-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2022; 12(4): 115-122

doi:10.5923/j.ijaf.20221204.02

Received: Oct. 22, 2022; Accepted: Nov. 16, 2022; Published: Dec. 14, 2022

Non-Timber Forest Products: An Evaluation of Stakeholders’ Knowledge, Utilization and Prospects for Development in Dasse Chiefdom, Moyamba District, Sierra Leone

Adegboyega Ayodeji Otesile1, Alford Aaron Fidawi2

1Department of Forestry, Njala University, Sierra Leone

2Department of Silviculture, Miro Forest Company, Sierra Leone

Correspondence to: Adegboyega Ayodeji Otesile, Department of Forestry, Njala University, Sierra Leone.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

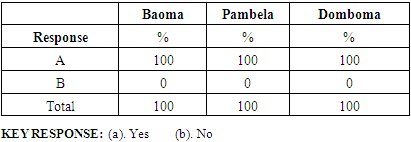

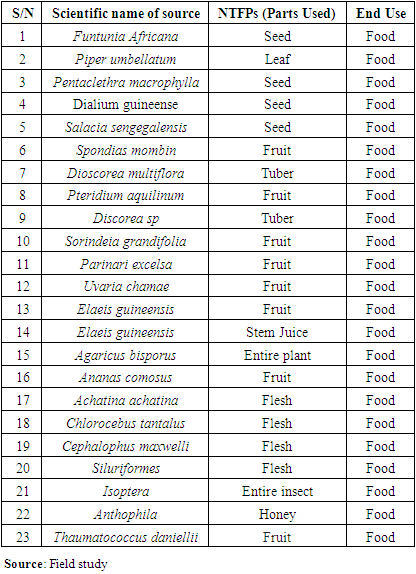

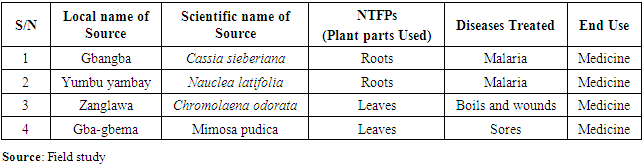

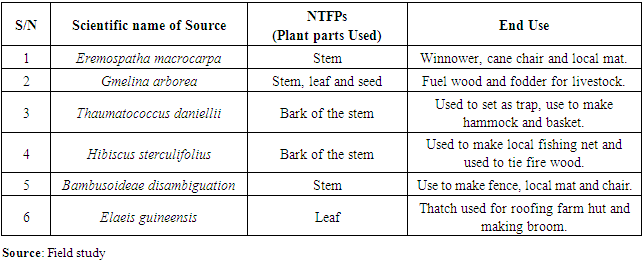

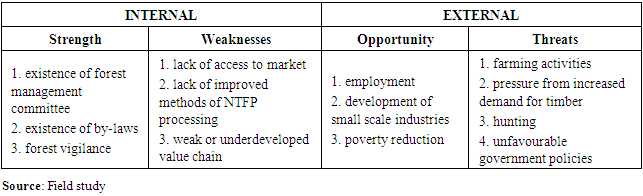

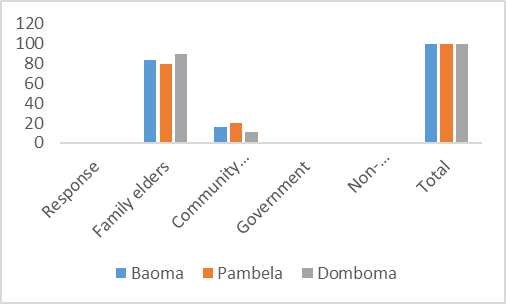

A survey on available Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) was conducted in community forests within Baoma, Pambela and Domboma communities in Dasse Chiefdom, Moyamba District, Sierra Leone. The aim was to evaluate community inhabitants’ knowledge of the uses of these NTFPs. Plant and animal parts exploited by inhabitants were identified and a strength, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis of NTFPs potentials for development in the study areas was also conducted. Data were collected using structured questionnaires, interviews and ocular observations. Sixty-five questionnaires, representing 100% of adult population of the communities was administered. Data was analyzed using descriptive analysis. Thirty-two NTFPs of plant and animal origins was identified to be used by the people in the communities studied. All respondents claimed to know the uses of NTFPs identified in their respective communities; with most of them (Baoma - 84.00%, Pambela - 80.00% and Domboma - 89.29%) acquiring such knowledge from elders while growing up in their families. Respondents accounts revealed that, identified NTFPs were used for: medicines, food (e.g. plants, wild game and honey) and other uses such as fodder, winnower, fasteners, fuel-wood, game traps, local floor mat, home roofing, fishing nets and craft, e.g. (from rope, tree branches and rattan). Findings from the SWOT analysis revealed that the strict enforcement of subsisting bylaws in the 3 communities is a major source of strength to NTFP development in the communities; while lack of access to wider market is a weakness. However, prospect of employment to the people represents opportunities from NTFP development in Baoma and Pambela, while prospects of promoting poverty alleviation and local development signifies opportunities in Domboma. Farming activities in the community forests is seen as the major threat to NTFP development in the 3 communities.

Keywords: Non-timber forest products (NTFPs), Boama, Pambela, Domboma, Community Forest, Sierra Leone

Cite this paper: Adegboyega Ayodeji Otesile, Alford Aaron Fidawi, Non-Timber Forest Products: An Evaluation of Stakeholders’ Knowledge, Utilization and Prospects for Development in Dasse Chiefdom, Moyamba District, Sierra Leone, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 12 No. 4, 2022, pp. 115-122. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20221204.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Since the early 1990s, the role of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) for sustainable forest use and poverty alleviation has received increased attention (Cifor, 2003). The original idea on the potential of NTFP exploitation as a way to sustainable forest management was primarily based on the assumption that the commercial extraction of NTFPs from natural forests could simultaneously serve the goals of biodiversity conservation and poverty alleviation, (Anderson, 1990; De Beer and McDermott, 1989; Ahenkan and Boon, 2008; Panayotou and Ashton, 1992; Plotkin and Famolare, 1992; Ros-Tonen et al., 1995; Ruíz Pérez, 1996).According to Tinde, (2006), NTFPs form an integral part of the livelihood of the 500 million people who live in or near tropical forests. Even though this number may be deemed a low estimate, and does not reflect the large number of temperate and boreal forest users, it nevertheless provides us a good indication of and the important roles forest resources play in the lives of rural people.Non- Timber Forest Products comprise medicinal plants, dyes, mushrooms, fruits, resins, tree bark, roots and tubers, leaves, flowers, seeds, honey and so on and are sources of food and livelihood security for communities living within forests and its fringes. NTFPs are also called “minor forest products” in national income accounting systems and also known as Non-wood, secondary, special or specialty forest products (Shackleton, et.al., 2011).Compared to timber, the harvesting of NTFPs seemed to be possible without major damage to the forest and its environmental services and biological diversity. In sum, NTFPs are expected to offer a model of forest use which could serve as an economically competitive and sustainable alternative to logging.Hunting is one of the oldest and most basic relationships between humans and the natural world. However, contrary to popular perception, hunting continues to be widely pursued in rural areas across the globe, particularly within forested ecosystems that provide food, fibres and medicine for subsistence use and for trade. Nonetheless, the promotion of NTFPs commercialization as a pathway to forest conservation and rural development has proven to be contentious; nevertheless, researchers have queried the value of creating NTFP exploitation hubs (Sunderland, et.al., 2004), the practicability of marketing rainforest products (Dove, 1993), and the sense in integrating NTFPs into rural development strategies (Emery, 1998). Homma, (1992) concluded that NTFPs form an unsteady economic base for rural people and hypothesized that NTFP collection pressures bring about one of two fates: overexploitation and plant population decline, or replacement by systems that offer cheaper economies of scale, principally domestication or synthetic substitution. Homma’s hypothesis is invalid when applied to subsistence use of NTFPs, though it indicates some major challenges in NTFP commercialization and the integration of NTFPs into rural development schemes.Globally, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and donors are promoting green certification as a market-based tool to support environmental sensitivity in production practices in the forest industry. Consequently, hundreds of millions of hectares of forests have been certified worldwide for timber production, and various interest groups are also certifying NTFPs. Although this is not yet the situation in Sierra Leone, some effort are currently being made to conserve areas with high biodiversity under a ‘Community Based Forest Management (CBFM)’ project pioneered by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations – Sierra Leone (FAO -SL). The 3 year programme which started around 2015, secured and conserved about 50 hectares of biodiversity rich forests in 4 pilot communities (Baoma, Pambela, Domboma and Gbaima-songa) and identified NTFPs as a key component. Aside the fact that these communities had small human populations and were selected due to their respective richness in biodiversity, the project managers also found that traditional heads and inhabitants of these communities did not tolerate commercial exploitation of wood products from forests in their communities; especially for fire-wood and charcoal production.This study therefore sought to investigate knowledge-base of residents in each of these 3 communities (Baoma, Pambela and Domboma, Mano-Dasse Chiefdom, Moyamba District) about the importance of NTFPs, how they impact social and economic lives of the people and prospects for the development of NTFPs in those communities.

2. Methodology

2.1. Description of Study Area

- The three communities studied for this research are located in the Mano-Dasse Chiefdom, Moyamba District, Sierra Leone.

2.1.1. Moyamba District

- Moyamba district is in the Southern Province of Sierra Leone and borders the Atlantic Ocean in the west, Port Loko district and Tonkolili district to the north, Bo district to the east and Bonthe district to the south. It has a population of 346,771, (Statistics Sierra Leone, 2021) and lies on 8°00N 12°30W and its capital and largest city is Moyamba. Other major towns include Njala, Rotifunk and Shenge. The district is the largest in the Southern Province by geographical area with a land area of 6,902 km2, (Wikipedia.org, 2022) and comprises of fourteen chiefdoms namely; Lower Banta, Upper Banta, Timdale, Bagruwa, Kagboro, Dasse, Kowa, Kaiyamba, Kongbora, Kori, Kamajei, Fakunya, Ribbi and Bumpe. The ethnicity of the district is largely homogeneous with the Mende forming 60% of the population; the other ethnic groups comprise Sherbro, Temne and Loko.

2.1.2. Mano-Dasse Chiefdom

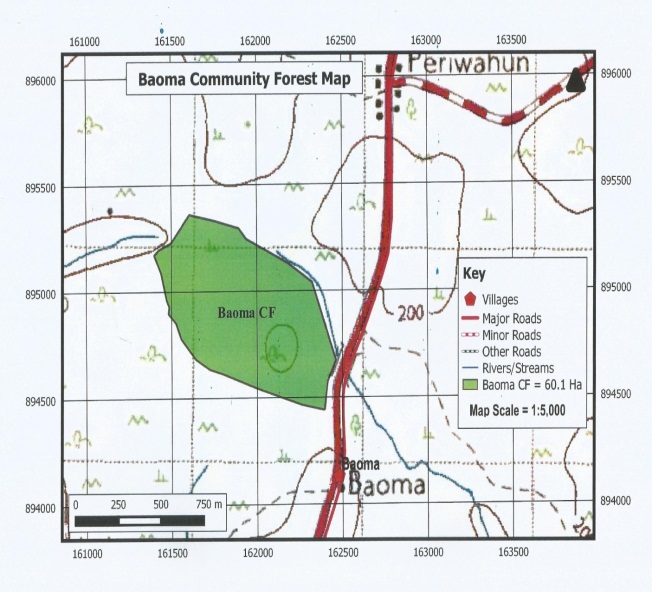

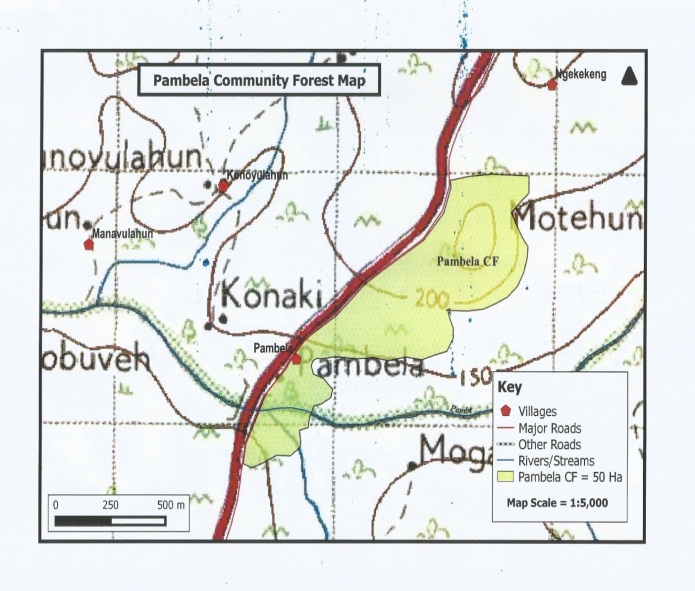

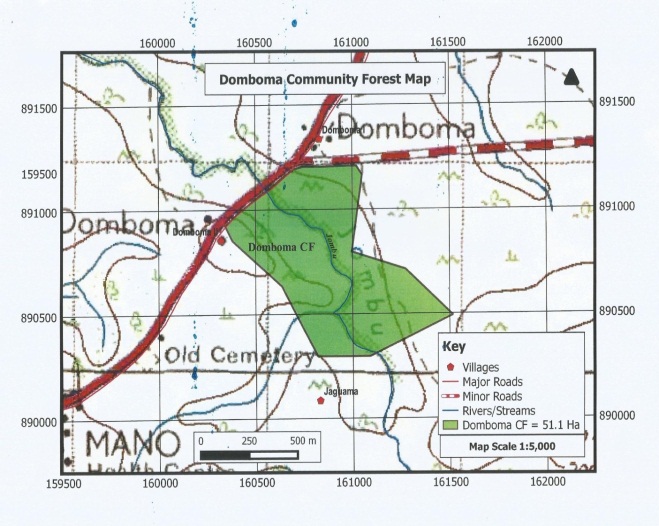

- Mano-Dasse is a Chiefdom in Moyamba district, located along the old highway from Freetown to Bo and accommodates the 3 communities (Boama, Domboma and Pambela) hosting the 3 community forests studied for this research. It has a population of 13,265, (Statistics Sierra Leone, 2021). The chiefdom is populated with both nationals and foreigners who migrated for business propose due to the existence of a train station at Dasse in the 90s; and some of these people stayed in the community after the closing of the railway station. However, the Mende tribe remains the most populated in the chiefdom, making the Mende language the dominant language spoken in the chiefdom. However, as krio is the most commonly spoken language in the country, many of the people in the chiefdom speak both krio and mende. The chiefdom is geographically divided into 14 administrative sections, they are: Domboma, Semabu, Foyia-Teawa, Mano Town, Jayiahum, Kenema, Neaty-Kiorie, Tanenihum-Konmor, Bongoyia, Taninihum-Kapuma, Youngifun, Babonbu Tommy, Temedi and Foyia-Gutpa. This study was carried out in the Domboma section which has eleven (11) villages (Mosheale, Kpaguma, Makambo, Moghah, Boama, Konovruhum, Batiama, Pambela, Domboma, Shahum and Dayma).As earlier stated, the 3 communities selected for this study were Boama, Domboma and Pambela. They are small contiguous communities with low human populations and majority of the people in each of the 3 communities were farmers; but the communities are rich in biodiversity and the traditional heads disallow commercial exploitation of forest products from their forests. According to sources at the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations-Sierra Leone (FAO-SL), these were some key factors for selecting them for the “Pilot Phase’’ of the FAO-SL Community-Based Forestry Management Project (CBFM). FAO-SL sources also confirmed that land areas reserved for CBFM in the each of the 3 communities are as follows; Baoma: 60.1 hectares (Figure 1), Pambela: 50 hectares (Figure 2) and Domboma: 51.1 hectares (Figure 3).

| Figure 1. Boama Community Forest Map (Source: FAO – SL) |

| Figure 2. Pambela Community Forest Map (Source FAO – SL) |

| Figure 3. Domboma Community Forest Map (Source FAO – SL) |

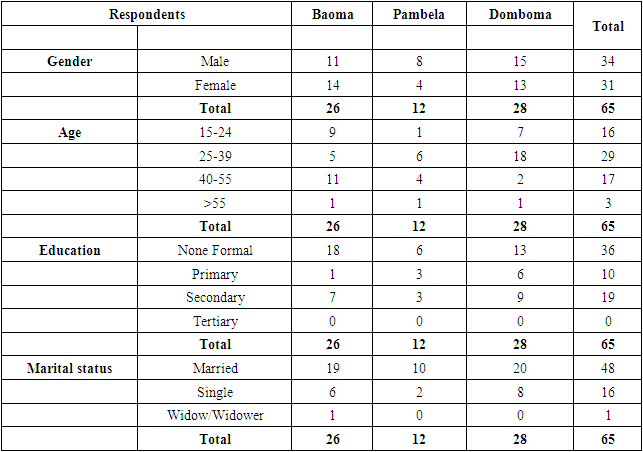

2.2. Sample Population

- According to the 2021 Sierra Leone Mid-term census, the population of Moyamba district was 346,771 - (167,836 male and 178,935 female). Dasse chiefdom had a population of 13451 (6700 male and 6751 female) and it is the 10th largest populated Chiefdom in Moyamba District. The Mid-term census data however did not include population figures at community levels, therefore prior to data collection for this study, a reconnaissance survey was conducted to collect preliminary information and to carry out a door-to-door household census of inhabitants of each of the 3 communities sampled. A total of 239 people, (adult males and females, youths, children and infants) believed to live in the 3 communities were counted. However, key respondent groups sampled for this study was categorized as adult male, adult female and youth (Male and Female). To further synthesize categorization of the stakeholder gropus, this study adopted the United Nation definition of Youth, (UN.org, 1981), which defines ‘youth’, as those persons between the ages of 15 and 24 years; was adopted for this study. Consequently, respondents from age 25 years and above were considered as adults.

2.3. Sample Size

- Results of the reconnaissance survey revealed that the cumulative population of both adults and youths in the 3 communities totaled 121 people. Therefore, due to the small human population size of the selected communities, 100% sampling intensity was targeted. However during data collection, only a total of 65 respondents were available for sampling; representing 54.16% of the target population. These comprised of 25 respondents in Baoma, 12 in Pambela and 28 in Domboma.

2.4. Data Collection

- Data for this research were obtained from both primary and secondary sources. Primary data were obtained using open and closed ended structured questionnaires to collect data from respondents. These contained uniform sets of questions to which respondents were subjected, therefore making their views to be analysed at the same level. Secondary data were sourced through desk study.

2.5. Data Analysis

- Data collected was analysed using descriptive analysis. Analysed data are presented here in, percentages, tables and graphs.

|

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results

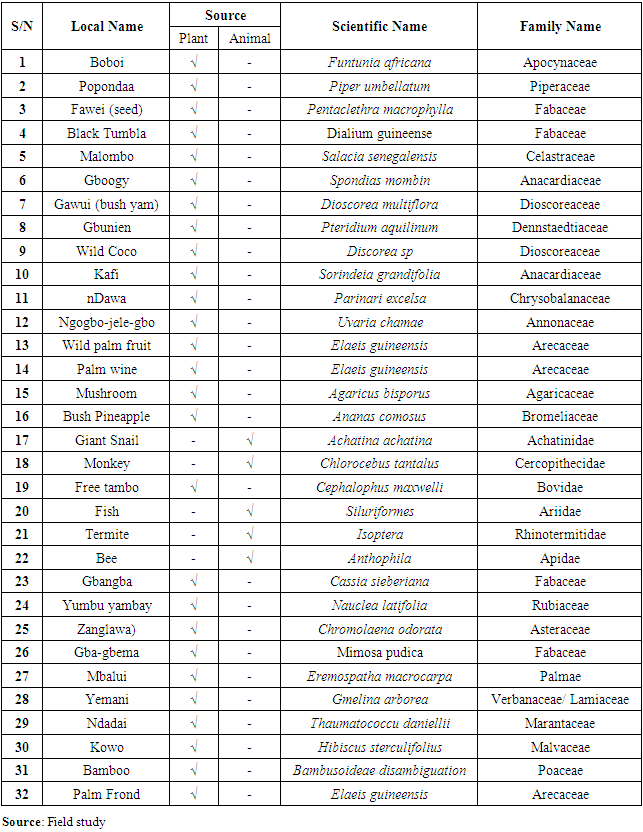

3.1.1. Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) Identified in the Three Communities Sampled

- Thirty two (32) NTFPs currently being used by respondents were identified, out of which about 84.40% and 15.60% were plant and animal-based respectively. The most represented families were Fabaceae (12.50%), followed by Arecaceae (9.37%) and lastly, both Anacardiaceae and Dioscoreaceae (6.25%). The NTFPs were identified by respondents using their respective local names (in Mende and/ Krio) and samples and pictures taken for subsequent scientific identification and clasification at the Njala university herbarium. A list of the identified NTFPs identified were clasified into their respective local, scientific and family names as seen in Table 2 below.

|

|

| Figure 4. Sources of Respondents Knowledge of NTFPs |

|

|

|

|

4. Conclusions

- i. Non-timber forest products identified and used by respondents were mostly from plant origin.ii. Family elders are the major sources of information on the importance of the importance of NTFPs in the communities studied.iii. NTFPs identified from both plant and animal origins were mostly consumed as food. iv. With existing strong forest governance in the communities sampled, there are prospects for the development of NTFPs; although income from this source could only be for alternative livelihood and not as major income source in order to maintain forest biodiversity and ecosystem integrity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors acknowledge the support and cooperation of local authorities in the communities where this research was carried out.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML