-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2014; 4(2): 135-143

doi:10.5923/j.ijaf.20140402.14

Characteristics and Adaptive Potential of Sweetpotato Cultivars Grown in Uganda

Saul Daniel Ddumba1, 2, Jeffrey Andresen1, Sieglinde S. Snapp3

1Department of Geography, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA

2Department of Geography, Geo-informatics & Climatic Sciences, Makerere University, P.O Box 7062, Kampala, Uganda

3Department of Crop and Soil Sciences and Department of Horticulture, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA

Correspondence to: Saul Daniel Ddumba, Department of Geography, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper reviews the characteristics of sweetpotato cultivars grown in Uganda using published literature and highlights the role of farmers’ involvement and other stakeholders in sweetpotato production. Sweetpotatoes have a high potential in improving food security in East Africa due to their general high tolerance to heat and water stress, rich vitamin A content, and relatively short growing period. Being known as a reserve crop, sweetpotato is either mono-cropped or inter or relay cropped with other crops. In order to select a variety to grow during a given season, farmers use characteristics such as yield, time to reach maturity, root color, root size, root shape, root quality, sweetness, pest and disease resistance, and marketability. Among the non-orange fleshed sweetpotato cultivars, NASPOT 1, Tanzania, Tororo-3, New Kawogo and Bwanjule rank highly in terms of the characteristics. The Orange fleshed sweetpotato cultivars with most preference include NASPOT 10, Kakamega, NASPOT 5 and NASPOT 8. It should be noted, however, that the importance and popularity of a given variety varies across different parts of Uganda. More participatory plant breeding, variety selection and adaptive research should be encouraged and supported by the research donor agencies to ensure that relevant adaptive strategies are identified and implemented by the smallholder farmers without neglecting the community-based and non-profit organizations that support farmers. This will help in preparing vulnerable communities against the impacts of climate change and other constraints that severely affect sweetpotato production.

Keywords: Sweetpotato, Cultivars, Participatory action research, Uganda

Cite this paper: Saul Daniel Ddumba, Jeffrey Andresen, Sieglinde S. Snapp, Characteristics and Adaptive Potential of Sweetpotato Cultivars Grown in Uganda, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2014, pp. 135-143. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20140402.14.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Sweetpotatoes are among the world’s most important staple crops [1] that are likely to contribute significantly to increasing food security and reducing hunger. The crop that is presently grown in most tropical countries originated from South America, was taken to Europe and later spread to other parts of the world with the Portuguese bringing it to Africa [2]. Due to the high adaptive potential of sweetpotatoes, Africa is among the top producers with highest production coming from Uganda in East Africa [3].The importance of sweetptotato in the diet of Uganda is clearly evident from the statistics of food produced in the country. On a national scale, for example, it ranks fourth among the most important staple foods contributing about 9% of the country’s production with the remainder coming from plantains (18%), cassava (13%), maize (11%), sweetpotato (9%), beans (6%), wheat (2%), rice (2%), and others (39%) [4]. Basing on the nutrition content of all the staple crops, sweetpotato has a much higher nutrition values than most other crops, as it can provide carbohydrates, proteins and vitamins [5]. Of particular importance is that sweetpotatoes, especially the orange fleshed sweetpotato (OFS) cultivars, are rich in vitamins A, B2 and C; iron; moderate levels of calcium ash; and fiber [3]. In spite the high production and high nutritious values of sweetpotatoes in Uganda, malnutrition problems still do exist in the country. For example, 20% of children and 19% of women have vitamin A deficiencies [6]. Vitamin A deficiency (VAD) has negative effects such as increased exposure of children to common illness, stunted growth, development, vision and reduced immune systems [7] and VAD claims between 15,000 to 60,000 lives annually [8]. These statistics paint a picture that something is probably wrong. One possibility could be that the crops produced and consumed, especially sweetpotato cultivars may not be rich enough in vitamins, or that vitamin rich crops are produced and consumed during a particular season leaving families to live without any source of vitamins for the rest of the time. There is therefore a need for all stakeholders to devise means to address this problem, one way of which is to have a collection of the crop characteristics and then identify ways to help families have a quality diet across the year.Climate variability and change is also feared to lead to malnutrition and hunger as changes in temperature and rainfall will negatively affect crop production. For example, Uganda’s temperature is projected to increase from 1.5℃ in the next 20 years to 4.3℃ by 2080 [9] which will lead to changes in the distribution of agro-ecological zones and soil moisture, and shortening of the growing seasons [10]. The drought and heat tolerant C3 plants such as roots and tubers like sweetpotatoes and cassava will be the most preferred to C4 plants such as cereals whose yields especially for maize will be greatly reduced. Therefore, with all the challenges raised above, sweetpotato production in Uganda is one possibility in addressing malnutrition problems and ensuring food security to the increasing country’s population of the nutrition and growth development advantages it has over other crops. Unfortunately, Sweetpotato production in Uganda has not received good research attention [3], [5]. The aim of this paper is to integrate and identify the most productive sweetpotato cultivars from existing literature using characteristics including maturity period, yield, root quality, resistance to pests and diseases, root flesh color, and abundance. Having a collection of information about the sweetpotato cultivars that have been researched on is valuable to researchers interested in crop breeding, modeling and pathology studies. The paper begins by providing an overview of the sweetpotato farming systems in Uganda and a detailed analysis of the sweetpotato cultivars based on published work and the organizations that help in the dissemination of planting materials and any other relevant information to the farmers. The paper presents the major constraints experienced by farmers and finally, highlights the role of participatory and adaptive research in developing suitable crop cultivars and general sweetpotato production systems in Africa.

2. Sweetpotato Farming Systems in Uganda

- Farming systems of sweetpotato in Uganda vary from mono-cropping to mixed cropping systems. Sweetpotato is either mono-cropped or inter or relay cropped with other crops such as legumes e.g., beans, or cereals like maize, millet and sorghum [3], [5]. This enables households especially in rural areas to have a constant food supply and various food options during the year. Sweetpotato is normally grown in crop rotations which are decided upon differently by farmers in the region in Uganda and more importantly, according to the resources and priorities of a given household [3]. The main source of planting materials for growing sweetpotatoes by households is by use of domestic waste water to grow vines and planting sweetpotato roots in a nursery, watering them for 4-6 days and then transplanted to actual plots.Sweetpotato is planted on ridges, mounds of about 0.5m high and occupying an area of about 1 square meters [11] or on flat ground. It is planted following the bimodal part of the rainfall between March-May and October – December [3], [5]. Planting materials are mainly vines and sometimes sizeable roots accumulated by households using irrigation and domestic waste water [12]. In drier areas, planting materials are conserved by planting vines in areas with available water such as wetlands, areas near water holes, and sometimes by physical watering in the backyard [12]. Various sweetpotato cultivars with varying maturation times are grown on the same plot during the same season and sometimes at different times in order to allow for a long time of harvest. Most subsistence households practice in-ground storage and piecemeal harvest where by only enough roots are harvested [13], [14], [15]. This form of staggering planting and planting of different cultivars enable the households to go through dry periods by having mature roots stored in the ground for up to six months, and piecemeal harvesting. However, the sweetpotato production still undergoes a number of challenges and constraints that have led to low yields in Uganda.

3. Sweetpotato Varieties in Uganda

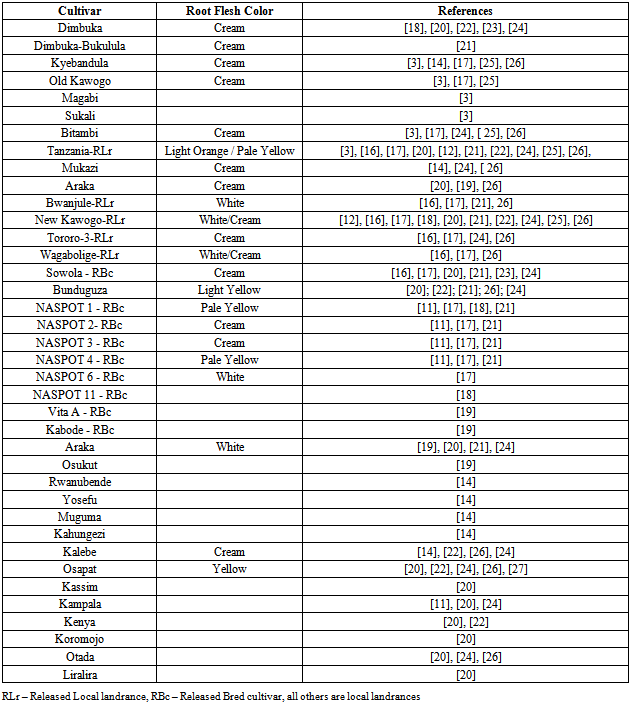

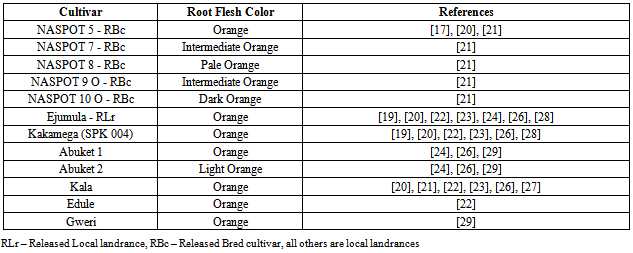

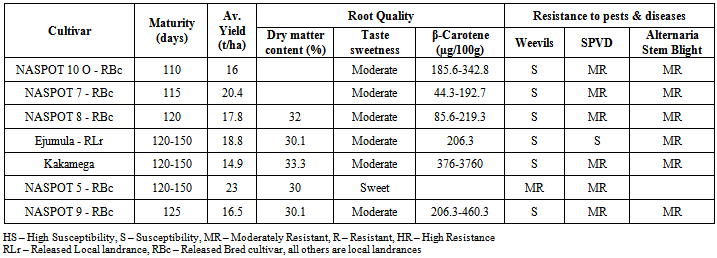

- The choice and preference of sweetpotato cultivars by farmers differ from individual to individual. Farmers use characteristics such as yield, time to reach maturity, root color, root size, root shape, root quality, sweetness, pest and disease resistance, and marketability [3]. There has been a considerable amount research on the characteristics of sweetpotato cultivars grown in Uganda. Some studies provide detailed information about the characteristics of cultivars while others provide much less information. The cultivars are either local landraces existing within communities or officially released landraces got from other communities and distributed across the country, and others are bred and tested at the National Crops Resources Research Institute (NaCRRI) in Namulonge and later released to communities. In this paper, we review literature and collect characteristics on all the recorded cultivars and we make comparisons of the cultivars. The synthesized information from this review is useful for researchers and other stakeholders interested in understanding sweetpotato production in Uganda. This work focuses on cultivars that have been published in articles, but it should be noted that there are many more cultivars existing in Uganda whose characteristics have not yet been documented. The cultivars are presented under two categories; non-orange fleshed sweetpotato cultivars (Table 1) and orange fleshed sweetpotato (OFSP) cultivars (Table 2). Of the non-OFSP, the released cultivars include: Tanzania, Bwanjule, New Kawogo, Tororo 3, Wagabolige, and Sowola [16]; NASPOT 1, NASPOT 2, NASPOT 3, NASPOT 4, and NASPOT 6 [17]; NASPOT 11 [18]; and, Vita A and Kabode [19]. It is not very clear from literature whether the last two cultivars are non-OFSP or OFSP. The released OFSP include: NASPOT 5 [17]; Ejumula and Kakamega or SPK 004 [20]; and NASPOT 7, NASPOT 8, NASPOT 9 O’, and NASPOT 10 O’ [21].

|

|

3.1. Methods and Approaches used to Evaluate Sweetpotato Characteristics

- This section provides a brief description of the methods and approaches used without singling out a specific reference. The reader should refer to the references provided in Tables 1 and 2 for particular methods of interest. For all cultivars, planting of vine-tip cuttings of about 30 cm long was carried out using a randomized complete block design for a given number of trials. The maturity of the cultivars was determined by harvesting and measuring the storage root size and weight of a few sweetpotato plants using destructive sampling from field trials during a given growing season. Following harvesting, oven-drying of roots at 650C, and weighing of two replications of 500g samples of sliced roots, the dry matter content storage roots was expressed as the average percentage of dry weight to fresh weight. A scale of sweetness ranging from low, moderate to sweet was followed to establish the taste of cultivars. In order to effectively establish the taste and abundance of a particular cultivar, a questionnaire was used to collect information from farmers who participated in a given study. Beta-carotene content in storage roots was determined by using spectrophotometry at Makerere University in Uganda, following a standard protocol of high performance liquid chromatography. To establish the resistance of cultivars to pests and diseases, two approaches were used. The first approach involved scoring of sweetpotato virus disease (SPVD) and alternaria blight at 2.5 and 4.5 months after planting. The second approach was to score the damage of sweetpotato weevil at harvest. A 1-5 scale was used rate the disease and weevil damage, cracking, storage root sprouting and rotting. The scale used included; 1 – no apparent damage/not present, 2 – very little damage/few present, 3 – moderate damage / numbers present, 4 – considerable damage/numbers present, and, 5 - severe damage/very high numbers present.

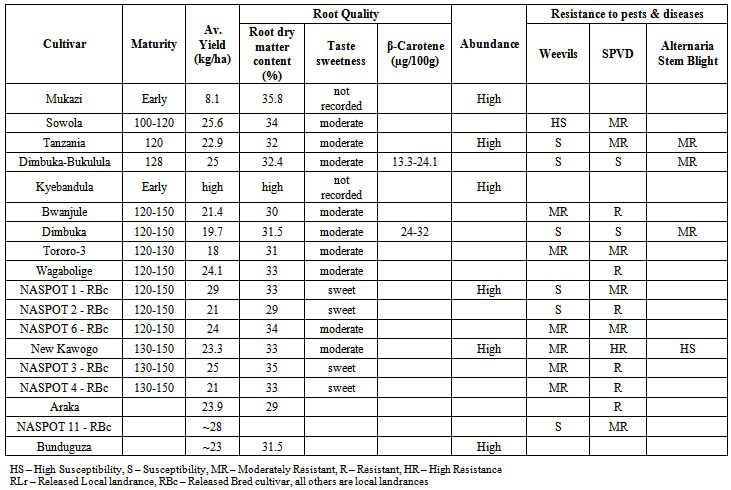

3.2. Maturity

- An analysis of information in Table 3 from literature shows that Sowola takes 100-120 days to reach maturity while others like Tanzania, Dimbuka-Bukulula, Bwanjule, Dimbuka, Tororo-3, Wagabolige, NASPOT 1, NASPOT 2 and NASPOT 6 take between 120-130 days to mature. Mukazi and Kyebandula were also ranked among the early maturing cultivars in a study carried out by [14] but no specific maturity date was provided. For the OFSP in Table 4, on the other hand, NASPOT 10 O and NASPOT 7 take 110 days and 115 days respectively to reach maturity while NASPOT 8, Ejumula, Kakamega, NASPOT 5 and NASPOT 9 take between 120-150 days.

| Table 3. Characteristics of selected non-orange fleshed cultivars |

3.3. Yield

- In terms of yield, non-OFSP cultivars in Table 3 give the highest yield with an average yield of 29t/ha for NASPOT 1, Sowola (25.6 t/ha), Dimbuka-Bukulula and NASPOT 3 (25t/ha), Napot 6, Wagabolige and Araka (23.9). A most recently released variety NASPOT 11 was also reported to have yielded as much as NASPOT 1[18]. The rest of the non-OFSP cultivars give below 21t/ha. The OFSP cultivars with highest yield are NASPOT 5 with 23t/ha and NASPOT 7 with 20.4t/ha.The root dry matter content for most sweetpotato cultivars is over 30% but Mukazi has the highest value of 35.8%, followed by NASPOT 3 with 35%, Sowola, and NASPOT 6 with 34% (Table 3). For the OFSP cultivars, the highest root dry matter content is given by Kakamega with 33.3%. This is a very important ratio for breeders to understand the proportion of biomass partitioning for a sweetpotato plant. A high ratio shows that a good proportion of nutrients are used by the plant in developing roots.

3.4. Taste

- Taste is a very important factor used by consumers of sweetpotatoes in Uganda. A variety with a sweet taste is more preferred to one with less sweet taste. For the non-OFSP, the released cultivars NASPOT 1, NASPOT 2, NASPOT 3 and NASPOT 4 have sweet tastes and therefore may be consumed more than the local landraces (see Table 3). NASPOT 5 in Table 4 has a sweeter taste than the rest of the OFSP cultivars.

| Table 4. Characteristics of selected orange fleshed cultivars |

3.5. Abundance

- Abundance is also an important factor used by farmers to determine the cultivars they plan on planting in a given season. The more abundant cultivars vary for different regions in the country. However, the most common cultivars across the country include: Mukazi, NASPOT 1, Kyebandula, New Kawogo, Bitambi, Tanzania and Bunduguza [3], [14], [16], [17], [30]. The most common local cultivars per region from highest to low abundance include: Central – Dimbuka, Kalebe, New Kawogo, Silk, Munyera, Kyebandula; Eastern – Bunduguz a, Araka, Kigayire, Silk, Tanzania; Northern – Liralira, Koromojo, Nyakenya, Ombivu, Nyaromayo; Western – Kyebandula, Kahogo, Mugumira, Kyokyokyemba [30]. Tanzania is a regional variety as it is widely grown in East African countries and locally known by different names. For example, it is called SPN/O in Tanzania, Enaironi in Kenya, Chingovwa in Zambia and Kenya in Malawi [16].

3.6. Resistance to Pests and Diseases

- The literature considers mainly three categories; weevils, sweetpotato virus disease (SPVD) and alternaria stem blight (see Tables 3 and 4). Bwanjule, Tororo-3, NASPOT 6, New Kawogo, NASPOT 3 and NASPOT 4 and NASPOT 5 are moderately resistant to sweetpotato weevils. Most orange fleshed such as sweetpotato (OFSP) cultivars, and Sowola, Tanzania, Tororo-3, NASPOT 1 and NASPOT 6 are moderately resistant to SPVD. New Kawogo was reported to have a high resistance and Bwanjule, Wagabolige and NASPOT 2 are also resistant to SPVD. All OFSP cultivars, some non-OFSP cultivars such as Tanzania, Dimbuka- Bukulula and Dimbuka are moderately resistant to alternaria stem blight. Therefore, successful production of a variety in an area should put into consideration the nature and type of pests and diseases present in the area.

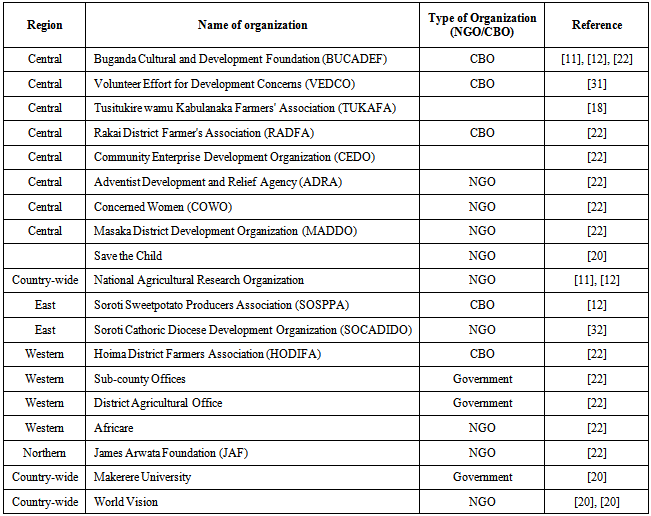

4. Farmer Support and Dissemination of Planting Materials

- The importance of this section is to highlight the organizations playing a significant role in the distribution of planting materials for the different cultivars and providing general support to sweetpotato farmers in Uganda. The organization are distributed across the country, see Table 5. The organizations are government, not for profit, or community based organizations (CBO). The organizations help in the multiplication and dissemination of new and improved sweetpotato cultivars, promotion of orange-fleshed sweetpotato to avert vitamin A deficiency. They also help in sensitization of farmers and all stakeholders about the importance of growing and consuming orange fleshed cultivars that are rich in vitamin A. Examples of such institutions include the ministry of Health in collaboration with Volunteer Efforts for Development Concerns (VEDCO) and the National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO) successfully conducted sensitizations in Luwero district in central Uganda in 2001 [31] and Save the Child (NGO), Makerere University, Department of Agri- cultural Extension, and World Vision sensitized stakeholders [20].

|

5. Constraints to Sweetpotato Production in Uganda

- Sweetpotato production is affected by a number of constraints that compromise its potential in being very productive. The average yield of sweetpotato (4t/ha) is much lower than the potential yield of 25t/ha. Various constraints responsible for the low production include; pest and diseases, drought, vine scarcity, lack of capital, high labor requirements, poor yields, low prices, animal destroy crop, lack of land, poor markets, and crop rotting [19], [22]. The major disease constraints affecting sweetpotatoes include the sweetpotato virus disease (SPVD), weevil, and physiological lack of vigor [12]. Major sweetpotato pests include sweetpotato weevil (Cylas punticolis, C.brunneus, and C. formicarius), butterflies, mole rats, other rodents and wild beasts [5], [3], [12]. Intercropping sweetpotato with corn, soybean and corn reduces the damage of sweetpotato weevil [33] while pesticides and fertilizer application, and rouging of the diseased plants [3], [12] are the main ways to regulate virus diseases of the crop. Like in most developing countries, fertilizer application in sweetpotato farming systems in Uganda is very low leading to poor yields [34]. However, even in instances of low farm inputs, some sweetpotato cultivars give a higher yield than others.

6. Participatory and Adaptive Research on Sweetpotato Production

- Participatory breeding and adaptive research has unique contributions to make to the constraints faced by sweetpotato smallholder farmers in Uganda and African countries in general. Farmers, community-based and non-profit organizations, and agricultural extension have been instrumental in enhancing production and research in sweetpotato agricultural systems in Uganda. Some literature has highlighted the involvement of farmers in participatory plant breeding and participatory variety selection (e.g., [11], [18]) with positive results in terms of the final product from the research and also from the farmers experience and fulfillment in contributing towards the whole research process. There is a wide body of literature on participatory research approach but only a few selected articles are used in this section to briefly orient the reader. Then a few success stories for sweetpotatoes and other crops are presented to highlight the importance of this approach in enhancing agricultural production. In an agricultural context, participatory research can be functional oriented and empowering involving farmers [35] and other stakeholders such as extension officers, non-governmental organizations and scientists. Participatory research improves crops and genetic diversity, the efficiency of the research services in identifying adaptive technologies, and empowers rural communities to influence the agendas of and to benefit from the knowledge in formal research [36], [37], [38]. In designing a model of participatory research for bean improvement, [39] observed that farmers’ participation is critical in research because farmers usually know the problem and needs on their farms, and whether they will use the new variety or not. Therefore, in order to achieve the most of out of participatory research, the research should be collaborative [36], [40], [41], [42] contractual, consultative and collegiate [36], decentralized [37], [43], [44] and should lead to a specific local adaptation and intra-varietal diversity [44].Participatory plant breeding (PPB) and participatory varietal selection (PVS) has been widely used on various crops in Africa. Scientists and farmers used PVS to identify preferred sweetpotato cultivars (e.g., [11], [45]), and PPB to lead to official release of a new sweetpotato variety called NASPOT 11 [18]. More details on PPB and PVS can be found in [40], [46], [47], and [42]. PPB was also successfully used in bush beans in Rwanda [48] and in Hondurus [38], cassava production in Tanzania [49] and in Ghana to develop superior cassava cultivars [50]. On-farm participatory research has also been used in improving soil organic matter and soil nutrient management in southern Africa [51], [52], [53], [54]. In most of these examples, the involvement of farmers in research helps scientists to consider other factors such as taste, color, and farmer preferences that would not have otherwise been considered in formal plant breeding. Therefore, participatory research should be encouraged and used more often to help in advancing adapting technologies in smallholder farmers. This research approach will play a significant role in helping communities to adapt to the impacts of climate change on agriculture especially for the most vulnerable communities. However, participatory research has some challenges such as high costs, some attributes such as taste and color may be hard to measure, and sometimes there is need for additional training by scientists such as learning of farmers languages [37]. Some of these challenges can be addressed by working with scientists within the area who may know the local language and carefully planning the research process before actual implementation.

7. Conclusions

- There is still a need to conduct more research on sweetpotatoes in Uganda and in East Africa in general. This will not only help in reducing malnutrition problems experienced in the countries, but it will also prepare the country against the impacts of the projected changes in climate which are likely to affect many crops. From the characteristics of cultivars discussed above, it is important to note that no single characteristic can be used to determine the best variety to select although such knowledge is useful in determining the potential and impact one variety might have over the other. For example, some people may prefer cultivars with a sweet taste while others may be interested in early maturing cultivars. Under such scenarios, the use of participatory research approaches is important in coming up with the best option. Equally important, is the involvement of governmental and community-based organizations, and research institutions that help in supporting the farmers. All the success stories of released cultivars in Uganda have been attained as a result of a joint effort from all organizations.Finally, as more growth characteristics become available for different cultivars of sweetpotato, there is need to carry out sweetpotato modeling to assess the impact of changes in environmental conditions especially climate and management practices on sweetpotato production. The information to be generated from modeling work will be highly valuable especially to the sweetpotato breeders who normally take over 10 years of crop breeding before a new variety that can perform well in the changing environmental conditions is released.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The United States Department of State through the Fulbright Science and Technology Program and Michigan AgBioResearch are acknowledged for funding this research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML