-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2022; 12(3): 79-101

doi:10.5923/j.ijaf.20221203.03

Received: Nov. 9, 2022; Accepted: Nov. 26, 2022; Published: Dec. 1, 2022

Challenges of Legal Instruments for Biodiversity Conservation along with National Parks

Md Rahimullah Miah1, Md Mehedi Hasan2, Jorin Tasnim Parisha3, Alexander Kiew Sayok4

1Department of IT in Health, North East Medical College and Hospital, Affiliated with Sylhet Medical University, (SMU), Sylhet, Bangladesh. and PhD Awardee from the IBEC, UNIMAS, Sarawak, Malaysia

2Department of Law, Green University of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3Government S.C. Girls’ High School, Sunamganj Sadar, Sunamganj, Bangladesh

4IBEC, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS), Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Md Rahimullah Miah, Department of IT in Health, North East Medical College and Hospital, Affiliated with Sylhet Medical University, (SMU), Sylhet, Bangladesh. and PhD Awardee from the IBEC, UNIMAS, Sarawak, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Biodiversity is the core outline when global environmental issues are discussed which responds to national environmental issues and interlinks with policy instruments. Environmental policy instruments are tools used by the state government to implement these conservation mechanisms through political commitments. The study aimed to assess the environmental policy instruments including legal for conserving of biodiversity through primary and secondary data analysis at Lawachara National Park (LNP) in Moulvibazar of Bangladesh. Key conservation legal instruments provided at the LNP and its challenges with gaps in policies for national parks management are highlighted. The study shows that the biodiversity related rules and regulations amended was highest in Bangladesh within the period of 2010 to 2020 while policy weight scoring is about 96% of LNP. The growth of national parks maximized within the same period. The study assessed that the existing legal conservation instruments are inadequate for national park biodiversity protection in Bangladesh.

Keywords: Conservation, Policy Instruments, National Park, Co-management, Bangladesh

Cite this paper: Md Rahimullah Miah, Md Mehedi Hasan, Jorin Tasnim Parisha, Alexander Kiew Sayok, Challenges of Legal Instruments for Biodiversity Conservation along with National Parks, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 12 No. 3, 2022, pp. 79-101. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20221203.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Policy instruments have a key role in improving the status of our environment. Environmental Policy Instrument is the process of placing environmental considerations at the heart of government decision-making on environmental issues among others includes loss of biodiversity, climate change and decrease ecosystem services. Biodiversity is the central agenda when global environmental issues discussed (CBD, 2010) with responds to national environmental issues and interlinks with policy instruments. Environmental policy instruments are tools used by state government to implement these environmental policies through national, regional and global commitments for national park biodiversity conservation. Bangladesh is a ratified state party of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which stated that by 2015, each state party should develop the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) as a conservation policy instrument according to Aichi Biodiversity Target 17 (CBD, 1992). Thus, Bangladesh developed the revised NBSAP towards national park biodiversity conservation for the long-term period (DoE, 2016). Moreover, the NBSAP is also the major mechanism for existing biodiversity protection to be made into national policies for each State Party to show how countries have responded to the UN agenda on sustainability (Ismail, 2012). The study distinguishes four basic types of policy instruments for biodiversity conservation: (a) Legal Instruments, (b) In-situ Instruments, (c), Informational Instruments, and (d) Ex-situ Instruments. The research relates to law and national park, so the choice of policy instruments is the first two in number instruments, which are legal and in-situ instruments. The study considers policy instruments through examining NBSAP to determine whether and how the NBSAP contributes to mainstreaming biodiversity across policy sectors using Clearing House Mechanism (CHM) in Bangladesh to halt biodiversity loss. Conservation of biodiversity within national parks requires rapid access to data such as the spatial and temporal distribution of species and their habitats within environmental context (Murray et al., 1997). Biodiversity is in the core field of environmental issues. The problem of loss of biodiversity has been raised as a very important global issue for several years due to the lack of dynamic policies, technological application, institutional support and stakeholder engagement (Miah et al, 2017). This study aimed to assess the environmental policy instruments including legal, in-situ and informational instruments for conserving of biodiversity through primary and secondary data analysis at Lawachara National Park (LNP) in Bangladesh, as a test site. The major consideration of this study is on the Lawachara National Park aspect including environmental, legal, policy and institutional frameworks for the conservation of biodiversity that are used by the co-management team in the National Parks of Bangladesh. In the context of the LNP, there are various challenges confronting biodiversity conservation and management policy initiatives and important including present status of existing policies (NFP, 1994), development of national park, rain water harvesting provisions, ecotourism management, removal of invasive alien species, stakeholders’ engagement and the application of conservation technology in the management of existing park. Conservation of biodiversity and its use in sustainable development have been impeded by many obstacles. The need to mainstream the conservation and sustainable use of biological resources across all sectors of the national economy, the society and the policy-making framework is a complex challenge at the heart of the Convention on Biological Diversity (Bashar, 2010). Various instruments are merged occasionally in a policy mix to tackle an assured environmental problem. These Environmental problems generally occur through overexploiting natural resources and mode of consumption of services and systematic products (Mickwitz, 2003). Rapid loss of biodiversity tends to be at the foremost of conservational issues as they potentially disturb the bio-systematic functions (Sachs et al., 2009; Kaeslin et al., 2012; Alamgir et al., 2014; Sohel et al., 2014). This loss of biodiversity is one of the most thoughtful global environmental apprehensions (dos Santos et al., 2015), which have been raised during various planetary precincts (Steffen et al., 2015) as a domineering worldwide issue for several years. Everyone exploits biodiversity but none can conserve it due to lack of dynamic policies, institutional supports, stakeholders’ engagement, and ecotourism services, control measure of invasive alien species and application of conservation technologies. Thus, appropriate and specific policies are required to curb rapid losses of biodiversity. National Parks (NPs) are often targeted on lands with the least political resistance to their establishment, and thus typically face the least anthropogenic threat. Due to lack of sound assessments can cause significance for the understanding of biodiversity related update rules and regulations for development of indicators and indices, which permit changes and trends to be observed and transformed over time. To date, there is no up-to-date comprehensive model developed incorporating the diverse pertinent political, environmental, socio-cultural, technological, economic, institutional and legal processes for National Park Biodiversity Management. The study highlights on stimulating sustainable use of ecosystem to incorporate most of these components including involvement of stakeholders, institutional participations, update policy integrations, and conservation technologies. This research illustrates to conservation of biodiversity for LNP management with indispensable tools for studying changes of conservation systems and their impacts in order to provide justifiable policy options. These study objectives are to assess the implementation of environmental policy instruments, namely legal, in-situ and informational instruments for conservation of biodiversity in Bangladesh.

2. General Context on Legal Instruments

- Legal instrument directly controls or confines ecologically detrimental actions by authorising the reduction or restraint (Hahn et al., 1991) of damaging activities. Legal instruments aim at modification of the set of options open to agents. The use of this instrument has been the most common public intervention approach in the environmental policies of ratified CBD State Parties. This approach is often called “Command-and Control” with varying degrees of justification (OECD, 1994). The main legal instruments are well known and include law, policy and strategic plan as well as some government orders, schedules and directives (Ackerman et al., 1985). While it often lacks the tractability and efficacies related with direct conservation-based tactics, it offers an effective means of unpromising the intractable (UNEP, 1992), the inept, or the uncompromising, who may demonstrate insensitive (Skelton et al., 1995) distribution to educational, motivational, property right, informational, intentional, and price-based instruments. The legal systems in the conservation instruments may also be requisite to reserve the possibility of other relevant instruments (Bardach and Kagan, 1982). Moreover, regulatory instruments may be discriminatory, and are difficult to revise as new information becomes obtainable. However, some positive legal management enhance necessary to protect biodiversity from undomesticated animals and other threats. According to Article 18A of the National Constitution of Bangladesh, the objective is to the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) encourage safeguarding and recovering the environment and to protect as well as to secure the natural assets, biological diversity, forests flora and fauna and other relevant areas for the current and upcoming nations (TCPRB, 2012). Therefore, the GoB produced the Wildlife Conservation and Security Act 2012 including legal instruments and protection systems, but no legal instruments for the protection of undergrowth species effectively, although these species is a part of national park biodiversity.

2.1. Aichi Biodiversity Targets and National Conservation

- Aichi Biodiversity Targets (ABT) included 20 targets for conservation of national biodiversity (UNEP-WCMC, 2015) within stipulated time 2020. The Article 17 of ABT indicated that every state government of CBD should improve and to approve a strategic policy instrument for effective conservation action plan within 2015 (ABT, 2010a), which was shared to this government in 2010 through at Nagoya supplementary program (Leadley et al., 2014; CBD, 2010). Aichi Biodiversity Targets–ABT (2011-2020) are enhancing indicators for national biodiversity conservation (CBD 2016a), which indicates to the global networks. Aichi Biodiversity Targets contains five strategic goals including existing targets in connection with sustainable development goals (CBD-SDG, 2016; United Nations, 2015). The specific objectives of these targets are mentioned as sequentially, such as: (a) to achieve and utilize the all flora and fauna sustainably, legitimately, and implementing ecological-based (Rice, 2016) policies (CBD, 2010a), (b) to recognise species invasions for regulatory or eliminating as a prioritised basis of national park biodiversity conservation within stipulated time (CBD, 2010b), (c) to conserve 17% of landscapes and 10% of seascapes areas’ biodiversity (CBD, 2014) associated with operative reserved area-based protection, (d) to progress and implement national conservation strategic plan of each state government within the period of 2015, (e) to develop and implement the science and technology management connecting to national park biodiversity status and its consequences through transferring, feedback sharing and recovery measures.

2.2. Biodiversity Strategic Plan- Evidence based Policy

- National Biological diversity policy plan is an evidence-based policy instrument. There is relation between evidence base and policy coherence (Segan et al., 2011) for incorporating values into NBSAP (Chenery et al., 2015)., such as (a) Incorporating values into NBSAP (CBD Secretariat, 2010), (b) Integrated NBSAP’s rationale, objectives and insights on values of nature, (c) Internalise and integrate biodiversity values and concerns, (d) Mainstream biodiversity, and (e) Behavioral changes (Schneider and Ingram, 1990), which demonstrate the value of revised NBSAP for national outcomes, improved human wellbeing and halt biodiversity loss (Adams and Sandbrook, 2013). Lack of effective and target-oriented strategic plan, conservation of national park biodiversity tends to losses profoundly. Because, national biodiversity strategy and action plan connect with goals, targets and actions for effective conservation.

2.3. National Forest Policy and Conservation of Biodiversity in Bangladesh

- The adoption of authorised laws and regulations through national park management tends to State rules for conserving of biodiversity and its protection (Alam, 2009) towards national parks. According to State Forest rules, the Government accelerated approximately 20% of forest cover through afforestation program within 2015 for maintaining ecological balance. This attempts represented with flora and fauna in the core areas of national parks, particularly in Sylhet division for increasing massive ecotourism, raising awareness on environmental conservation and mitigation of climate change (Bose and Muller-Ferch, 2008). However, the Bangladesh Forest Department could not fulfil the targets within the stipulated time. For this reasons, the Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh takes initiative for update National Forest Policy (draft) 2016. This new policy will open the door for biodiversity conservation towards national parks to fulfil the Aichi Biodiversity Targets 2020 of CBD.

2.4. National Forest Act and Biodiversity Conservation

- Government of Bangladesh amended the Forest Act 2000. It is the major legal instrument in national forestry sector. The Forest Act was modified in accord through the straightforward provisions of misuse and security, and took little reflection towards participating features of national park biodiversity protection. Overall, the amended forest law takes reticent several of the scarce Articles of the innovative law and administration. It silently affords area for the implementation of the traditional managing attitudes through the Forest Department (Muzaffar et al., 2011). These legal instruments have influenced towards national and international policy frameworks with diverse contexts of participatory forestry practices, particularly biodiversity conservation at national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, and special conservation areas in Bangladesh. The existing engagements in the announcement of national parks and the outlines of collaborative administration in the reserve forest are closely connected to the primer and extension of shared forest options (MoEF, 2005).Some major problems were identified by different sources at Lawachara National Park (LNP) in Moulvibazar district of Bangladesh (IPAC, 2012). These are: (i) Lack of demarcation for national park boundary, (ii) Lack of national parks integrated online database, Biodiversity Clearing House Mechanism (BCHM) and digital conservation apps, (iii) Lack of sectoral integration effectively, (iv) Illegal logging, forest land encroachment and political nepotism in co-management team (v) Less involvement of local and indigenous communities towards ecotourism activities, (vi) Lack of awareness on environmental education, (vii) Lack of wildlife security and misuse modern technology (Kays et al., 2011) (viii) Excessive invasions of alien species at LNP. (ix) Associated food shortage for wildlife (Deshwara and Eagle, 2017; Bdnews24, 2016). (x) Animal is susceptible to traffic accidents in Lawachara National Park (Deshwara and Eagle, 2017). Lack of determined policies, national park biodiversity estimated to decline by a supplementary 10% of internationally within the period of 2050 (OECD, 2012). Previous research failed to reveal the strong points and faults evidently lingering to complications (Kaomuangnoi, 2014) on environmental policy instruments including National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) evaluation towards national parks implementing policy domains with monitoring, formulation and analysis. Biodiversity technological research becomes more challenging due to lack of proper applications of information systems for digital conservation in Bangladesh. Developing state party lacks proper information and evaluation related to biodiversity conservation systems (Heywood, 1997) on national park.

3. Methodology

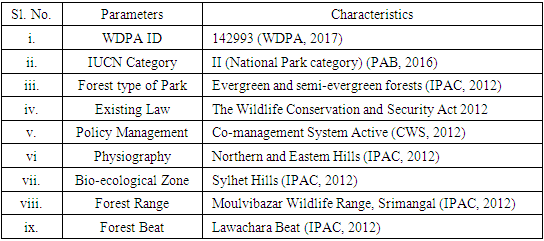

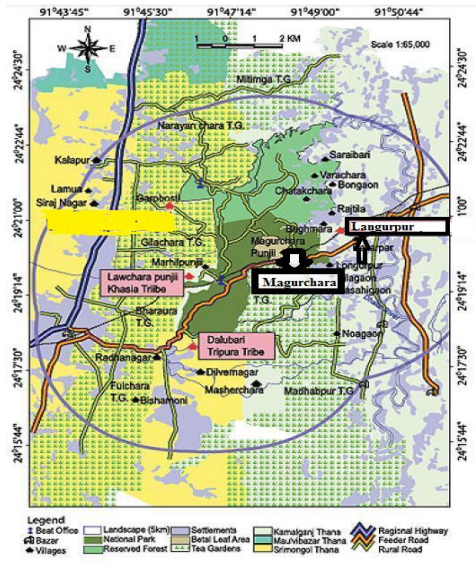

- Bangladesh is a developing country in the north-eastern part of south-east Asia with augmented biodiversity earlier (DoE, 2016) and lies in the earth largest deltaic area between the coordinates of 20°34' and 26°38' north latitude; and 88°01' and 92°41' east longitude (DoE, 2016). The study was undertaken at Lawachara National Park (LNP) at Kamalganj sub-district in Moulvibazar of Sylhet division, Bangladesh coordinates with 24°32′12″N 91°47′03″E (NSP, 2005) as the forest conservation case study site. The LNP is situated in the Union and sub-district Kamalganj (Figure 1) in Moulvibazar district of Bangladesh (MP, 2006) with indicated parameters as shown in Table 1.

|

| Figure 1. Lawachara National Park at Kamalaganj in Moulvibazar, Bangladesh (Source: Ferdous, 2015; NSP, 2007; MP, 2006) |

3.1. Legal Status

- Lawachara National Park (LNP) was established through the President Order under the Bangladesh Forest Act 1927 (Amendment 2000). In 1996, the LNP was declared as a National Park under the provision of Article 23 (3) of the Wildlife (Preservation) (Amendment) 1974 (Hossain, 2007; NACOM, 2003). It was declared as a National Park in 1996 with 1,250 hectares (Gazette Notification-PBM (S-3)7/96/367 on 07 July 1996) (Halim et al., 2008) with highly diverse hilly evergreen forest under the conservation status of the Wildlife Preservation Act-1974 (this Act revealed). The current Wildlife Conservation and Security Act, 2012 is effective under the Article 18A of the National Constitution of Bangladesh.

3.2. Biodiversity Status

- The LNP is one of three national parks in Sylhet region in the north eastern part of Bangladesh (RIMS, 2015). It is semi-evergreen and mixed deciduous forest. Total 460 species consist of floral 167 and 293 faunal species including amphibian 4, reptiles 6, birds 246, mammals 20, insect 17 (IPAC, 2012; Jalil, 2009). Major plant species are Chapalish, Gorjon, Jarul, Rokton, Segun and major wildlife species are Macaque, Barking deer, Capped Langur (NSP, 2006). The Lawachara is the most suitable to tourists to watch the stunning Hoolock Gibbon (Bunipithecus hoolock / Hylobates hoolock)), Capped Langur (Trachypithecus pileatus), Phayre’s Langur (Trachypithecus phayrei), Pigtailed Macaque (Macaca nemestrina), Orange-bellied Himalayan Squirrel (Dremomis lokriah), Barking Deer (Muntiacus muntjac), Masked Civet (Paguma larvata) and rare Cobra and Python species (NACOM, 2003; Hossain, 2007). The LNP is an attractive ecotourism destination due to its aesthetic scenary and dense forest diversity (NSP, 2006). The Park was also a hotspot for biodiversity to find several species of a new and regional record for biodiversity conservation of Bangladesh (Hossain, 2007; Rufford, 2014).

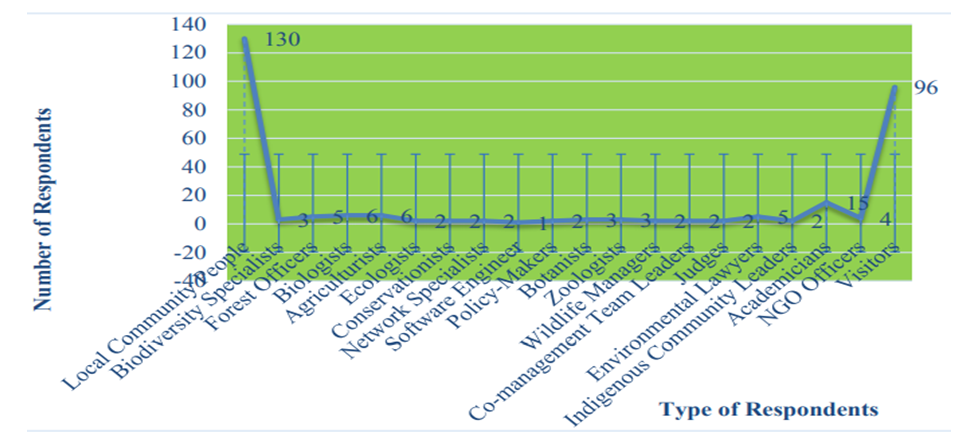

3.3. Legislation Scoring Method

- Legislation scoring was calculated for development of update law, policy, order and related schedule for biodiversity protection effectively with the certain period in Bangladesh.

| (1) |

3.4. Data Collection and Handling

- At first, all the general information regarding the occurrence of biodiversity and informatics including biodiversity conservation systems in the Lawachara National Park and their diversity, status, and distribution are collected and tabulated in an organized manner. After the data had been collected, they were checked properly for accuracy, by using the crosschecking method for data compilation.

3.5. Data Analysis, Presentation and Interpretation

- All general information regarding the occurrence of biodiversity and national parks including legal systems in the protected area and their diversity, status and distribution were checked for accuracy from the different sources and sources of information were also verified. Information regarding the initiatives of the authority towards the conservation of biodiversity was collected through relevant secondary information and field survey. Then the information were included in the preparation of data master sheet and incorporated into convenient forms used in the result and discussion section. The data were compiled and analyzed for presentation and interpretation using standard data analysis software like MS Office Suite 2013, and R programming version 3.4.

4. Results

- Environmental Conservation Policy research findings are about developed models to evaluate the contribution of environmental policy instruments along with information systems for biodiversity conservation towards National Parks in Bangladesh. The management of biodiversity by security representative and well-connected habitat network in managed national parks. The park requires a wise combination of protection, maintenance, and restoration of plants, animals and habitat at sustaining goals (Angelstam et al., 2003). The ultimate goal of this research is to evaluate the existing laws, policies, assessment of biodiversity information systems with clearing house mechanism and stakeholders’ engagement, control measures of invasive alien species and conservation strategies, which illustrates in different section of this chapter successively.

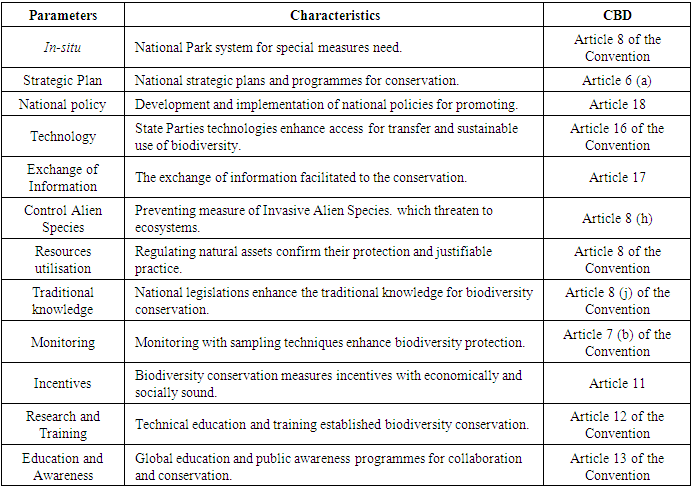

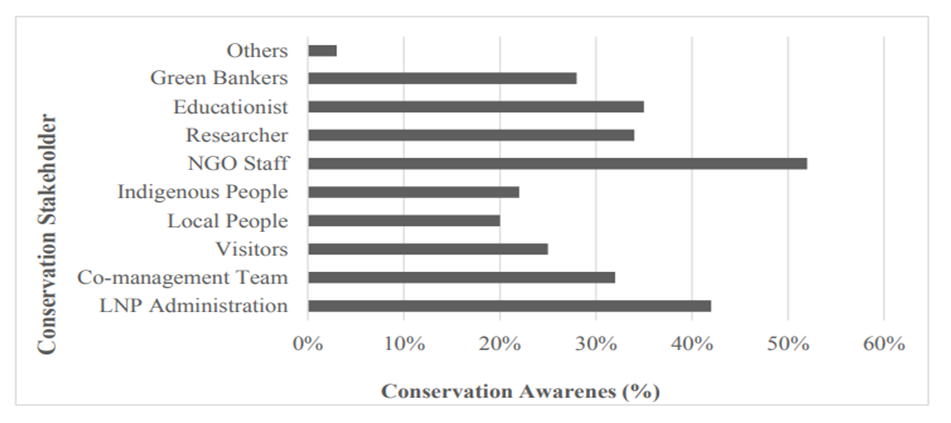

4.1. Conservation Awareness among Stakeholders

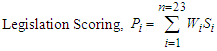

- Socio-economic features enhance to identify the different parameters of stakeholders for cooperation and management of National Park biodiversity, as shown in Figure 2. The graph represents different types of stakeholders who responded in the research activities.

| Figure 2. Quantity of Stakeholders Respondents |

| Figure 3. Conservation Awareness of Diverse Stakeholders |

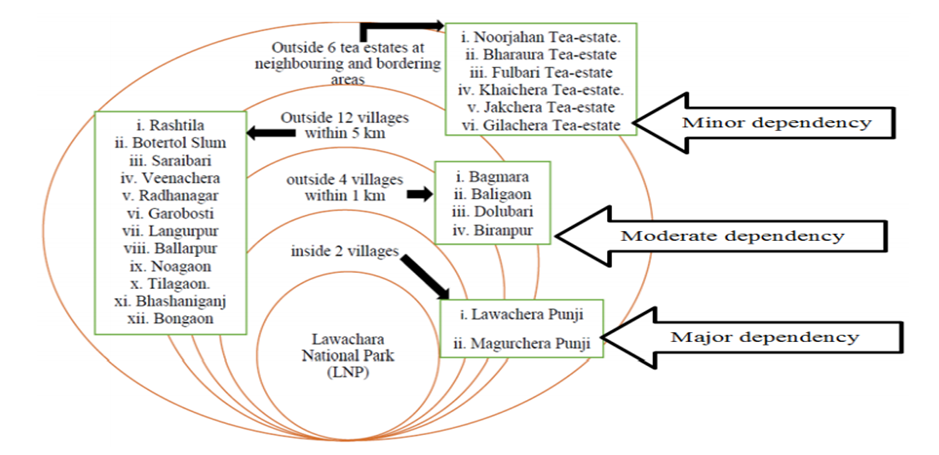

4.2. Impact of Settlements on Lawachara National Park

- Settlement has been one of the main footprints of humanity on earth’s terrestrial ecosystems (Massada et al., 2014). Lawachara National Park (LNP) surrounded by 18 villages, tea-estate, agricultural land and barren land. In this LNP, there are numerous interactions between human and natural resources as a bio-ecologically region in Bangladesh. Lawachara National Park is the park area in which human settlements adjoin or intermix of local and indigenous communities with bio-ecosystems. These human settlements affect neighbouring ecosystems through biotic processes including introduction of exotic species, wildlife subsidization, land encroachment, disease transfer, land cover conversion, fragmentation, and habitat losses. The effects of LNP settlements on biodiversity conservation are two tiered– starting with national park modification and fragmentation by railway route and vehicle road, and progressing on different processes in which direct and indirect effects of anthropogenic activities spread into neighbouring ecosystems at varying fluctuate scales. The people of these villages are dependence on LNP including major, moderate and minor primary stakeholders according to involvement and distance, which as shown in Figure 4. The study identified the following outputs:(a) Major dependency villages: Bagmara, Magurchera, Lawachera, Baligaon, Dolubari and Biranpur. These villages are situated within 1 km surrounding LNP. (b) Moderate dependency villages: Rashtila, Botertol Slum, Saraibari, Veenachera, Radhanagar and Garobosti; (c) Minor dependency villages: Langurpur, Ballarpur, Noagaon, Tilagaon, Bhashaniganj and Bongaon.

| Figure 4. Settlement villages covered Lawachara National Park’s inside and adjacent Area |

|

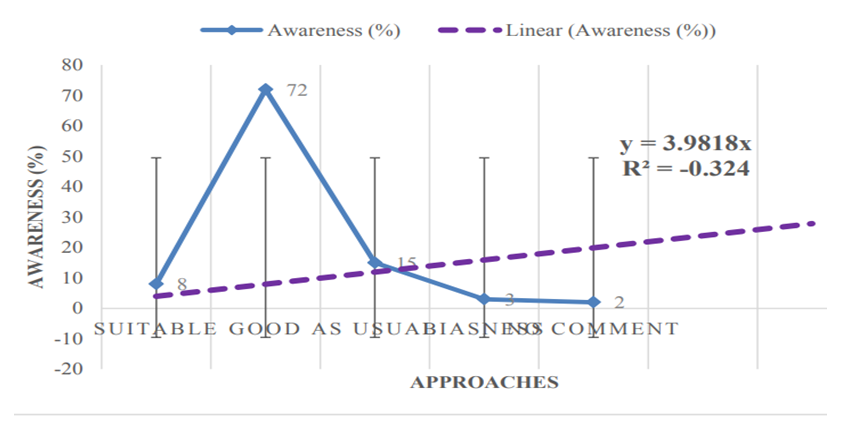

4.3. Awareness on Co-Management Approach

- Co-management approach is the new system for National Park biodiversity management through community involvement, as shown in Figure 5, with trend lines graphs. Awareness on co-management approach at studied national park area of Bangladesh in the scheduled period can be estimated using the equation developed through regression analysis. Here, the study expressed the approach through the following equation,

| (2) |

| Figure 5. Awareness on Co-management Approach |

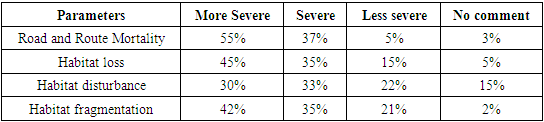

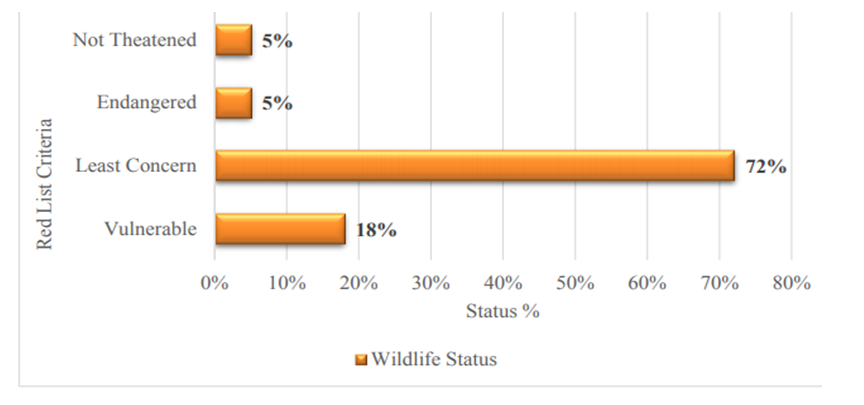

4.4. Wildlife Critical Condition of Lawachara National Park

- From the field observation, sheltered wildlife status of Lawachara National Park (LNP) is captured by threats. These Threats to wildlife and their habitations are multifarious and pervasive in the Lawachara National Park. According to IUCN (2017) these are 39 mammalian wildlife consisted in LNP, out of them, almost 23% of the known species are threatened, 18% are vulnerable as well as 5% endangered, which as shown in Figure 6. The study showed the status of vulnerable and endangered of wildlife conservation in the LNP with risk assessment. Some wildlife of LNP were killed by Railway and vehicles during movement the road / route (SOD, 2016).

| Figure 6. Wildlife Criteria of Lawachara National Park |

|

| Figure 7. Snake and Monkey attacked by vehicles at Lawachara National Park road (Babu, 2013) |

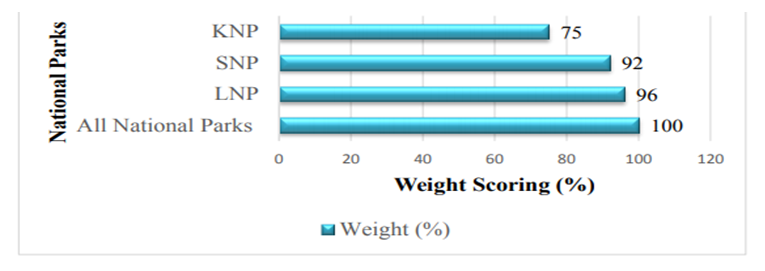

4.5. Biodiversity-Related National Legislation Scoring

- The legislation scoring categories and their grading definitions constructed based on discussions with biodiversity and legal experts including both professionals and academicians in Bangladesh context, as shown in Figure 8. The graph observed maximum weight (%) in Lawachara National Park (LNP) and minimum in Khadimnagar National Park (KNP), where compare with linear, and polynomial trend line for dissemination of present status on legislation scoring. The score of National Park increased gradually. The findings suggest that the Government of Bangladesh targets of fully implementing the biodiversity related policies/laws/ legislations till to date remains substantially unattained. From the study, biodiversity related law, policy, and administrative order etc. produced more or less in several years, but no legislation produced from the period of 1980 to 1989 in Bangladesh.

| Figure 8. Biodiversity Conservation related existing national legislation scoring |

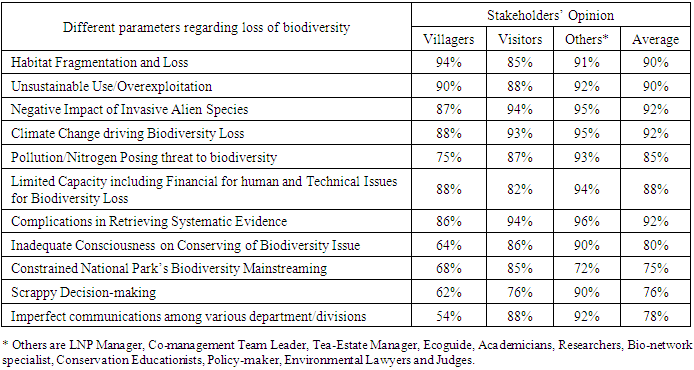

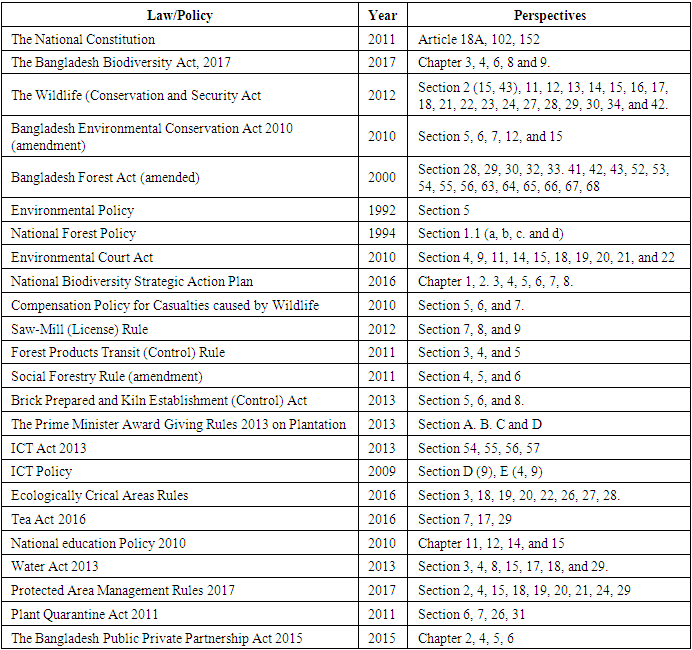

4.6. Existing Law and Policies Related to Biodiversity Conservation

- Existing legislations related to biodiversity conservation, as shown in Table 4, with relevant parameters. The study relates to biodiversity conservation with different articles at the Constitution of Convention on Biological Diversity, such as in-situ, national policy, strategic plan and relevant technology. Every state party develops National Park, national biodiversity related policy and strategic plan through national biodiversity database and clearing house mechanism according to CBD requirements. These requirements enhanced to legislation analysis for conservation of biodiversity towards National Parks in Bangladesh on the priority of regulation, control alien species, regular monitoring through effective research and training, environmental education awareness and sustainable use.

|

4.7. Legislation Relevance to Biodiversity conservation in Bangladesh

- New legislation relevance to biodiversity conservation initiatives require human resources, institutional capacity, and funding for successful development and implementation to identify the people and organization with the interest and expertise to ensure progress on new legislation development related to biodiversity in Bangladesh (Table 5).

|

| Figure 9. Criteria on Conservation Policy Improvement |

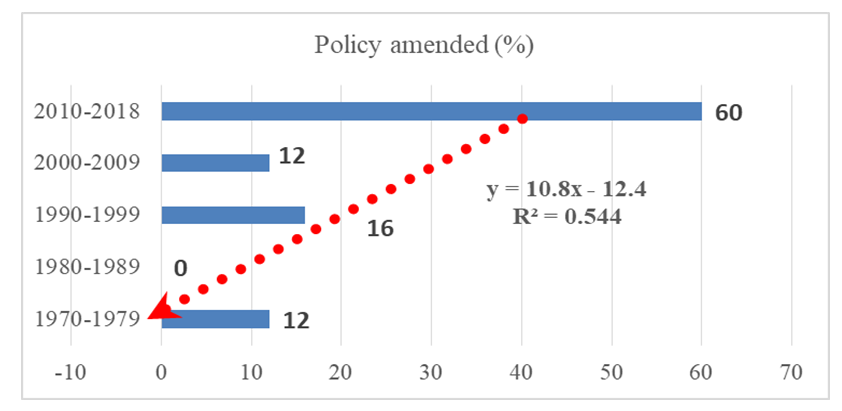

4.8. Produced Quantity of National Legislations

- National legislation develops for enhancement of national biodiversity towards National Parks. Biodiversity related national legislation produced maximum within the period of 2010-2018, as shown in Figure 10. The study found that most of legislations related to biodiversity conservation formed after COP-10, in this period, CBD provided circulations to the state parties for update the national legislation for conserving of biological diversity. The Government of Bangladesh produced the Wildlife Conservation and Security Act 2012 within this period. The study suggested that the government takes initiatives for separate law and policy for national biodiversity conservation towards national parks in Bangladesh.

| Figure 10. Produced Number of Biodiversity related Legislation in Bangladesh |

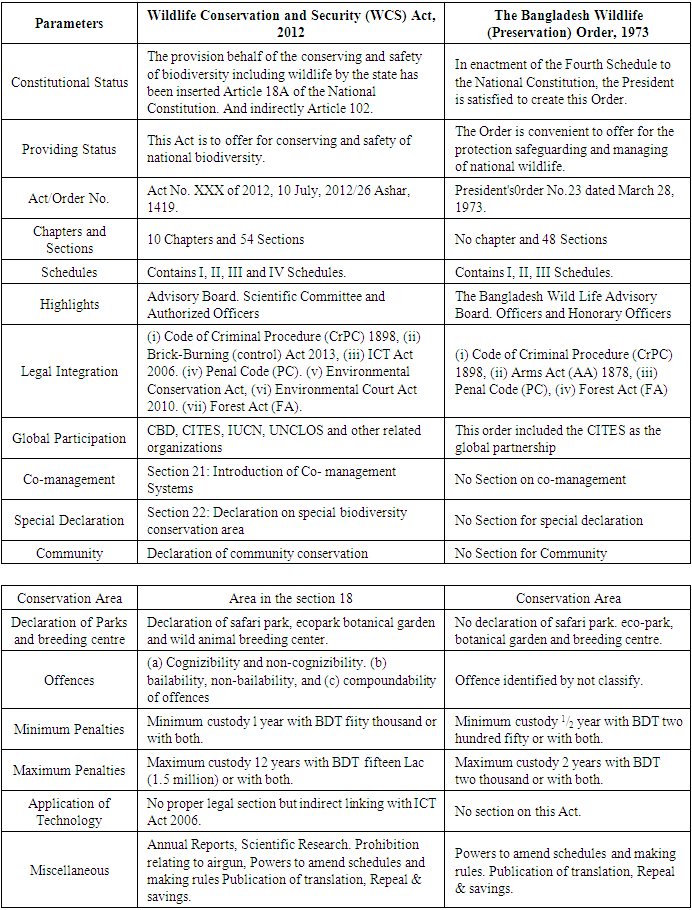

4.9. Analysis of Wildlife Conservation Act and Order

- National biodiversity conservation opens the door through the Wildlife Conservation and Security (WCS) Act 2012. This Act updates in Bangladesh for biodiversity conservation and protection, particularly wildlife protection. The WCS compares with previous Preservation Order 1973, as shown in Table 6. The main parameters highlight on National Constitutional Status, Legal Integration, and National Park declaration, Co-management System, Penalties, Biodiversity Advisory Board and Scientific Committee. But no Section of relevant Law and policy mentions for digital conservation through National Park database and clearing house mechanism. From the respondent’s opinion on WCS Act 2012 at FGD is as 11% ‘adequate’, 33% ‘good’, 56% ‘inadequate’ and 2% ‘no comment’. The findings suggest for modification with new Sections related on digital conservation, particularly biodiversity information systems and clearing house mechanism for the purpose of global network connection and digital conservation. The study also represented the legal status of co-management system in Section 21 of the Wildlife Conservation and Security Act 2012 creating new opportunities for national park biodiversity conservation in connection with national and global perspectives.

|

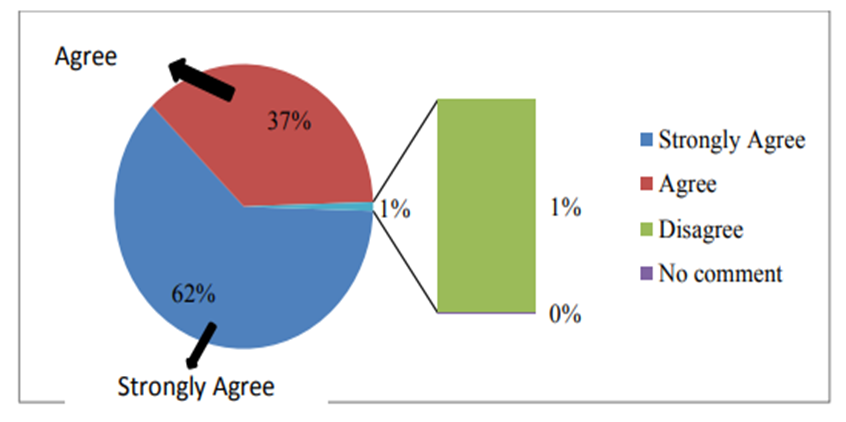

4.10. Essential Law and Policy Adoptions for National Park

- National Park is an essential In-situ instrumentsns for biodiversity conservation. Every State Party committed to CBD to increase the National Parks with the stipulated times. For this purpose, each State Party tries to adopt relevant law and policy. Most (62%) respondents ‘strongly agreed’ for essential law and policy adoption for National Park management, on the priority of Aichi Biodiversity Targets 2020, as shown in Figure 11. The findings suggest that Government should adopt the priority of stakeholders’ opinions for development of new essential law and policy for National Park management.

| Figure 11. Stakeholders’ opinion on essential laws and policy adoption for national park |

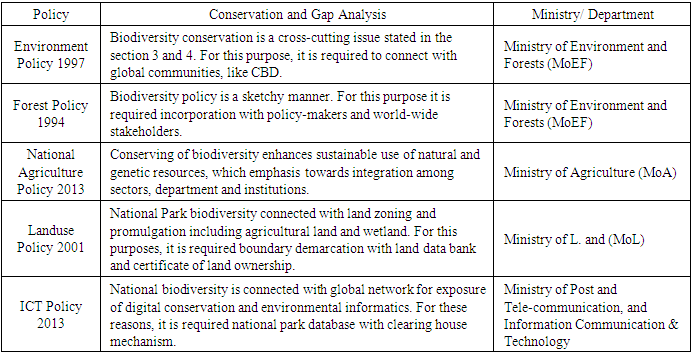

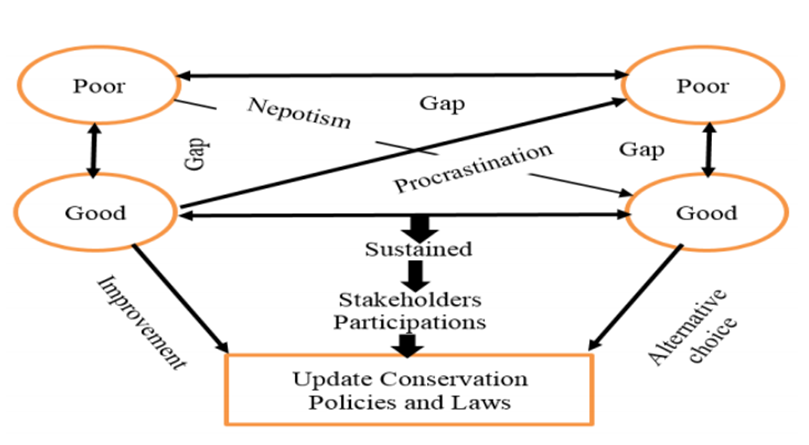

4.11. Conservation-Related Policy and Gap Analysis

- Biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people are common heritage and humanity’s most important life-supporting ‘safety net’ (Sandra Diaz, 2019). This safety net connects with conservation policies. Conservation related policies contain some gaps on biodiversity protection, effective management, cooperation, coordination and integration among various sectors/departments. The MoEFCC in Bangladesh leads the position for integration and development of NBSAP, CHM and National Park management and forestation programmes, as shown in Table 7, successively including relevant policy, ministry or department and conservation related gaps. As a State Party, Bangladesh has little research on biodiversity policy and technology, where there are a lot of research gaps. In this regard, gaps are observed between update policy and application of biodiversity technology. The research finds suitable methods on the priority of observing gaps. The study suggests enhancing the revised edition of NBSAP towards National Park’s biodiversity conservation. Nature conservation related policy and gap analysis discussed in Chapter 5 in details including policy options, policy integration, policy improvement and combination of conservation policy and technology for Lawachara National Park Biodiversity Management. The study also suggests that the integration of natural and social sciences in the form of two-dimensional (horizontal and vertical) gap analysis is an efficient tool (Angelstam et al., 2003) for the implementation of biodiversity policy.

|

5. Discussion

- The discussion on analysis of research findings on environmental policy instruments, along with the assessment of information systems evaluates the biodiversity conservation at Lawachara National Park in Bangladesh. Result of this study clearly demonstrates that ‘In-situ’ environmental conservation policy instrument is more suitable than legal and informational instruments for biodiversity conservation. Limited comparison of legal and informational instruments suitably have been undertaken and conclusions differ. In this study, the development of produced policies declaration of National Parks and applications of biodiversity clearing house mechanism were analysed as criteria for suitable biodiversity conservation. The three mentioned environmental conservation policy instruments analysed had different effects on National Park Biodiversity Management, Policy Development and application of digital conservation of Bangladesh – as a signatory State Party of CBD’s objectives requirements. The findings on the existing policy instruments are inadequate in connection with national and global perspectives, where there are some gaps, like policy formulation, sectoral integration, national park declaration, establishment of digital conservation.

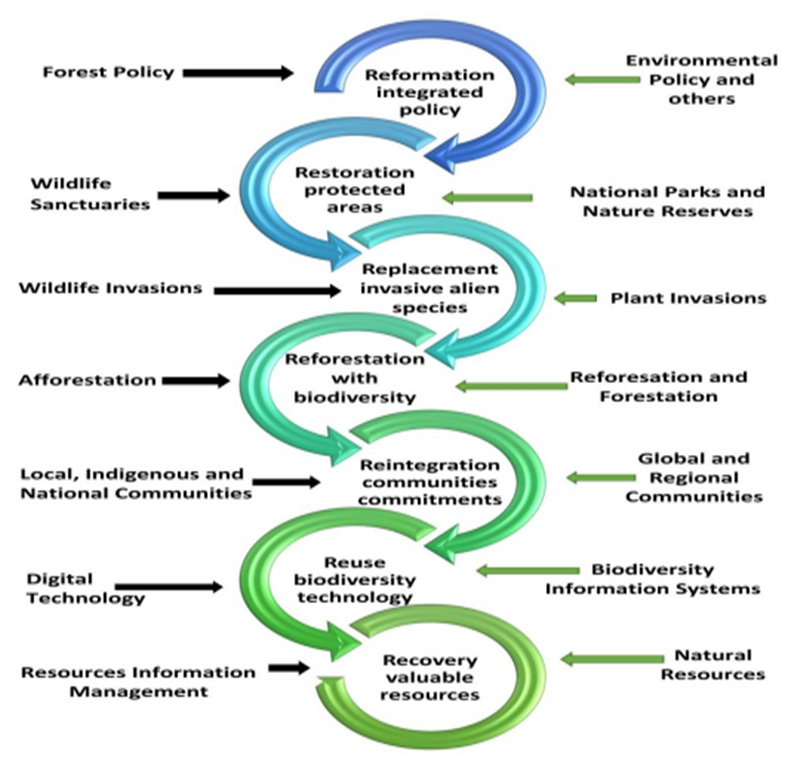

5.1. Develop 7R’s Policy for National Park Biodiversity Conservation

- Conservation policy is the recognition of the rights of nature in the ‘Rights of Mother Earth’ law (Romero-Muñoz et al., 2019). The 7R’s Policy is essential for national park biodiversity conservation. Here includes seven parameters rule indicating first letter capital “R” as shown in Figure 12, such as: (i) Reformation integrated policy in connection with forest policy, environmental policy and relevant other policies, (ii) Restoration national parks, (iii) Replacement Invasive Alien Species (including plant invasion and wildlife invasion), (iv) Reforestation with biodiversity targets indicates on afforestation for forestation on the priority of Aichi Biodiversity Targets 2020, (v) Reintegration communities commitment (i.e. they are mainly local, indigenous and national communities as well as regional and global communities), (vi) Reuse biodiversity technology i.e. application of digital technology and biodiversity information systems, (vii) Recovery valuable resources (i.e. using resource information management systems for protection of natural resources). The 7R’s policy improves the national policy reforms and enhances to development of BCHM, particularly Lawachara National Park Database linking with reformation, restoration, replacement, reintegration, digital conservation and resource recovery.

| Figure 12. 7R’s Policy Theme for Conserving of National Park Biodiversity |

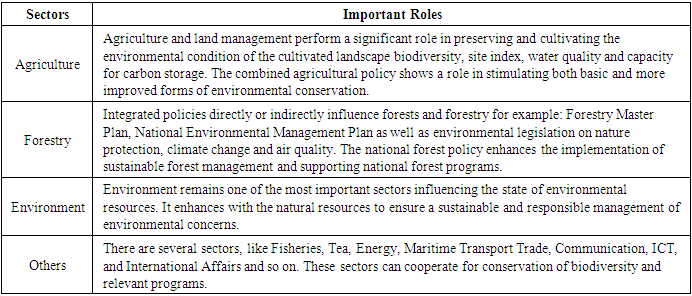

5.2. Departmental Policies Integration for conservation of National biodiversity

- Bangladesh is a developing country, consists of different sectors and departments, like Bangladesh Forest department, Department of Environment, Department of Agriculture and so on. Each sector has individual policy, viz. forest policy, agriculture policy, environmental policy, and land policy etc., as shown in Table 8, with necessary examples. There is a shared important link among these sectors for sustainable development, social and economic reforms and their integrations for specific policy areas (Owens and Hope, 1989). From the point of research, biodiversity policy relates with public policy, which is related to National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP). Article 6 of the CBD requires each State Party to develop a NBSAP for implementation of the Convention’s objectives, to integrate the plan’s objectives into sectoral policies and to report to other Parties about related efforts, successes and failures (CBD, 1992). Government of Bangladesh adopted a NBSAP to halt the loss of biodiversity in Bangladesh and to reconcile protection with the interests of users (DoE, 2016). The National Strategy is based on the CBD’s biodiversity strategy; with connect to a number of related national sectoral strategies inter alia National Conservation Strategy, the Country Perspective Plan and linking within the Sustainable Development Goals.

|

5.3. Challenges for Dynamic Conservation Legal Instruments

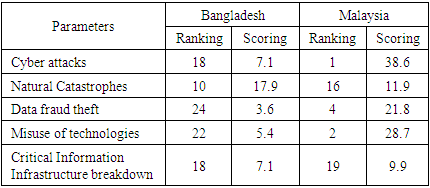

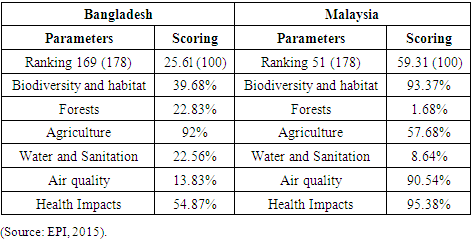

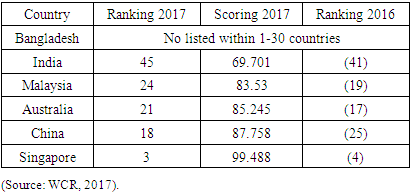

- The prominence of biodiversity and healthy ecosystems for the country’s supportable economic and social development is largely standard, but this awareness is not yet broadly replicated in the planning, formulating and implementation of policy procedures and corporate decisions (GIZ, 2019). Bangladesh faces a number of challenges for empirical dynamic policies. Mainly, it is alarming that matters such as federal policy can be effectively executed at the State Government and department levels in Bangladesh; it would to need sectorial/departmental policies integration. According to Global Risks Report (2016), Malaysia is more risks country on cyber-attacks, but Bangladesh is more vulnerable on natural catastrophes than that of Malaysia which as shown in Table 9. On the other hand, Malaysia developed online biodiversity clearing house mechanism (BCHM) according to CBD’s requirements; till date, the BCHM is in on-going process in Bangladesh.

|

|

|

5.4. Environmental Policy Instruments towards Sustainability

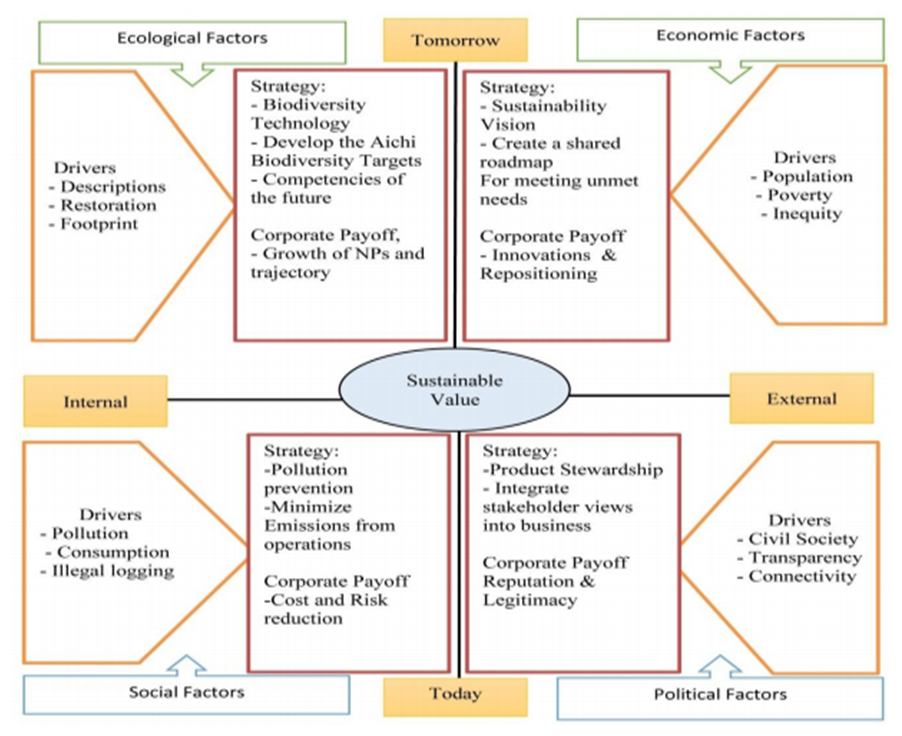

- Environmental development is a pre-condition for green economy, which is a crucial challenge for sustainable biodiversity in Bangladesh (BER, 2016). Because, efforts are on to integrate issues pertaining to environment with mainstream development policies to ensure economic growth and environmental sustainability. Moreover, sustainability depends on 17 goals of Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), such as: poverty, food, health, education, women, water, energy, economy, infrastructure, inequality, climate, consumption, habitation, marine ecosystem, ecosystem, institution and individual’s sustainability (UN, 2015; MoEF, 2016). Grant for research activities is largely dependent on donors (for example global-GEF, UNDP, USAID; national- ICT division), although national cash and in-kind contributions are significant. Although a certain level of national subsidy is likely to continue to be made accessible, international financial mechanisms to reimburse for the predetermined use of national park needs to be further settled. Such alternative funding mechanisms are under development by the national or regional research project executing agencies for bioenvironmental conservation towards national parks management. This research provides a good overview on biodiversity conservation system, growth of national parks, comparative analysis on CHM and NBSAP for the present and upcoming generations’ sustainability. Payment for ecosystem services (PES) is among the advocated viable options on developing returns from sustainable economic activities, such as national park biodiversity conservation through rainwater harvesting or ecotourism development. Corporate social responsibility funds from private companies (for example- HSBC, Dutch Bangla Bank) are an increasingly important complementary sources of funding of national park biodiversity management activities in Bangladesh, where citizens’ contribution in the form of volunteer tree planting are also snowballing. In the way, the research is fully embedded in permanent structure of the target groups through community level to bureaucracy levels, who are involved in planning, decision-making and implementation of activities operational, technical, institutional and management capacities are being developed at all levels.As a result, target groups, at all levels show full ownership of research activities including ecological, economic, social and political factors, as shown in Figure 13, indicating today–tomorrow with internal and external services and benefits for potential sustainable biodiversity conservation towards national parks. Regular reporting to CBD, which enhance the high-level profile and supports, facilitates the active engagement of national contact points of Bangladesh and Secretariat of CBD. The high-level meetings / roundtables have also agreed to advance the national park biodiversity conservation systems and to highlight its use at the head-of-state/ government level.

| Figure 13. Potential Sustainability for Biodiversity Conservation |

5.5. Improvement to the Wildlife Conservation and Security Act 2012

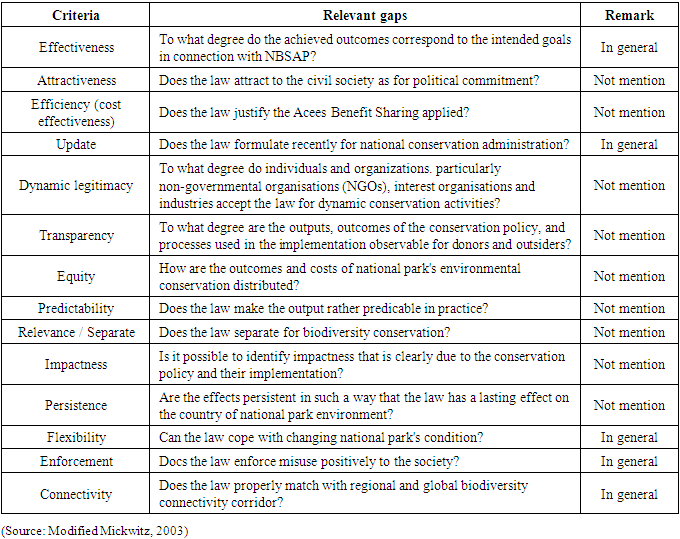

- The Environmental Conservation Policy Instruments have become outdated on the wildlife habitat losses and in many cases, inappropriate (IPAC, 2012) on the priority of political commitment and global agreements. However, the Wildlife Conservation and Security (WCS) Act 2012 is the latest as well as pioneer revision of conservation law in Bangladesh. From the result, it was shown that the law has a comparative advantage against other conservation laws in Bangladesh and South-south-east Asian region. However, several improvements could be included in the WCS to make it effective implemented and enforced. These are mentioned as below:(a) The WCS Act and Forest Act are the provisions for nature conservation for the present and future citizens in Bangladesh, which allow the local and indigenous communities to freely involvement for the development with specific part of forest areas. It might be better to integrate both protected areas and reserved forests into national park on the priority of Aichi Biodiversity Targets 2020. In addition, the Act should explicitly describe the functions on national park, wildlife sanctuary, botanical garden, eco-park, safari park, special conservation and community areas. This could augment the protection of biodiversity by obligatory the loyalty of forestry organizations to accomplish the national park according to the functions with access benefit sharing provided by this Act. (b) The WCS Act 2012 has no Section for the protection of undergrowth species, which is a part of biodiversity of national park. These species contribute the enhancement of soil surface and vegetation structure with nutrient recycles. This could enhance the protection of national park biodiversity according to the requirements of Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).(c) The WCS Act 2012 has no a single section for the development of national park biodiversity database on the priority of biodiversity clearing house mechanism (BCHM) of CBD. The BCHM is the system of exchange information among of all state parties according to the constitutional requirements of CBD. Till to date, Bangladesh has not effective national park biodiversity database in connection with CBD. But the Government of Bangladesh has taken initiatives for it, meanwhile she declared as “digital Bangladesh” with its vision 2020. The BCHM could enhance the biodiversity informatics of national park resources to share information of each state party as well as sending nation biodiversity reports to CBD. (d) The WCS Act 2012 included the collaborative management system for protection of national park resources. It is good Section to involve the various stakeholders. But the Section could not mention specifically some stakeholders, such as: indigenous community leader, sawmill licensee, brick manufacturer, tea estate manager, and academic researcher, manager of green banking performed activities, rain water harvester, forest nursery manager, betel-leaf cultivator, home gardener, social forester, pesticide entrepreneur and environmental educationists. It might be better including them that could be enhancing the protection of national park biodiversity. For example, the Iban have been settled in and around the Batang Ai National Park at Sarawak in Malaysia. They have historically played a major role in orang utan conservation as they have a strict taboo against harming these animals; some group believe these animals are inhabited by the soul of departed ancestors (SF, 2016). (e) The advancement towards national park biodiversity management and multiple use of park resources shall take leading indication. However, these phenomena are augmenting attentiveness and prerequisite for the national park to be achieved sustainably, as it is dynamic means of natural resources in preventing environmental catastrophe and climate change. Amid this, it is surprising that the WCS 2012 has not include a single Section or Article on these issues, excluding a nebulous provision for formation of rules on the obligation for national park management and restoration of NBSAP as well as means to take advantage of ecosystem services. Hence, it is imperative for the provision on sustainable management, multiple uses of parks to be incorporated in this WCS Act. At the same time, the proposed improvement Act should recognize the importance of public participation and education in order to increase the effective enforcement of this Act, and inculcate the responsibilities in protection of national park resources in the country. In addition, the improving legislation intends to harmonise national park biodiversity conservation laws and policies. The objectives of improving WCS Act 2012 are prioritised six main aspects, such as:(i) Conserving biodiversity – Constitutional Rights (Article 18A). (ii) Enhancing productivity and functionality of the National Park Ecosystem (iii) Safeguarding variety, i.e. beauty and recreational value of National Park. (iv) Access Benefit and Sharing (ABS) in connection with CBD’s objectives. (v) Application of digital conservation technology on the priority of BCHM, e.g. National Park database, Monitoring database, Tourist database. (vi) Scientific Policy for Removal of Invasive Alien Species in connection with ABT. From Table 12, the study observed that only 36% ‘In general’ and 64% ‘Not mention’. Therefore, the existing law needs to improve. Moreover, from the desktop observation, the existing conservation related laws and policies contain some evaluation gaps (Mickwitz, 2003) for sustainable biodiversity conservation in connection with Sustainable Development Goals 2030. In addition, Bangladesh requires a comprehensive biodiversity law in response to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which embraces the three objectives of the CBD, (a) conservation of biodiversity, (b) sustainable use of resources, and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits from the utilization of genetic resources to satisfy the needs of present and upcoming generations on the priority of intra-inter-generational equity.

|

6. Conclusions

- The study had assessed two instruments of four types of conservational instruments of Convention on Biological Diversity. These are legal and in-situ instruments for Bangladesh with Lawachara National Park (LNP) – as a study site. Based on these instruments, LNP is not well managed on the priority of national park management effectiveness and political commitment for biodiversity conservation. However, this study has attempted to develop a complete scenario of the causes of less management on LNP Biodiversity Conservation in Bangladesh. The findings of this study clearly indicate that traditional forest policy, illegal logging, wildlife poaching, NTFPs collection, parkland encroachment, excessive invasive alien species and no national park database in connection with biodiversity clearing house mechanisms are important sources for loss of biodiversity at LNP. However, the predisposing conditions of this LNP also have the influential effects on local corruption and politics along with weak government policies, institutional weakening to the losses of biodiversity and this would be implemented by sustainable alternative policy approaches, which provide immediate to poor households. At the same time, National Park Biodiversity Management will need to be modernized through a long term effective national biodiversity strategy and action plan including all dynamic administration, pertinent stakeholders and update National Park Database for biodiversity clearing house mechanism in this process. The results of this study support the adoption of environmental policy instruments that create National Park Biodiversity Protection in Bangladesh. The analysis observes the Aichi Biodiversity Targets 2020 based on National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan. The analysis also supports using compositional targets based on natural disturbance and settlement simulations at the community level with the involvement of various stakeholders. Spatially explicit, quantitative National Park biodiversity conservation model developed for a focal set of plant and animal species describe the target levels and range of variability in national park conditions required, as a minimum to support the occupied supplement of Lawachara National Park Biodiversity. The simulated range of in-situ instruments helps define the legal and informational instruments that should be expected for both environmental conservation instruments and associated alternative policy options. The approach is of strategically modelling long-term patterns, but using realistic operational constraints, adds both validity and complexity to model interpretation. Overall, Appropriate policy integration and effective management are absent till date for enhancing biodiversity conservation at Lawachara National Park. Rainwater harvesting reduces water scarcity and removal illegal hunting during wildlife migrates outside at dry and winter seasons. Overall, the research stated the dynamic legal instruments at national parks with requirements policy improvement for sustainable nature conservation to the effective policy makers and relevant bodies with interconnected training and socio-technical arena, which contributes to park management at national and global perspectives.

7. Conflicts of Interests

- The authors declare no potential conflict of interest in this research. The funders had no role in the design of the research, in data collection, analyses or final interpretation of data, in the writings of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the findings.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML