Dadson Awunyo-Vitor 1, Ramatu M. Al-Hassan 2

1Department of Agricultural Economics, Agribusiness and Extension, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi

2Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness, University of Ghana, Legon

Correspondence to: Dadson Awunyo-Vitor , Department of Agricultural Economics, Agribusiness and Extension, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

This paper analyses factors influencing maize farmers’ demand for financial services provided by formal financial institutions in Ghana. The services include savings, loans, and money transfers. A multi-stage sampling technique was used to sample 595 maize farmers in seven districts in Ashanti and Brong Ahafo Regions of Ghana. A multinomial logit model is developed to identify and quantify the effects of factors that explain farmers’ use of financial services from formal financial institutions. It is found that education, asset endowment, engagement in off farm income generating activities, farm size, and level of maize commercialisation are the most important factors that drive farmers’ demand for at least one of these services compared with the use of none of them. This implies that maize farmers who are relatively better off in terms of earning capacity make use of formal financial services. In the short term, policies aimed at improving incomes and farm size of farmers, are needed to improve farmers’ access to formal financial services. Furthermore improving access to secondary sources of income for the farmers in the long term should form part of a comprehensive policy aimed at improving farmers’ access to financial services.

Keywords:

Demand drivers, Formal financial services, Ghana, Maize farmers, Multinomial logit

Cite this paper: Dadson Awunyo-Vitor , Ramatu M. Al-Hassan , Drivers of Demand for Formal Financial Services by Farmers in Ghana, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 4 No. 4, 2014, pp. 261-268. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20140404.01.

1. Introduction

In developing countries, the majority of the population, particularly low-income earning people, do not have access to loans, savings and insurance products offered by formal institutions (Honohan, 2006). Access to formal financial services can increase households’ ability to accumulate assets, upgrade their income generating activities as well as promote their capability to adequately deal with risks (World Bank, 2008). Households demand savings products and remittances and not only credit (Asiedu-Mante, 2005). However due to supply-side constraints, much of the literature concentrates on how to increase access to credit for more people in developing countries (Gallardo, 2006; Ledger wood and White, 2006). Demand for financial services has been considered in the context of consumer behaviour. It has been observed that a farmer’s decision on whether to use a financial service or not depends on their economic endowment and demographic and household characteristics. Khalid (2003) examined access to formal and quasi-formal credit by smallholder farmers and artisanal fishermen in Zanzibar using household survey data. He defined access in terms of use and analysed the data using alogit model. His study showed that application for credit facilities is linked to holding a saving or deposit account with a positive balance. The effect of household characteristics on demand for formal financial services has also been studied by Giné and Yang (2009). They used a randomized field experiment, with 800 maize and groundnut farmers in Malawi, to investigate whether the provision of insurance against a major source of production risk induces farmers to take out loans to adopt a new crop technology. The study revealed that insured loan take-up was positively correlated with farmer education, income, and wealth.A survey undertaken by Basu et al. (2004), has shown that small rural entrepreneurs seeking finance for their projects constitute a relatively smaller subset of the population of poor households than the segment interested in accessing deposit services. They assert that rural households place more value on the availability of secure savings than credit facilities due to the following reasons: Firstly, savings helps the poor to smoothen consumption expenditures and provides a cushion against income fluctuations caused by droughts, floods and bushfires for example. Secondly, savings may be used to pay for inputs needed at the start of the production season. Thirdly, savings provide a convenient way of setting aside money for future events such as funerals, weddings and payment of children’s school fees. Asiedu-Mante (2005) observed that poor people need a variety of financial services and not just loans, although it is most often assumed that the poor need only credit. He also asserted that demand for financial services is interrelated as most of the formal financial institutions use savings as a pre-requisite for a loan application as well as for access to other services. For example, rural banks discriminate between clients and non-clients in terms of commission on domestic money transfer services. Steiner (2008) identified factors influencing demand for formal financial services (savings, credit and insurance) in rural Ghana with multinomial logit model using data from 351 clients of two rural banks. Her results revealed that asset endowments of the household, type of economic activities and financial literacy are the most important factors in explaining the use of at least one of these services compared with use of none of them. Most of the studies on access to formal financial services in Ghana have concentrated on credit; furthermore the studies are skewed to banks only (Ekumah and Essel, 2001; ISSER, 2008). Though Steiner (2008) analysed factors influencing household decision to use formal savings, credit and insurance services in Ghana, she used only rural banks and did not consider money transfer services. Most providers of formal financial services require prospective borrowers to have savings accounts with them. Therefore, to assess how to improve access to formal financial services it is important to evaluate farmers’ demand for financial services jointly. This provides answers to the following research questions: (i) who are the suppliers of formal financial services in the study area and what services are used by the farmers? (ii) Under what terms and conditions are these services available to farmers? (iii) What factors influence demand for these services. In this study, demand is understood as satisfied demand (use of financial services from formal financial institutions). Formal financial institution is broadly defined to include savings and loans companies and credit unions in accordance with the passage of the Lenders and Borrowers Bill 2008 (Act 773).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Procedure

Multistage sampling was conducted in two select regions, 7 districts and included 595 farmers for the study. Selection of the regions and districts was guided by the level of agricultural activities and the level of maize production using official statistics from the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) (2009). Data on demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of farmers and their households, household assets and the farmers’ attitudes towards formal financial services were collected from a sample of 595 maize farmers.

2.2. Analytical Procedure

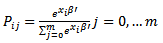

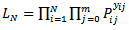

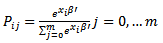

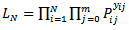

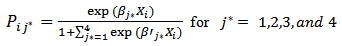

Descriptive statistics is used to describe all formal financial institution operating in the study area, the services they provide and conditions for accessing these services. In addition a multinomial logit model is estimated to explain demand for formal financial services following Steiner (2008). The formal institutions in the study area offer savings, credit, and money transfer services to farmers. The farmers then have eight alternative choices to make with regards to the use of financial services. However, within our data set only 5 respondents used savings and credit, and 6 respondents used savings and money transfer while none of the respondents used credit and money transfer services. Therefore only the following alternative choices were considered in our model. 0= None of the financial services1= Credit2= Savings3= Money transfer services4= All three services.In selecting any of the options above the respondent considers the costs and benefits associated with the use of these services based on how it would lead to maximization of their utilities. The net benefits to farmer i for using alternative j by i is given as  and

and  modelled as:

modelled as: | (1) |

Where  denotes the vector of observations on the variable X for farmer i, and

denotes the vector of observations on the variable X for farmer i, and  and e are parameters to be estimated and the error term respectively. In equation 1,

and e are parameters to be estimated and the error term respectively. In equation 1,  is not observed; instead we observe the choice made by the respondents. Each respondent will fall into the

is not observed; instead we observe the choice made by the respondents. Each respondent will fall into the  category, for

category, for  with some probability.Let

with some probability.Let  be the probabilities associated with these five possible choices available to the farmers. The probability

be the probabilities associated with these five possible choices available to the farmers. The probability  of respondents using a particular alterative is conceptualised to depend on variable

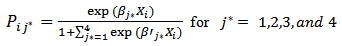

of respondents using a particular alterative is conceptualised to depend on variable  and with e assuming a logistic distribution. The probability of a respondent i using a particular option j can be presented in a multinomial logit form as:

and with e assuming a logistic distribution. The probability of a respondent i using a particular option j can be presented in a multinomial logit form as:  | (2) |

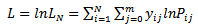

Where  the likelihood function for the multinomial logit model can be written as:

the likelihood function for the multinomial logit model can be written as: | (3) |

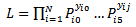

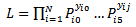

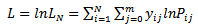

Equation (3) gives multinomial density function for one observation while equation 4 gives the likelihood function for a sample of N independent observations with j alternative option is presented as:  | (4) |

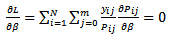

The log likelihood function can be re-formulated as: | (5) |

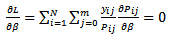

Where  is a function of parameters

is a function of parameters  and regressors defined in equation 2, with first order condition for the MLE of

and regressors defined in equation 2, with first order condition for the MLE of  as:

as: | (6) |

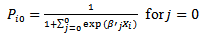

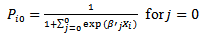

The probability of a farmer selecting the first option (base category)  has been normalised to zero since all the probabilities must sum up to 1 (Maddala, 1999; Green, 2000). Therefore, out of the five choices, only four distinct sets of parameters are identified and estimated. The probability of the respondent using the base category can be formulated as:

has been normalised to zero since all the probabilities must sum up to 1 (Maddala, 1999; Green, 2000). Therefore, out of the five choices, only four distinct sets of parameters are identified and estimated. The probability of the respondent using the base category can be formulated as:  | (7) |

and the probability of the respondent using any of the alternatives instead of the base category is given by  | (8) |

The odds ratio ( ) measures the probability that an individual would use a financial service relative to the base category of not using any financial services. The estimated coefficient for each choice therefore reflects the effect of

) measures the probability that an individual would use a financial service relative to the base category of not using any financial services. The estimated coefficient for each choice therefore reflects the effect of  on the likelihood of the respondent’s demand for that financial service(s) relative to the reference option. In this study, non-use of any of the financial services is taken as the base category against which the rest of the alternatives are compared.

on the likelihood of the respondent’s demand for that financial service(s) relative to the reference option. In this study, non-use of any of the financial services is taken as the base category against which the rest of the alternatives are compared.

2.3. Choice of Variables and Their Description

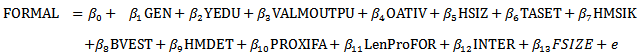

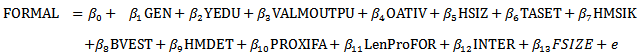

The selection of the independent variables is informed by the literature including studies such as Bendig et al. (2009) and Rahji and Fakayode (2009). The likelihood of use of saving, credit and money transfer services is assumed to be influenced by gender [GEN]. Female farmers often tend to be poorer than male farmers. World Bank (2005) and Johnson (2006) indicate that the female gender in the individual, household, wider community and national context are affected by financial, economic, cultural, political and legal obstacles which affect their demand for financial services. Gender is specified as a dummy variable which takes the value of 1 if the respondent is male and 0 otherwise. It is hypothesised that male farmers are more likely to use formal financial services compared to female farmers. Respondents who have attained higher educational levels are expected to have more exposure to the financial institution’s policies regarding use of financial services. The higher the educational level [YEDU] the more likely the farmer would be to be able to understand the needs of financial institution in terms of requirement for access to their services. Therefore, it is hypothesized that education would have a positive relationship with demand for financial services.The value of maize harvested [VALMOUTPU] is an important factor that would determine the demand for financial services because this is a major source of farmers’ income. Where the value of maize harvested is low, the farmer has limited resources to save and less demand for saving and credit as most institutions use savings as collateral for granting loans. Alternatively, a farmer who earns high income from maize may have surplus cash to save and therefore is more likely to demand for financial services. This variable is specified as total maize sale from the previous year’s harvest and it is hypothesised to have a positive effect on the demand for financial services.Farmers may engage in off-farm income generating activities. Some activities require large amount of capital and higher returns. In addition, formal financial institutions develop products which fit the revenue and expenditure cycle of off-farm income activities which encourage the use of formal financial services. Therefore, the demand for savings is assumed to have a positive relationship with engagement in off-farm income generating activities. However, demand for credit is expected to correlate negatively with engagement in off-farm income generating activities. This variable [OATIV] is specified as a dummy variable which takes the value of 1 if the farmer has a secondary income source and 0 otherwise. The size of the household is assumed to positively influence the likelihood of using financial services. This is because larger households potentially may have higher consumption expenses which may affect their ability to save. Levels of saving tend to influence access to credit. Also larger households may have members who might occasionally be living outside their permanent residence and send money to, or receive money from, the household (Chen and Chivakul, 2008). This variable is measured as the number of individual household members taken care of by the respondents. This variable [HSIZ] is expected to have a negative effect on demand for savings and a positive effect on the demand for credit and money transfer services.Farmer’s household’s asset [TASET] is estimated as the sum of the resale value of household or domestic assets measured in Ghana Cedis (GH¢). This is used as a proxy for respondent’s wealth status in line with Rahji and Fakayode (2009). It is expected that the higher the value of the asset, the more likely farmers will use saving and credit facilities as these assets can be used as collateral to secure loans which would support income generation, and consequently savings. Therefore household asset is expected to have a positive effect on demand for savings, credit and money transfer services. The experience of shocks provides incentives for borrowing to better protect oneself from future shocks. The likelihood of taking up a loan increases with exposure to risk as the farmer is forced to make up for income losses due to adverse shocks. In this study we included three dummy variables on risk exposure following Steiner (2008). The first [HMSIK] takes on the value of 1 if a member of the farmer’s household experienced severe illness and ‘0’ otherwise. The second [HMDET] takes on the value of 1 if a member of the farmer’s family died and ‘0’ otherwise. The third [BVEST] takes value of 1 if the farmer experienced poor harvest and ‘0’ otherwise. It is expected that serious illness, the death of a family member and poor harvest is more likely to reduce demand for savings and money transfer services and increase demand for credit.Farmers who live far from financial service providers are less likely to contact the financial institution for more information than those who live close by. Thus it is assumed that a farmer’s perception [PROXIFA] of the distance to a financial institution would strongly reduce the likelihood of the farmer demanding financial services. This variable is specified as a dummy and takes the value of 1 if the farmer perceives the distance to be far and 0 otherwise.Farmers pass through different processes to use formal financial services which are operational modalities of the institution. Depending on the institution some of these processes are time-consuming, and difficult to understand. Farmers may prefer to demand financial services if they perceive the operational modalities to be satisfactory. Atieno (2001) reports, that in most cases access to financial services is created by the formal institutions through their operational modalities. This variable, [LenProFOR], is specified as a dummy variable which takes a value 1 if the farmer perceives the savings process and lending procedure as cumbersome or unsatisfactory and 0 otherwise. It is expected that this variable positively influences farmer’s demand for formal financial services. If the farmer perceives the lending rate of formal financial institution to be high, he is less likely to demand financial services from this institution. This variable [INTER] is expected to have a negative effect on demand for formal financial services. Since most of the farmers save in order to access credit, this would also negatively affect their demand for savings. This variable is specified as a dummy variable which takes the value of 1 if the farmer perceives the lending rate to be too high and 0 otherwise.Farm size [FSIZE] is measured in hectares and used as a proxy for the scale of operation and it can also be used by lenders to estimate expected income of the borrower and therefore applicants’ repayment capacity. Large farm sizes are expected to increase demand for formal financial services which are expected to increase with farm size. The empirical model is specified as; | (9) |

The dependent variable, FORMAL is an unordered categorical variable which reflects the choice of financial services including savings; credit; money transfers; all the three services; and none of the financial services (the base category).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Formal Financial Institutions Operating in the Study Area

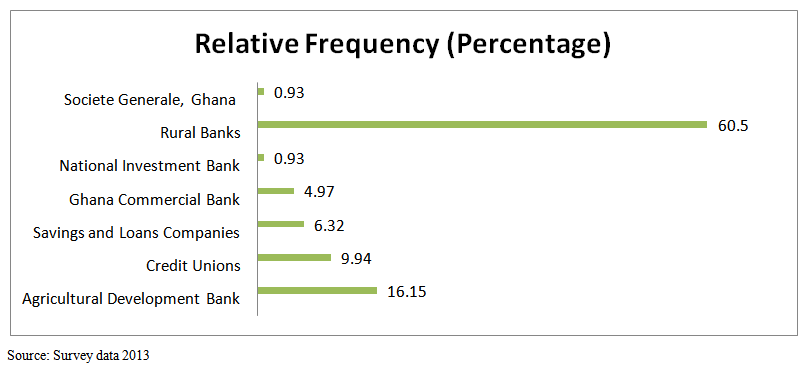

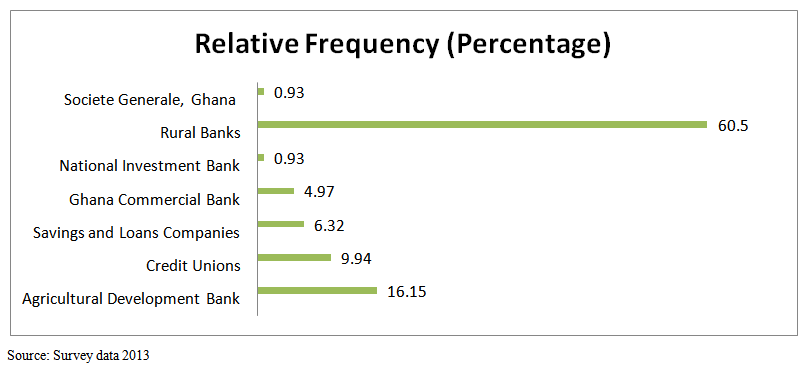

The study identified 11 universal banks, 14 rural banks, 7 savings and loans companies, 6 credit unions and 1 non-governmental financial organisation operating within the study area. The most patronised formal financial institutions by the respondents are rural banks (60.5%) followed by the Agricultural Development Bank with 16.15% (See Figure 1). | Figure 1. Formal Financial Institutions used by the Respondents |

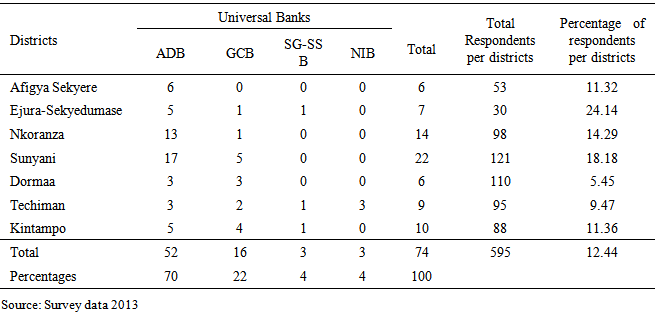

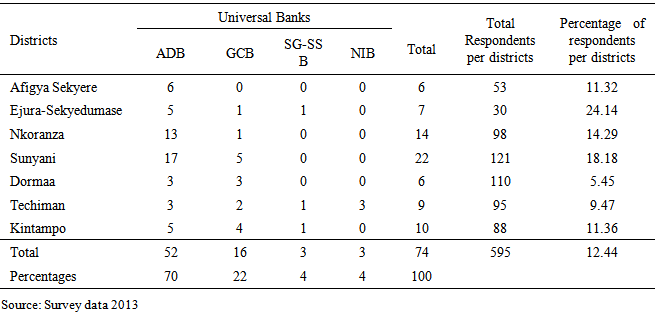

Table 1 presents the distribution of users of services of universal banks. Seventy percent of a total of 74 respondents who used universal banks, used Agricultural Development Bank (ADB) and 22% used Ghana Commercial Bank. These results confirm the role played by ADB in offering financial services to farmers. The popularity of ADB among universal banks can be attributed to the fact that they offer credit facilities to small scale farmers as the managed funds are used to target small scale farmers. In addition, they also have more branches than the other universal banks in the study area. Agricultural credit facilities offered by ADB have been supported by the managed funds provided by government (MoFA, 2006). Table 1. Universal Bank Usage Across Districts

|

| |

|

Managed funds are monies given to the financial institution to disburse to a target group under prescribed conditions; the institution is responsible for recovery. These managed funds usually attract the base rate interest and the beneficiaries of this credit facility are designated by the donors or their agents. Discussion with ADB credit officers at the bank’s branches in the study area revealed that loan repayment by the beneficiaries of managed funds is always poor. They attributed poor repayment to the poor creditworthiness assessment done by the facilitators in selecting beneficiaries.In all, only 12% of the respondents used the services of universal banks. The low patronage of universal banks was attributed to cumbersome operational modalities (account opening and loan application procedures) and the inability of these banks to offer agricultural credit to farmers.

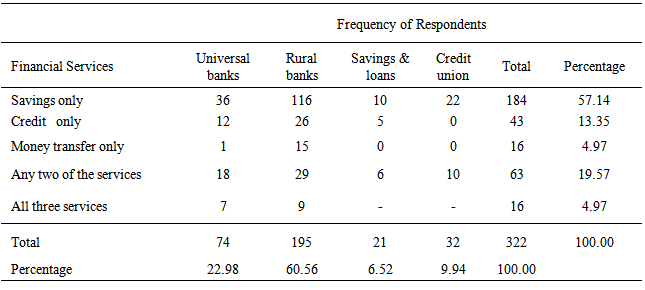

3.2. Formal Financial Services Used by the Respondents

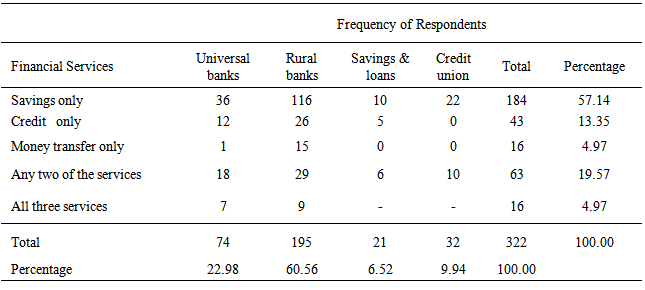

Formal financial services used by the respondents are savings, credit and money transfers. The distribution of respondents by type of service and by service provider is presented in Table 2.Table 2. Formal Financial Services used by the Respondents

|

| |

|

The savings product is the most popular among the services used by the respondents within the formal financial market segment. About 57% of the respondents used the savings product while less than 14% used credit facilities and about 5% used money transfer services. These results support the findings of GHAMFIN (2003) that the formal financial system in Ghana is strongly oriented towards savings mobilisation. The last row of Table 2 indicates that rural banks served about 61% of the respondents, followed by universal banks and credit unions which provided financial services for about 23% and 10% of the respondents respectively.These results support the observations made earlier that rural banks are the most important formal institution in the study area in terms of provision of financial services to farmers.

3.3. Factors Influencing Demand for Formal Financial Services

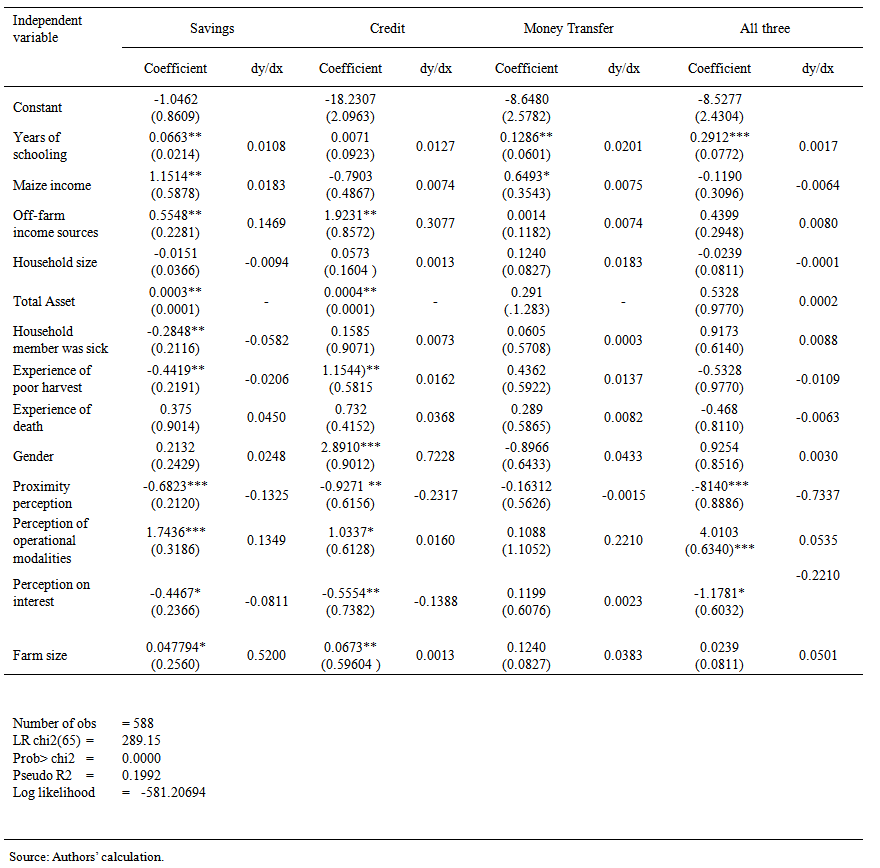

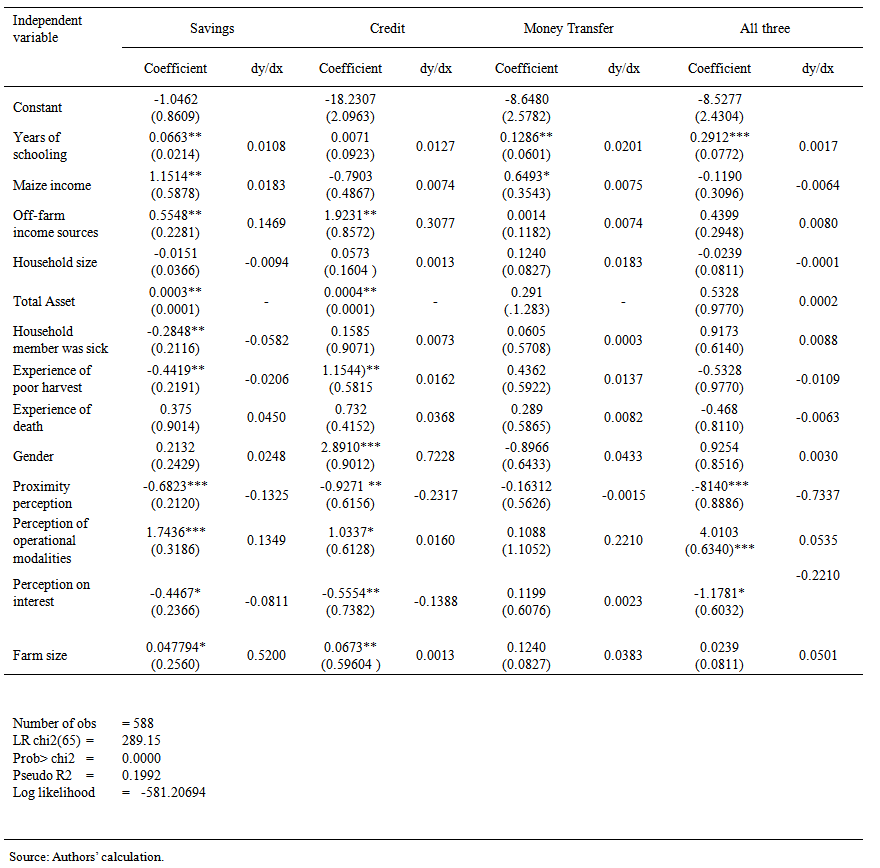

The estimated coefficients of the multinomial logit model, along with the levels of significance and marginal effects are presented in Table 3. The likelihood ratio statistics as indicated by chi-square statistics are highly significant (P < 0.00001), suggesting the model has a strong explanatory power. The model was tested for the validity of the independence of the irrelevant alternatives (IIA) assumptions by using the Hausman test for IIA.  | Table 3. Parameter Estimates and Marginal Effects of the Multinomial Logit on Demand for Formal Financial Services |

The test failed to reject the null hypothesis of independence of the demand for financial services options suggesting that the multinomial logit specification is appropriate to model demand for formal financial services. It must be noted that the marginal effects measure the expected change in probability of a particular choice being made with respect to a unit change in a continuous independent variable. In all cases the estimated coefficients of the independent variables are compared with the base category. The coefficients and marginal values of education are positive across all the options indicating a positive relationship between education and demand for formal financial services. As can be observed in Table 3 the coefficient is significant for savings at 5%, money transfer at 5% and all three services at 1%. A unit increase in number of years of schooling would result in a 1. 08% increase in proportion of respondents using savings and 2.01% and 0.17% increase in proportion of respondents using money transfer and all three financial services respectively. The previous year’s maize income has a positive and significant effect on demand for savings and money transfer services. This implies that if farmers earn more from maize production activities in one year, they are more likely to save in the following year. In addition, the coefficient of credit is negative though not statistically significant implying that an increase in the previous year’s maize income has the tendency of reducing demand for credit which means that farmers can support their consumption and productive activities with increased maize revenue. A cedi increase in maize income increases the likelihood for savings by 1.83% and money transfer services by 0.75%. Engagement in off-farm income generating activities significantly increases the likelihood of demand for saving and credit. This is because farmers who engaged in off-farm income generating activities tend to generate additional income, which increases their demand for savings.This improves their savings and increases the balance on account, consequently increasing their demand for credit. Engagement in off-farm income generating activities increases the probability of demand for saving by 41% and credit by 30%. Total asset, has a positive effect on demand for savings and credit and this indicates that wealthy farmers are more likely to save and demand credit. The experience of serious illness by a household member has a statistically significant and negative effect on demand for savings. The experience of serious illness of a household member decreases the likelihood of using formal saving by 5.82%. Poor harvest significantly influences demand for savings negatively and demand for credit positively. This may be due to the fact that their income levels are affected negatively, and consequently they do not have surplus to save thus they demand loans to support their consumption and investment activities. As can be seen from Table 3, farmers who experience poor harvest are 2.06% less likely to save and 1.6% more likely to demand credit. The coefficient of gender was positive for all the options and significant for demand for credit at 1%. This implies that male farmers are more likely to demand formal credit compared to their female counterparts. This is because male farmers have larger scale of operations, have higher expenses and hence are more likely to demand credit to support their activities. A male farmer is 72% more likely than a female farmer, to demand formal credit. The coefficients of a farmer’s perception on proximity to the nearest formal financial institution is negative across all the options and significant for saving at 1%, credit and all three options at 5% and 1% respectively. The results indicate that farmers who perceive the distance between their residence and location of the formal financial institution to be too far are less likely to demand financial services from these institutions. Specifically farmers who perceive the distance to be far are 13% less likely to demand savings, 23% and 73% less likely to demand credit and all three financial services respectively. This may be attributed to the fact that it might not be easy for them to have physical presence at the institution to transact business. As can be observed in Table 3the coefficients of operational modalities were positive across all the options and significant for savings at 5%, credit at 10% and all the three services at 1%. Farmers who perceive operational modalities of formal financial institutions to be satisfactory are 13% more likely to save, 61% more likely to demand credit and 5% more likely to demand all three financial services than those who perceive operational modalities as unsatisfactory. The coefficients of the perception of maize farmers that interest rates are high were found to be negative and significant for savings, credit and all the options. This finding of negative influence of interest rate charged on demand for formal financial services suggests that interest rates charged by financial institutions influence farmers demand for their services. Farmers who perceive lending rates to be high are 8% less likely to demand savings, 13.8% less likely to demand formal credit and 22% less likely to demand all three financial services.Farm size is related positively to demand for formal financial services. However, it is only statistically significant for savings and credit because the owners of large farms have higher capital requirements and earn higher revenue when there is a good harvest. Thus they tend to have a higher demand for credit and savings facilities. In addition, some of the formal institutions set farm size as an eligibility criterion for borrowers and this encourages farmers with larger farm sizes to use credit.

4. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Patronage of universal banks by the farmers is negatively affected by their availability or presence within the districts, cumbersome procedures for opening accounts and for applying for loans. Thus farmers’ access to formal financial services from universal banks can be improved through establishment of agencies at the district capitals and major towns within the districts, and streamlining procedures for accessing their services. Reduction in lending rates would increase use of credit facilities by farmers as banks which offer lower lending rates are patronised by more farmers. The frequency of savings and absence of agricultural credit by savings and loans companies and credit unions have contributed to the low level of usage among the farmers. Therefore, reduction in frequency of savings contribution and development of agricultural credit programmes by these institutions would result in increased use of their services by farmers. However, it is important to acknowledge the fact that most of the formal financial institutions are profit making entities and would only establish agencies, reduce lending rates and develop products for agricultural credit programme if only they see it as profitable. Thus the government needs to play a role by offering them incentives. This can take the form of reduced tax rates of managed funds for onward lending to farmers at a reduced rate. Since the recovery of loans from managed funds is poor because of inadequate assessment of creditworthiness, banks and providers of the funds should partner to ensure adequate assessment of credit worthiness and sensitisation on the obligations of borrowers so as to improve loan recovery and sustain agricultural credit. Furthermore, there is the need for formal institutions to engage in awareness creation and education of farmers on money transfer services to promote usage. Additional income from non-farm sources has the potential of increasing farmers’ use of formal financial services, hence farmers should be encouraged and supported to go into off-farm income generation activities. The results from the multinomial logit indicate that farmers’ socio-economic characteristics such as education, previous year’s maize income and engagement in off-farm income generating activities and farm size significantly and positively influence the use of formal financial services. Thus any policy that aims at increasing farm sizes, maize income and promoting off-farm income generating activities of the farmers would increase farmers’ access to formal financial services. Service providers can also use these factors as indicators of the sources of demand for their services and target them in the promotion of their services.

References

| [1] | Asiedu–Mante, E. 2005. Integrating Financial Services into Poverty Reduction Strategies: Institutional experience in Ghana. A paper presented at the regional workshop on integrating financial services into poverty reduction strategies. Abuja, Nigeria, September 13-15, 2005 |

| [2] | Atieno, R. 2000. Formal and Informal Institutions’ Lending Policies and Access to Credit by Small Scale Enterprises in Kenya: An Empirical Assessment, AERC Research Paper 111 |

| [3] | Basu, A., Blavy, R., and Yulek, M. 2004. ‘Microfinance in Africa: Experience and lessons from selected African countries’. IMF Working Paper WP/04/174.Washington, DC International Monetary Fund. |

| [4] | Bendig M., Giesbert L., and Steiner, S. 2009. Savings, Credit and Insurance: Household Demand for Formal Financial Services in Rural Ghana. GIGA working paper No.94. |

| [5] | Ekumah, E. K., and Essel, T. T. 2001. Gender Access to Credit under Ghana’s financial sector reform: A case study of two rural banks in Central Region of Ghana. IFLIP Research Paper No 01-4. |

| [6] | Chen Chen, K. and Chivakul, M. 2008. What drives household borrowing and credit constraints? Evidence from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Imf Working Paper 08/202. |

| [7] | Gallardo, J. 2006. Strategic Alliances to Scale Up Financial Services in Rural Areas. Washington, DC: World Bank. |

| [8] | Ghana Microfinance Institutions Network (GHAMFIN) 2003. Census of Micro Credit NGOs, Community-Based Organizations and Self Help Groups in Ghana, Accra, GHAMFIN, draft report prepared by Asamoah & Williams Consulting. |

| [9] | Giné, X. and Yang, D. 2009. Insurance, Credit, and Technology Adoption: Field Experimental Evidence from Malawi Journal of Development Economics Volume 89, Issue 1, Pages 1-11 |

| [10] | Green, W. H. 2000. Econometric Analysis, 4th ed. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. |

| [11] | Honohan, P. 2006. Household Financial Assets in the Process of Development, Policy Research Working Paper 3965, Washington DC: World Bank. |

| [12] | Institute of Statistical, Social and Economic Research 2008 The State of the Ghanaian Economy in 2007, University of Ghana pp 28, 128-130. |

| [13] | Johnson, S. 2006. Gender and microfinance; Guideline for good practice. Bath, UK: University of Bath Press. |

| [14] | Khalid, M. 2003. Access to Formal and Quasi Formal Credit by Smallholder Farmers and Artisanal Fishermen: A case study of Zanzibar. Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Environment and Cooperation, Zanzibar, Tanzania Research Report No. 036 |

| [15] | Ledgerwood, J. and White, V. 2006. Transforming microfinance institutions Providing full financial services to the poor, Washington DC: World Bank. |

| [16] | Maddala, G.S. 1999. Limited Dependent and Qualitative Variables in Economics, Cambridge University Press. Pp 223-228 |

| [17] | Ministry of Food and Agriculture 2009. Agriculture in Ghana Facts and Figures, 2009. |

| [18] | Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA). 2006. Programme for the promotion of perennial crops in Ghana available at http://mofa.gov.gh/ |

| [19] | Rahji, M. A. Y. and Fakayode, S.B. 2009. A multinomial logit Analysis of Agricultural Credit Rationing by commercial Banks in Nigeria .International Research Journal of Finance and Economics (24) 2009 |

| [20] | Steiner, S. 2008. Determinants of the use of financial services in rural Ghana: Implications for social protection, Brooks World Poverty Institute, University of Manchester. |

| [21] | World Bank. 2005. Gender and the impact of credit and transfers. Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Network. (No.104). |

| [22] | World Bank 2008. Finance for all? Policies and pitfalls in expanding access. Washington DC: World Bank. |

and

and  modelled as:

modelled as:

denotes the vector of observations on the variable X for farmer i, and

denotes the vector of observations on the variable X for farmer i, and  and e are parameters to be estimated and the error term respectively. In equation 1,

and e are parameters to be estimated and the error term respectively. In equation 1,  is not observed; instead we observe the choice made by the respondents. Each respondent will fall into the

is not observed; instead we observe the choice made by the respondents. Each respondent will fall into the  category, for

category, for  with some probability.Let

with some probability.Let  be the probabilities associated with these five possible choices available to the farmers. The probability

be the probabilities associated with these five possible choices available to the farmers. The probability  of respondents using a particular alterative is conceptualised to depend on variable

of respondents using a particular alterative is conceptualised to depend on variable  and with e assuming a logistic distribution. The probability of a respondent i using a particular option j can be presented in a multinomial logit form as:

and with e assuming a logistic distribution. The probability of a respondent i using a particular option j can be presented in a multinomial logit form as:

the likelihood function for the multinomial logit model can be written as:

the likelihood function for the multinomial logit model can be written as:

is a function of parameters

is a function of parameters  and regressors defined in equation 2, with first order condition for the MLE of

and regressors defined in equation 2, with first order condition for the MLE of  as:

as:

has been normalised to zero since all the probabilities must sum up to 1 (Maddala, 1999; Green, 2000). Therefore, out of the five choices, only four distinct sets of parameters are identified and estimated. The probability of the respondent using the base category can be formulated as:

has been normalised to zero since all the probabilities must sum up to 1 (Maddala, 1999; Green, 2000). Therefore, out of the five choices, only four distinct sets of parameters are identified and estimated. The probability of the respondent using the base category can be formulated as:

) measures the probability that an individual would use a financial service relative to the base category of not using any financial services. The estimated coefficient for each choice therefore reflects the effect of

) measures the probability that an individual would use a financial service relative to the base category of not using any financial services. The estimated coefficient for each choice therefore reflects the effect of  on the likelihood of the respondent’s demand for that financial service(s) relative to the reference option. In this study, non-use of any of the financial services is taken as the base category against which the rest of the alternatives are compared.

on the likelihood of the respondent’s demand for that financial service(s) relative to the reference option. In this study, non-use of any of the financial services is taken as the base category against which the rest of the alternatives are compared.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML