F. O. Idumah, Owombo P. T., U. B. Ighodaro

Moist Forest Research Station, Forestry Research Institute of Nigeria, Benin City, Nigeria

Correspondence to: F. O. Idumah, Moist Forest Research Station, Forestry Research Institute of Nigeria, Benin City, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

This study was carried to determine the economics of yam production under agroforestry system in Sapoba forest area, Edo State, Nigeria. Sixty farmers were purposively selected. Cobb-Douglas production function was used to estimate the coefficients of the various variables analyzed. MPP, MVP and allocative efficiency index were used to estimate the efficiency of resource use in the study area. The results showed that farm size, yam seed and years of farming were significantly positive to yam production in the area. The results of the efficiency estimation, however, indicated that farm size (1.55), yam seed (1.5) were underutilized while hired labour (0.24), hoes (0.46) and matchete (0.32) were over-utilized. The regression also showed that the farmers were in the first stage of production which is increasing return to scale (using the elasticities). The study therefore recommends that farmers should be encouraged to increase their productivity and, by extension, profit by the provision of improved yam seed. They should also maximize the utilization of the farm land by increasing the number of yam sett planted per hectare.

Keywords:

Efficiency, Agroforestry, Yam, Sapoba forest area, Nigeria

Cite this paper: F. O. Idumah, Owombo P. T., U. B. Ighodaro, Economics of Yam Production under Agroforestry System in Sapoba Forest Area, Edo State, Nigeria, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 4 No. 6, 2014, pp. 440-445. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20140406.04.

1. Introduction

Yam belongs to the genus “Dioscorea” and family “Dioscoreaceae”. It is an important tuber crop of the tropics and some other countries in East Asia, South America and India (Iwueke et al, 2003). Yam (Dioscorea spp) is among the oldest recorded food crops and ranked second after cassava in the study of carbohydrates in West Africa (Agwu and Alu, 2005). There are over 600 species of yam worldwide but six species can be considered as the edible ones in the tropics. These are white yam (Dioscorea rotundata) yellow yam (D. cayenensis), water yam (D. alata), trifoliate yam (D. dumentorum), arial yam (D. bulbifera) and Chinese yam (D. esculenta). Yam tubers are eaten boiled, roasted, fried and pounded and could be chipped, dried and produced into yam flour. Yam is one of the major staple food in Nigeria and has potential for livestock feed and industrial starch production (Ayanwuyi et al, 2011). It is one of the principal tuber crops in the Nigeria economy, in terms of land under cultivation and in the volume and value of production (Bamire and Amujoyegbe, 2005). In Nigeria, yam is part of the religious heritage of several tribes and often plays a key role in religious ceremony (Sanusi and Salimonu, 2006). Worthy of note is the fact that many important cultural values are attached to yam, especially during wedding and other social ceremonies. In many farm communities in Nigeria and other West Africa countries, the size of the yam enterprise that one has is a reflection of the person’s social stature. Due to the importance attached to yam many communities celebrate the new yam festival annually (Izekor and Olumese, 2011). Traditionally, yam is a prestige crop that is view and received with high respect, prominently during special gatherings such as new yam festivals in rural communities of eastern, central and some parts of south west of Nigeria. In the humid tropical countries of West Africa yams are one of the most highly regarded food products and are closely integrated into the social, cultural, economic and religious aspects of life. The ritual, ceremony and superstition often surrounding yam cultivation and utilization in West Africa is a strong indication of the antiquity of use of this crop. Nigeria, the world's largest yam producer, considers it to be a "man's property" and traditional ceremonies still accompany yam production indicating the high status given to the plant (FAO, 2008).Nigeria is the largest producer of the crop, producing about 38.92 million metric tonnes annually (FAO, 2008). Yam production in Nigeria has more than tripled over the past 45 years from 6.7 million tonnes 1961 to 39.3 million in 2006 (FAO, 2007). This increase in output is attributed more to the large area planted with yam than increase in productivity (Nwosu and Okoli, 2010). There has, however, been a general decline in yam production in Nigeria over years. Madukwe et al. (2000), Agwu and Alu (2005) and International Institute of Tropical Agricultural [2009] reported that both area under yam cultivation and total yam output were declining. The decline in average yield per hectare has been more drastic, as it dropped from 14.9% in 1986-1990 to 2.5% in 1996-1999 (CBN, 2002, Agbaje et al, 2005 and FAO, 2007). This declining trend may not be unconnected with inefficiency of resource use and allocation (Nwosu and Okoli, 2010). The objectives of this study, therefore, are to determine the efficiency of yam producers under agroforestry enterprise and to also determine the socio-economic characteristics of the yam farmers as well as know the problems faced by farmers in yam production and finally to provide policy recommendations that will enhance yam production in the area.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was carried out in Sapoba Forest Area in Orhionmwon Local Government Area of Edo state. Edo state is located between latitude5°51N -7°33i N and longitudes 5°E-6°40iE. It shares common boundary with Ondo state in the west, Delta State in the east and Kogi state in the north. The vegetation of the state is moist rain forest in the south and derived savanna in the north. Sakpoba Forest Reserve lies between latitudes 4° - 4° 30’ and longitudes 6° - 6° 5’E. It is bounded on the south by Delta State, on the East by Urhonigbe Forest Reserve and on the West by Free Area, B.C. 30. It is located in Orhionmwon Local Government Area, about 30 kilometers South-East of Benin City. Some of the major villages located within and around the reserve are Ugo, Ikobi, Oben, Iguelaba and Amaladi in Area B.C 32/4, and Ugboko-Niro, Iguere, Idunmwowina, Evbarhue, Idu, Evbueka, Iguomokhua, Ona, Abe, Igbakele, Adeyanba, Evbuosa in Area B.C 29. Orhionmwon LGA has a population of about 182,717 according to 2006 census with a land area of 2.382km2 (NPC, 2006). The people of the area are farmers and traders. Crops grown in the area include: yam, cassava, maize, plantain, and cocoyam planted with some tress like Tectona grandis (teak) Gmelina arborea, Terminalia ivorenisis, Khaya ivorensis etc. The primary data were obtained using well structured questionnaire. A total of 60 farmers were purposively selected and interviewed among the villages namely: Ageka, Evbuosa, Ona, Iguomokhua and FRIN Camp in the LGA where agroforestry system is being practiced.

3. Data Description and Regression Model

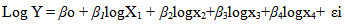

The data employed in this study consist of information on the socio-economic characteristics and production of a sample of 60 agroforestry farmers in Sapoba Forest Area of Orhionmwon Local Government Area of Edo State in Nigeria. The farmers produce various crops such as yam, plantain, maize, cassava, cocoyam, pepper melon etc. The inputs used in production include the land which is usually allocated to the farmers on annual basis, labour, capital (eg matchete, hoes etc) while the socioeconomic characteristics are the farmers’ level of formal education, years of farming, age. The production variables are also measured in value terms. Hired labour is measured in terms of man days. The average daily wage rate for agricultural farmers in the study area of N1400 is used. Education as a variable is measured in terms of years of formal education.The variables were used to construct an econometric model which consists of Cobb-Douglas functional form of the agroforestry farmers’ production function. The regression coefficients are all expected to have positive signs a priori. There are some problems inherent in Cobb-Douglas include constant elasticity of substitution and separability of each factor of production (Olarinde and Ajetomobi, 2000). However, its primary characteristics such ease of handling suitability for direct estimation of production elasticities and provision of good fit have informed its application in this study. From the Cobb-Douglas production function, the output elasticity of each production input was determined. This is equal to the value of the coefficient of the input. Also derived from the log-linear production function is the ratio of the marginal value product (MVP) of the various production inputs to the respective acquisition costs. This is done to examine the marginal returns to the agroforestry farm. This is an indication of efficiency in production. The Cobb-Douglas production function is very convenient for calculating the ratio especially when the variables are measured in value terms (Olarinde and Ajetomobi, 2000).

4. Model specification

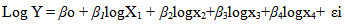

The empirical specification of the model is of the form shown below | (1) |

where Y= output βo = intercept of the function Xi = explanatory variable (i= 1-----n) εi = error termThe error term is assumed to be log normally distributed with mean 1 and contains among other things differences in efficiency between farms. The explicit form of the equation is as stated below  | (2) |

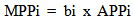

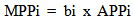

WhereY = yam output in kilograms Xi = land (farm size in hectares) X2 = hired labour (man days) X3 = value of capital used (hoes, matchete)X4 = quantity of seed yam εi = error term. β0 and βi are the constant and the regression coefficients respectivelyThe marginal physical product MPP was given as  | (3) |

where bi = elasticity of the various inputs. | (4) |

Where y is the mean of the output and x is the mean of the factor. Using the above specification and the output and input prices, the marginal value products (MVPs) and allocative efficiency index (AEI) were computed as follows: | (5) |

| (6) |

where Py and MFC are the unit prices of output and factor input respectively.The decision of whether a resource is used efficiently or not thus allocative efficient is basically on the value of AEI (Nimoh, et al., 2012). If AEI is equal to one (AEI=1) the factor input is efficiently utilized, hence the farmer is considered allocative efficient. The factor is over-utilized if AEI is less than one (AEI<1) and underutilized if AEI is greater than unity (AEI>1).

5. Results and Discussion

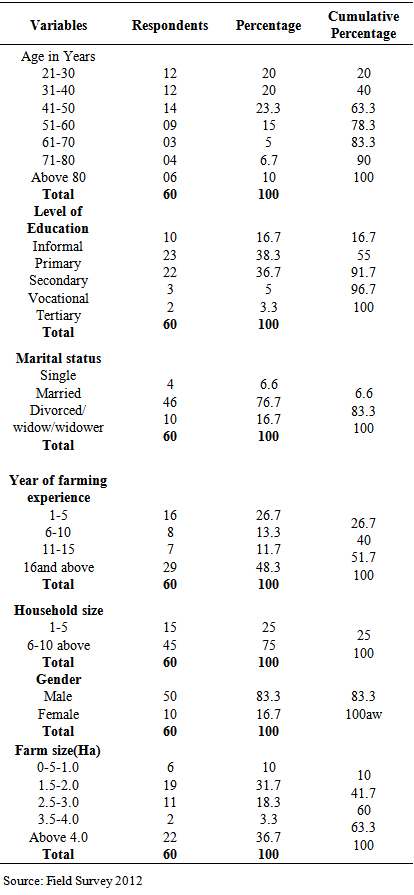

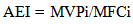

This section discusses the socio-economic characteristics of farmers which are known to influence resource productivity and returns on the farms. The summary of the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of farmers is presented in Table 1. The demographic and socio economic variables considered include age, gender of farmers, household size, farm size, years of farming, level of education and marital status. About 63.3% of the sampled farmers were between the age bracket 20 -50 years. This shows that majority of the farmers were middle aged and this implies that the farmers were still in their economic active age which could result in a positive effect on production. This result agrees with the findings of Alabi et al(2005) who observed that farmer’s age has great influence on maize production in Kaduna state with younger farmers producing more than the older ones plausibly because of their flexibility to new ideas and risk. Furthermore 83.3% of the sampled respondents had one form of formal education or the other. Onyenweaku et al (2005) and Idiong et al (2006) observed that formal education has positive influence on the acquisition and utilization of information on improved technology by the farmers as well as their innovativeness adoption of innovations. Some of the farmers (73.3%) have been farming for over 5 years. This means that they must have acquired good experience in agroforestry farming. Rahman et al (2003) indicated that the length of time in farming business can be linked to age. Age, access to capital and experiences in farming may explain the tendency to adopt innovation and new technology.Table 1. Socio economic characteristics of sampled farmers (N=60)

|

| |

|

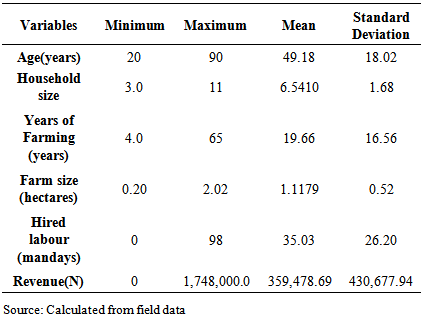

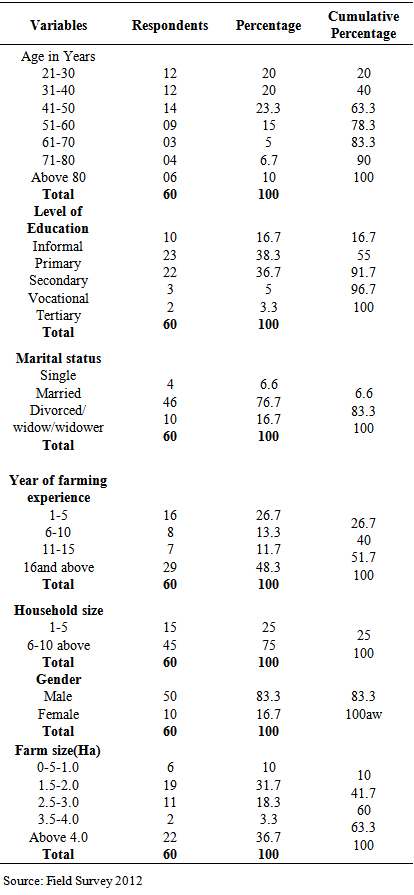

Table 2 revealed that the average age of the farmers was 49.2 years. About 83.3% of the farmers are married while 82% are male. An average farmer has a fairly large household of 6.5, cultivating about 1.12 hectares of land typifying a small scale holding with no one having more than one field suggesting that land fragmentation is not common in the forest reserve because farm lands are allocated to them by the government on year to year basis.Table 2. Summary of socioeconomic variables of respondents in Sapoba (N= 60)

|

| |

|

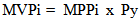

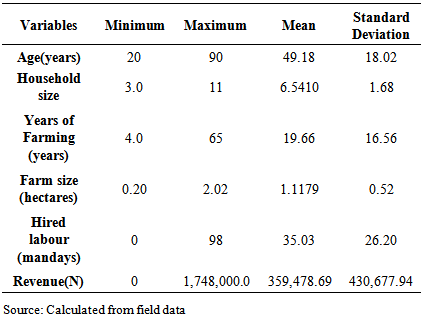

6. Results of the Regression Analysis

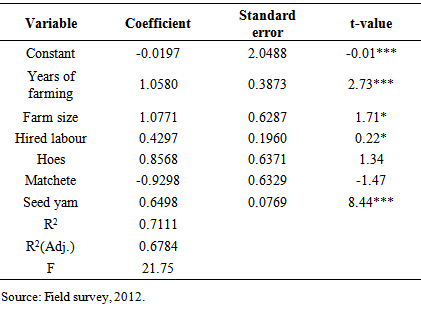

The results of the production function that was used to determine the nature of the relationship between the inputs and output in food production are shown in Table 3. The results in the table showed that the coefficient of multiple determinations R2 and adjusted R were 0.7111 and 0.6784, respectively. This implies that 67.84 percent variation in the output of yam in the area is accounted for by the specified independent variables. The F-ratio (21.75) which was significant at 1 per cent level of probability indicates the overall significance and fitness of the model.Table 3. Estimates of the Cobb-Douglas Production Function for yam in Sapoba forest area

|

| |

|

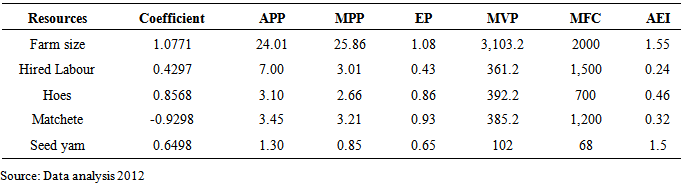

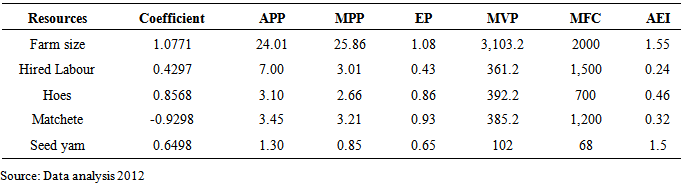

The results further showed that year of farming and seed yam (X4) were positive and significantly influenced yam production in the study area. Years of experience and seed yam were both significant at 1% level of probability. Farm size was positively significant at 10% and influenced yam production in the study area; it equally conformed to the expected sign of the study. The quality and, to some extent the, quantity of seed yam greatly influence yam output under agroforestry enterprise. In addition, the quality and fertility of the soil although not accounted for in our estimation has great effect on output especially since the soil under which the farmers were farming was an undisturbed high forest area. The elasticities of production (EP) with respect to the inputs were 1.0580, 1.0771, and 0.6498 for years of farming, farm size and seed yam, respectively. From the regression analysis, the sum of the elasticities of the various variables equal to 2.0836 indicating that the farmers were operating at the region of increasing returns to scales which suggests that they are still in stage one of the production process. Table 4 shows the estimates of allocative efficiency (AE) of inputs used by yam farmers in the study area. The allocative efficiency indices were 1.55, 0.24, 0.46, 0.32 and 1.5 for farm size, hired labour, hoe, matchete and seed yam respectively. The results showed that farmers were inefficient in their resource use. This finding corroborates the findings of Ike and Inoni (2006), Izekor and Olumese (2010), Shehu et al (2012) and Rueben and Barau (2012) that farmers were equally inefficient in resource use in their respective studies. The indices revealed that MVP exceeds the MFC in the cases of farm size and seed yam respectively. This implies those farm size and seed yam were underutilized in the production of yam in the study area. However, MVP was lesser than MFC in the case of hired labour, hoe and matchete suggesting that these inputs were over utilized in yam production in the study area. It is therefore expected that more yam would be produced if more hectares of land are cultivated and the quantity of seed yam is increased. Also, improved return on yam production can be recorded and achieved by reducing the over used resources in the area. Table 4. Estimated resource use efficiency

|

| |

|

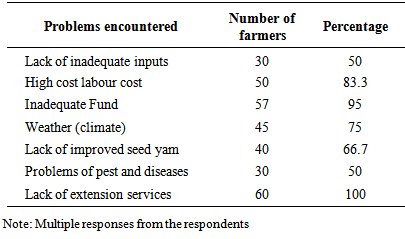

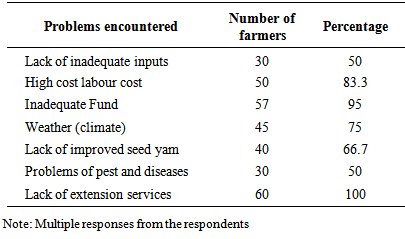

7. Constraints to Yam Production

The problems faced by farmers in yam production in the area include lack of adequate farm inputs (50%), high costs of hired labour (83.3%) and lack of improved seed yam (66.7%). This conforms with the findings of Rueben and Barau (2012) and Sanusi and Salimonu (2006) which listed the same variables as constraints to yam production in Taraba and Oyo States respectively. Others constraints faced by the farmers are lack of extension services (100%), inadequate fund (95%) and the problems of diseases and pests among others.Table 5. Constraints in Yam Production

|

| |

|

8. Conclusions

This study revealed that yam production in the study area is profitable. Among the variables that contribute to production include farm size, seed yam and labour. Analysis of the efficiency of yam production, however, revealed that farmers in the area are inefficient in the use of their resources hence there is the need to reduce the use of those resources that reinforce inefficiency especially hired labour to the level where the marginal value products of the resources equal their acquisition costs. Farmers can also increase their productivity and, by extension, profit by the use of improved seed yam as well as maximize the utilization of the farm land by increasing the number of seed yam planted per hectare.

References

| [1] | Agbaje, G.O.L, Ogunsunmi O.L, Oluokun J.A, Akimloju T.A. (2005). Survey of Yam Production system and impact of Government Policies in South Western of Nigeria. Journal of Food, Agriculture and Environment. 3(2): 222-229. |

| [2] | Agwu A.E. and Alu J.I (2005) Farmers’ perceived constraints to yam production in Benue state. Nigeria. Proceedings of the 39th Annual conference of the Agricultural Society of Nigeria, 2005; pp 347-50. |

| [3] | Alabi O. O, Adebayo O, Akinyemi O, Olumuyiwa SA, Adewuyi D(2005) Resource Productivity and Returns on Maize Production in Kauru Local Government Area of Kaduna State. Inter. J. Food and Agricultural Research. 2(1&2). |

| [4] | Ali, M (1996). Quantifying the Socio-economic determinants of Sustainable Crop Production: An Application to Wheat Cultivation in the Tarui of Nepal, Agricultural Economics. 14:45-60. |

| [5] | Ayanwuyi. E, Akinboye, A.O., and Oyetoro J.O. (2011) Yam Production in Orire Local Government Area of Oyo State, Nigeria: Farmers’ Perceived Constraints. World Journal of Young Researchers 2011(2)16-9. |

| [6] | Bamire A.S, Amujoyegbe B.J (2005). Economic analysis of Land improvement techniques in small-holder Yam-Based Production systems in the agro-Ecological Zones of South Western, Nigeria. Journal of Human Ecology. 18(1): 1-12. |

| [7] | CBN (Central Bank of Nigeria) 2002 Statistical Bulletin. 9 (20) 114-117. CBN, Abjua. |

| [8] | Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) (2008) FAOSTAT Statistical Division of the FAO of the United Nations, Rome Italy 2008. www.faostat.org. |

| [9] | FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) 2007. F.A. FAO STAT. Statistics Division of Food and Agriculture Organization …www. Faostat.org. accessed July 21, 2010. |

| [10] | Idiong C.I, Agom D.I, Ohen S.B (2006) Comparative Analysis of Technical Efficiency in Swamp and Upland Production Systems in Cross River State, Nigeria. In (Eds) Adepoju OA and Okunneye PB. Technology and Agricultural Developmemt in Nigeria. Proceedings of the 20th Annual National Conference of the Farm Management Association held in Jos 18th -21 September 2006. Pp 30- 39. |

| [11] | IITA (International Institute for Tropical Agriculture) 2009 http.//www.iita.org. accessed July 21, 2010. |

| [12] | Ike P.C and Inoni O.E (2006) Determinants of yam production and economic efficiency among small-scale farmers in south-eastern Nigeria. Journal of Central European Agriculture. 7. (2.): 337-342. |

| [13] | Iwueke C.C. Mbata E.N Okereke H.E (2003) Rapid Multiplication of seed yam by minisett technique. National Root Crops Research Institute, Umudike, Abia State, Nigeria, Advisory Bulletin 2003 No 9 pp5. |

| [14] | Izekor O. B. and Olumese M. I. (2011) Determinants of yam production and profitability in. |

| [15] | Edo State, Nigeria. African Journal of General Agriculture. 6(4). |

| [16] | Madukwe MC, Ayichi D, Okoli EC (2000). Issues in yam minisett technology transfer to farmers in Southwestern Nigeria. African Technology policy studies working paper No. 4, Nairobi, Kenya. 2000; 52. |

| [17] | Nwosu, C. S and V. B. N. Okoli (2010). Economic Analysis of Resource use by Wase Yam Farmers in Owerri Agricultural zone of Imo State, Nigeria in proceedings of 44th Annual Conference of Agricultural Society of Nigeria held in Ladoke Akintola University 18-22 October, 2010. |

| [18] | Nimoh,F, Tham-Agyekum E.K and Nyarko, P.K.(2012)Resource Use Efficiency in Rice Production: the Case of Kpong Irrigation Project in the Dangume West District of Ghana. International of Journal Agriculture and Forestry 2(1):35-40. |

| [19] | Olarinde, L.O. and Ajetomobi, J.O. (2000) Economic Efficiency of Homestead Fish Farmers in Ejigbo Area of Osun State. Nigerian Agricultural Development Studies 1 (2):20-26. |

| [20] | Onyeweaku, C. E, Igwe K.C, Mbanasor J.A (2005) Application of a Stochastic Frontier Production Function to a Measurement of Technical Efficiency in Yam Production in Nasarawa State, Nigeria, Journal of Sustainable Tropical Agricultural Research.13:20-35. |

| [21] | Rahman, S.A, Mali, J.N (2002) Factors Affecting Adoption of ICSVIII and ICSV 400 Sorghum Varieties in Guinea and Sudan Savanna of Nigeria. Journal of Crop Research, Agroforestry and Environment, 1(1):21. |

| [22] | Reuben, J and Barau, A.D (2012) Resource Use Efficiency in Yam Production in Taraba State Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Science. 3 (2): 71-77. |

| [23] | Sanusi W.A. and Salimonu K.K (2006) Food Security among Households: Evidence from Yam Production in Oyo state, Nigeria. Agricultural Journal 1(4):249-253. |

| [24] | Shehu J.F, Iyortyer, I.T Mshelia S.I. and Jongur A.A.U (2010) Determinants of yam production and technical efficiency among farmers in Benue State, Nigeria. Journal of Social Science 24 (2): 143-148. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML