-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2014; 4(4): 325-337

doi:10.5923/j.ijaf.20140404.10

Analysis of Vegetable Seed Systems and Implications for Vegetable Development in the Humid Tropics of Ethiopia

Amsalu Ayana1, Victor Afari-Sefa2, Bezabih Emana1, Fekadu F. Dinssa2, Tesfaye Balemi1, Milkessa Temesgen1

1HEDBEZ Business & Consultancy PLC, P. O. Box 15805, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

2AVRDC - The World Vegetable Center, Eastern and Southern Africa, P. O. Box 10 Duluti, Arusha, Tanzania

Correspondence to: Victor Afari-Sefa, AVRDC - The World Vegetable Center, Eastern and Southern Africa, P. O. Box 10 Duluti, Arusha, Tanzania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

In Ethiopia, vegetables are important for economic, nutrition, health, smallholder farming system sustainability and attract foreign direct investment. However, advancement of the sub-sector is constrained by spatial and time gaps in seed supply systems. Based on a field survey, vegetable seed supply and distribution systems and associated policy and legal framework governing its development were assessed. Results show that different vegetable seeds types are produced and distributed through informal, semi-formal and formal channels. - Individual entrepreneurs dominate the informal system while private local and multi-national seed companies are involved in the formal systems. Preference for specific vegetables varieties is location specific. Recent enabling legal and policy frameworks have boosted investment in the sub-sector thereby increasing demand for vegetables seeds both in quantity and value. Lack of quality seeds and technological know-how remain critical bottlenecks, calling for need to strengthen quality control frameworks, extension services and linkages among supply chain actors.

Keywords: Seed systems, Vegetable seed, Vegetable breeding, Dietary diversity, Micronutrient, Malnutrition, Ethiopia

Cite this paper: Amsalu Ayana, Victor Afari-Sefa, Bezabih Emana, Fekadu F. Dinssa, Tesfaye Balemi, Milkessa Temesgen, Analysis of Vegetable Seed Systems and Implications for Vegetable Development in the Humid Tropics of Ethiopia, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 4 No. 4, 2014, pp. 325-337. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20140404.10.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Vegetable production is an important economic activity in Ethiopia. The production system ranges from home gardening, smallholder farming to commercial farms owned both by public parastatal and private enterprises (Zelleke and Gebremariam, 1991; Aklilu, 2000). In the context of this paper, vegetables are defined in culinary terms to include vegetables “proper”, that have fruit and leafy herbaceous parts eaten raw or cooked (i.e., lettuce, head cabbage, Ethiopian cabbage/kale, tomatoes, green and red peppers, Swiss chard, celery, green beans, etc.), root and tubers which include beetroot, carrot, potatoes, sweet potatoes, taro/ godere and bulb crops (onion, garlic, shallot) (CSA, 2013)]. Indeed, Ethiopia is endowed with diverse agro-ecologies suitable for the production of different categories of vegetables. Tropical, sub-tropical and temperate vegetables are produced in the lowlands (<1500 meters above sea level), midlands (1500-2200 masl), and highlands (>2200 masl), respectively (FAO, 1984; EHDA, 2011; EHDA, 2012). The development of the vegetable sub-sector is one of the priority areas in the agricultural development strategy of Ethiopia (Ethiopian Investment Agency, 2008; 2012). Such emphasis emanates from recognizing the importance of vegetable crops for food security (e.g., root and tubers, and Enset ventricosum), and for human nutrition and health (source of vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, dietary fiber and for having anti-carcinogenic properties). Moreover, vegetables serve as raw material for agro-industries (tomato pastecapsicum and oleoresin extraction from chili peppers). Their importance as a source of employment and foreign currency earner is increasing. Vegetables serve as suitable crops for farming systems diversification and land intensification, particularly with recent increases in the establishment of small and medium scale irrigation schemes in the country (Demissie et al., 2009; Baredo, 2012).The area under vegetables increased from 350,600 ha with production of 2.36 million tons in 2010 to 396,510 ha with production of 4.48 million tons in 2013 for smallholder farmers (CSA, 2010; 2011; 2012; 2013). This implies that the area cultivated to vegetables increased by 13% while the production increased by 103%, between 2010 and 2013. The area under vegetable production and the quantity produced by medium and large scale commercial state and private farms also showed an increasing trend during the reference period. Similarly, export of vegetables increased from 37,210 tons valued at USD163.86 million in 2003 to 220,210 tons valued at USD 437.5 million in 2013(Ethiopian Revenue and Customs Authority, 2013), representing 709% increase in export volume and 167% in revenue.A number of institutions support the development of the sub-sector. These include the Ethiopian Horticulture Development Corporation (EHDC), which has been carrying out production and marketing activities of horticultural crops since its establishment in the 1980's (Yohannes, 1989). The Ethiopian Fruit and Vegetables Marketing Enterprise (ETFRUIT) is also a parastatal trading organization established in 1980 under the EHDC to coordinate domestic and export trade of fresh fruits, vegetables, flowers, and processed horticultural products while federal and regional research institutions have the mandate to develop and release improved varieties along with recommendations on good agricultural production practices.There has been a substantive, long-term underinvestment in research and development of the horticultural sector in Africa with particular reference to those traditional crops, which are naturally high in nutritious vitamins and minerals (Afari-Sefa et al., 2012). Despite the multifaceted importance of vegetables in Ethiopia and the high priority given by policy makers for the development of the sub-sector, vegetable seed supply and distribution system is generally weak. There is limited access to information in terms of availability of varieties, seed source and quality as well as price (Tabor and Yesuf, 2012). The bulk of existing cultivated seeds are imported, often - that are not adapted to the local agro-climate. For certain vegetable crops, the informal seed system is the major source of seeds, which is triggered by poorly developed vegetable seed system in the country. To narrow this spatial, time information gaps in the vegetable seed systems while helping to devise a farming systems oriented research for development approach, a study was undertaken within the context of the Humidtropics Program. The Humidtropics Program is a CGIAR Research Program on integrated agricultural systems for the Humid tropics. The program is being implemented in several countries across the globe including Ethiopia. The objectives of the study are to: (i) assess the vegetable seed supply and distribution systems, (ii) identify opportunities and constraints affecting target communities and beneficiaries of the Humidtropics agro-climatic zones, and (iii) assess the influence of national policy and legal framework governing vegetable seed development, production and supply chain in the country.

2. Methods

2.1. The Study Sites

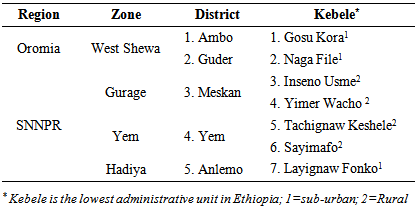

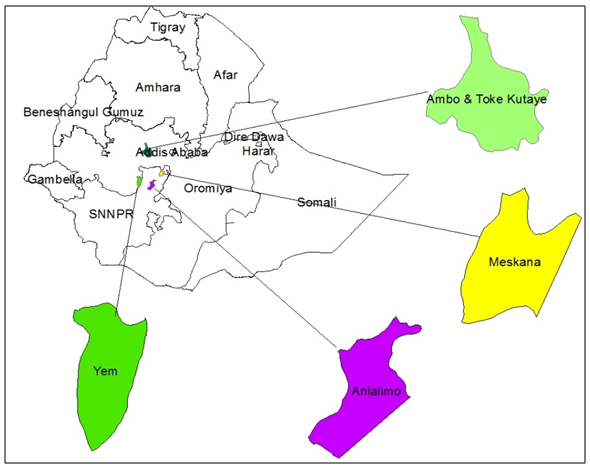

- The study was conducted in four major vegetable producing zones in Ethiopia. These include: West Shewa located in Oromia National Regional State, Gurage and Hadiya and Yem (special district) zones located in the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR), respectively (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the list of districts (district is locally called woreda) and kebeles (farmers associations which are the lowest institutionalized administrative unit) in each of the selected zones. In total, 7 kebeles in 5 districts were included. The districts and kebeles were selected in a participatory manner through discussions with zonal and district vegetable experts, purely based on the potential they have for vegetable production. Based on local knowledge and information, districts and kebeles that are representative are sampled so as to shade light on vegetable production potential of the study areas and address the objectives of the study.

| Figure 1. Map of the study sites (adapted by the study team) |

|

2.2. Study Approach and Data Sources

- A field study survey involving a combination of qualitative and quantitative survey methods was undertaken from October to December 2013 to elicit data from representatives of various vegetable value chain actors and support service providers. Notably, horticultural experts from zonal and district bureaus of agriculture, farmers, traders, and representatives of farmers’ cooperative unions provided the necessary data. Data were collected through Key Informants Interview (KII), Focus Group Discussion (FGD) and field survey. Horticulture experts at zone, district and Farmers' Training Centers were interviewed as key informants on vegetable production and marketing. In total, 12 Agricultural Development Agents (ADA, 42% female) and 12 horticulture experts (8% female) were interviewed using a checklist developed for the purpose of eliciting data. In each of the selected districts, 2 FGDs were conducted. In each village of the selected districts, one-women and one men-group participated in separate FGD sessions. In total, 150 persons (41% female) provided necessary data for this study. All discussions were guided by checklists prepared for the purpose of the study. The data collected included type of vegetables produced, ranking of vegetables in order of importance, seed supply, vegetable seed production and marketing, and vegetable seeds handling practices of agencies. Information with regard to challenges and opportunities for improving vegetables seed supply was explored to suggest use of quality vegetable seeds on a sustainable base.The primary data was augmented with secondary data collected from various reports that were available from zonal and district level agriculture offices of the study areas. In addition, desk reviews were made using relevant published materials and websites of national organizations such as Ministry of Agriculture (MOA), Central Statistical Agency (CSA), EHDA, Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research and Ethiopian Revenue and Customs Agency. Quantitative data gathered from secondary sources were presented in the results by referring to the sources, while others were used as supportive literature.Data obtained from various sources were triangulated and checked for consistency before analysis. Primary data collected were coded and entered into Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheet and subsequently into SPSS Version 15 software. Descriptive statistics tools were used to analyze and present the data.

3. Results and Discussion

- This section is divided into two major categories: (i) vegetables seeds supply and demand which presents the formal and informal vegetable seed supply and distribution systems and the demand for seed; and (ii) policy and regulatory frameworks affecting vegetable seeds development, production, distribution and support services in Ethiopia.

3.1. Vegetable Seeds Supply and Demand

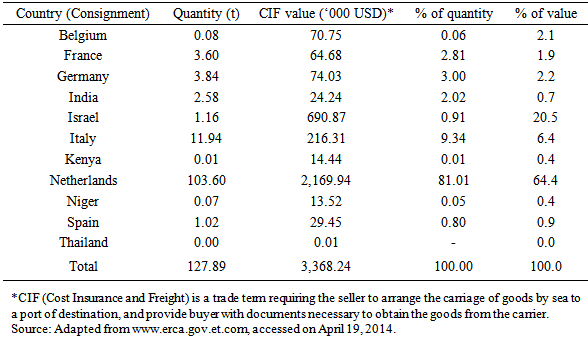

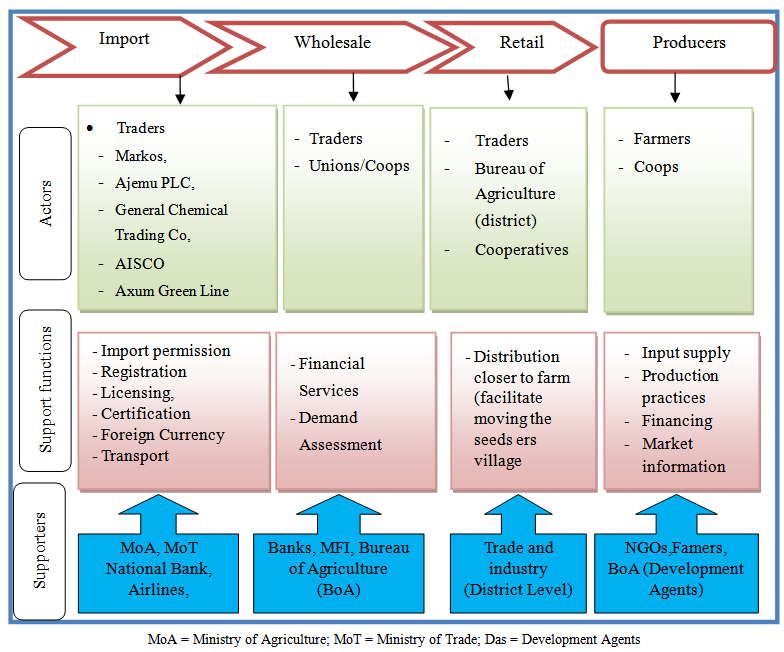

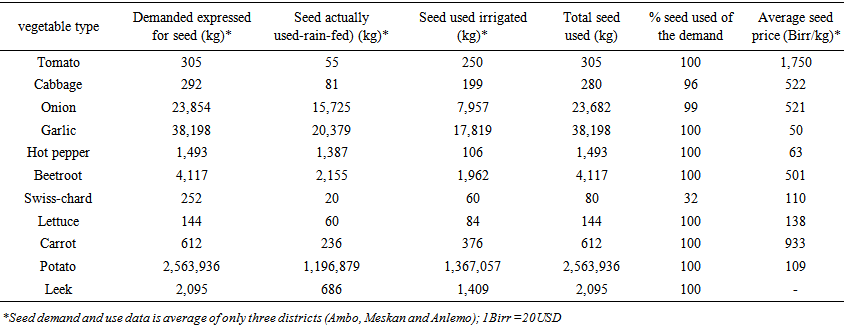

- Production, marketing and distributionTo a large extent, vegetable seed demand in Ethiopia is met through commercial seed imports mainly by private seed importers and parastatal enterprises such as ETFruit and AISCO. In 2012 alone, a total of 128 tons of different vegetable seeds was imported (Table 2). This represents a more than 50% increase in volume compared to 84 tons imported in 2010 and 276% increase relative to the imported quantity in 2004 (Hassena and Desalegn, 2011; Desalegn, 2012). The increase in import of vegetable seed is attributed to expansion of irrigated vegetable production both for local consumption and export. This implies that there is a substantial demand for vegetable seeds and increase in vegetable production in Ethiopia within the reference period. As can be observed from Table 2, the bulk of the imported seed is from the Netherlands (more than 80% of the quantity and 64% of the value), followed by Italy, Germany and France. Vegetable seeds imported from Israel accounts for 20% of the value.

|

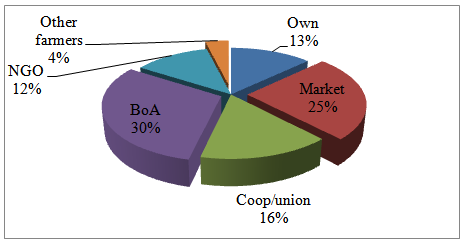

| Figure 2. Proportion of tomato seed supplied by different sources in the study areas |

| Figure 3. Seed supply chain for imported vegetable varieties, 2013 |

|

| Table 4. Vegetable seed demand, seed used and average price in 2012 cropping season |

3.2. Policies and Regulatory Frameworks

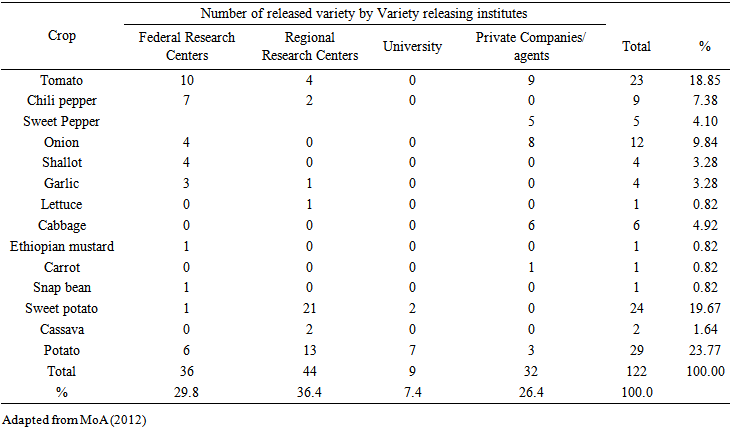

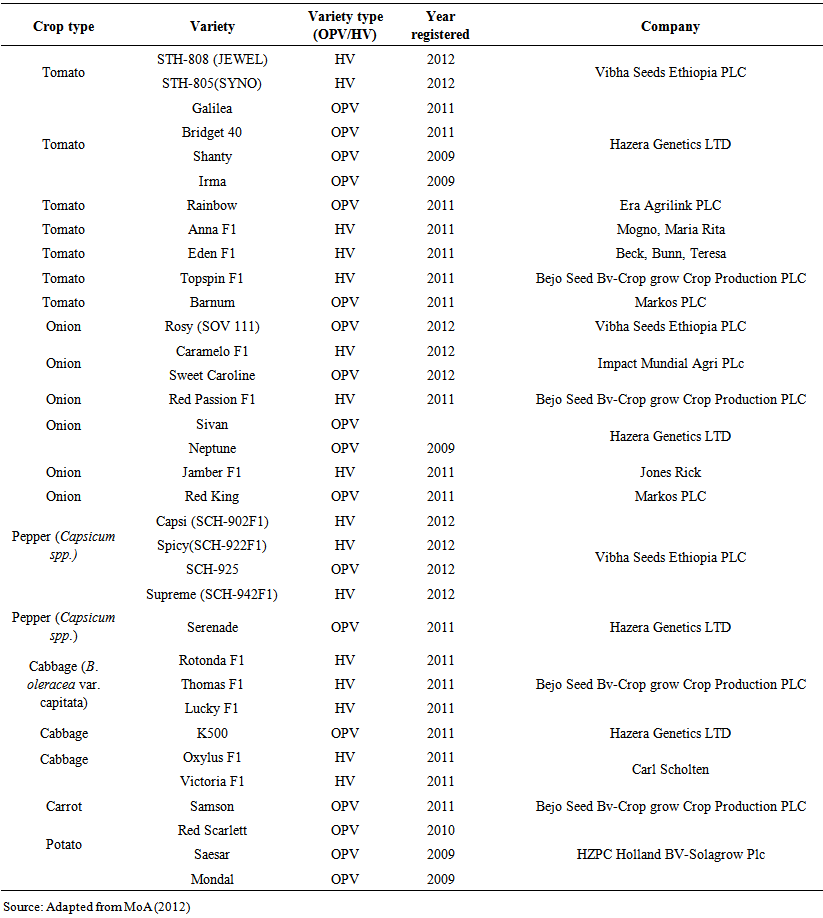

- Variety developmentEthiopia has a well-established agricultural research programme, operating at federal as well as national regional states (www.eiar.gove.et). Horticulture (including vegetables, fruits and root and tuber crops) is one of the research programmes in the Ethiopian Agricultural Research System. However, the resources (budget and research staff) allocated to horticultural researches are not adequate and often much less than the resource allocated to major field crops such as cereals, pulses and oilseeds. This indicates that less emphasis is given to the sector in the research system. Even then, potato, tomato, pepper, onion, and sweet potato, in that order, are among the crops for which major emphasis is given in terms of research thrust. Only vegetables such as shallot, garlic, and paprika (Capsicum annuum) are considered to a limited extent. For other vegetables like head cabbage, carrot, onion, beet root, lettuce, cauliflower, spinach, and Swiss chard, packed seeds are imported by private companies mainly from European countries such as Denmark and the Netherlands. In addition to the fact that they are mostly not adapted to the local agro-climate, the generational identity (hybrid or open-pollinated) of imported seeds is seldom known. In Ethiopia, the Melkasa Agricultural Research Center, which is located 117 km southeast of Addis Ababa in the Rift Valley, is the main vegetable (tomato, pepper, onion, snap bean) research center. Debre Zeit Agricultural Research Center is working on garlic and shallot. Regional research centers (Bako, Adet, Areka, Sinana, and Hawassa), federal research center (Holeta), and Haramaya University focus more on root and tuber crops such as potato, sweet potato, enset, taro, yam, and cassava (MoA, 2012).Principally, vegetable breeding programme in the majority of sub-Saharan African countries is practically nonexistent with capacity in the public sector having been severely reduced historically through lack of funding and privatization (Afari-Sefa et al., 2012). The situation in Ethiopia is not much different with the Ethiopian Agricultural Research System (NARS) having a low research capacity and capability in the sector as a result of which vegetable seed supply is predominately dependent on imported seed (Tabor and Yesuf, 2012). As such the NARS neither has enough capacity for germplasm and variety development nor connected to other external sources and/or resources for acquiring adapted seeds of cool season vegetable crops such as kale, Ethiopian mustard, pumpkin, carrot, cabbage, beet root, lettuce, and Swiss chard (Mengistu et al., 2003). This implies a low national research capacity for breeding climate resilient vegetable varieties to cope with climate change stressors and their adaptation.Variety release and registrationAs it is true with many other sub-Saharan African countries such as Tanzania and Mali, Ethiopia does not have a separate variety release criteria/procedure for vegetable crops. Upon satisfying the requirements for Value for Cultivation and Use (VCU) test, crop varieties (including vegetable varieties) are released and registered by the National Variety Release Committee (NVRC) under the patronage of the Directorate of Animal and Plant Health Regulatory Services (APHRS) of the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA, 2012). So far there are no DUS (Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability) testing requirements for variety release and registration in the country, although MoA is in the process of introducing DUS testing as indicated in the recently revised seed law. Thus, to-date variety release is based on VCU test. The NVRC is a standing committee under the MoAentrusted which has been exercising its responsibility of variety release and registration since 1982 (Gebeyehu et al., 2001). Often presided over by a breeder, members of NVRC are of diverse disciplines (breeding, crop protection, agricultural extension, socio-economics, agronomy, and food science) and constituted from research institutes, universities and MoA. The NVRC is assisted by ad hoc Technical Committees (TCs) for different crops to evaluate verification plots and performance trial data (of a minimum of 3 locations x 2 seasons) of candidate crop varieties and provide recommendations to NVRC whether the variety can be released or rejected. Members of the TCs are also mainly crop specialists consisting of breeder, agricultural extension specialist, crop protection (pathologist or entomologist), agronomist and food scientist. The NVRC deliberates twice per year to review applications for variety release and registration. The APHRS at MoA publishes annually the Crop Variety Register, in which newly released and registered varieties are described and list of previously released and registered crop varieties are included (MoA, 2012). Table 5 shows summary of released vegetable, root and tuber crops up to 2012 by category of releasing institutes, i.e., federal research centers, regional research centers, universities and private seed companies/agents.

| Table 5. Summary of number of released vegetable, root and tuber crops in Ethiopia |

| Table 6. Commercial vegetable and seed potato varieties (open pollinated – OPV, and hybrid – HV) registered in Ethiopia |

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

- There is a general increasing trend for development of the horticultural sub-sector partly due to increasing demand emanating from increasing population, urbanization, increased awareness of the nutritional and health importance of horticultural crops like vegetables and fruits. This has triggered increased demand for good quality seed. The demand for agro-processing and export of vegetables is also quite substantial. Ethiopia has diverse agro-ecologies for production of cool season vegetables like cabbage, onion, carrot, beetroot, Swiss chard, kale and Ethiopian mustard and warm season vegetables like tomato, chili and sweet pepper as well as green beans. The high demand for horticultural products, availability of suitable agro-ecology, and increasing irrigation schemes development focusing on vegetable production, have resulted in increased demand for quality seeds of improved varieties of various vegetable crops so as to serve further boost in local production, albeit with increased investment.Increasing number of international and local private agents are introducing, getting tested and registered commercial vegetable varieties in Ethiopia, which, in turn, is increasing the chance of boosting vegetable production using high yielding improved varieties, seeds of which can easily be imported and/or produced in the country. Increasing number of agro-companies are importing and distributing commercial vegetable seeds in the country. Since there are a number of stockiest in different parts of the country, the imported seed is easily distributed to the major vegetable producing areas and respond easily to the vegetable seed demand. However, good quality seed is still lacking due different factors: limited policy implementation capacity (e.g., facilities such as laboratory, logistics, and budget) and capability (knowledge and skill gap). Similarly, there is limited capacity of public sector vegetable breeding program to develop and release seeds that are more adapted to specific agro-ecologies in the country as well as for effective vegetable seed production and distribution, extension services and weak linkages and integration among value chain actors. A number of opportunities and constraints influenced the development of vegetable seed system and vegetable production and marketing in Ethiopia. Fully exploiting the opportunities may result in minimizing the underlying challenges. The findings of the study have the following implications to enhance the supply of quality vegetable seed and substantially contribute to increased productivity.A similar scoping study has assessed opportunities and constraints for future economic development of sustainable vegetable seed businesses in eastern and southern Africa (Lenné et al., 2005). The results indicated that domestic vegetable production is limited by poor access to improved varieties, quality seed and technical assistance, among others. On the basis of the analysis from the study, the following recommendations are proffered. There is an urgent collective need by the Ethiopian government, development agents and the private sector to: i. Strengthen the vegetable seed quality control and assurance system to ensure inspection and certification of vegetable seeds. This calls for developing the capacity and capability of the seed regulatory systems of the MoA and regional bureaus of agriculture, including seed laboratories and strengthen the quarantine facilities. ii. Increase research capacity and capability for germplasm and variety development of major vegetable crops. Neglected traditional vegetables such as kale and Ethiopian mustard need to be given due attention in terms of germplasm and variety development and seed production. iii. Enhance both public and private engagement in vegetable technology generation, seed multiplication, marketing and distribution in order to fully exploit the climatic and agro-ecological factors suitable for vegetable production in the country and meet the export demand for fresh vegetables. There is special need to develop vegetable sector specific guidelines for the development of the seed supply chain in Ethiopia. This calls for transformation of the seed supply system from informal to more formal type through system establishment and capacity development.iv. Promote public-private partnership among NARS, international vegetable research and development centers, and commercial vegetable breeding and seed companies in order to access germplasm and commercial varieties for such important vegetables like kale, pumpkin, cabbage, cauliflower, carrot, beetroot and Swiss chard.v. Develop clear regulation and directives for registration of commercial varieties by private investors so that more number of varieties of different vegetable crops can be introduced and produced in the country and prepare clear guidelines for the importation and distribution of quality vegetable seed to meet demand adequately.vi. Increase public and private sector investment in irrigated vegetable production to increase the supply of vegetable, which in turn will increase the demand for vegetable seed.An overarching recommendation and critical determinant of success is the need to develop well-coordinated and integrated value chains for key vegetables in the country, where seed delivery is an integral component.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The financial support of the Integrated Agricultural Systems of the Humid tropics program (Humidtropics), a CGIAR Research Program for this research study is gratefully acknowledged.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML