-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2016; 6(6): 206-213

doi:10.5923/j.ijaf.20160606.02

Contribution of Mushroom to Actor’s Income in the North West Region, Cameroon: A Value Chain Analysis

Bime Mary Juliet Egwu1, Bih Akongne Asa'a2, Balgah Roland1, Kamanjou Francois2

1Department of Agribusiness Technology, The University of Bamenda, Cameroon

2Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Dschang, Cameroon

Correspondence to: Bime Mary Juliet Egwu, Department of Agribusiness Technology, The University of Bamenda, Cameroon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

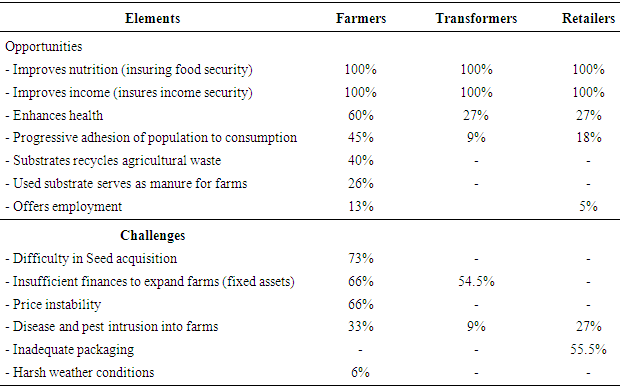

This study was carried out with the aim to analyse the mushroom value chain and its contribution to the actors’ income. Data collected from 84 sampled actors in the North West Region of Cameroon was analysed with descriptive statistics and added value calculation. The findings showed that 65.48% of the respondents were farmers, 13.09% were transformers meanwhile 21.43% were retailers. Results also revealed that various actors are involved in the production and commercialisation of fresh mushroom, dried mushroom, mushroom juice and mushroom powder. Analysis showed that the short VC is the most profitable. Also, farmers make an average net margin of 36% for the production of fresh mushroom; transformers make the least profit margin (0.42%) meanwhile retailers make an average net margin of 5.6%. Based on the actors’ perceptions, mushroom production and commercialisation offers many opportunities such as; creating employment, increasing income and ameliorating health. Meanwhile they face challenges like; intrusion of pest, high seed prices, lack of finances for expansion, competition with picked mushroom and insufficient production equipment. Mushroom production is very lucrative and as such, is a tool for generating additional income and improving food security. It is recommended that actors should merge in to Common Initiative Groups so as to reduce cost of production and government could invest more on research for more productive species.

Keywords: Mushroom, Value chain, Contribution, Income, Value added

Cite this paper: Bime Mary Juliet Egwu, Bih Akongne Asa'a, Balgah Roland, Kamanjou Francois, Contribution of Mushroom to Actor’s Income in the North West Region, Cameroon: A Value Chain Analysis, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 6 No. 6, 2016, pp. 206-213. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20160606.02.

1. Introduction

- Three out of every four inhabitants in developing countries live in rural areas and about 2.1 billion people live on less than 2 US dollars (1000 CFAF) a day while more than 880 million on less than 1 US dollar a day with a majority of these people considered poor depending on agriculture either directly or indirectly for their livelihoods [1]. The 2008 World Development Report (WDR) stresses the important role agriculture can play in achieving the first Millennium Development Goal (MDG) of reducing by half the number of people suffering from extreme poverty and hunger. The importance of agriculture in reducing poverty is also recognised by [2] who wrote that agricultural development is considered strategic for poverty reduction. Also, the 2008 WDR further draws attention to the fact that agriculture has unique features embedded in its ability to function with other sectors as an economic activity for livelihoods, to produce faster growth, to reduce poverty and to sustain the environment.According to [1] in agriculture-based economies, agriculture generates on the average 29% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and employs 65% of the labour force. Also an estimated 86% of rural people rely on agriculture for livelihood and it provides jobs for 1.3 billion smallholders and landless workers. In its attribute as a provider of environmental services, agriculture creates good and bad ecological outcomes depending on the ways natural resources and inputs (agrochemicals) are managed on and off agricultural fields. Institutions like the World Agroforestry Centre, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the Centre for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) and the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), have for some years now been researching on agroforestry options as livelihood strategies for millions of poor people all over the world, as well as provision of environmental services. A branch of these agroforestry options is the Non- Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) which comprise medicinal plants, dyes, mushrooms, fruits, resins, bark, roots and tubers, leaves, flowers, seeds, honey and so on [3]. NTFPs (also known as “minor forest products” in national income accounting system) are sources of food and livelihood security for communities living in and around forests. They are also known as Non-wood, minor, secondary, special or specialty forest products [4]. In this light, [5] defines NTFPs as “all goods for commercial, industrial or subsistence use derived from forest and their biomass”.At global level, more than two billion people are dwelling in and around the forest, depending on NTFPs for subsistence, income and livelihood security [6]. NTFPs are considered to be important for sustaining rural livelihoods, reducing rural poverty, biodiversity conservation, and facilitating rural economic growth [7]. An estimated 80 % of the population of the developing world uses Non-Wood Forest Products (NWFP) to meet some of their health and nutritional needs, [5]. Mushroom suits appropriately well in this scope.Mushroom evolves from mere picking in the forest to cultivation. The practice of cultivation for commercialisation dates back as far as 600AD in most Asian countries [8]. Literature reports that there exist more than 38,000 species of wildly grown mushrooms [9] with different characteristics. Nevertheless, only about 2000 species are edible and these species are cultivated in the world depending on the soil (substrate) type.In Cameroon, mushroom (commonly called “cocobiaco”) is regarded as meat substitute especially by the rural population. Its picking is very much practiced with the highest region being the Adamawa followed by the West region. With changes in climatic conditions picking becomes difficult bringing forth the alternative of growing mushrooms domestically. In this light, regions like the West, North West, South West, Littoral and Centre regions have pilot centers that coordinate the cultivation of mushroom, especially the production of seeds. Mushroom can be cultivated on very small piece of land (on shelves, bags, logs, bottles etc) and in large quantities using agro waste like rice husk, corn cob, saw dust etc. These substrates after cultivation are returned to soil for cultivation of other crops (biodiversity maintenance and environment friendly, [9]). To help achieve the first and second objective of the Cameroon vision 2035 (according to the GESP for 2010 to 2020 is to; increase supply of quality training, intensify agro pastoral activities as well as upgrade research), the state of Cameroon has initiated a project on mushroom cultivation captioned “Project de Développement de la Filière Champignon (PDFC)” with its headquarters at Obala. This project has been propagating the cultivation of mushroom though at a very slow rate. Nevertheless some individual farmers and organisations are greatly engaged in the production and transformation of mushroom in Cameroon especially in the Western highlands (PDFC 2012 annual report). In this light the Mushroom Production, Training and Research Center (MUPTAREC), an NGO is greatly engaged in training of farmers on mushroom growing techniques as well as supervise their activities.As an emerging market in developing countries, mushroom is very promising in its agribusiness trend but has as constraint low shelf life. To be able to overcome this constraint, the product has to be transformed to more durable products thus adding value to mushroom; this is already practiced in some developing economies. According to [10] value addition of mushroom in India represents approximately 7% (which is lower than some developing countries) and mushroom products are available as bakery products (biscuits, bread, cakes), and fast food items like burgers, cutlets and pizza etc.With the existence of both picked and cultivated mushroom, marketing the product is uncoordinated as in most local markets mushroom is sold without standard packaging and measurement; unspecified quantities as well as the qualities and the prices vary. Most at times getting the product in the market is a matter of chance, the customers have little or no knowledge as to where to get the product especially when the picking season is over. The channel is not well defined as most of the time the smallholder farmers are those who transform the mushroom and thus get to the final consumer without letting the produce pass through others agents like wholesalers, retailers and transformers who upgrade the product. This poses the problem of insufficient added value to the mushroom sold and lesser job opportunities.Meanwhile compared to other agricultural products, mushroom can create more working opportunities, help more farmers cope with their vulnerability and reduce poverty thus improving livelihood. Since it can be cultivated on very small pieces of land (According to [11], an average production of 17.5kg of mushroom can be harvested per m2 surface area) and according to MINADER, Cameroon has a 240 000ha potential of agricultural land. This activity will be a window of opportunity for other economic agents who intervene in the chain thereby adding value to -*/mushroom for the final consumer. Mushroom cultivation could be a profitable agribusiness and its incorporation into existing agricultural systems though a non conventional crop can improve the economic status of farmers as well as that of other actors involved.This study therefore aims at identifying the main actors in the mushroom value chain and the various marketing channels; determining the value added at each level of the chain and identifying the constraints and opportunities in mushroom production.

2. Methodology

- Study area descriptionThe study was carried out in The North West region of Cameroon. This region was chosen because there exists a focal point that coordinates mushroom cultivation activities in the region (MUPTAREC), which trains individual in mushroom cultivation technique, supervises and follows up mushroom farmers in the North West region. The North West Region is found in the western highlands of Cameroon. It is made up of thirty five sub divisions in seven divisions which are; Boyo, Bui, Donga Mantung, Mezam, Menchum, Momo, and Ngoketungia. This region covers a surface area of 17,300km2 and has an approximate human population of 1,845,695 thus giving a population density 105 per km2 (2010 National Census). It lies between latitudes 5° 40' and 7°, to the north of the equator, and between longitudes 9°45' and 11°10', to the east of the meridian. It is bordered to the southwest by the Southwest Region, to the south by the West Region, to the east by Adamawa Region, and to the north by the Federal Republic of Nigeria. It experiences two major seasons: A long, wet season of nine months, and a short, dry season of three months. During the wet season, humid, prevailing monsoon winds blow in from the west and lose their moisture upon hitting the region's mountains. Average rainfall per year ranges from 1,000 mm to 2,000 mm. High elevations give the region a cooler climate than the rest of Cameroon. The economy of the region is predominantly rooted in agriculture. More than 80% of the rural population depends solely on agriculture, including a strong livestock sub-sector. Food crops include rice (planted mostly in the Ndop Plain), potatoes (found in the Bui Division and Santa in the Mezam Division), beans, maize, plantains, cocoyams, cassava, groundnuts and yams are produced, and these are food staples for the region.Sample, data collection and analysis techniquesThe population (P) was the total number of actors in the mushroom value chain in the North West region who have been carrying out the activity for at least two years and also work in collaboration with the Mushroom regional pilot centre MUPTAREC. The purposeful multistage sampling technique was used in this study which permitted us to choose the group of respondents to whom questionnaires were administered. With this, out of the seven divisions, five were chosen (Mezam, Bui, Ngoketungia, Momo and Donga Mantung), from these five divisions, sub divisions with more than two actors were selected, this gave a total of 13 sub divisions with more than two actors and in this 13 sub divisions, a total of 84 actors were identified. In this study the sample size equaled the total population because the total population identified was not large thus all the actors identified were chosen. The primary data was collected by the administering of structured questionnaires to the different groups of actors as well as by field observation and discussion. Data was analysed using descriptive statistics, value added and net margin analysis show below as follows:The value added at each stage of the chain

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

3. Results and Discussion

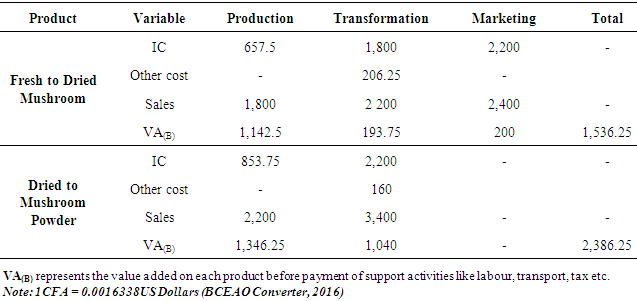

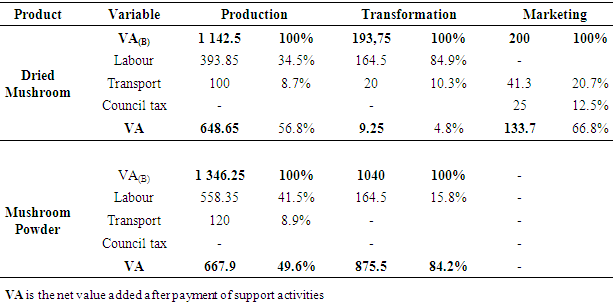

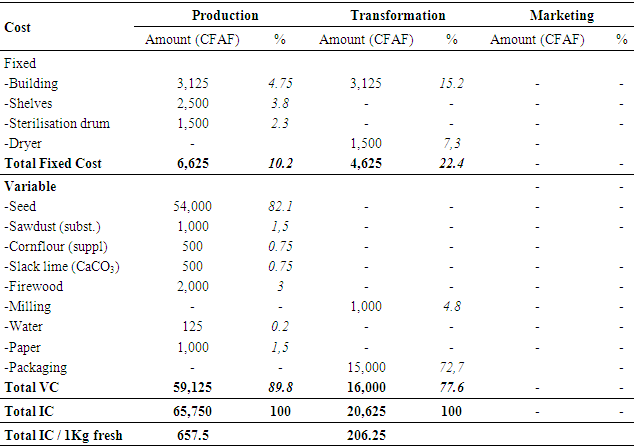

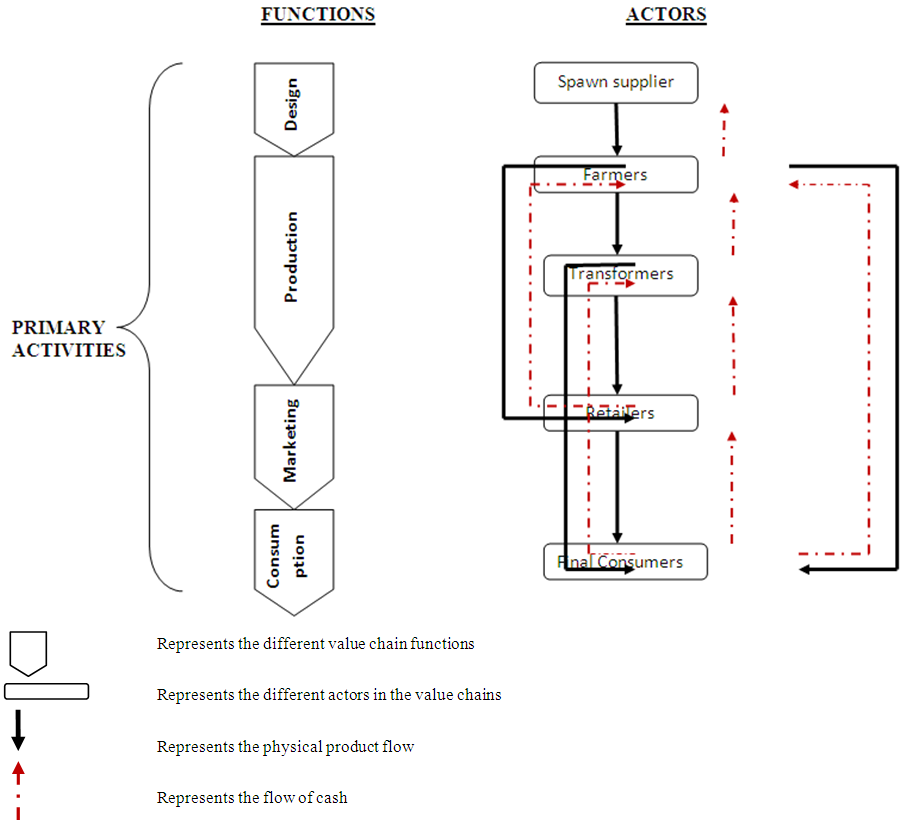

- Socioeconomic characteristicsAs any value chain has different groups of actors, so does the mushroom value chain in the North West region of Cameroon. From data collected in the field, three main groups of actors were identified and these were farmers, transformers and retailers. A total number of 84 actors were identified and surveyed. Results show that 65.48% respondents were farmers, 13.8% transformers and 21.43% retailers. A majority of the respondents were of the masculine sex with a proportion of 59.5%. It is observed that the male sex dominates in this activity because mixing the substrate requires physical strength and as such more men are involved in the growing process, nevertheless, filling of substrate and picking can be carried out by women. Results also shows that 79.8% of the respondents were married while 20.25% were not. This could be due to the fact that married people have more financial responsibility to their families and as such get involved in income diversification activities (as the case of the mushroom) to cope with their financial vulnerability. At least 40.5% of the respondents had at least a primary education. The mean age of the mushroom actors in the North West region of Cameroon was 49 years with the minimum aged actor being a farmer of 23years and the maximum 70 years. The average household size of the actors was seven (7) with the minimum being one (that is the actor has no other member in his household but himself) and the maximum 18. Since the mushroom value chain activities are considered and carried out as income diversification activities, most of the actors if not all have primary occupations. The main occupation of most actors was farming. The farmers (55.9%) were mainly involved in cultivation of crops like maize, rice Irish potatoes, cocoa, while some were involve in poultry and pig rearing.Actors of the mushroom value chain and channelsFarmers form the main group in this value chain and are at the forefront of mushroom production. Their activity is to grow mushroom from spawn (mushroom seed), to fruit body (mushroom itself). They are the ones who convey mushroom to transformers (which is used as raw material for another production), retailers and most of the times to the final consumer (either in the fresh or dried state). Cultivating mushroom takes at least four months (from substrate colonization to at least three harvest sessions); 43.6% of our respondents cultivated 3 season per annum, 25.5% cultivated twice a year meanwhile 30.9% practice just one cultivation season. This is partially in line with by [13] who found out that the average number of cultivation seasons per year in Bangladesh was 3 giving an average of 4 months. This difference can be due to the fact that the climate of the study area is very cold. With the given farm space, the mean quantity of mushroom harvested per season was 218Kg of fresh mushroom. Therefore a bag of substrate (approximately 1Kg) produces an average of 200grams of fresh mushroom per harvest. This product gets to the market either fresh or dried. The farmers sold 44.8% of their produce directly to the final consumer meanwhile 44.8% sold to the different transformers and 10.4% sold to retailers who later convey the product to final consumers.The main activities of transformers include; buying of raw material (mushroom) from farmers; change the state and the sell to customers (Retailers and consumers). In the field, there exist specificities pertaining to this group of actors. Results shows that all the transformers (100%) got their mushroom (raw material or intermediate consumption) directly from the farmers. A greater proportion (90.9%) of transformers purchased mushroom in the fresh state meanwhile 9.1% purchase in the dry state. By this, the transformers are involved in Gereffi’s GVC ‘upgrading’ dimension which has product upgrading as one option since they transform the perishable fresh mushroom to dried mushroom which has a longer shelter life. The conversion ratio for fresh- dried mushroom is 5: 1, this implies that the transformers dry 5kg of fresh mushroom to get approximately 1Kg of dried mushroom; this gives a proportion of 0.2. In the same light 1Kg of dried mushroom produces at least 17 bags of 50g each of mushroom powder.The retailers get products from mushroom farmers and transformers and then sell the product to the final consumer without any modification in the product. Their main function is to facilitate distribution of the mushroom products. Mushroom juice and dried mushroom were the two main mushroom products in which the retailers trade, 62% trade in dried mushroom meanwhile 38% trade in mushroom juice. Since this activity is mainly used to diversify income, most of the retailers trade in other products. The mushroom value chain structure identified in the study area is the simple value chain. Figure 1 shows the marketing channel and distribution structure of mushroom.

| Figure 1. Marketing channels and actors of the mushroom value chain |

|

|

|

|

4. Conclusions

- This study was carried out with the aim to analyse the mushroom value chain and its contribution to the actors’ income. The findings of the study showed that 65.48% of the respondents were farmers, 13.09% were transformers meanwhile 2.43% were retailers. The respondents were within the ages of 23 and 70 years of whom 59.5% were males. The results also showed that 79.8% of the respondents were married meanwhile only 2.4% of the respondents were uneducated and the rest having at least primary education. Also only 5.9% of the respondents had mushroom production as sole activity.The study revealed that actors are involved in the production and commercialisation of fresh mushroom, dried mushroom, mushroom juice and mushroom powder. Based on observation from the study area, there exist three main marketing chains; the short, medium and long with the most profitable being the short chain.The study shows that that farmers make the highest net margin of an average of 36% for producing fresh mushroom and 30.4% for dried mushroom, transformers make the least net margin of 0.42% for transforming fresh mushroom to dried and 25.2% for transforming dried mushroom to powder meanwhile retailers made an average net margin of 5.6% in commercializing dried mushroom. This shows that mushroom production and commercialization is profitable and as such suitable to be carried out as an income diversification activity in Cameroon. The farmers in the study area were smallholder farmers with an average production of mushroom per farm of 218Kg and added value per Kg of fresh mushroom of 654.65 CFAF. Therefore, the net profit per farm / season of 142 713.7 CFAF at the average unitary price being 1 800 CFAF was profitable.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML