal problems, according to Fernández-Ballesteros et al.[29]. People would have a stronger sense of efficacy to control aspects of life in their immediate environment rather than in issues of the social sphere. In this sense, the fact that drought is a collective problem, with losses not only in the personal but also in the social sphere, could lead farmers to be less confident about their ability to control and manage the event in the family level.One hypothesis is that this belief does not vary with the drought impact magnitude due to the type of the object, that is, a collective problem in that population. In this sense, the perception of efficacy could increase as long as people work collectively, reaching more effective outcomes than when acting alone[8]. Collective action allows resource, knowledge and skill sharing, promotes mutual support, which is required to sustain collective efforts and to address difficulties that arise in the process of social change[29], therefore becoming an important element in coping with disaster situations.

3.7. Inclusion of the Income Variable in the Analysis of the Impact of Drought in the family

- Considering the need to assess whether the income variable exerts some influence on the level of impact of drought in the family, and for comparison with the results of discriminant analysis, a linear regression analysis was employed verifying the extent each variable contributes as a predictor of drought impacts on the family. For this analysis, we used as dependent variable the sum of IDIF scores, while the independent variables were all items listed in Table 3, adding the variable income.A linear regression analysis by the stepwise method did not bring contributions to the results of this study, indicating that the selected variables are not adequate to assess the aspects that would influence the impact of drought in the family. Although it was expected that income would influence the impact of the disaster, it is necessary to consider some aspects of this study. Firstly the IDIF evaluates the perception of the impact of drought in the family, i.e., a subjective evaluation that does not necessarily correspond to the actual impact of the disaster. On the other hand it is possible that the group who perceives high impact of the drought has also more problems related to the availability of water for human and animal consumption, which has negative repercussions on agricultural gains and activities such as swine and milk production. Thus, this group is not necessarily the one with the lowest income, but possibly the one with the greatest fluctuation in income due to climate variations. In addition, farmers producing milk and pork are also those who are investing more in improvements on the property due to health requirements for the performance of these activities, most often using credit institutions and contracting debts. Finally, there is in the investigated population a large number of farm families that have one or more retired members which ensures a more stable income, even in times of drought. Thus, different variables may be influencing the perception of the impact of the disaster, so that the isolated assessment of income is not sufficient to predict the impact of drought in this population.

4. Conclusions

- The field of rural psychology and the psychology of disaster area still require advances in Brazil. In this sense, the study aimed to contribute in discussions on these two areas of knowledge related to the problem of drought, which lacks attention to its psychosocial impacts especially in rural populations. It is understood that the drought is a disaster by triggering loss of resources and significant changes in the environment, being also characterized by uncertainty about the future and prolonged exposure to stress.In this particular study (which is part of a research that uses different scales), we chose to use a questionnaire with items formulated for the specific context of the study, which were drawn from an exploratory research. Although, this kind of choice can bring some statistical disadvantages in relation to other instruments that have already been tested in other populations, we chose to assess those variables that make sense within the context under study and thus are able to explore the specifics of disaster in this population.The study of the impacts of drought on rural families found that drought causes the loss of essential survival resources, such as agricultural losses, food shortage, losses in milk production and lack of water for animal and human consumption. Furthermore, some psychological impacts were identified, such as uncertainty about the future, discouragement, sadness and sleep difficulties in a sample of farmers in South Brazil.The results support the findings of other studies such as Bosch[22] and Roncoli et al.[14], and show the specificities of the analyzed context, which is characterized by family farmers who have agriculture, pig farming or milk production as their main source of income. Moreover, uncertainty about the future, sleep difficulties and feelings of discouragement and sadness were found to be very important in the sample, and could be further analyzed in future research about the relationship of disasters with the incidence of depression in this population. The first two variables are also significant to differentiate groups of farmers for drought impact, and the groups of medium and high impact of the disaster showed higher average compared to the group of low impact.The research also found that farmers can be characterized differently in groups of variables related to the perception of drought as a negative event and to the perception of individual responsibility for the impacts of drought. In this sense, the groups that experienced high and medium drought impacts perceive disasters more negatively than the group with low drought impacts and also believe to be more accountable for impacts on family life, which might be related to explaining a negative event through stable, internal and global factors[30]. It is important to further analyze whether a relationship exists between responsibility allocation, sense of personal worth and belief in the capacity to control the impacts of disaster.Regarding social support, the findings showed a greater association between the perception of support from primary groups and farmers who are most affected by the impacts of drought. This type of support is by far the most accessible during disaster situations and therefore needs to be promoted[34]. On the other hand, farmers that experienced medium drought impacts perceive to receive more social support from outside groups than the group with high drought impacts. The bigger the depletion of survival resources, the higher the need for quick and effective aid and for immediate relief through external assistance in order to avoid what Kaniasty, Murrel and Norris[18] called the “erosion of perceived social support,” that is, the chronic consequences of disaster on psychosocial well-being, which reduce the perceived availability of this important resource.In this sense, there is a need to increase the perception of social support by the farmers most affected by drought in addition to the support received from primary groups, in order to promote health and well-being in this population, while strengthening relationships with family, friends, neighbors and community. Those relationships might be responsible for the maintenance of psychological health in this group in daily life, despite adversities. Perceived support is retrofitted through received support[32], so that the supply of social support may be also mediating its perception of availability, moreover, this should not be only related with quantity, but with the adequacy and permanence of the supply of this resource.Sample size might be considered one of the limitations of this study, what is a reflection of rural exodus, the population’s low educational level and the geographical difficulties to access rural residents. It is also recognized that the context of family farms is too specific to be generalized to other rural realities, although these findings may contribute to the development of comparative studies. On the other hand, were not found high levels of statistical significance in some analyses, so that it is suggested some differences between groups be considered with reservation. In this sense, a refinement of the instruments could also contribute to better results in the investigated variables. Finally, psychology can contribute with knowledge in community interventions by promoting organized actions that strengthen social support relations and generate the opportunity for problem and solution sharing, providing an overview of the existing opportunities in this social environment. In addition, psychosocial care plays an important role in promoting individual and community resilience, manifested through higher levels of well-being of those who go through prolonged stress situations such as drought, and may contribute to the development of belief in individual and collective efficacy to deal with everyday challenges.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We thank the National Research Council (CNPq, Brazil) for financial support in developing this work.

References

| [1] | Organización Panamericana de La Salud (OPAS), & Organización Mundial de La Salud (OMS). (2010). Apoyo psicosocial em emergencias y desastres: Guia para equipos de respuesta. Washington, D.C.: OPAS. |

| [2] | Boyd, B., Quevillon, R. P., & Engdahl, R. M. (2010). Working with rural and diverse communities after disasters. In P. Dass-Brailsford (Ed.), Crisis and disaster counseling: Lessons learned from hurricane Katrina and other disasters (pp. 149-163). Los Angeles: Sage. |

| [3] | Logan, C., & Ranzijn, R. (2008). The bush is drying: A qualitative study of South Australian farm women living in the midst of prolonged drought. Journal of Rural Community Psychology, 12(2). Disponível em:http://www.marshall.edu/jrcp/VE12%20N2/jrcp%2012%202%20Logan%20and%20Ranzijn.pdf |

| [4] | Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 50(3), 337-421. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00062 |

| [5] | Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer. |

| [6] | Ünal-Karagüven, M. H. (2009). Psychological impact of an economic crisis: A Conservation of Resources Approach. International Journal of Stress Management, 16(3), 177-194. doi 10.1037/a0016840 |

| [7] | Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science 1(2), 164-180. |

| [8] | Bandura, A. (2008). O exercício da agência humana pela eficácia coletiva. In A. Bandura, R. Gurgelazzi, & S. Polydoro (Eds.), Teoria social cognitiva: Conceitos básicos (pp. 115-122). Porto Alegre: ArtMed. |

| [9] | Garcia-Renedo, M., Gil Beltrán, J. M., & Valero Valero, M. (2007). Psicología y desastres: Aspectos psicosociales. Castelló de la Plana: Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I. |

| [10] | Norris, F. H., & Kaniasty, K. (1996). Received and perceived social support in times of stress: A test of the social support deterioration deterrence model. Journal of Personality ans Social Psychology, 71(3), 498-511. |

| [11] | Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., & Pfeferbaum, R. (2007). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 127-150. doi: 10,1007/s10464-007-9156-6 |

| [12] | Norris, F. H., Tracy, M., & Galea, S. (2009). Looking for resilience: Understanding the longitudinal trajectories of responses to stress. Social Science & Medicine, 68, 2190–2198. |

| [13] | Adger, W. (2000). Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Progress in Human Geography, 24, 347-364. |

| [14] | Roncoli, C., Ingram, K., & Kirshen, P. (2001). The costs and risks of coping with drought: Livelihood impacts and farmers responses in Burkina Faso. Climate Research, 19, 119-132. |

| [15] | Kaniasty, K., & Norris, F. (2000). Help-seeking comfort and receiving social support: The role of ethinicity and context of need. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 545-582. |

| [16] | Solomon, S. D., Bravo, M., Rubio-Stipec, M., & Canino, G. (1993). Effect of family role on response to disaster. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6(2), 255-269. doi:10.1002/jts.2490060208 |

| [17] | Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). (2010). IBGE Cidades. Disponível emhttp://www.ibge.gov.br/cidadesat/topwindow.htm?1 |

| [18] | Conselho Nacional de Saúde (CNS). (1996). Resolução 196/96 sobre pesquisa envolvendo seres humanos. Bioética, 4(2), 15-25. |

| [19] | Schneider, S. (1995). As transformações recentes da agricultura familiar no RS: O caso da agricultura em tempo parcial. Ensaios FEEE, 16(1), 105-129. |

| [20] | Silva, J. G. (1997). O novo rural brasileiro. Nova Economia, 7(1), 43-81. |

| [21] | Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513-524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513 |

| [22] | Bosch, K. R. (2004). Cooperative extension responding to family needs in time of drought and water shortage. Journal of Extension, 42(4), 1-10. |

| [23] | Hair, J. F.; Anderson, R. E.; Tathan, R. L., & Black, W. C. (2005). Análise multivariada de dados. Porto Alegre: Bookman. |

| [24] | Pennings, J. M. E., & Grossman, D. B. (2008). Responding to crises and disasters: The role of risk attitudes and risk perceptions. Disasters, 32(3), 434-448. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.2008.01048.x |

| [25] | Pereira, L. S., Cordery, I., & Iacovides, I. (2002). Coping with water scarcity (Technical Documents in Hidrology no. 58). Paris: UNESCO. |

| [26] | Smith, K. (1992). Environmental hazards: Assessing risk and reducing disaster. New York: Routledge. |

| [27] | Davidson, J. R. T., & McFarlane, A. C. (2006). The extent and impact of mental health problems after disaster. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(2), 9-14. |

| [28] | Reyes, G. (2006). International disaster psychology: Purposes, principles and practices. In G. Reyes, & G. A. Jacobs (Eds.), Handbook of international disaster psychology: Fundamentals and Overview (pp. 1-13). Westport, CT: Praeger. |

| [29] | Fernández-Ballesteros, R., Díez-Nicolás, J., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., & Bandura, A. (2004). Determinantes y relaciones estructurales desde la eficacia personal a la eficacia colectiva. In M. Salanova et al., Nuevos horizontes en la investigación sobre la auto-eficacia (pp. 68-80). Castelló de la Plana: Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I. |

| [30] | Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E. P., & Teasdale, J. D. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87(1), 49-74. |

| [31] | Favero, E. (2006). A seca na vida das famílias rurais de Frederico Westphalen-RS (Dissertação de Mestrado, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Extensão Rural, UFSM, Santa Maria, Brasil). Disponível emhttp://www.dominiopublico.gov.br/pesquisa |

| [32] | Kaniasty, K., Norris, F., & Murrel, S. A. (1990). Received and perceived social support following natural disaster. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 20, 85-114. |

| [33] | Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Worth Publishers. |

| [34] | Dass-Brailsford, P. (2010). Effective disaster and crisis interventions. In P. Dass-Brailsford (Ed.), Crisis and disaster counseling: Lessons learned from hurricane Katrina and other disasters (pp. 213-228). Los Angeles: Sage. |

| [35] | Renn, O. (2008). Risk governance. Coping with uncertainty in a complex world. London: Earthscan. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML