-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2015; 5(6): 330-338

doi:10.5923/j.ijaf.20150506.05

Assessment of Aquapreneur Willingness to Pay for Mobile Phone Advisory Services in Anambra State, Nigeria

Ifejika P. I.1, Oladosu I. O.2, Asadu A. N.3, Ayanwuyi E.2, Sule A. M.1, Tanko M. A.1

1National Institute for Freshwater Fisheries Research, New-Bussa, Nigeria

2Department of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomoso, Nigeria

3Department of Agricultural Extension, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Ifejika P. I., National Institute for Freshwater Fisheries Research, New-Bussa, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

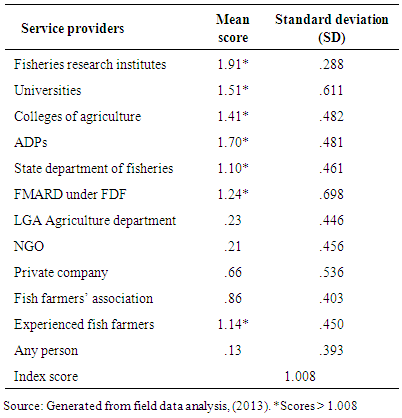

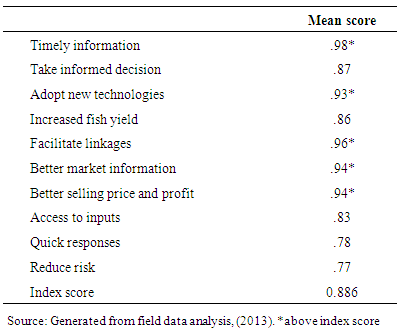

This study assessed aquapreneurs in grow out fish culture on their readiness to participate and pay for mobile phone advisory services (MPAS) to meet information need in Anambra state. An interview schedule was administered to 100 respondents to generate primary data from three zonal Agricultural Development Programmes in the state which was analysed with parametric and non parametric statistical tools. Result revealed that educated elites at tertiary levels dominate aquapreneurs. Mean scores recorded for pond ownership was (3.57), stocked fish (4,520), age (45 years) and experience (7.7 years). About 94% obliged to pay for MPAS and the consensus mean amount willing to pay was ₦48. 87. Respondents top expected gratifications for agreeing to pay for MPAS in aquaculture was to receive timely information, linkage to customers, increase profitability, better market information and to adopt technologies. Preferred credible service providers to deliver MPAS under government institutions were fisheries research institutes (1.91), Agricultural Development Programmes (1.70), Universities (1.51) and Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (1.24) whereas under private setup were experienced fish farmers (1.14) and fish farmers associations (0.86). Though, socio-economic variables contributed to 31% variation towards willingness to pay for MPAS, but age, education and experience were not statistically significant. Emerging facts from the study imply that aquapreneurs are ready to participate and subscribe to MPAS to get quality and relevant messages from credible government and private service providers. Therefore, identified relevant organisations are encouraged to initiate action on MPAS platforms to meet the information needs of target groups.

Keywords: Aquaculture, Mobile phone, ICT, Willingness, Advisory services, Nigeria, Africa

Cite this paper: Ifejika P. I., Oladosu I. O., Asadu A. N., Ayanwuyi E., Sule A. M., Tanko M. A., Assessment of Aquapreneur Willingness to Pay for Mobile Phone Advisory Services in Anambra State, Nigeria, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 5 No. 6, 2015, pp. 330-338. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20150506.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Since last decade, aquaculture production has increased the fish production with visible impact in the economy, food and nutrition security, wealth and job creation, gross domestic product (GDP), investment, income and better life for men and women aquapreneurs. According to [1], aquaculture production increased from 5.01% in 2001 to 23.61% in 2010. [2] stated that aquaculture has yielded remarkable 20% increase in growth per year with high growth in small-to-medium enterprises and a number of large-scale intensively managed fish farms. While [3] argued that aquaculture was not less paying than crops and it is capable of yielding six times more than cowpea and three times more than peanut in the same unit area. Studies carried in Anambra state on aquaculture farming were consistent on its profitability and contribution to social, economic and poverty reduction [4, 5]. For example, studies conducted in other parts of the country attested to the profitability of catfish production [6-8]. Aquapreneurs in the context of this study are commercial fish farmers that raise fingerlings to table size maturity for sale. Sustaining the booming aquaculture enterprise with investments in rural, peri-urban and urban areas requires innovative extension and advisory services delivery strategy. This is necessary as present pace of innovation and technology development in aquaculture has outpaced the knowledge level of most public extension agents, thus, making them redundant and irrelevant in their jobs as change agents and information carriers. To stress the fact, there were investigations revealing high information and training needs as a result of scarce extension activities in aquaculture aspect across the six geo-political zones of the country [9-12, 1]. Consequences of poor extension services in terms of facilitation, demonstration, training, visitation and outreach is manifested in low participation, scarce access to information acquisition and its utilisation, and low adoption of technologies by fish farmers [1]. The dearth of extension services has forced fish farmers to look inward to source information from their personal reserve as well as within networks in the value chain i.e. experience, fellow fish farmers and input sellers/dealers rather than extension agents as documented in studies by [13, 14, 1]. This issue is compounding the low investment in agricultural information [15] and its low status and neglect [16]. This inappropriate public extension scenario needs to be changed with innovative approach that is demand driven and interactive using modern information and communication technologies (ICTs) that exhibit proven track records of success. The [17] define an innovative system as a “network of organizations focused on bringing new products, new processes and new forms of organization into social and economic use, together with the institutions and policies that affect their behaviour and performance. [18] wrote that the winning approaches in modern innovative platform are in collaboration with public, private, non–governmental organisation and community based institutions. [19] stated that the rationale for private provision of agricultural services in developing countries is often based on a cost-recovery approach, which critically depend on two factors: how the extension system (public and private) provides advisory services to farmers’ satisfaction and the financial sustainability of such systems. Innovation platforms using modern ICTs like mobile phone are now the centerpiece to deliver extension and advisory services to farmers with positive results and outcomes in adoption and productivity. Fish farmers are responding quickly to the use of mobile phone as a leading ICT in terms of ownership [20] and sourcing information in the aquaculture as established by [1, 14]. In this regard, [18] reported impressive performance of the e-Sagu Aqua project, an innovative and unique model of information exchange which has been implemented in freshwater aquaculture in Andhra Pradesh State of India. Also, the success of “E-Wallet mobile phone platform” in fertilizer distribution to farmers in Nigeria under the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMARD) is convincing evidence on workability of the mobile phone driven advisory services in aquaculture. This is possible as aquaculture farmers are not technophobic as the own, subscribe and use mobile phone for communication and for other services in livelihood activities. Unit cost of information delivery with mobile phone (SMS or voice call) is cheaper compared to other media like extension agent, radio, television, personal visit, newspaper [21]. Also, mobile phone facilitates greater participation of farmers as their voices are heard, legitimises information, improve its credibility and traceability to source. Recent study by [22] established that extension agents (66.3%) and researchers (62.5%) considered mobile phone to be very effective in agricultural information dissemination. Most mobile phone driven innovative platforms require that farmers pay for service providers for sustainability. Charges for services make willingness to pay (WTP) a critical issue in ICT innovative platform. According to [23], WTP is a strong research approach that involves the targeted clients for potential services in establishing the preferences of the services proposed and the value the respondents are ready to pay. They provided definition for WTP for a service as the maximum amount of money an individual would be willing to pay for goods or services rather than do without it. According to [24] informal commercialization of extension services exist as farmers pay for transportation, feeding and other expenses pronounced by extension agents in Delta State, Nigeria. In Nigeria, explicit research works carried on WTP for extension services in different sub-sectors of agriculture were in livestock [25]; soil [26]; farmers [27]. However, study by [28] on fish farmers WTP for aquaculture extension services provided insight that full-time fish farmers were more willing to pay than their part-time counterparts. In spite of the attempt, gap still exist in literature on knowing the position of aquaculture farmers on WTP for mobile phone advisory services. Present study seeks to assess aquaculture farmers’ willingness to participate and pay for mobile phone advisory services. Specific objectives pursued were to:1. describe their selected socio-economic characteristics,2. ascertain willingness to pay for mobile phone advisory services,3. determine amount willing to pay for mobile phone advisory services,4. identify choice of credible service providers, and5. determine expected job gratifications from such services.

2. Hypothesis of the Study

- Ho: There is no significant relationship between selected socio-economic characteristics of the aquapreneur and their willingness to pay for mobile phone advisory services. H1: There is a significant relationship between the selected socio-economic characteristics of the aquapreneur and their willingness to pay for mobile phone advisory services.

3. Study Area

- Anambra State was created in 1991 and is located at 6°20′N 7°00′E in the South East geo-political zone which is predominantly industrious Igbo people. The State is bounded by five States; Delta in the east, Enugu in the west, Kogi in the north, Imo and Rivers in the south and has twenty one local government area (LGAs). The people value fish as a delicacy in various local and foreign food preparations for household or ceremonies. Local fish production from the natural water bodies and manmade ponds in the state is not enough to satisfy the rising need for fish consumption for the teeming population put at over 4million as at 2009 census figure. Though the State was categorized under low aquaculture zone in 2004 with only 18 fish farmers [29], but now, the situation has changed with more than 649 enumerated fish farmers and over 127 active registered members of the popular Catfish Farmers’ Association of Nigeria (CAFAN) at State level. Local fish supply from fishing communities in riverine areas and cultured fish farmers is inadequate to meet demand; hence, fish supply comes from other states. Popular Onitsha market in the state is a destination point for lorry loads of smoke and dry freshwater and ice fish in the country. Onitsha market receives 16,966.75 tonnes of smoked fish representing 25% of 67,867 tonnes of total fish products transported to ten urban states in the country from the Lake Chad basin, Bornu State [30]. While New Bussa and Yawuri axis’s of Kainji Lake basin in Niger and Kebbi States respectively were another export point of smoked fish to Onitsha [31]. From New Bussa axis of Kainji Lake, a 911 truck load of 400 to 500 cartons of 300 pieces of smoked freshwater fish (both pond cultured and catch from river) is exported to Ose market, Onitsha every week. Also, some pond cultured catfish sold at Ose market, Onitsha, were transported from Lagos, Oyo, Ekiti, Delta and Kwara States. This shows the high volume of fish consumption and value of fish business in the state which should not be ignored in economic development. However, restocking of various water bodies in the State particularly man-made ponds, natural ponds, lakes, reservoirs and borrow-pits in riverine communities in Anambra north senatorial district as well as development of fish farming clusters in the local government areas will increase fish production and change the dynamics of supply in the State.

4. Methodology

- The study was carried out among aquapreneurs that grow fingerlings to table size for sale otherwise called ‘table size fish farmers or grow out fish farmers’ in Anambra State. Multi stage sampling technique was used in the study and the population of the study constituted all table size fish farmers in the four zones of the State ADP which are Onitsha, Akwa, Aguata and Anambra. While the sample frame was 649 enumerated fish farmers captured in the four ADP zones by the State Fisheries Department. Next step was random selection of three ADP zones out of the four zones for the study which were Anambra, Akwa and Onitsha zones. This was followed by random selection of three blocks in each ADP zones to get nine blocks which is equivalent to nine local government areas (LGA) from the 21 LGA for the study. The sample size was a total of 146 fish farmers in the selected nine blocks representing 22.496% of the sample frame. From the sample size of 146, respondents were determined using the formulae: n=N/1+N (e) by [32, 33] The calculated respondent using the stated formulae was 106 at 95% confidence level recommendation of sample size by [32]. Finally, random sampling technique was applied to select the 106 respondents for the study. Data was collected with semi structured interview schedule through face to face interview by trained enumerators. After data collection, six of the interview schedule were discarded due to error on the part of enumerators and 100 interview schedule were validated for the analysis. Data collected from the field survey was sorted, coded and keyed into computer for analysis with SPSS version 17.0. Statistical analyses carried out were descriptive and inferential. Descriptive includes frequencies, percentages, mean, minimum, maximum and standard deviation. The mean was derived by summing up all the data values and dividing by the total number of data value (N). This was computed by using the following formula below:

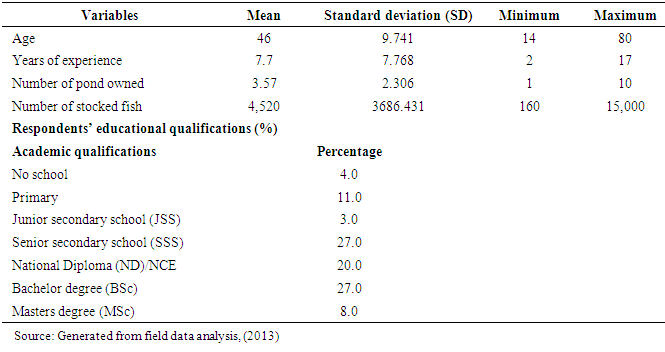

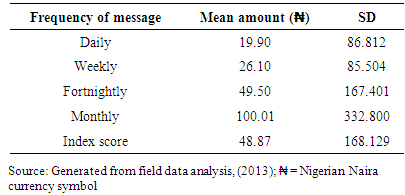

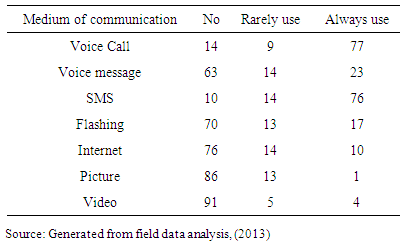

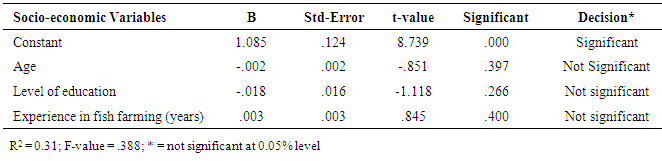

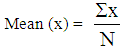

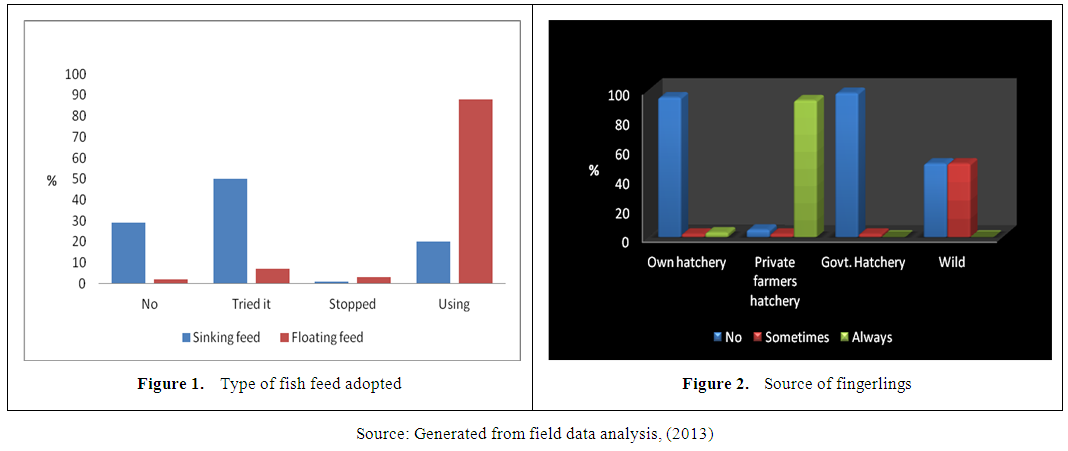

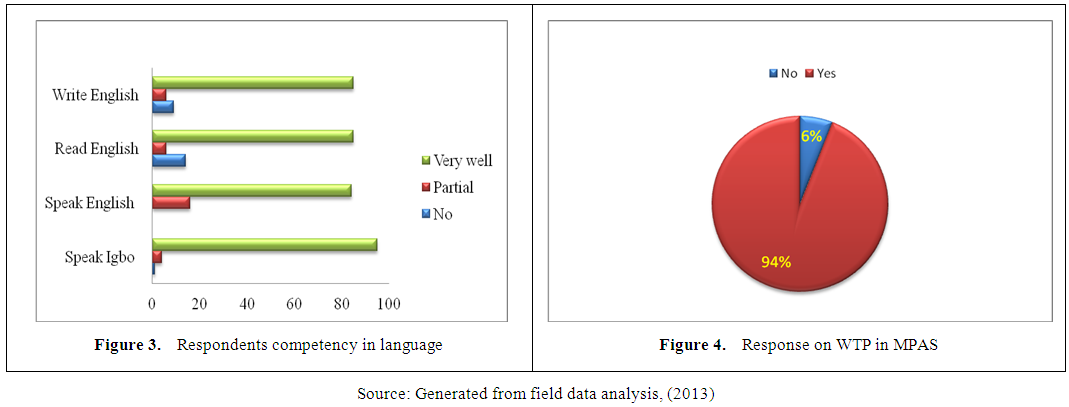

Where Σx = sum of all the data value, N = Number of data values. < mean score = low, whereas, < mean score = high.Inferential statistics was carried out with linear regression analysis for the hypothesis test. The linear regression equation is: Y = f(X1 + X2 + X3u). Where Y = willingness to pay in mobile phone advisory serviceX1 = AgeX2 = level of educationX3 = Years of experience in aquapreneurship Y is the dependent variable whereas x1, x2, x3 are the independent variables. The assumptions are that p-value for each term tests the null hypothesis that the coefficient is equal to zero (no effect). A low p-value (< 0.05) indicates that you can reject the null hypothesis. Conversely, a larger (insignificant) p-value suggests that changes in the predictor are not associated with changes in the response. Table 1 shows respondents’ personal profile with regards to age, education, years of experience as well as production indicators. As shown, the mean age was approximately 46 years while 14 and 80 years were the minimum and maximum age’s respectively. It signal that aquapreneur’s engaged in table size fish culture in the State cut across different age strata such as youth, young, middle and late adulthood with responsibilities and aspirations to fulfill. Present mean age of table size fish farmers agreed with 44.5 years obtained in the state by [34]. While on experience in fish farming, the mean score was 7.7 years which suggests that high proportion of the practicing fish farmers embraced aquaculture in the last decade. Also, the minimum and maximum years of experience were two and seventeen years respectively. It is an indication they had gained useful skills and knowledge since most of them joined the enterprise which serves as data bank for knowledge, information sources and innovative ideas. [35] established that experience serve as source of information to fingerling producers (74%) to acquire expertise and for grow-out fish farmers (51%) to learn new techniques. Information on production indicators reveals that the mean number of pond ownership was approximately four and the mean number of fish stocked was 4,520. [13, 8] found that high proportion of the fish farmers have between one to five fish ponds. It implies that grow-out aquaprenenurs in the state are investing on small scale sizable ponds for table size fish production which they can manage within their financial resources. Response on educational qualifications of respondents revealed that over half (55%) were tertiary graduates of which degree holders (BSc & MSc) accounted for 35% followed by secondary leavers (30%) and the rest (15%) were primary and no schooling. The finding on education strongly established that educated elites dominate grow out aquaculture production in the state collaborated the previous findings on the same issue in other geo-political zones of the country [36, 8]. The finding echoes’ [37] statement that since 1984, there had been a surge of interest in large – scale commercial fish farms owned and / or operated by a ‘new breed’ of influential, wealthy and sometimes knowledgeable or skilled Nigerians, whose interest in the sector had been kindled by awareness and profitability. Evidence from the socio-economic variables signifies that aquapreneurs in the study area were mostly educated adults in middle age group investing in commercial small scale ponds. Plate 1 display figures of two key inputs on fish feed adoption and fingerlings sources in commercial aquaculture production. As shown in Figure 1, majority (80%) of the respondents adopted conventional floating feed than sinking feed (20%), but, most of them tried sinking feed before the stopped its usage. In contrast with the high adoption of floating feed was [38] who found 36% usage of floating feed and 61% usage of sinking at Ijebu ode, Ogun state. However, [39] said that fish feed accounts for 60% of total cost of fish production as well as determines the viability and profitability of fish farming enterprise. This agrees with the economist finding that fish feed and fingerlings accounts for 40% to 60% resource use efficiency in aquaculture production [8, 5]. High adoption of floating feed over sinking feed can be traced to access and availability supported by the advantages of observing fish during feeding, reduction in feed wastage and low water pollution, even though sinking feed is cheaper. Figure 2 clearly demonstrated that over 90% of table size fish farmers always buy fingerlings from private hatchery operators to stock their ponds distantly followed by few from personal hatchery and government hatchery whereas over 40% source it from the wild. [40] study in Osun State reported 65% souring of fingerlings from private hatchery owners followed by government hatchery and personal hatcheries. In contrast, [41] study in Rivers state found sourcing of fingerlings mostly from government (38%), personal hatchery (32%), private (18%) and wild (10%). Sourcing of fingerlings from certified hatchery on fish that can be bred artificially is the best practice that ensures use of quality fish seed with good traits for growth. But, sourcing of fingerlings from the wild is an indication that more hatcheries are needed to meet demand for fingerlings production in the State. The wild is the only option for fish species that are yet to be bred artificially. Response on adoption of fish feed and fingerlings indicate that aquapreneurs in the State are conscious of best practices to ensure viable venture. Also, it signifies that respondents had access, invests in quality fish feed and seed inputs which are primary resources for fish growth and bumper harvest. Profitability is a function of market price. Plate 2 shows variables on language competency (figure 3) and willingness to pay in MPAS (figure 4). Communication competency of respondents in English language is critical to receive and send clear messages in MPAS. As revealed, over 70% of the fish farmers had they skill and ability to communicate through writing, reading and speaking in English language very well which is necessary to message understanding in MPAS. Respondents capability in oral and written communication in English language can be traced to their high (55%) educational qualifications at tertiary level as shown in Table 1. Therefore, English language communication competency of fish farmers was contrary to that of capture fishers who displayed low capability to written communication (write and read) as established by [42]. It implies that most respondents can easily interpret the messages they will receive in English language for their own use.

Where Σx = sum of all the data value, N = Number of data values. < mean score = low, whereas, < mean score = high.Inferential statistics was carried out with linear regression analysis for the hypothesis test. The linear regression equation is: Y = f(X1 + X2 + X3u). Where Y = willingness to pay in mobile phone advisory serviceX1 = AgeX2 = level of educationX3 = Years of experience in aquapreneurship Y is the dependent variable whereas x1, x2, x3 are the independent variables. The assumptions are that p-value for each term tests the null hypothesis that the coefficient is equal to zero (no effect). A low p-value (< 0.05) indicates that you can reject the null hypothesis. Conversely, a larger (insignificant) p-value suggests that changes in the predictor are not associated with changes in the response. Table 1 shows respondents’ personal profile with regards to age, education, years of experience as well as production indicators. As shown, the mean age was approximately 46 years while 14 and 80 years were the minimum and maximum age’s respectively. It signal that aquapreneur’s engaged in table size fish culture in the State cut across different age strata such as youth, young, middle and late adulthood with responsibilities and aspirations to fulfill. Present mean age of table size fish farmers agreed with 44.5 years obtained in the state by [34]. While on experience in fish farming, the mean score was 7.7 years which suggests that high proportion of the practicing fish farmers embraced aquaculture in the last decade. Also, the minimum and maximum years of experience were two and seventeen years respectively. It is an indication they had gained useful skills and knowledge since most of them joined the enterprise which serves as data bank for knowledge, information sources and innovative ideas. [35] established that experience serve as source of information to fingerling producers (74%) to acquire expertise and for grow-out fish farmers (51%) to learn new techniques. Information on production indicators reveals that the mean number of pond ownership was approximately four and the mean number of fish stocked was 4,520. [13, 8] found that high proportion of the fish farmers have between one to five fish ponds. It implies that grow-out aquaprenenurs in the state are investing on small scale sizable ponds for table size fish production which they can manage within their financial resources. Response on educational qualifications of respondents revealed that over half (55%) were tertiary graduates of which degree holders (BSc & MSc) accounted for 35% followed by secondary leavers (30%) and the rest (15%) were primary and no schooling. The finding on education strongly established that educated elites dominate grow out aquaculture production in the state collaborated the previous findings on the same issue in other geo-political zones of the country [36, 8]. The finding echoes’ [37] statement that since 1984, there had been a surge of interest in large – scale commercial fish farms owned and / or operated by a ‘new breed’ of influential, wealthy and sometimes knowledgeable or skilled Nigerians, whose interest in the sector had been kindled by awareness and profitability. Evidence from the socio-economic variables signifies that aquapreneurs in the study area were mostly educated adults in middle age group investing in commercial small scale ponds. Plate 1 display figures of two key inputs on fish feed adoption and fingerlings sources in commercial aquaculture production. As shown in Figure 1, majority (80%) of the respondents adopted conventional floating feed than sinking feed (20%), but, most of them tried sinking feed before the stopped its usage. In contrast with the high adoption of floating feed was [38] who found 36% usage of floating feed and 61% usage of sinking at Ijebu ode, Ogun state. However, [39] said that fish feed accounts for 60% of total cost of fish production as well as determines the viability and profitability of fish farming enterprise. This agrees with the economist finding that fish feed and fingerlings accounts for 40% to 60% resource use efficiency in aquaculture production [8, 5]. High adoption of floating feed over sinking feed can be traced to access and availability supported by the advantages of observing fish during feeding, reduction in feed wastage and low water pollution, even though sinking feed is cheaper. Figure 2 clearly demonstrated that over 90% of table size fish farmers always buy fingerlings from private hatchery operators to stock their ponds distantly followed by few from personal hatchery and government hatchery whereas over 40% source it from the wild. [40] study in Osun State reported 65% souring of fingerlings from private hatchery owners followed by government hatchery and personal hatcheries. In contrast, [41] study in Rivers state found sourcing of fingerlings mostly from government (38%), personal hatchery (32%), private (18%) and wild (10%). Sourcing of fingerlings from certified hatchery on fish that can be bred artificially is the best practice that ensures use of quality fish seed with good traits for growth. But, sourcing of fingerlings from the wild is an indication that more hatcheries are needed to meet demand for fingerlings production in the State. The wild is the only option for fish species that are yet to be bred artificially. Response on adoption of fish feed and fingerlings indicate that aquapreneurs in the State are conscious of best practices to ensure viable venture. Also, it signifies that respondents had access, invests in quality fish feed and seed inputs which are primary resources for fish growth and bumper harvest. Profitability is a function of market price. Plate 2 shows variables on language competency (figure 3) and willingness to pay in MPAS (figure 4). Communication competency of respondents in English language is critical to receive and send clear messages in MPAS. As revealed, over 70% of the fish farmers had they skill and ability to communicate through writing, reading and speaking in English language very well which is necessary to message understanding in MPAS. Respondents capability in oral and written communication in English language can be traced to their high (55%) educational qualifications at tertiary level as shown in Table 1. Therefore, English language communication competency of fish farmers was contrary to that of capture fishers who displayed low capability to written communication (write and read) as established by [42]. It implies that most respondents can easily interpret the messages they will receive in English language for their own use.

|

| Plate 1. Response on adoption and sources of key production resources inputs |

| Plate 2. Responses on language competency and willingness to pay in MPAS |

|

|

|

|

|

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The study provided explicit insight on aquaculture farmers’ willingness to pay for MPAS. Expression of table size fish farmers justified their readiness to share in the cost of providing information through mobile phone platform to enhance effectiveness of extension, production output and marketing. Interestingly, amount willing to pay for MPAS was the prevailing charges for similar services. Based on the revelations of this study, it is recommended that identified government and private agencies should initiate actions towards making MPAS a reality in the State.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML