-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2017; 7(4): 95-101

doi:10.5923/j.ijaf.20170704.03

A Thinkable Model for Enhancing the Commercialising Potential of Small Scale Aspiring Agri-Entrepreneurs in Zululand District Municipality of Kwazulu Natal Province, South Africa

Gugulethu G. Xaba, Kudzai Mandizvidza

Department of Research and Development, Adamo Agric Business (Pty) Ltd, Gauteng, South Africa

Correspondence to: Kudzai Mandizvidza, Department of Research and Development, Adamo Agric Business (Pty) Ltd, Gauteng, South Africa.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Advancing the welfare of the previously disadvantaged farming communities has for more than two decades taken the centre stage in South Africa. This study attempts to unearth the skill-based challenges that South Africa’s emerging and small scale agri-entrepreneurs must overcome. A self-administered survey was undertaken to collect primary data from a randomly selected sample of emerging and small scale farmers in the Zululand District Municipality of KwaZulu Natal Province, South Africa. A logit model was employed to analyse the skills that are essential for the success of South African small scale aspiring Agri-entrepreneurs. A possible entrepreneurial model that outlines the expertise required to integrate these historically disadvantaged farming entrepreneurs into the South African mainstream economy is proposed. It is anticipated that empowering the aspiring Agri-entrepreneurs with skills in enterprise management, marketing competency, production proficiency, Information and Communication Technology, and financial management will go a long way in turning their subsistence activities into viable commercial ventures.

Keywords: Agribusiness, Emerging farmers, Entrepreneurship, Small scale farmers, South Africa

Cite this paper: Gugulethu G. Xaba, Kudzai Mandizvidza, A Thinkable Model for Enhancing the Commercialising Potential of Small Scale Aspiring Agri-Entrepreneurs in Zululand District Municipality of Kwazulu Natal Province, South Africa, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 7 No. 4, 2017, pp. 95-101. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20170704.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Post-apartheid Republic of South Africa witnessed a dualistic agricultural economy where the minority established commercial farmers coexist with a majority, under resourced and usually struggling, small scale and emerging farmers. The Government of the present day South Africa has however sought to steer itself towards bringing forth a nation that will achieve an equitable distribution of wealth for all its citizens. Over the years of democratic rule, the South African Government has promulgated a number of interventions aimed at addressing the imbalances, caused by the architects of apartheid, on the economic, social and political front. These include among others, Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE), Land Reform policies, Employment Equity (EE), the Co-operative Act of 2005, and many others. Despite of interventions by the government, the small scale farmers across South Africa still face a lot of challenges as revealed in literature (e.g., [1]; [2]; [3]; [4]; [5]).

2. Research Objective and the Significance of Study

- This study sought to uncover the skill-based challenges experienced by emerging and small scale entrepreneurs in the farming sector in South Africa. It is hypothesised that the skills that are essential for turning South African small scale farmers into successful Agri-entrepreneurs are implicit and generally ambiguous. Hence, this study aims to propose an entrepreneurial model that outlines the expertise required to integrate these historically disadvantaged farming entrepreneurs into the South African mainstream economy. It is anticipated that empowering these aspiring Agri-entrepreneurs with the necessary skills will go a long way in turning their subsistence activities into viable commercial ventures.

3. Literature Review

- According to Genis (2012) of the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, the foundation for South Africa’s large-scale commercial farming sector was laid by government policy intervention between 1910 and 1980. This was done by legislation to first segregate white and black farmers and then to facilitate orderly marketing. This was followed by instituting interventions and direct subsidies that decreased the white farmers' dependence on black labour and protected them from overseas competition [7]. White commercial farmers still received financial support and subsidies to the value of R3 912 billion during the 1980s and early 1990s. This was used primarily to purchase land, implements and livestock; for debt consolidation; to improve infrastructure; for emergency draught schemes and among other things to convert marginal land [8]. The Land Bank Act of 1912, Land Act of 1913 and 1936, the Co-operative Societies Act of 1922 and 1939, the Native Administration Act of 1927 and the Marketing Act of 1937 laid the foundation for the almost total segregation of agriculture and indeed for a comprehensive system of support measures to white farmers [6]. After South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994 followed by the deregulation of the agricultural marketing in 1996 this privileged position passed, transforming the agricultural sector into one that was open and sensitive to world market events [6]. The removal of policies along with the restructuring of the commercial farming sector produced, winners and losers, while the removal of government support produced a uniquely hostile environment for new entrants. Distorted land ownership patterns had created Centuries of dispossession. Land reform then came as one of the main focus of government policy to redress past injustices through land redistribution, land restitution and tenure reform.Land redistribution involved the state acquiring agricultural land for the purpose of handing it over to citizens who historically had no or little access to land. Land restitution on the other hand, aimed at the equitable restoration of property to communities or persons who were dispossessed of their land after the Native Land Act of 1913. Tenure reform intended to provide communal land residents, farm workers, former farm workers, sharecroppers, as well as labour tenants with secure occupancy on the land they are domiciled. The 21st century presents an economy that is changing and developing at an increasing rate and farm-based enterprises must adapt to the vagaries of the market, changing consumer habits, enhanced environmental regulations, new requirements for product quality, supply chain management, food safety and sustainability [9]. Farmers need to be innovative with alternative agricultural methods, for example, organic farming, landscape conservation, rural tourism, care farming and novelty in business processes and distribution such as introducing tracking and tracing systems, value-added logistics and certification. The described developments mark a shift, in [10]’s terms, from a strong, highly regulated situation towards a weak situation in which entrepreneurial competence is needed as a way to confront these new challenges ([11]; [10]). In the globalised economy, agriculture has become a commercial activity and agribusiness remains an integral part of life for developing countries like South Africa. Therefore, technological up-grade of agriculture-based enterprises has become imperative [12]. In South Africa, the Department of Land Reform and Rural Development has made it a priority to recapitalise as well as provide development support to land reform beneficiaries in rural communities to improve their capacity for economic agriculture that is sustainable. The most important feature of farming is entrepreneurship and this will be increasingly sustained for ages [13]. As which factors account for the success of entrepreneurial activities among previously disadvantaged farmers in South Africa is still being debated. In most of the developing countries, including South Africa, the majority of the rural farmers have small landholdings, limited resources and excess labour. One of the biggest challenges facing South Africa is also the development and improvement of its knowledge and skills base, particularly among previously disadvantaged and marginalised sectors of the population [14]. Other challenges, as indicated in literature include inaccessibility of finance, inadequate support systems, information asymmetry and the inaccessibility of stable markets.According to research carried out by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) in [15] a low level of overall education and training is still the biggest challenge facing South Africa. As such, a critical performance area must be to improve the overall level of education and training whilst promoting the notion of entrepreneurship [16]. The development of agri-entrepreneurship requires special skills such as the knowledge of agriculture and the global agriculture markets, among others. Although education alone is unable to prepare agricultural entrepreneurs for success, it greatly enhances their prospect of success. The literature on entrepreneurship emphasises that people with a higher level of education have a higher propensity to be self-employed ([17]; [18]). According to [17], the need to enhance the low level of formal education for the black population is now a widely accepted goal in South African politics. This will address, among other socio-economic problems, the impact that apartheid education had on its people. Apartheid education not only damaged people’s confidence and self-esteem but also deliberately inculcated a kind of passivity and learning helplessness, which is inimical to the drive and initiative required by successful entrepreneurs [19]. The report also states that apart from vast numbers of people, particularly blacks, missing the opportunity for decent education, people’s general ability to interact with the mainstream economy was severely affected. Education during pre-1994 was authoritarian and inflexible. Critical thinking and enquiry were not encouraged and no entrepreneurial education was evident [19]. [20], as well as [21], differentiate three dimensions of skills, i.e. technical skills, business management skills and personal entrepreneurial skills. Technical skills cover aspects such as written communication, oral communication, environmental change, technological development, work organisational skills, situational leadership, interpersonal relationships, teamwork, mechanisation and geological skills. Business management skills encompass goal setting, work planning, decision-making, financial management, accountability, organisational management, supervision, negotiation skills, venture creation, business development, and marketing management. Personal or entrepreneurial skills touch on issues of and abilities in self-development, self-discipline, risk taking, innovativeness, change orientation, work persistence and leadership.

4. Data and Empirical Strategy

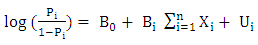

- Data was collected from a randomly selected sample of 700 respondents using a semi-structured questionnaire by means of a self-administered survey. The target population consisted of 1200 emerging small scale farmers in the Zululand District Municipality of KwaZulu Natal Province of South Africa. This is a group of the historically disadvantaged majority who are also beneficiaries the government’s Land Reform program.In analysing the skills that are required for the success of South African small scale aspiring Agri-entrepreneurs in the Zululand District Municipality, a Logit model was used by estimating Equation (1) in E-views 7.The general model can be specified as:

| (1) |

= Probability that a farmer is able to commercialise;

= Probability that a farmer is able to commercialise;  = odds ratio;

= odds ratio;  = intercept;

= intercept;  = coefficients to be estimated;

= coefficients to be estimated;  = explanatory variables to be considered;

= explanatory variables to be considered;  = Disturbance error term.

= Disturbance error term.5. Results and Discussion

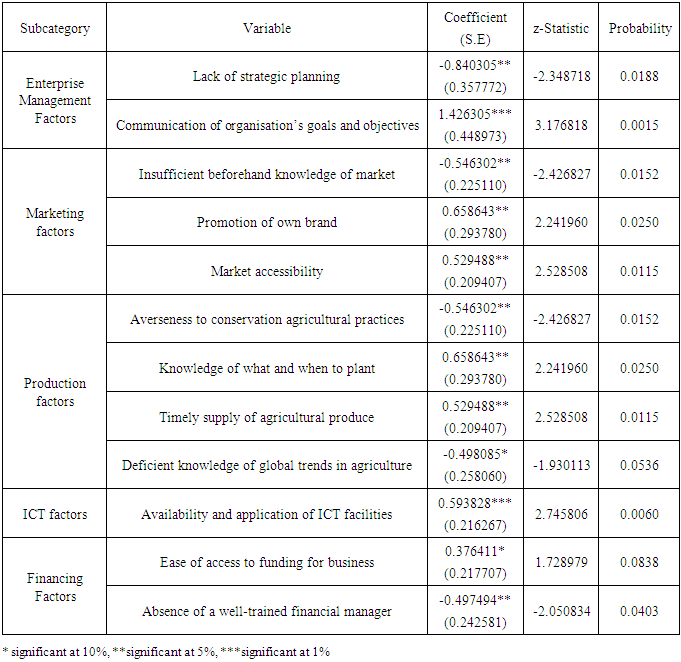

- Table 1 details the significant results of model (1) at 1%, 5% and 10% levels, where all the factors that influence the small scale farmers’ ability to commercialise are presented.

|

5.1. Enterprise Management’s Influence on the Farmer’s Ability to Commercialise

- In testing the influence of enterprise management skills on the farmers’ ability to commercialise, seven variables were considered. These include the odds ratio in favour of commercialising, strategic management as part of farming enterprise, strategic planning as part of enterprise management, definition of organisation’s vision, communication of organisation’s goals and objectives, team work, and the knowledge of competitors. According to Table 1 the absence of strategic planning as part of enterprise management was found to reduce the probability of farmers to commercialise. Possessing strategic planning skills is therefore crucial for any thriving agribusiness no matter its size. Additionally, farmers who are able to effectively and clearly communicate their organisation’s goals and objectives to their staff members have a greater likelihood to thrive in the commercial space.

5.2. The Significance of Marketing Attributes in Commercialising an Agricultural Enterprise

- In analysing marketing skills that are necessary for the success of small scale farmers, the odds ratio in favour of commercialising was regressed against six marketing variables. Marketing variables that were included in the model include availability of beforehand knowledge of the market, availability of systems to help farmers reach the target market, promotion of own brand, competitiveness of produce pricing, ease of market access and the farmers’ level of understanding of the market dynamics. Table 1 shows that lack of beforehand knowledge about the market reduces the farmers’ chances to succeed in commercial agriculture. Farmers who produce without the knowledge of where to sell their produce are less likely to thrive in commercial farming since there is a greater chance of them not meeting the specific needs and specifications of the market. Evidence from Table 1 also indicates that farmers who are able to promote their brand usually run successful commercial enterprises. In addition, the study demonstrated that market accessibility is inarguably a crucial requirement for small scale farmers’ success as entrepreneurs.

5.3. Production Skills Needed for the Success of Agricultural Enterprises

- In assessing whether there are production skills that are crucial for small scale farmers who intent to lead successful commercial businesses, a number of production related variables were considered. These include; farmers averseness to conservation agricultural practices, purchase of input far ahead of planting, knowledge of what and when to plant, customising production to meet market needs, timely supply of agricultural produce, and understanding of global trends in agricultural production. Table 1 presents a negative relationship between the farmers’ reluctance to practice conservation agriculture and their possibility of commercialising successfully. This finding reemphasizes the importance of good farming practices in maintaining the productive capacities of farmland and thus allowing for sustainable output that can meet the present and future market demands. Knowledge of what and when to plant was also found to exert a positive influence on the farmers’ likelihood to commercialise effectually. Timely supply of produce to the market also correlates positively with the probability of a farmer running a thriving agribusiness. Markets usually prefer to deal with reliable suppliers. Therefore, the more timely a farmer can convey their produce to the market the better their chances to run a thriving commercial business. Evidence in Table 1 also suggests that a lack of understanding of global trends in agriculture shrinks the possibility of farmers growing commercially. A misunderstanding of global agricultural trends means that the farmers may not be able to identify and take advantage of new opportunities in the industry. Failing to keep abreast with recent industrial trends may also imply that farmers may not timely and swiftly react to the ever-changing business environments in which they operate.

5.4. The Impact of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) in Agribusiness

- The commercialising potential of small scale farmers in relation to their command of ICT was analysed by regressing the odds ratio in favour of commercialising against six dependant variables. The six ICT related explanatory variables considered were, availability of ICT for agricultural enterprises, existence of adequate information technology skills base, access to internet, access to public and private information sources, information sharing among colleagues in a business venture and capacity building initiatives to enhance staff ICT capabilities. Table 1 shows that sufficiency and effective application of ICT on farms increases the growth chances of the small scale farmers as well as boost their potential to succeed commercially. The more the farmers utilise electronic means to store, retrieve, manipulate, transmit or receive digital data, the better is their likelihood to run successful agribusinesses. The use of computer technology in for instance, irrigation, soil sampling, communication, research and so on, is likely to improve the efficiency of agribusinesses thus boosting the farmers’ possibilities to lead successful farming businesses.

5.5. The Bearing of Financial Factors on the Likelihood of Agribusiness Success

- The influence of some financial management aspects on the small scale farmers’ commercialising potential was analysed by regressing the odds ratio in favour of commercialising against a number of financial related dependant variables. The explanatory variables considered included, adequacy of financial support for businesses, ease of access to funding, farmer’s direct involvement with the business’ finances, source of start-up capital, availability of a well-trained financial manager to a business, and use of banking facilities. Table 1 shows that the ease of access to funding poses a significantly positive impact on the small scale farmers’ likelihood to commercialise. Farmers who have access to funding are better positioned to afford good quality farming implements inputs and other resources necessary to achieve production levels and standards that meet or surpass the market’s minimum demands. It can also be interpreted from Table 1 that the absence of a well-trained financial personnel in an agri-business reduces the possibility of that respective farming unit succeeding commercially. Not having proper finance management skills base in a farm business reduces the chances of a successful commercial undertaking. Farming businesses that are headed by financially illiterate superiors often suffer from maladministration of funds which most likely dwindles their success propensity.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

- This study confirmed that some South African small scale farmers in the agribusiness sector still lack sufficient knowledge on how to run commercial agricultural enterprises effectively. The study found that some farmers are deficient in entrepreneurial management skills regardless of their importance towards the success of agribusiness ventures. According to the findings of this study, farmers should be able to plan strategically for them to succeed in running their activities at a commercial level. It can also be concluded that good marketing skills coupled with adequate knowledge of the market for the product enhances agribusiness competitiveness. Having a foresight of the market characteristics and demands are crucial before the farmer can even start production. In addition, the farmers’ ability to promote and maintain a good brand identity is an important marketing aspect of successful agri-entrepreneurship. The study also confirms that the ease with which farmers access markets is another important prerequisite for thriving commercial agri-enterprises.It is imperative for each small scale farmer to be productively efficient and it can be concluded from this study that farmers require production skills to make it in their agricultural businesses. Production skills enhance the farmers’ ability to supply the right qualities and quantities to the market. Farmers who apply good agricultural practices and conservation farming are preferred, even on the international markets. This sparks the need for aspiring commercial farmers to improve on, for instance, the environmental friendliness aspect of their husbandry if they are to lead thriving local and international commercial entities. There is also need for small scale farmers to seek a deeper and broader understanding of global agricultural trends before they can engage in production so that they are always up to date with current issues affecting the industry in which they operate.It can also be concluded that ICT skills are paramount in modern day commercial agriculture. The study ascertained the need for farmers to acquire electronic means to store, retrieve, manipulate, transmit or receive digital data, so as to pump up their chances of success in their commercial undertakings. It also important for farmers to sufficiently grasp financial issues related to their agriculture if they are to succeed in commercial agriculture. Skills such as bookkeeping and financial reporting are crucial in tracing the direction of a business venture on a day-to-day basis. Good financial management skills also fortify the sustainability of a farm as well as broaden the farmers’ chances to realize and effectively utilize their profits. It can therefore be concluded from this study that good financial knowledge and skills coupled with access to financial resources are critical ingredients for sustainable commercial farming ventures.

6.2. Recommendations

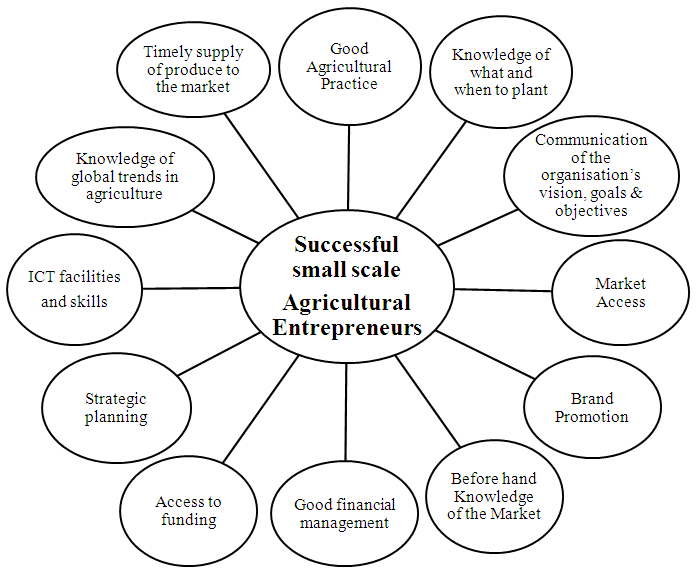

- In the light of the above discussion, the study recommends a possible entrepreneurial model for small scale farmers in Zululand District Municipality of South Africa. While there may be some generic factors that are important for an entrepreneur to succeed in agribusiness, those that require urgent attention may vary from one agribusiness person to another. The case of small scale farmers in the Zululand District Municipality presents yet another unique society of potential entrepreneurs who as a business community have their own special needs. Figure 1 summarizes the proposed entrepreneurial model that was developed in line with the findings of this study. The model was developed in an attempt to correct the needs gaps as well as assist small scale farmers in the Zululand District Municipality of South Africa to succeed in converting their farming activities into prosperous commercial ventures.Figure 1 shows that there is a wide array of attributes that are ingredient to the success of small scale aspiring commercial farming enterprises in the Zululand District Municipality of South Africa. These crucial necessities can be classified into broad categories namely, enterprise management, marketing competency, production proficiency, ICT, and financial management. It is suggested that small scale farmers be imparted in areas such as strategic planning, effective communication, financial management, marketing research and management, conservation agricultural management, ICT management and supply chain management. In addition to training, the government is advised to foster partnerships with the private sector in improving the resource constrained farmers’ access to funding, breaking their barriers to entry to both local, regional and global markets as well as installing modern infrastructure for development of the farms.

| Figure 1. Proposed entrepreneurial model for small scale farmers in the Zululand District Municipality of South Africa |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Sincere appreciation goes to Adamo Agric Business (Pty) Ltd for sponsoring this study. We would also like to extend our gratitude to Dr. Shaw for technical and general support.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML