-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2017; 7(6): 134-139

doi:10.5923/j.ijaf.20170706.03

Performance of Four Different Rice Cultivars under Drought Stress in the North-Western Part of Bangladesh

Montasir Ahmed1, Md. Ehsanul Haq2, Md. Monir Hossain3, Md. Shefat-al-Maruf4, Mir Mehedi Hasan5

1Plant Pathology Division, Bangladesh Rice Research Institute, Gazipur, Bangladesh

2Department of Genetics and Plant Breeding, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3Institute of Seed Technology, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

4Department of Agronomy, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

5Adaptive Research Division, Bangladesh Rice Research Institute, Gazipur, Bangladesh

Correspondence to: Montasir Ahmed, Plant Pathology Division, Bangladesh Rice Research Institute, Gazipur, Bangladesh.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Drought stress has become a regular phenomenon for the rice farmers during late aman season (June to October) in the northwestern part of Bangladesh. The experiment was carried out at the regional station, Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI), Rajshahi, Bangladesh during Transplanted aman (T. aman) season in 2014. The experiment comprised of four different rice cultivars viz. BRRI dhan39, BRRI dhan56, BRRI dhan57 and Ganja. The experiment was laid under two different field conditions i.e. drought stress and control condition. Days required for 50% flowering, total growth duration, plant height, number of panicle m-2, number of tiller m-2 and grain yield was recorded during the experiment. The yield reduction in stress condition, control and stress tolerance index (STI) were calculated. Among the four varieties, the results revealed that Ganja and BRRI dhan56 performed better during the drought stress and the control condition. Ganja and BRRI dhan56 gave the highest value for grain yield in both conditions. Yield reduction percentage was lower in both Ganja and BRRI dhan56. STI was also found to be higher in these two varieties, which indicate the ability to give stable yield performance under stress condition. Ganja and BRRI dhan56 cultivars can be cultivated in the drought-prone area with better yield.

Keywords: Rice, Oryza sativa L., T. aman, STI, Drought stress

Cite this paper: Montasir Ahmed, Md. Ehsanul Haq, Md. Monir Hossain, Md. Shefat-al-Maruf, Mir Mehedi Hasan, Performance of Four Different Rice Cultivars under Drought Stress in the North-Western Part of Bangladesh, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 7 No. 6, 2017, pp. 134-139. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20170706.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- About half of the world’s population consumes rice as a staple food. However, Asia solely consumes more than 90% of this rice [1]. Bangladesh is the fourth-largest rice grower in the world [2]. About 150 million people of Bangladesh consumed rice as a principal food. About 34.7 million tons of rice is produced in Bangladesh per annum and about 75% of the cultivable land is used for rice production [3]. The country’s rice production has increase over the years [2]. However, 20.7% production gap of rice is still available in Bangladesh [4]. In recent years, drought stress has become a big challenge for the rice farmers of the northwestern region of the country. Every year about 0.34 million ha of land are affected by severe drought in north-western Bangladesh [5]. Therefore, the drought stress has turned to a threat to achieving country’s self-sufficiency in rice production. Irrigation is the only common practice for the farmers to deal with the drought stress during late monsoon. In rainfed condition, rice production can undergo dry spell at almost any period during the growth duration leading to drought stress. However, water stress during reproductive stage leads to spikelet infertility of rice [6]. The drought has a high impact on in growth duration, yield, membrane integrity, pigment content, osmotic adjustment, water relation and photosynthetic activities [7]. Water stress also impairs normal growth, disturbs water relations, and reduces water use efficiency in plants. Due to drought, the rate of photosynthesis is reduced mainly by stomatal closure, membrane damage, and disturbed activity of various enzymes, especially those involved in ATP synthesis [8]. Drought tolerant rice varieties may act as an alternative to reduce the pressure for excess use of groundwater. Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI) has developed some drought tolerant rice varieties in recent years. Some local varieties of Bangladesh have some drought tolerant characters. The present study was taken to check the yield performance of four different rice cultivars under drought condition, to make a yield comparison between drought stress and control condition, and to find the suitable cultivars for production under drought stress condition.

2. Materials and Methods

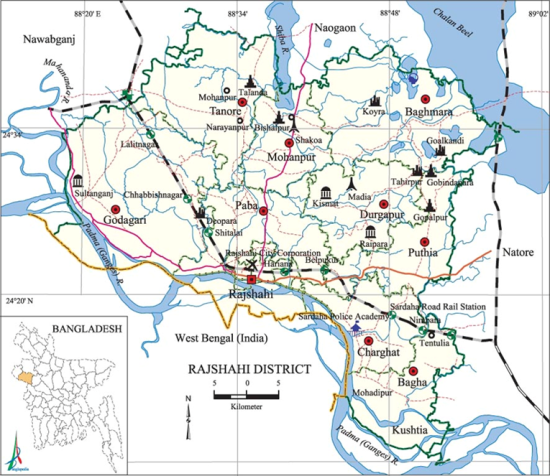

- The experiment was conducted at the regional station, Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI), Rajshahi in Bangladesh during Transplanted aman (T. aman) season in 2014 (Figure 1). Experimental sites were under “High Ganges River Floodplain” (AEZ 11) agro-ecological zone of Bangladesh, which is predominantly highland to medium highland. General soil type of this area is calcareous brown floodplain soils and the soil fertility level is low with low organic matter content [9]. Four different rice cultivars viz. BRRI dhan39, BRRI dhan56, BRRI dhan57 and Ganja were used as study materials. Among the cultivars, BRRI dhan39 was a short duration rainfed lowland rice variety; BRRI dhan56 and BRRI dhan57 were short duration drought-tolerant rice varieties. These three varieties were developed and were released by Bangladesh Rice Research Institute [10]. Ganja was short duration local variety cultivated in the northwestern part of Bangladesh.

| Figure 1. Map of Rajshahi District, Bangladesh (source: Banglapedia) |

2.1. Weather Condition

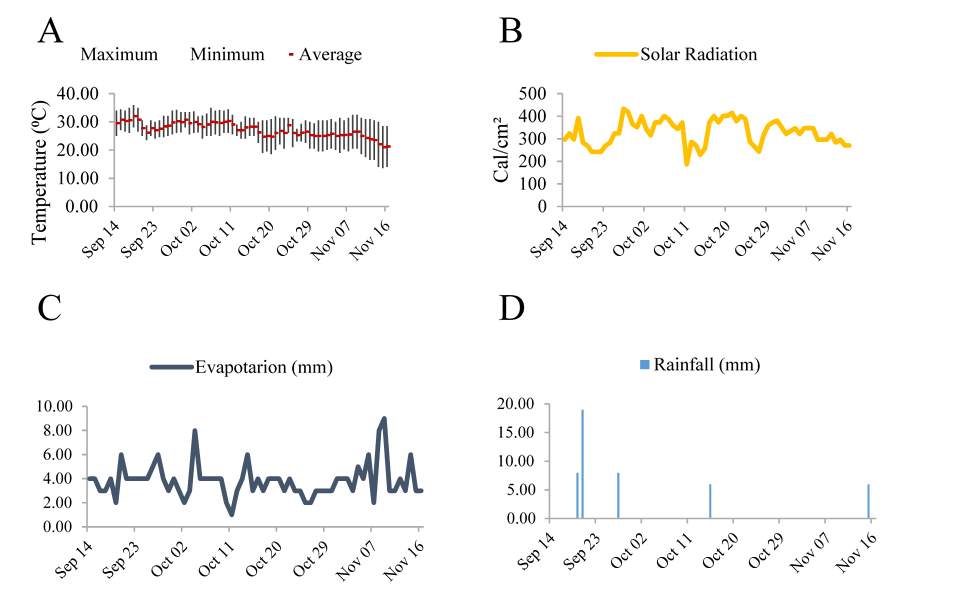

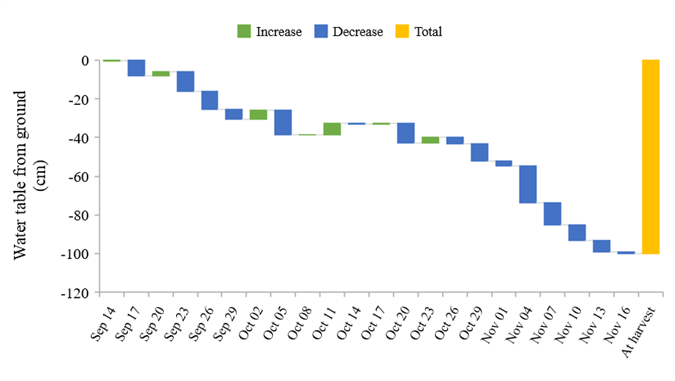

- During the experimental period, the weather was suitable for drought condition. From September 14, 2014 to November 16, 2014, average temperature, solar radiation, and evaporation was at a range of 21°C to 32°C, 186.16 Cal cm-2 to 433.13 Cal cm-2 and 1 mm to 9 mm respectively (Figure 2). In addition, rainfall was little, just 5 times during experimental period (Figure 2). Because of the weather condition and sieging of irrigation, drought-stressed plots got on moderate to severe drought from panicle initiation to maturity. Groundwater table gradually decreased and the water table was reached below 40 cm at 35 days after transplanting (Figure 3). Where the average depth of rice root zone is 30 cm to 40 cm.

| Figure 2. Weather condition of BRRI Rajshahi, Bangladesh during the experimental period. (A= maximum, minimum and average temperature, B= solar radiation, C= evaporation, D= rainfall) |

| Figure 3. Decreasing pattern of the water table from the ground of drought stress condition during the experimental period |

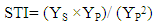

2.2. Stress Tolerance Index (STI)

- Stress tolerance index (STI) was calculated by following formula [11]:

| (1) |

= yield mean in non-stress (control) conditions.

= yield mean in non-stress (control) conditions.2.3. Data Analysis

- Data generated were subjected to Statistical Tool for Agricultural Research (STAR) and combined analysis of variance (ANOVA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Days Required to Flowering and Growth Duration

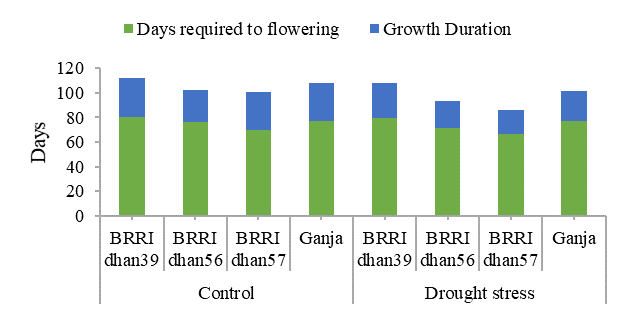

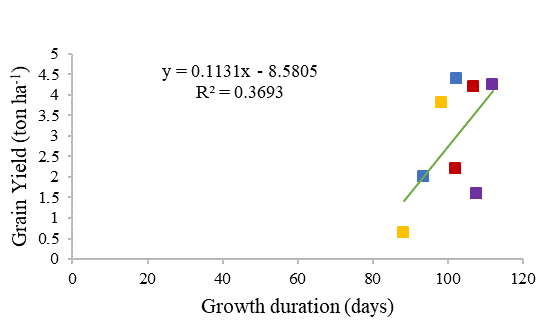

- Days required to flowering and growth duration were statistically significant among the cultivars as well as between the conditions (Figure 4). Among the cultivar, BRRI dhan57 required least days to completed 50% flowering in control condition (69.33 days) as well as in drought stress condition (66.67 days). Days required to flowering was significantly different among the cultivar in addition to control and drought stress condition. BRRI dhan39 took highest days among the cultivar to reach 50% flowering both in control condition (80.00 days) and drought stress condition (79.67 days). Between the control and drought stress condition, BRRI dhan56 and BRRI dhan57 showed a significant variation in flowering dates. Other two cultivar showed statistically similar flowering dates among the two condition, but all four cultivars took less duration on drought stress condition than the control condition. This result indicates that stress condition enhances early flowering of the rice plant.

| Figure 5. Effect of growth duration on the yield of the different cultivars |

3.2. Plant Height

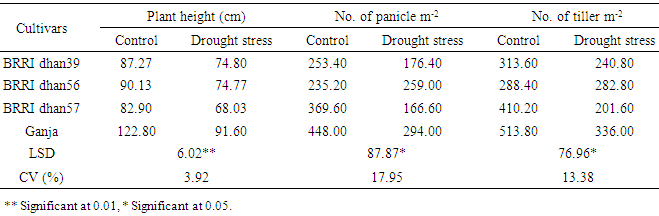

- Plant height was significantly different within the cultivar in both control and drought stress condition (Table 1). Among the cultivar, Ganja achieved highest plant height (122.80 cm) in control condition and BRRI dhan57 got lowest plant height (68.03 cm) in drought stress condition. It was observed that individual variety had significant different plant height between control and drought stress condition (Table 1). Each variety achieved lower height in drought stress condition compared to control condition. This result indicates that water stress situation has a high impact on plant growth and results in the reduction of plant height.Water stress reduces the cell size and cell division, which may affect the plant height in drought condition. Ahmadikhah & Marufinia [13] found a significant reduction of plant height at water deficient condition in their research. Sarvestani et al. [14], Ashfaq et al. [15] and Sokoto & Muhammad [16] also observed lower plant height on water stress condition.

3.3. Number of Panicles m-2

- Significant different plant height was reordered among the cultivar in both control and drought stress condition (Table 1). Highest no. of panicle m-2 was recorded from Ganja in both control (448.00) and drought stress condition (294.00). Lowest no. of panicle m-2 was observed from BRRI dhan56 (235.20) in control condition and BRRI dhan57 (166.60) in drought stress condition. No. of panicle m-2 of BRRI dhan39 and BRRI dhan56 was statistically similar between control and drought stress plot but BRRI dhan57 and Ganja reduced the significant number of panicle m-2 (Table 1) in drought stress condition.

|

3.4. Number of Tillers m-2

- Statistically different tiller number among the cultivar was recorded in control condition as well as drought stress condition (Table 1). Ganja gave the highest no. of tiller (513.80) in control condition and BRRI dhan57 gave the lowest (201.60). In between control and drought stressed condition, BRRI dhan39 and BRRI dhan56 produced statistically similar tiller number and BRRI dhan57 and Ganja produced significantly lower tiller in drought stress than control condition (Table 1). Ashfaq et al. [15] and Bunnag & Pongthai [17] also found less number of tillers under drought stress.

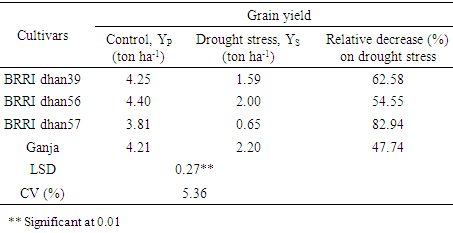

3.5. Grain Yield

- Grain yield was significantly different both among the cultivars and between the conditions (Table 2). Among the cultivars, highest grain yield was produced by BRRI dhan56 (4.40 ton ha-1) at control condition and by Ganja (2.20 ton ha-1) at drought stress condition. BRRI dhan57 was the lowest yielder in both control (3.81 ton ha-1) and drought stress (0.65 ton ha-1) condition. BRRI dhan56 and Ganja both were statistically similar yielder in control as well as in drought stress condition. Pirdashti et al. [18] and Ahadiyat et al. [19] reported that grain yield of rice severely reduces under drought stress. Highest yield reduction was observed under drought stress in BRRI dhan57 (82.94%) followed by BRRI dhan39 (62.58%) and BRRI dhan56 (54.55%), while less reduction was noted in Ganja (47.74%) (Table 2). Liu et al. [20] also reported that water stress condition reduces grain yield. Due to some physiological condition, induced by drought stress, may reduce grain yield. Reduction of CO2 assimilation rates, stomatal conductance, photosynthetic pigments and starch synthesis enzymes in drought stress leads to reduce plant productivity [21].

|

3.6. Stress Tolerance Index (STI)

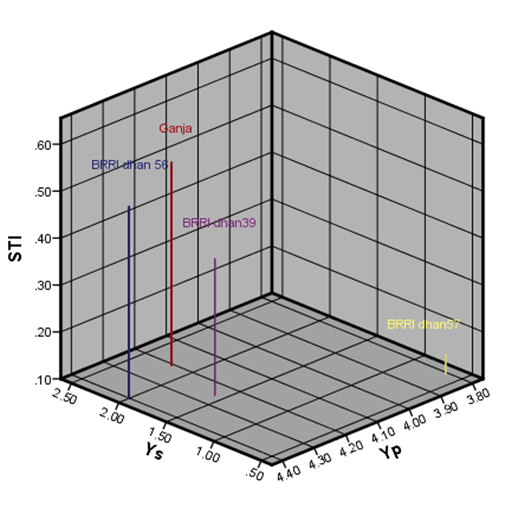

- A three-dimensional plot [11] of YP, YS and STI (Figure 6) was used to separate the group A generations (with high YP, YS and STI) from the group B generations (with high YP), group C generations (with high YS) and group D generations (with low YS and YP).

| Figure 6. Three-dimensional plot of STI, YP and YS for the four rice cultivars |

4. Conclusions

- It is concluded from the present study that Ganja and BRRI dhan56 both perform well in drought stress among the four varieties. Ganja and BRRI dhan56 both gave the highest panicle number, tiller number, and yield among the tested varieties. Lower yield reduction in drought stress and Higher STI value was also observed in Ganja and BRRI dhan56. Finally, it can be recommended that Ganja and BRRI dhan56 both can be cultivated in drought prone area to get a better yield.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML