-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2015; 5(2): 138-145

doi:10.5923/j.ijaf.20150502.07

Attitudes of Local Communities towards Forest Management Practices in Botswana: The Case Study of Kasane Forest Reserve

1Botswana College of Agriculture, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana

2Okavango Research Institute, University of Botswana, Maun, Botswana

Correspondence to: J. P. Lepetu, Botswana College of Agriculture, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Positive attitudes of local communities towards collaborative forest management are an essential prerequisite for local participation in forest management. The purpose of this study was to assess the attitude of local communities towards forest management practices in Botswana and Kasane Forest Reserve (KFR) was used as a case study. In Kasane Forest Reserve, local communities have been restricted some resource utilization since this area was declared a Protected Area in the 1960’s. This has resulted in mistrust, antagonism and conflicts with the Forest Department. Data for the study was generated through household survey comprising of 237 respondents selected through simple random technique. Logistic Regression model was used to assess the effect of socio-economic and demographic factors on the households’ willingness to participate in forest management. The study findings revealed that, generally the respondents held positive attitudes towards KFR. The results also depicted the association between socio-economic features of people living close to the forest and their use of forest resources and demonstrated the basis of attitudes towards those managing the forest. Since Botswana is going through the process of decentralising natural resources management, it is felt that local communities could be empowered to co-manage and benefit from forest resources in their vicinity.

Keywords: Attitudes, Local communities, Forest management practices, Collaborative forest management

Cite this paper: J. P. Lepetu, H. Garekae, Attitudes of Local Communities towards Forest Management Practices in Botswana: The Case Study of Kasane Forest Reserve, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 138-145. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20150502.07.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

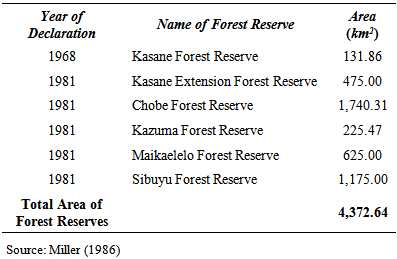

- Gazetted forests in Botswana are managed and protected by the state. In many parts of the world, state management of forest reserves has been criticized for ignoring local community participation in forest management and failing to recognize local communities’ needs for forest products [1], [2]. In a situation in which little consideration was given to the people’s long term needs, local people lose the feeling of owning the forests and develop negative attitudes towards them [3]. This in turn leads to indiscriminate exploitation of forests, degradation and deforestation.Historically, restrictions on forest resource use have been practiced by some traditional societies, for example, in the sacred forest groves of Ghana and former royal hunting areas in Zambia (Ntiamda-Baiud et al cited in Obua, Banana and Turyahabwe [4]). While most forest management policies may reflect genuine concern for the preservation of natural forests, it is also evident that little regard has been given to the subsistence needs of local people, thus causing local resentment. Given the historical antecedents of today’s gazetted forests in Africa, it is not surprising that the attitudes of local people living adjacent to forest reserves reflect suspicion and mistrust on forest management policies.Management of forest reserves for the sustainable supply of forest products and provision of environmental benefits is a key aspect of Botswana’s forest management practice. The northern part of the country is characterized by open woodland of hardwoods such as Baikiuea plurijuga and Pterocarpus angolensis and the majority of these hard woods are located in Forest Reserves. Derivation of these products (Baikiuea plurijuga and Pterocarpus angolensis) from forest resources continues to be under great pressure due to human activities; particularly wood which has major contribution of fuel energy used in the country. Some of the major human activities that contribute to this depletion are land use for settlement and infrastructure development, arable and pastoral agriculture, cutting of live wood resources for building poles and fencing material for kraal and homes. These factors together with frequent adverse climatic conditions, bush fires as well as increasing populations of both domesticated and wild animals contribute significantly towards the denudation of forest resources in the world as illustrated in Table 1.

|

2. Forest Policies and Strategies

- For a long time the forest sector in Botswana has been relatively unimportant and undeveloped. However, more recently forestry planners are beginning to consider forestry a possibility for economic diversification, especially as diamond mining which is the mainstay of the economy is a non-renewable resource. In reality, Botswana has been ineffective in managing or protecting the forest resources, or making this sector of much economic significance. The country is still in the process of implementing its new forest policy which is still awaiting debate and approval by the national parliament. The 2000 National Forest Policy draft reflects many of the principles of collaborative forest management and the need to work with communities but most of the statements are rhetorical and unclear about how to pursue this approach or specifically how communities would participate in this collaborative approach. Botswana’s 1968 Forest Act has not been reviewed and its laws have not been enforced. The Act was designed to ensure some protection and administration of forest reserves and state land (25% of the country). Since then there has been growing conflict between the Forestry Department and local communities especially over forest reserves established in tribal lands since the Act restricts the local communities from pursuing their normal traditional activities. The six gazetted forest reserves (Table 1) make about 0.8% of the total land area of the country. The reserves were created primarily to safeguard valuable timber resources. The resources are therefore not open to any exploitation without prior permission from the Forestry Division. On the other hand, in the communal areas, the natural woodlands are a free access regime and can be harvested for use or traded within and between settlements.The forests and woodlands of Botswana represent an important resource in terms of providing the majority of rural populations with an energy source, materials for fencing, construction, building, crafts and maintaining environmental balance. Chobe Forest Inventory and Management Plan, [6] estimated that there are 419,800 ha of forest reserves in Chobe District, containing invaluable timber resources of forest of Mukusi (Baikiaea plurijuga), Mukwa (Pterocarpus angolensis) Mophane (colophospermum mophane). These reserves also contain a range of ecosystems including miombo woodlands, grass and bush savannah, as well as river and flood plain habitats. Wildlife abounds in the area and many other non-wood forest products. In the villages that are surrounded by forests, a varied set of cultural systems exist based upon the exploitation of these different ecosystem.According to Kiss [7], new approaches to forest management that emphasize local community participation need to be introduced as a measure for reducing mistrust and conflict between local communities and forest managers. In Botswana, which is famous for implementing Community Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) by the Wildlife sector, community forest is a new concept. Therefore, there is need to develop mechanisms for involving local people in forest management.

3. Description of the Study Area

- The Chobe District is one of the smallest districts in Botswana and has an international setting. It is located in the extreme northern part of country where Botswana shares boundaries with, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The district has a total land area of 22 559 km2 of which 17 831 km2 is the total land area of the Chobe National Park and the six forest reserves [8]. The District lies within the lines of longitude 24°E and 26°E, and the lines of latitude 17° 45’ and 19°S.The study area, the Kasane Forest Reserve (total land area 1 360 km2) is one of the six gazetted forest reserves in Botswana (Forest Act, Chapter 38:04, 1968) all of which are located within the Chobe District. The forest reserves were originally created to protect areas containing valuable timber-sized trees for logging operations under Concession agreements [9], [6]. However, due to the dwindling supply of commercially exploitable timber trees, the logging operations were suspended in 1988 [6]. The KFR is located at the extreme northern corner of the country, adjacent to the Zimbabwe international border and very close to Chobe River, which is also an international boundary between Botswana and Namibia. The reserve is bounded to the north by the Kasane town and Kazungula village, Zimbabwe to the east and Chobe National park to the west [10]. The total annual rainfall for the district is 500–600 mm, which is the highest in the country.

3.1. Vegetation

- Chobe forests contain the only deciduous woodlands in Botswana. The forest vegetation and associated fauna is part of the Zambezian biogeographical region. In Botswana, Chobe is the only district where the rainfall is just adequate to support more or less closed canopy forest vegetation [6]. The Mukusi (Baikeaea plurijuga) forests represent the southernmost extension of the natural range of this species, which is geographically restricted from southern Angola eastwards through southern Zambia to western central parts of Zimbabwe. This vegetation type has a wide distribution throughout sub-Saharan Africa and contains a large number of deciduous tree species, all of which are more or less adapted to periodic fires, low and erratic rainfall.

3.2. Fauna

- The fauna in this part of Botswana is characterized by its forest habitat affinity and has a wider distribution further north. Although not only restricted to Chobe, some 40 to 50 species of birds are mainly confined to this forested part of the country as either permanent inhabitants or winter migrants [6], [11]. Forest-adapted wildlife species of particular importance for conservation and with potential for sustainable utilization are sable antelope (Hippotragus niger), roan antelope (Hippotragus equinus) and greater kudu (Taurotragas oryx). Because the area has not yet been adequately studied with respect to total fauna and biodiversity composition, it is not yet known if the forest reserves contain other endangered or rare species that require special conservation measures. The Chobe district now harbors one of the largest and most dense population of elephants on the African continent [6], which is estimated at approximately 100,000-120,000 [8]. The international concern for the worldwide conservation and restrictions on the trade of products of elephants has exacerbated the management problems of this species in Botswana.

3.3. Potential Threats

- Although all forest reserves are equally important from an ecological point of view, the KFR will always be most affected by any development plans. This is because of its proximity to the town of Kasane, and the villages of Lesoma and Kazungula. In addition, the forest reserve has a well developed road network and therefore experiences a lot of human pressure in the form of tourism, private investors, expansion of villages and government installations. The number of threats to the future existence of the KFR is increasing. Apart from the biological threats of the forest such as fire and elephant damage [12], [13], large areas of the forest (about 3060 hectares) have already been de-gazetted for residential purposes of the Kasane town and the expansion of the Kasane airport in 2002.Land encroachment poses an even greater threat to wildlife conservation because the KFR acts as a buffer zone for the Chobe National Park, which is already under immense pressure from the large elephant population. Discussions with the Department of Forestry and Department of Tourism in Kasane [14] revealed that a lot of pressure is exerted on the Regional Forestry Office in Kasane by different hotels and enterprises who want to conduct mobile tourist safaris and similar activities in the forest reserve. The over-crowding by tourists in the Chobe National Park seems to be the main reason for justifying their interest in opening up the forest reserves for conducting tourism operations.

3.4. Study Villages, Their Historical and Socio- economic Context

- For the purposes of this study, three communities of Kasane, Kazungula and Lesoma that surround the KFR are considered. According to the 2001 census records of Botswana, the population of this area is approximately 10 247, more than half of the total (18 258) for the Chobe District population. This area has one of the highest population growth rate in the country of 4.03% compared to the national average of 2.38% [15]. According to the Central Statistics Office [15] Kasane Township in 1991-2001 recorded the highest population growth rate (6.46) percent in the country. The village of Kazungula was established by the Wenela Agency in 1935 to recruit workers for the mines in South Africa, which also started a forest logging industry from the Chobe forests. With the establishment of the clinic and school around 1945 and 1949 respectively, the settlement rapidly expanded and people started cultivating crops. The KFR was established in 1968 on the northern edge of the settlement [9]. In 1969, Wenela closed its office in Kazungula and many people who originated from Zambia returned to their home country. The start of the liberation war in neighboring Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) with its frequent cross-border incursions, forced some people to move to nearby Kasane. The Lesoma village is completely surrounded by protected areas, which include the Matetsi Safari Area on the Zimbabwean side and the gazetted forest reserve in Botswana. The first recorded settlement was in the 1860s around a semi-perennial spring on the valley floor around which cultivation has continued to the present-day. The bulk of the village is located within the KFR following the movement of people away from the international border due to cross-border incursions in the mid and late1970s at the height of the liberation war in neighboring Rhodesia. In 2000, the Forestry department negotiated a land swap with villagers and the District Authorities. This re-aligned the KFR boundary further away from the Lesoma village. The population of Lesoma has grown from 234 in 1991 to 454 in 2001 [15]. On the other hand, Kasane is not a traditional village, but was established around Government Offices of the District Commissioner, District Police Officer and the Forest Officer in the 1950s [9]. Kasane (and to a lesser extent Kazungula) is made up of people of varied ethnic and social groups. Many inhabitants have migrated on a permanent or temporary basis from the other villages in the District into Kasane. In addition to a number of government officers, a number of expatriates are staying in the district, mostly involved in the tourism sector and arable farming. There is improved infrastructure and good housing, although there is shortage of land as the area is surrounded by the Chobe National Park, the Chobe River and the forest reserves. The implication of this migration is that unemployment in Kasane continues to rise [8].

4. Methodology

- Methods of assessing people’s attitudes and behavior are well documented in the social science literature [16], [17], [18]. Generally, the manner in which local people use forest resources and react to forest rules determines their social behavior and attitudes towards the forest. According to Gross [5], there is a relationship between one’s attitude and behavior. Therefore, it might be possible to predict his/her behavior. But attitudes can only be used to predict behavior when appropriate measurement techniques are used. In this study, it was felt that in order to predict whether local communities living adjacent to KFR would participate in a collaborative management program, their use of forest resources and attitudes towards forest management practices need to be known.

4.1. Data Collection

- The field data were collected between April and August 2005. A preliminary study, which included field visits to the Chobe district in Botswana, was undertaken during May – July 2004. Discussions were held with the village heads of Kasane, Kazungula and Lesoma, Civil servants, the KFR staff, and African Wildlife Foundation (an NGO) to gain an idea of the magnitude of the problems involved in the management and conservation of forest reserves.

4.2. Selection of Respondents

- Kasane, Kazungula and Lesoma, the three villages surrounding KFR where the study was conducted, have a total of 2657 households [15]. From this, a sample size of 237 households was selected which was approximately about 10% of population size. Within the selected villages, a list of the households was acquired from the District Council Offices from which a simple random sample was applied to select households. Sampling was done by writing down names of residents’ households on pieces of paper and these were put in a box from which names of the household owners were drawn at random based on the location of the wards. The choices of respondents based on the location of the wards were done in order to ensure equal chances of selecting different land uses around the PA (arable farmers, livestock farmers, tourist operators) and location-specific factors (e.g., distance to the Protected Areas). Where the household owners were unavailable, it was not possible to go back to visit the household in the evening for fear of wild animals; therefore in such cases, where the head of the chosen household was not available at home, the adjacent or a nearby household was selected.

4.3. Survey Design

- The survey instrument contained both close and open ended questions. The questions asked were related to resource use, perceptions, the demographic characteristics and socio economic data. The data on household characteristics included (gender, age, household size, residency and education [ability to read and write, none-formal, primary, secondary and tertiary level] and occupational data). Attitude questions concerning the forest resource use were phrased around the benefits from the forest (in terms of collecting forest products), restrictions on resource use, burning of the forest, because these are considered the contentious issues in the KFR [9], [6]. Respondents answered each attitude statement according to their strength of agreement by the following level scores: 5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = don’t know, 2 = disagree, and 1 = strongly disagree [19]. Scaling was reversed for unfavorable statements such that higher scores indicated higher levels of awareness of environmental issues and more favorable attitudes towards conservation. Open ended questionnaires were used to solicit information of forest management practices, specifically the following:● willingness to participate in forest management● prerequisites to reducing forest use by the community

4.4. Administration of the Survey

- With the help of University of Botswana in Gaborone, four local research assistants conversant with the local language were employed after undergoing an interview. They were trained for 2 days before administering the survey. Survey questions were translated into Setswana, which is Botswana’s local language. A pre-test survey was conducted with 20 respondents to check whether the questions asked were clear to the respondents as well as to the enumerators. This helped to understand how well the question suited the local setting, if the questions were easy to understand, and how long the interview would take. This was also part of training for the enumerators. After pre-testing, some questions were modified as necessary.

4.5. Data Analysis

- Survey data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social of Sciences (SPSS Version 12). Descriptive statistics was used to summarize the data. From the theoretical framework, the decision to predict those people who are either willing or not willing to participate in forest management make the choice of a logistic regression a more appropriate tool for this analysis. Therefore, Logistic Regression model [20] was used to assess the effect of socio-economic and demographic factors of the households’ willingness to participate in forest management. The model is represented as:

p = probability of an individual saying ‘no’ (0 = unwilling) or ‘yes’ (1 = willing) to participatory forest management. In using the model, it is assumed that the probability that an individual supports participatory forest management is independent of their demographic and socio-economic characteristics, i.e,

p = probability of an individual saying ‘no’ (0 = unwilling) or ‘yes’ (1 = willing) to participatory forest management. In using the model, it is assumed that the probability that an individual supports participatory forest management is independent of their demographic and socio-economic characteristics, i.e, | (1) |

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Demographic and Socio Economic Characteristics

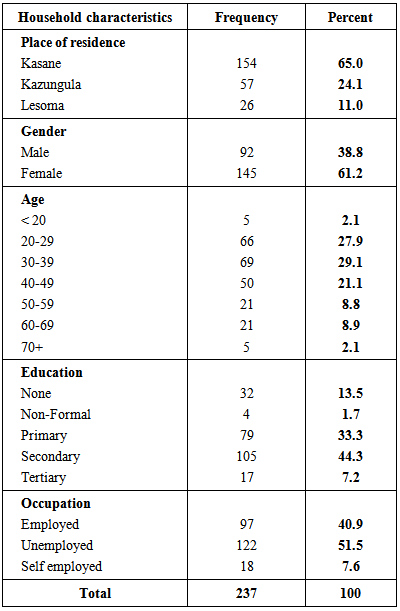

- The survey of the households shows a great deal of variation in resource endowments, demographic and geographic factors. The majority of the respondents were from Kasane 154 (65.0%), followed by Kazungula 57 (24.1%) and Lesoma 26 (11.0%). More females were interviewed 145 (61.2%) compared to 92 (38.8%) males. The majority 185 (78.1%) of the respondents were aged between 20 and 49. With regard to education status, those with Secondary education constituted the majority 105 (44.3%) of the sampled population followed by those with Primary education 79 (33.3%) and those with no education at all 32 (13.5%). However, those with non-formal education and tertiary education were less than 10%. The respondents were mostly unemployed 122 (51.5%) followed by those employed 97 (40.9%) either by government or tourism related enterprises and the self employed 18 (7.6%) (See table 2 for details).

|

5.2. Forest Resource Utilization

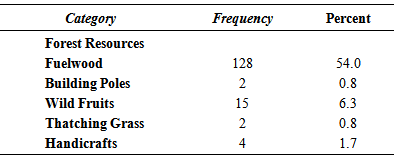

- As in most other parts of the country and in this region in particular, firewood is still one of the most important source of household energy (Table 3). However, only 138 (58.2%) of the households reported ever going into the forest reserve. The use of building poles and thatching grass has declined significantly in the study area as compared to a decade ago [9]. This is shown by a shift towards corrugated iron roofing by households in the study area (personal observation). Although there is widespread selling of handicrafts to tourists by both men and women at the market place (personal observation), all of these products were bought from traders from the neighboring countries of Zimbabwe and Zambia and others from the neighboring remote areas of the Chobe Enclave. Residents attribute this to the scarcity of local material for making handicrafts in the KFR. Residents also felt that the availability of fruits was declining due to an increased population in recent years of elephants and baboons which either damage the trees or pick the fruits before they are ripe for human consumption. Thatching grass is becoming more difficult to find due to the lack of annual early burning to promote fresh vigorous growth in the next growth season. According to villagers in the survey, this was due to disagreement between the Forestry Department and the local people on certain management decisions such as the timing of early burning.

|

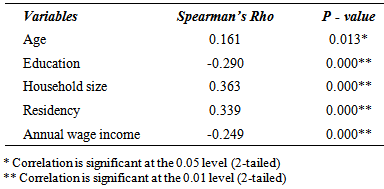

5.3. Correlation of Selected Households’ Variables with Forest Income

- A Spearman rho correlation coefficient was calculated for the relationship between dependent variable forest income and selected households’ explanatory variables. This is a non parametric procedure that determines the strength of the relationship between two variables. A significant correlation indicates a reliable relationship, but not necessarily a strong relationship. With enough subjects, a very small correlation can be significant. Generally, correlations greater than 0.7 are considered strong. Correlations less that 0.3 are considered weak. Correlations between 0.3 and 0.7 are considered moderate.

|

5.4. Attitudes and Management Opinions about KFR

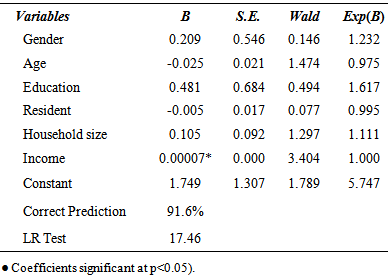

- Attitudes were examined using the responses of the respondents on the 1 to 5 Likert Scale. The mean attitude index was 3.98 and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.69 suggesting that it was truly additive and reflective of overall attitude. These results indicate that the local people were generally more positive towards the forest reserve, which is similar to other findings by [21] in Ecuador; [22] in Mozambique and [23] in Cameroon. In general on a scale of 1 to 4 (least important to most important) 48.5% of the respondents ranked the limited land issue as the most important problem facing the community living around the KFR, followed by livestock predation (41.85%) and wildlife damage on agricultural crops (36.3%). Lack of access to forest products is perceived by respondents (72.2%) as the least important problem faced by the community. Although local communities are allowed to extract traditional non-timber forest products for subsistence use, they require a permit to harvest these products for commercial purposes. Regarding the question of whether the management of KFR was satisfactory, 34.6% perceived it to be unsatisfactory, while 13.5% had no opinion and 51.9% perceived it to be satisfactory. In addition, the majority (91.6%) of the respondents suggested that local communities should participate in the management of the KFR. Their major reasoning was that as beneficiaries (82.3%) they need to be involved, while only 8.4% based their justification for participation on the fact that they possess some management skills. When taken together, these responses indicate a desire by the community for greater participation in management of forest resources.The logistic regression results (Table 5) showed that apart from income, all other demographic and socio economic characteristics of the households did not significantly influence their decisions to participate in the management of Kasane Forest Reserve. The results show that the model predictions are correct 91.60% of the time indicating that the explanatory variables can be used to specify the dependent variable, in discrete terms (1,0), with a high degree of accuracy. However, Odds ratios for these variables indicate little change in the likelihood of participation in forest management.

|

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- This study has attempted to explore how local communities’ use of forest resources, user rights and demographic/socio-economic characteristics can influence their attitudes towards forest management practices. A majority of the people agreed that KFR should be conserved, and more than 80% asserted that as beneficiaries of the forest, they need to be involved. When a follow up question asked how local community should take part in conservation, many respondents gave example of taking part in management decision making or undertake forest conservation projects, e.g. tree planting. Local attitudes were probably determined by local expectations expressed as possible gains and losses in the future due to the establishment of tourism projects. The choice for participation in forest management by most community members in this study is similar to a study reported by [24] in Kwazulu-Natal in South Africa. However, these studies are in contrast to attitudes expressed by some other South African forest communities. For example, [25] found that forest users in the Eastern Cape Province displayed weak support for Participatory Forest Management and strongly supported State Forest Management. Likewise, 89% of interviewees around Thathe forest (Limpopo Province) felt that the State was better placed to manage forests than the community, although 43% supported Participatory Forest Management initiatives (Sikhitha 1999 in [25]). As shown by the results, positive relationship between participation and household income suggest that if people have other sources of income, they are likely to participate in forest management. Furthermore, the inverse relationship between forest income and total household income (income from salaried, wage employment, remittances and others) suggest that forest products collection is not a preferred vocation , but rather taken up in the absence of regular sources of income. Such results are not unique to this study; other studies have also concluded that people prefer alternative vocations to forest products collection. The apparent desire of local population to be included in the KFR’s management, which is consistent to the proposed national forest policy draft directed at participation of rural communities surrounding Protected Areas, poses some basic questions:● To what extent can the resources be exploited? Which resource?● Will subsistence hunting of wildlife be allowed in KFR in the near future, since wildlife hunting in Forest Reserves is not allowed?● How should the participation of rural communities in the management of KFR be structured?A balance must be found between conservation and sustainable utilization. Knowledge of biological productivity and sustainable yields of forest products is lacking and this should be acquired before implementing such policy. It will be necessary to quantify resource availability, production and use in a carrying capacity analysis. Proportional participation is important to enable minority issues to be incorporated into projects, as people differing in needs are likely to act according to perceptions of their best interest. For any resource conservation initiative to be effective, the initiative should incorporate and work within the existing social environment. Discussions with the different local communities should be initiated, as a first step to giving them managerial power and responsibilities over available resources. A prerequisite for such an approach would be a well-structured Forestry Department with a clear conservation policy, and an efficiently-functioning field staff, but this still requires attention in the case of Botswana. There is a long way to go in this endeavor for local people participation in KFR, but Botswana has other successful programs (e.g. Community Based Natural Resource Management initiated by the wildlife sector), and thus there are models upon which to base such a scheme. As stated earlier, households who have some form of income are more likely to participate in forest management. The Forestry Department should therefore provide alternative income generating options such as ecotourism which will act as incentive for local communities to participate in forest management. This is particularly so because of the small sized nature of the Forest Reserve and its associated negative pressure such as fire and elephant damage. Working with communities in a truly participatory way is a relatively new function for Foresters the world over [26], and Botswana is no exception. It is recommended that detailed feasibility studies be undertaken prior to the implementation of Participatory Forest Management. This will place the government in a better position to plan a pragmatic approach to offset any challenges that may be later encountered. Such studies could highlight the various types of heterogeneity that exists within stakeholders and how they can be harnessed and managed to ensure that they work for the program. Thakadu [27] reported that lack of feasibility studies deprived the success of CBNRM implementation in Botswana. Therefore, caution should be taken not to dismiss state forest management quickly because it is too ‘protectionist’ without any bases on feasibility studies that can inform the Department of Forestry on how best to manage the differences among local communities.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML