-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2018; 8(6): 197-203

doi:10.5923/j.ijaf.20180806.01

Agrarian Conflicts in Islands Areas (Case Study in Maluku Islands, Indonesia)

August E. Pattiselanno, Junianita F. Sopamena

Department of Agribusiness, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Pattimura, Ambon, Maluku, Indonesia

Correspondence to: August E. Pattiselanno, Department of Agribusiness, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Pattimura, Ambon, Maluku, Indonesia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

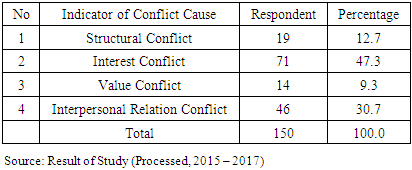

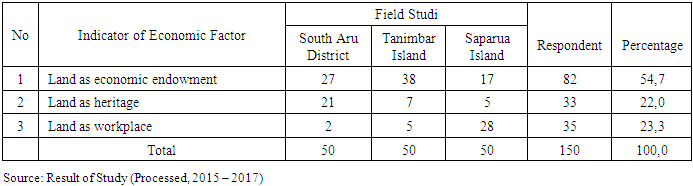

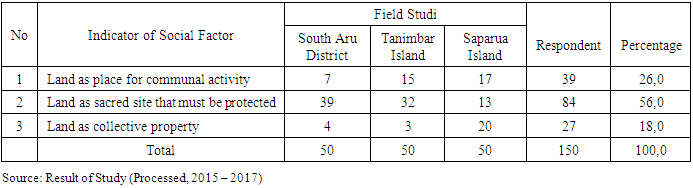

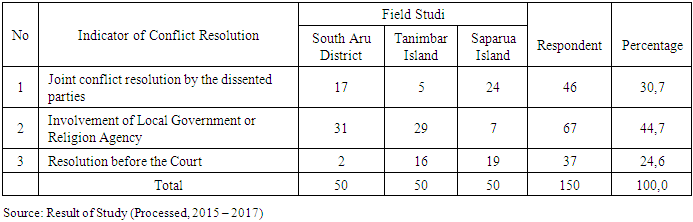

This study was aimed to analyze the source and resolution of agrarian conflicts in small islands. Focus was given on three small islands, namely Tanimbar Islands, Aru Islands, and Saparua Island. Sample contained with 150 individuals who are selected purposively and among them, there are 50 individuals drawn from each location. Method of study was qualitative approach. Result indicated that the history of agrarian conflicts in small islands was varying. Agrarian conflicts in the observed locations have occured long ago since Dutch colonialism, including conflicts among villages. Recent conflicts are mostly between business firm and people. The source of agrarian conflicts in small islands is dominated by interest conflict with 47.3 percents, followed by interpersonal relation conflict with 30.7 percents, structural conflict with 12.7 percents, and value conflict with 9.3 percents. The results of the chi-square analysis show that the Chi-square value is calculated (56,543) greater than the Chi-square table, so that economic factors are closely related to the occurrence of conflict in the three research locations. The results of the chi-square analysis showed that the Chi-square value was calculated (37.43) greater than the Chi-square table, so that social factors were closely related to the occurrence of conflict in the three study locations. There are few resolution paths for agrarian conflict in small islands, such as involving Local Government and Religion Agency, joint resolution by the dissented parties, and resolution before the Court. The results of the chi-square analysis show that the calculated Chi-square value (41.1) is greater than the Chi-square Table, so that the chosen conflict resolution is related to conflict resolution in the three research locations.

Keywords: Agrarian conflicts, Conflict source, Conflict resolution, Social-economical factors, and islands areas

Cite this paper: August E. Pattiselanno, Junianita F. Sopamena, Agrarian Conflicts in Islands Areas (Case Study in Maluku Islands, Indonesia), International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 8 No. 6, 2018, pp. 197-203. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20180806.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

- In any nations, conflict is always inevitable in natural resource management, including that in Indonesia. Reason behind this conflict is too obvious, that is, too many parties have interest on nature, and each party always has different necessity and goal. The need for natural resource has been increasing along with the development of the age. The increase of living standard, the decline of mortality rate, and the dramatic advancement of infrastructures, however, have created not only huge social gap among societies but also wide discrepancy between rich and poor, urban and village, West side and East side, and also between man and woman.Indonesia is an agrarian country but agrarian conflicts are easily found across the regions. Many people compete each other to acquire productive land because such land is a factor that can support livelihood and welfare. Agrarian conflicts can happen not only among individuals or between individual and group, but also among the groups when each of them claims the property right on disputed land. Agrarian conflicts can grow into a long dispute that may provoke physical clash among dissented parties, which potentially weakens national political stability. Pursuant to the report given by the Consortium of Agrarian Revitalization ([12] KPA, 2017), agrarian conflicts in Indonesia on Period 2010-2014 have shown the increasing trend. In 2010, there were at least 106 agrarian conflicts in Indonesia regions, but this number ascended four folds in 2014 into 472 agrarian conflicts in Indonesia. In 2015, the number went down to 252 agrarian conflicts, but it was followed by drastic ascension in 2016 to 450 agrarian conflicts. The coverage of disputed land in 2016 was around 1,265,027 hectares and this dispute involved 86,745 households. Moreover, during 2017, there were 659 agrarian conflicts in Indonesia. It leaped upward for 50 percents compared to previous year. The disputed land was counted around 520,491 hectares. With respect to upsurge trend of agrarian conflicts, it can be said that agrarian conflicts in Indonesia have reached critical point because there are two conflicts at least occuring in daily basis. As said by [19] Setiarsih (2012), agrarian conflicts may occur not only among individuals, or between individual and group, but also among the groups because each group can endeavor to seize the property right on the disputed land. Also shown in a review by [1] Anton Lucas and Carol Warren (2013), the revocation of the 1960 Agrarian Principal Act has put the government into difficulty to resolve agrarian conflicts. Maluku is a province in Indonesia that still remains susceptible to various conflicts, including conflict among tribes, conflict among religions, and also conflict concerning land posession. All these conflicts only lead to a social cleavage that surely brings bad impact on society. Agrarian conflicts in Maluku are mostly interest conflicts involving people who consider their land as heritage against investors who are supported by Local Government. These conflicts are too obvious to be denied, and in many cases, it involves death victims, especially conflict to seize control over illegal gold mining lands. The escalation of conflicts is always rapid and extensive, which indicates that the nation has been incapable to resolve agrarian issues.

1.2. Problem and Objective

- The understanding of problem background has given a temporary deduction that the study on agrarian conflicts in small islands is rarely conducted. Therefore, the current study shall be very important initiative. The formulated problem is: “How is the description of the source and resolution of agrarian conflicts in small islands?” The objective of this study is therefore to analyze the source and resolution of agrarian conflicts in small islands. It is expected that result of this study would be reference material for other studies about agrarian conflicts.

2. Method

- The study was conducted for six months and the timing was distributed evenly on each location. Two months were spent on Aru Islands (at Marfen-fen, Popjetur, Ngaiguli, and Kalar-kalar Villages in South Aru District). The other two months were used on Tanimbar Islands (at Arma and Watmuri Villages in Nirunmas District). The final two months were applied on Saparua Island (at Ihamahu and Sirisori Sarani Villages). Sample was determined purposively, and it comprised with community personage (10 persons), religion personage (10 persons), custom personage (10 persons), village civil servant (10 persons), and finally, education and youth personage (10 persons). Total sample on each location was 50 persons, and therefore, the sample of study became 150 persons. Data were collected through deep interview and observation. Deep interview was conducted directly with respondents using semi-structured questionnaires as the instrument to collect information. Data type included primary and secondary data. Primary data were obtained directly from the field using questionnaires that must be answered by respondents during deep interview and field observation. Secondary data were acquired from village office or other agencies relevant to this study. Data analysis was done qualitatively ([14] Moleong, 1989; [13] Miles and Huberman, 1992; [5] Denzin and Lincoln, 1994; [4] Debus and Noveli, 1996; [2] Babbie, 2004).

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Source of Conflict in Islands Areas

- Conflict on natural resource is mostly coming from two sources. One is individual dispute concerning small issues, and other is overt conflict, which may become obvious when the dispute cannot be settled. Both can also combine into one grand source of conflict, which makes conflict becoming more complex. Therefore, the center of critical situation, or also called as the principal problem or source of conflict, must be defined properly, and such definition can be obtained by observing and understanding the interest of the dissented parties. Result of observation on three locations of study has found few sources of conflict on natural resource (also indicated in Table 1). These are explained as follows:1. Structural Conflict. This conflict happens due to the partiality on both access and control of natural resource. The party with power and formal discretion to make general policy always has greater chance to have discriminant access and control of the resource. Moreover, geography and historical factors are often used as reasons behind the centralization of power and decision-making in favor of one side over the others. (The cases of conflict in Aru Islands).2. Interest Conflict. This conflict develops when incompatible interests are competing for giving influence on certain issue, which in this study, it is natural resource management. One side may believe that the other side, which may be less powerful, must sacrifice their interest to allow the powerful side to satisfy their interest. Interest-based conflict always emerges during the dispute concerning natural resource management. (The cases of conflict between Arma and Watmuri Villages in Tanimbar Islands, between people and firm in Aru Islands, and among villagers at Ihamahu and Sirisori Sarani Villages).3. Value Conflict. This conflict is caused by the disharmony of one credence system against anothers. Value is a credence system used by individual to give a meaning to the life. Value can explain which thing is good or bad, right or wrong, and just or unjust. Value dissidence shall not provoke conflict, but when a value system is compelled by an individual to other, conflict arises. (The cases of conflict between people and firm in Aru Islands, because there is value dissidence concerning land as agrarian resource, where people perceive land as hunting spot that allows them to conserve their socio-cultural value, while firm considers land as having economic value for development interest). 4. Interpersonal Relation Conflict. Every human has such conflict. Reason behind this conflict is varying, such as strong negative emotions, mis-perception, stereotype, mis-communication, or repeated negative postures. The cause of this conflict may be trivial, but the consequence greatly impacts on humanity because it potentially victimizes people and their properties. (The cases of conflict between Arma and Watmuri Villages in Tanimbar Islands, and between Ihamahu and Sirisori peoples).

|

3.2. Factors Causing Conflict in Islands Areas

- Conflict causal factors are enormous. According to [24] Soerjono Soekanto (2006), there are four factors with the greatest effect on conflict emergence, namely individual differences, cultural differences, interest differences, and social changes. The current study has conducted field review and found that economic and social factors are the strongest factors that cause agrarian conflicts in three locations of the study. These two factors would be explained as follows. Economic FactorWatmuri Village has experienced agrarian conflicts for many years. These conflicts have put Watmuri people to suffer from losing their livelihood, either as farmer or laborer. Social gap and unfulfilled economic necessity are only worsening the problem, especially for those who are unemployed. In general, people want quick resolution to these conflicts. Years of conflict over their right over land have forced them into exhaustion. Meanwhile, people in Aru Islands perceive forest as their economic endowment. Activities that potentially degrade the forest would disturb their economic livelihood. Most of them work as farmer. Although some others work as fisher, they do not abandon their farmland and still work as farmer during famine season when sea wave is too unfriendly for fishing. People in Ihamahu and Sirisori Villages also face agrarian conflicts. Both of them live on the coast. They work as farmer and fisher depending on season. Land still becomes important resource for fulfilling life necessities. They perceive land as source of livelihood. Further description would be given in the following Table 2. The results of the chi-square analysis show that the Chi-square value is calculated (56,543) greater than the Chi-square table, so that economic factors are closely related to the occurrence of conflict in the three research locations.

|

|

3.3. Resolutions of Agrarian Conflicts in Islands Areas

- Agrarian conflicts in small islands can only be resolved by acknowledging land ownership status. These conflicts are quite evident among society members. Community-based perception has put some difficulties to the dissented parties in exercising resolution. Also, the legal status of disputed land is always hardly certain because land does not have certification of ownership or any evidences that indicate the real owner. If the conflicts encounter stalemate, then the following conflict resolutions (Table 4) can be reserved:1. The dissented parties must endeavor to produce joint conflict resolution and also refrain themselves from breaking the collective agreement. 2. Third-hand intervention can be taken into account, such as from Local Government or Religion Agency, which may help the dissented parties to develop reconciliation or mutual agreement that benefits both of them. 3. If the reconciliation mediated through Local Government or Religion Agency shall be failed, the case of conflict can be brought before the Court.

|

4. Closing

4.1. Conclusions

- 1. The source of agrarian conflicts in small islands is made of four indicators, namely structural conflict, interest conflict, value conflict, and interpersonal relation conflict. As shown by data from three locations of study, the most dominant cause of agrarian conflicts is interest conflict, followed by interpersonal relation conflict, structural conflict, and value conflict. Almost all agrarian conflicts are always derived from different interests of the dissented parties. Main interest, that is, accessibility to the land as agrarian resource, is often hampered by the presence of others on the land or other’s claim over the land. Therefore, the cause of agrarian conflicts in small islands can be narrowed into two factors, namely economic factor and social factor. 2. Economic factor as the cause of agrarian conflicts comprises with three indicators, respectively: land as economic endowment, land as workplace, and land as heritage. All these indicators are interrelated. Land as workplace will give income to the owner. Land as heritage can be cultivated as workplace, especially as farmland, which then delivers outcome to the owner. Principally, land functions as economic endowment to societies. 3. Social factor as the cause of agrarian conflicts consists of three indicators, respectively: land as sacred site, land as place for communal activity, and land as collective property. These three indicators are also interrelated. Land as collective property may be used as place for communal activity. The engagement of people onto this land may then develop perception that land is sacred site and thus, must be protected. 4. People tend to use third party assistance during conflict resolution. This third party can be Local Government or Religion Agency, which then mediate the discussion between the dissented parties. However, if the discussion for conflict resolution is getting stuck, then conflict case shall be brought into the Court for final resolution.

4.2. Suggestion

- Recalling to the fact that land is agrarian resources for societies in small islands, then local government in those small islands shall be prepared itself with various problem-solving alternatives for any cases concerning land ownership. This preparation also helps the government to fulfill the society’s demand for certain land. The government must also build education capacity among the societies to develop active participation in conflict resolution process. Moreover, a reconciliation-based conflic resolution can only be attained through a collaboration between Local Government and Religion Agency. If reconciliation process shall fail, the conflict case must be submitted to the Court in order to receive absolute settlement with strong legal reasoning. The final verdict on agrarian conflicts is always on the compliance with the existing laws, which people expect that it deserves the willingly obedience of the dissented parties.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The completion of this study cannot belittle the contribution of our students, notably Martafina Lokarleky, Harry Fadly Umamit, and Adrana Batlajery. Their assistance in collecting the data for this study is always greatly appreciated.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML