-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2016; 6(4): 161-167

doi:10.5923/j.ijaf.20160604.04

Indigenous Systems of Forest Management and Beekeeping Practices: Case of Mzoghoti Village Forest Reserve, West Usambara Mountain, Tanzania

Pima N. E., Maguzu J., Bakengesa S., Bomani F. A., Mkwiru I. H.

Tanzania Forestry Research Institute, (TAFORI), Tanzania

Correspondence to: Pima N. E., Tanzania Forestry Research Institute, (TAFORI), Tanzania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

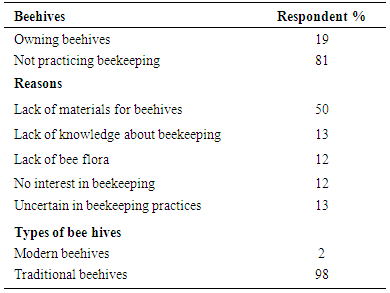

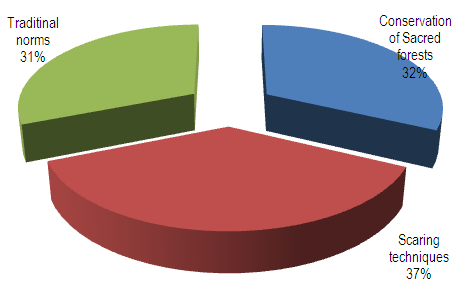

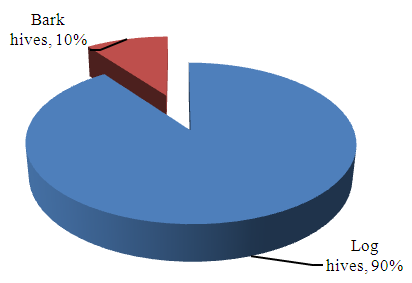

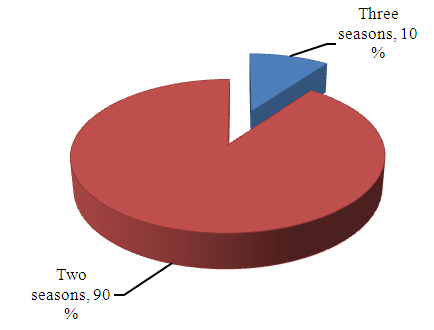

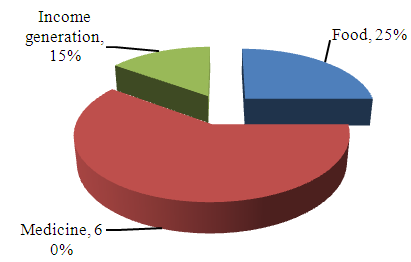

A study to assess the application of indigenous systems of forest management and beekeeping practices was conducted at Mzoghoti Village Forest Reserve in West Usambara Mountain, Lushoto District, Tanzania. Data was done in three villages namely Makose, Kilanga and Mlesa. It involved household survey, key informant interviews and focus group discussion used to acquire data from village government leadership, forest officers, elders and local communities. A sample size of 90 households obtained through simple random sampling was used. The collected data were coded and grouped for analysis. Descriptive statistics were computed using the Statistical Packages for Social Sciences (SPSS) 11.0 for Windows.Results indicated that scaring technique (37%), conservation of sacred forests (32%) practice and traditional norms (31%) were the most existing indigenous systems of forest management practiced in Mzoghoti Village Forest Reserve. Beekeeping practices were based on the use of logs (90%) and barks hives (10%). Ocotea usambarensis, Juniperus procera, Eucalyptus grandis, Grevillea robusta and Erythrina abyssinica were the tree species preferred for hives making while Albizia lebbeck, Acacia meansii, Grevillea robusta, Eucalyptus grandis, and Ficus thoningii were preferred for hanging beehives. Honey and wax were the main bee products which were used for improving livelihoods of the people around the forest reserve. It was concluded that, indigenous systems of forest management and beekeeping practices are perceived, maintained and respected by communities around Mzoghoti Village Forest Reserve and need to be scaled up in other communities of Tanzania.

Keywords: Indigenous systems, Forest management, Beekeeping practices

Cite this paper: Pima N. E., Maguzu J., Bakengesa S., Bomani F. A., Mkwiru I. H., Indigenous Systems of Forest Management and Beekeeping Practices: Case of Mzoghoti Village Forest Reserve, West Usambara Mountain, Tanzania, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 6 No. 4, 2016, pp. 161-167. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20160604.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Tanzania is endowed with large and valuable forest resources [1]. Forest goods and services have significant potential for the economic development of the country [1, 2]. Unfortunately the aggregate size of forest area continues decreasing due to deforestation. The rate of deforestation in Tanzania is estimated to be 372,871 hectares per annum which takes place in both protected and unprotected forests but mainly takes in the unprotected forests in General Land [3]. This is as a result of clearance for small scale and commercial agriculture, fuel wood, charcoal burning, building poles, logs export and uncontrolled fire [4]. Trees and shrubs in many forests have been burned and cut down and turned into ecosystems dominated by various grasses and herbs [5]. Forest loss and fragmentation are widely recognized as the two most important factors responsible for environmental degradation. The continuing forest loss is atelling measure of the imbalance between human needs, wants and nature's capacity [6]. The constantly changing forest management policies have not helped either to preserve biodiversity, or to develop forestry, instead forest ecosystems continued to be destroyed [7]. Modern forestry and beekeeping policy itself cannot lead to sustainable, productive forestry and conserve biodiversity unless it is combined with the indigenous management system of the local community and those systems should be strengthened [7]. Indigenous forest management systems and traditional beekeeping practices refer to knowledge and practices that have primarily originated locally and are performed by a community or society in a specific place for managing forest resources [8]. In addition, indigenous forest management reflects the management that has been organized by indigenous people through their traditional institutions for many years. Traditional institutions are socially embedded norms, behavior and procedures that shape how people act, in a given society [9]. This knowledge evolves and emerges continually over time according to people’s perception and experience of their environment and is usually transmitted from generation to generation by word of mouth or by practice [10]. Indigenous forest management activities and traditional beekeeping practices may originate in specific areas in response to specific pressures, but this does not prevent them from adopting and transforming appropriate components of scientific forest management systems and modern beekeeping practices through interaction and shared experiences [11].Some forms of indigenous systems continue to exist in some places despite a general belief that the nationalization of forests destroyed these systems [12]. The continuous survival of indigenous forest management systems in many locations despite the nationalization of forests was probably because of informal cooperation between communities and local officials that allowed successful forest conservation practices to continue against the national policy [7]. Indigenous knowledge plays an important role in local decision-making with regard to management of forest resources, which involves not only technical practices, but also social institutions that organize technical practices [9].Beekeeping in Tanzania plays a major role in socio-economic development and environmental conservation. Beekeeping is advocated to improve human welfare by alleviating poverty through increasing household income; it is a source of food and nutritional security, low materials for various industries, medicine and enhancing environmental resilience [6]. Beekeeping also plays a major role in improving biodiversity and increasing crop production through pollination to both cultivated and wild plants [13]. It is estimated that beekeeping generates about 1.2 million USD annually for the economy from sales of honey and beeswax [14]. It is an important income generating activity with high potential for improving incomes, especially for communities living close to forests and woodlands. For many years the practice has been very common in various parts of Lushoto district. Due to high population growth and increase pressure of human activities around forest reserves including Mzoghoti, this study was therefore conducted to assess the indigenous systems of forest management and beekeeping practices and their implication in management of Mzoghoti Village Forest Reserve in West Usambara Mountain.

2. Material and Methods

- Study area descriptionLushoto District is located between 04° 22' S - 05° 08' S, and 38° 05' E - 38°38'E within West Usambara Mountains, a part of the Eastern Arc Mountains with an area of 3,500 km2 [15]. The district has an elevation ranging from 900 to 2250 m.a.s.l. The climate is characterized by a short rainy season during November-December and a longer one during March-May with annual rainfall ranging from 600 to 1,200 mm per annum. The minimum and maximum temperatures are 13°C and 27°C, respectively. The area had total population of 492,441 people where the main ethnic groups are Shambaa, Pare, and Mbugu [16]. The Shambaa is the predominant tribe (78% of the population) followed by the Pare (16%) while Mbugu is the minority (5%) [17]. Other small groups are also found in this area accounting for only 1% of the population. People’s livelihood depends on subsistence farming. The food crops grown are maize, beans, wheat, Irish potatoes, yams, bananas, and cassava. The study was based on Makose, Mlesa and Kilanga villages around Mzoghoti Village Forest Reserve (MVFR).Sampling design and data collectionMixed sampling techniques were used. In the first stage, a purposive sampling technique was employed in selecting three villages (Kilanga, Mlesa and Makose) out of 17 villages surrounding MVFR. The selection was based on proximity to the forest. In the second stage, random selection of household within each of the three identified villages was done. A total of 30 household individuals from each village irrespective of village population size were selected. Data were collected using Participatory assessment and household survey. Household survey was conducted using structured questionnaire to complement the qualitative information from participatory assessment. A total of 90 households were randomly selected from three villages. Questionnaires were used to collect data related to; indigenous systems of forest management, existing indigenous systems, beekeeping practices (honey production, honey collection seasons and harvesting techniques) and the potential uses of beekeeping in the study area. Participatory assessment include focus group discussion (FGD) and Key informant interview. FGDs aimed at capturing information on indigenous systems of forest management and beekeeping practices and the potentials of beekeeping to livelihoods. FGDs comprised of 10 people in each village, aged above 40 years with gender consideration. The key informants were drawn from village government leaders, forest officers, and elderly people in the respective villages. The tools aimed at capturing information on indigenous systems of forest management and beekeeping practices. Data AnalysisContent method and Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) were used to analyse qualitative and quantitative data respectively. Qualitative information’s collected through verbal discussion and open ended questionnaires were broken down into smaller meaningful themes and analysed to bring statistical meaning. This helped in ascertaining attitude of the respondents. According to Kajembe [18] this technique can be used to explain the way social system and the manner in which they relate to the physical environment.Prior to data analysis using SPSS, coding was first done to summarize information based on formulated ecosystem service variables. Descriptive statistics were computed using the Statistical Packages for Social Sciences (SPSS) 11.0 for Windows [19].

3. Results and Discussion

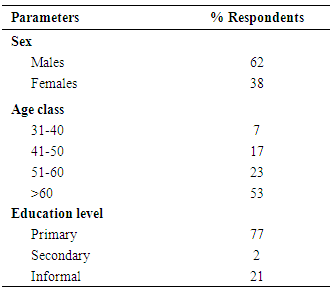

- Characteristics of RespondentsRespondents characteristics assessed include age, sex and education level (Table). This type of information is important in determining the application of indigenous forest management systems and traditional beekeeping practices on household livelihood.

|

| Figure 1. Indigenous system of forest management at Mzoghoti forest |

|

| Figure 2. Traditional beekeeping practices |

| Figure 3. Honey collection seasons |

| Figure 4. Potentials of beekeeping to livelihood |

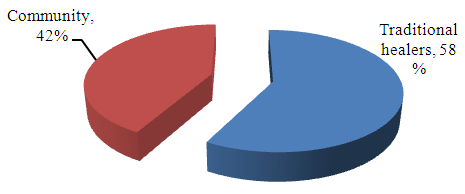

| Figure 5. Main honey customers |

4. Conclusions

- In this particular study, the main indigenous systems of forest management identified were scaring techniques, conservation of sacred forests and traditional norms. The study revealed significant role of the identified indigenous systems of forest management. The dominant traditional beekeeping practices in the study area were made from log and barks. The use of baiting hives, proper hive placement and hive management are part of traditional beekeeping practices identified. Traditional harvesting techniques such as the use of smoke of dry leaves of a selected trees and/or mushroom plant were also identified. Most of the honey collected was used as medicine, food and sources of income generation. Most of the bees’ products are available seasonally and many people lack proper knowledge on how to harvest without hurting bees and improve quality of honey. In this respect there is a need of training the communities on proper harvesting methods to ensure sustainability of the products and improved market value. The indigenous systems of forest management and beekeeping practices are perceived, maintained and respected by communities around MVFR and there is a need to consider both traditional and conventional forest resource management techniques in Tanzania.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We are highly indebted to Tanzania Forestry Research Institute (TAFORI), granted permission to conduct this research. Participatory Forest Management (PFM) Research Programme under TAFORI for financing this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML