-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry

p-ISSN: 2165-882X e-ISSN: 2165-8846

2014; 4(2): 53-61

doi:10.5923/j.ijaf.20140402.01

Innovation is Anything but Business as Usual: An Analysis of Innovation Practices in the Irish Food Industry

Carol Ledwith1, Kathryn Cormican2

1OSCAIL, Dublin City University, Dublin 9, Ireland

2College of Engineering & Informatics, National University of Ireland, Galway Ireland

Correspondence to: Kathryn Cormican, College of Engineering & Informatics, National University of Ireland, Galway Ireland.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The Irish food industry is facing many challenges such as high costs; poor skill levels; inadequately structured supports coupled with specific consumer and retailer demands. It is clear that the industry must become more innovative to overcome these challenges and exploit potential opportunities. However, little research has been conducted in this field and there is no comprehensive innovation guide available to the Irish food industry. This paper attempts to address this deficit and expand the discussion on innovation management practices. We synthesized the literature to identify key determinants of innovation management practices and analyzed six innovative and successful food companies in Ireland relative to best practice. Our results show that there is a need to focus on consumers and markets; product and process innovation and technological and market knowledge. We then developed a roadmap that integrates customer needs, product evolution and innovation best practice. This roadmap provides a framework for decision makers to plan and coordinate future developments. This paper contributes to knowledge by (a) identifying the drivers and determinants of innovation in the food industry (b) conducting new empirical research using case study analysis and (c) developing a framework for integrating the management of innovation in the Irish food industry.

Keywords: Innovation Management, Irish Food Industry, Innovation Roadmap, Best Practices, Case Study

Cite this paper: Carol Ledwith, Kathryn Cormican, Innovation is Anything but Business as Usual: An Analysis of Innovation Practices in the Irish Food Industry, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2014, pp. 53-61. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20140402.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- This Irish food industry is fast becoming the most important sector for employment and growth. There are 135,000 employees in the agri-food sector in Ireland and the industry turns over approximately €24 billion per annum. The future of the industry is bright and many publications have anticipated growth. The national body providing integrated research, advisory and training services to the agriculture and food industry foresees increases in gross output value. They predict that it will double from €20 billion to €40 billion by 2030. Key commentators suggest, however, that the industry is facing many challenges such as high costs, poor skill levels, lack of industry scale, inadequately structured supports and specific consumer and retailer demands. Product and process innovation are a means of unlocking the industry’s potential and mitigating against these challenge (Naranjo-Valencia et al., 2011; Rama, 2008; Avermaete et al., 2003; Grunert et al., 1997). However, it is unclear how Irish food companies should grow by innovation as there is no comprehensive guide available. Consequently, the goal of this study is to analyse the industry in order to understand the drivers, challenges and innovation processes that are in place. From this analysis an innovation road map was developed to help guide professionals and policy makers in order to support and improve the industry’s performance. The expectation is that this guide will aid the development of a collaborative, innovative and consumer led industry that will drive high value exports. The beneficiaries of this research are professionals and policy makers in the food industry. By using the road map, industry professionals will be able to identify the inputs and outputs of an effective innovation process. For policy makers, it will help to determine the weaknesses in the existing processes and provide guidance on ways to eliminate these shortcomings.

2. Determinants of Innovation

- Many studies have outlined the drivers and determinants of a firm’s propensity to innovate (Capitanio et al., 2010; Galizzi and Venturini, 2008; Avermaete et al., 2003). We synthesised the literature and identified key drivers and determinants that are consistently found to facilitate innovation. Particular attention is paid to literature relevant to the food industry where possible.

2.1. Management of the Innovation Process

- The innovation process is considered disorderly and made up of some of the most complex systems known (Harmancioglu et al., 2007). It has been widely written, that in order to accelerate innovation programmes many companies have implemented systematic processes for moving a new product though the various stages of the development lifecycle (Crossan and Apaydin 2010; Harmancioglu et al., 2007). In the past innovation processes were organised in a closed linear fashion. However researchers are now calling for a more ‘open work environment for optimising innovation’ Berkhout, et al., (2010). Indeed Tuulenmäki and Välikangas, (2011) propose a ‘flash development model’ where the innovation outcome is reached very quickly. Central to good management practice is the concept of project review practices. These are considered vital for learning (Schmidt et al., 2009; Stockstrom and Herstatt, 2008; Koners and Goffin, 2007).

2.2. Open Innovation

- Open innovation is a strategy that has received much attention in the literature in recent years. It refers to the idea of two or more parties working together to create and deliver a new product, technology or service (Enkel, et al., 2009; Keupp and Gassmann, 2009; Chesbrough and Appleyard, 2007). Three core open innovation processes can be defined; the outside-in process, the inside-out process and the coupled process. The outside-in process refers to a company acquiring knowledge and capability though outside links e.g. suppliers or customers. The inside-out process refers to commercialising ideas and inventions through the sale of intellectual property and the coupled process refers to co-creation with complementary partners through alliances (Enkel et al., 2009). Research suggests that it is important to find the correct balance between open and closed innovation in order to get the best out of both (Enkel et al., 2009; Neyer et al. 2009). It seems that the success of implementing these strategies depends on the ‘cognitive distance’ between the participating companies (Gassmann et al., 2010).

2.3. Consumer and Market Orientation

- Successful new product performance depends on having a ‘unique and superior product’. This is achieved by effective needs analysis and clear opportunity identification. A comprehensive understanding of consumer preferences will help the food industry to predict and prepare for their future opportunities (Capitanio et al. 2010; Galizzi and Venturini 2008). Consequently the ‘voice of the customer’ should be at the centre of any plan to develop new products (Bharadwaj et al. 2012). A voice of the customer initiative is designed to capture customer needs, preferences and expectations, and organize them into a hierarchy of needs. Products and services can then be developed that meet the needs of the market.

2.4. Brands, Own Label Activity and Retailer Power

- A study looking at the corporate reputation for product innovation found that consumers show higher levels of excitement towards innovative firms (Henard and Dacin, 2010). Private label or branded manufacturers serve markets differently and consequently have different strategies. This also impacts on how they innovate (Beverland et al., 2010; Christensen, 2008 Traill and Meulenberg, 2002). On one hand companies competing on brand equity focus on continuous innovation (Beverland et al., 2010; Beverland, while food companies developing own label products often have low levels of R&D intensity (Senker and Mangematin, 2008). Manufacturers of brands see those competing on own label products as competitors. However, consumers are price sensitive and see high value in the own label products (Goldsmith et al., 2010).

2.5. Knowledge and Technology Transfer

- The assimilation, transfer and application of knowledge has been identified as a key factor for innovation (Ma and McSweeney, 2008; Gopalkrishnan and Santoro, 2004; Cormican and O’Sullivan, 2003). Brannback and Wiklund (2001) found that managing these processes is vital to the Finish food industry success. Many researchers highlight the importance of inter-firm relations to promote knowledge and technology transfer (Braun and Hadwiger, 2011; Capitanio 2010; Avermaete et al. 2003). The importance of links to government is highlighted in the literature. Hartwich and Negro (2010) found that there are benefits from both informal and formal collaborations between companies and external partners (e.g. government) in New Zealand’s dairy industry. However research suggests that government aids must be tailored for the company type and the innovation type (Traill and Meulenberg, 2002).

2.6. Leadership and Human Capital

- Capitanio et al. (2010) believe that management skills and human capital are key determinants for innovation. Human capital is developed through training and education aimed at updating competencies, capabilities and skills. Dakhli and Clercq (2004) make the distinction between different types of human capital; firm specific (i.e. knowledge and skills that are valuable only within a specific firm); industry specific (i.e. knowledge derived from experience specific to an industry) and individual (i.e. knowledge that is applicable to a broad range of firms and industries). The involvement of all employees in the innovation process is seen as key to successful innovation (Kesting and Ulhoi, 2010; Neyer et al., 2009).

2.7. Organisational Structure and Culture

- Organisational culture is seen as another key determinant of innovation (Naranjo-Valencia et al., 2011; Belassi et al., 2007). According to Zien and Buckler (1997) innovative companies ‘share a set of characteristics, qualities and behaviours that differentiates them from other less innovative companies’. Clearly there are many factors that enable a culture conducive to innovation such a promoting reciprocal trust; focusing on outcomes rather than actions; challenging the status quo and tolerating or even encouraging failure. Innovation culture encompasses the intention to be innovative, the infrastructure to support innovation, and the operational environments to commercialise an innovation (Sharifirad and Ataei, 2012; Dobni, 2008). Naranjo-Valencia et al. (2010) identified that formal hierarchical structures can inhibit innovation. Berkhout et al. (2010) identified that innovation is part of a ‘socio-technical framework’ that it cannot be managed in a linear way but in a multifunctional way with an entrepreneur who can steer it.

3. Research Methodology

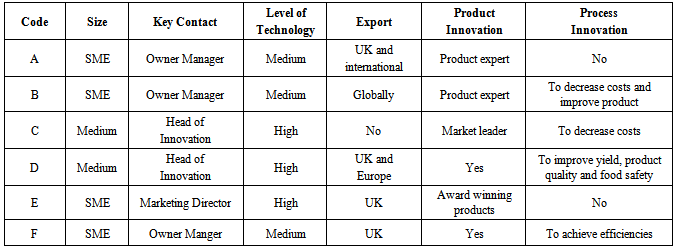

- An inductive case study approach is used in this study as it is a valuable way of examining complex real-life situations. There is much debate in the literature about the appropriate number of cases to use. Eisenhardt (1989) recommends a sample size of four to ten organizations (or sites) while Yin (2009) recommends between six and nine cases. Many researchers contend that multiple cases increase the explanatory power and generalisability of the data collection process (Remenyi et al, 1998; Miles and Huberman 1994). However, cases must be carefully selected so that they match the purpose of the study (structural representation) and produce similar results (literal replication) (Voss et al., 2002; Yin, 2009).Consequently a purposive non-probability sample of six small to medium sized innovative Irish Food Companies was selected on the basis of their product innovation activity (see table 1). Merriam (1998) indicates that a non-probability sample is effective when, as in this study, the research is exploring what is occurring. Sample selection was dictated by analytical (rather than statistical) generalisation and replication in accordance with best practice. To guarantee no ‘participant or observer bias response’ (Robson, 2002), the individuals contacted were unknown to the researchers. A series of in-depth semi-structured interviews was used to capture data and ‘obtain descriptions’ in each case site (Kvale and Brinkmann 2009). Specific questions were derived from the theoretical constructs. The questions were pilot tested on three employees in the Food Industry and was modified to ensure that the correct information was gathered.

|

- Care was taken to ensure rigour and objectivity in the study. Evidence was collected from multiple sources and triangulated. During the interviews, the answers to the questions were recorded by hand. Templates ensured that the information was recorded in the same way for each study. Case notes were written up within a day of the interview and the reports were sent back to the respondents for review. Clarifications and amendments were made where necessary. Whilst these activities ensured construct validity and increased the reliability of the study, the use of a protocol and replication logic across the case sites helped to maintain external validity. Analysis of the findings was based on the theoretical propositions and a chain of evidence was maintained. This satisfies Yin’s (2009) requirement of linking the data to the proposition. The data was analysed by carrying out cross case synthesis and from this it was possible to draw the conclusions. This approach satisfies the requirement of interpreting the findings (Voss et al., 2002).

4. Case Study Findings

4.1. Product and Process Innovation

- All of the companies studied claim that product innovation is core to their business. The companies are either considered product experts by the retailers (A and B), market leaders (C, E) or award winners (F). This is important to the companies as it gives them more influence in their product category when dealing with the retailers. Company D is a business to business supplier, supplying ingredients to major global brands.Three of the six companies (C, D and E) studied have sophisticated custom made stage gate processes that are considered vital to their new product development introduction strategy. The companies described the processes as being very structured with clearly laid out stages. Projects are run by dedicated project managers. Company B is using a system of regular meetings to plan its new product development activity. Company F is using a simplified version of a new product development process and see it as a way of focussing the team. Of the companies carrying out post launch reviews (C, D, E) none of them claimed to be satisfied with their post launch review execution. Company A, does not have a process in place but recognises that this will have to be rectified as the business expands. Process innovation is present in 4 of the 6 case studies (Companies B, C, D and F). It is used to reduce cost (B and C), increase line efficiency (F) and improve food safety (D). Company C and to a lesser extent companies B and F described it as a way to innovate on product.The term ‘open innovation’ is familiar to 3 of the 6 companies. Whilst it is not currently part of any responding companies formal strategy 3 companies are working on ways to make the concept relevant to the food industry.

4.2. Consumer and Market Orientation

- We found that consumer and market orientation is the most important driver of innovation. A wide variety of mechanisms are used to access customers’ needs wants and expectations such as direct conversations with consumers, suppliers, buyers, distributors, product testing, trade magazines, store visits, trends, networking, monitoring the competition or simply by being prepared to look and listen at all times. Travelling abroad, attending trade fairs and restaurant safaris at home and abroad are also very important sources of consumer insight. In more recent times companies are displaying consumer orientation by using social media like blogs, Facebook and Twitter.For all of the companies (expect F) travel to foreign markets is considered one of the most important ways of getting consumer insights and market knowledge. For the larger food companies (C and D), the presence of an insight manager and innovation centres are conduits to getting these insights.Science and innovation centres enable the companies to conduct ideation sessions with cross functional teams, focus groups, consumers and customers. In company C, 60% of the work at the innovation centre is on ‘blue sky activity’. Structured and consumer focussed processes are also important to understanding consumers in companies C, D and E. Interestingly, companies A and F claimed that some consumers are reluctant to accept very innovative products as they are too radical. The companies try to overcome it by communicating and assuring consumers. They see this as a vital part of the product introduction process.

4.3. Brands, Own Label Activity and Retailer Power

- Having a brand is seen as being a very important driver of innovation. All the respondents confirmed that being either a private label manufacturer or a branded producer impacts on how companies innovate. By continuous brand innovation, the producers stay ahead of retailers’ own brands and other potential competitors. Brands are a way of achieving this for companies A, B, C, E and F. Company D is not a producer of branded products but is a business to business ingredient supplier to many strong international brands. The common consensus from the analysis is that retailer own-label brands and innovation do not align well together. For brand producing companies, their decision to produce retailer own label brands is a strategic one. Company E made a conscious decision to avoid retailer brands, commenting that it is difficult to do both. They see them as two very different business models. For the companies producing own label product (A, B, F), it can be a help to a company in its early stages (F) and it is a way of adding tonnage to the factory (F, B).The companies confirm that retailer power is increasing and is becoming more aggressive; this can be mitigated by having a brand, being a product expert in the field and continuously bringing new ideas to the market. This is seen very positively by retailers and equips the companies with more power and influence (Company A, C and E). To overcome retailer aggression, Company F has reduced product margins but is not reducing product quality. Company F commented that own label brands are becoming powerful and there is a trend with European retailers to try and replicate this model.

4.4. Knowledge and Technology Transfer

- Most companies gather their own consumer insights; however the national development agency is also used by companies. Without exception, data from this agency is considered very useful for market intelligence and learning how to access foreign markets. In many instances suppliers are used to capture technical know-how (companies B, C, E and F). We learned that these links were related to ingredient supports more than for equipment.Links to the authority responsible for research and development, training and advisory services in the agri-food sector were varied with only three companies of the six companies analysed actively accessing the resource. Company C stated that they thought the organisation was too academic and not relevant to industry. Similarly we found that responding companies do not have strong links with third level institutions other general support agencies. Company B, C and E are collaborating with other brands in other food sectors. However, this is only seen as a benefit when in the area of breakthrough innovation and they advise that the collaboration must align with the strategic goals of the organisations. Finally we found that links to non-food sectors are not significant.

4.5. Leadership and Human Capital

- Another driver of innovation investigated was human capital. In company A, the owner managers are the main drivers of innovation. In the smaller companies the innovation or development teams report to the company owner and in the larger companies the innovation teams report to the marketing director or to a senior business employee. For the privately owned companies, the owner manager’s leadership or vision is considered to be vital to innovation.However a representative of company A noted that the production team are not inclined to propose ideas because of the owner manager’s active role in innovation. Company B outlined that there are two owners and they divide their expertise into two areas. They commented that it is important for them to ensure that they run the business as one unit and not two separate units.The bigger companies with innovation centres (Company C and D), indicate that there is a specific skill set required in the consumer foods sector. The sector needs skills in product development, processing and packaging. There are also requirements for focus group facilitators, language skills to deal with foreign customers and insight managers or business development managers for understanding consumer requirements.Company C and F outlined the importance of having knowledgeable employees who are able to communicate with external companies and support bodies.

4.6. Organisational Structure and Culture

- In all of the companies analysed noted the importance of a strong team ethos and in the bigger companies a requirement for cross functional activity drawing from all parts of the business. Company A (a large company) identified that there is a demand for all members to exhibit a high degree of flexibility and passion for the business. For the mid-size companies (B, E and F) there are new product development teams present. They are considered vital to the company and must also exhibit high levels of capability, flexibility and team effort.Company C and D, built a bespoke research centre for their research teams. This was considered an important decision for innovation as it allows time and space needed for creativity. Company F tries to encourage the questioning of conventional thinking within their business while Company B cite the importance of a blameless culture.

5. Discussion

- All responding companies see innovation as a key imperative for survival and growth. This is in line with the literature that suggests that innovation is crucial for survival in the food industry (Rama, 2008; Avermaete, 2003; Grunert et al., 1997). The literature states that product and process innovations must be complimentary to each other (Damanpour, 2010; Brewin et al 2009). However our study found that responding companies are innovating on product first and foremost and process innovation is less developed. Innovation levels are incremental in almost all the companies analysed. We learned that consumers are reluctant to accept truly innovative products. This finding concurs with Grunert et al., (1997). It is also reflective of Gallizzi and Venturini’s (2008) study on ‘path dependant inertia’ where consumers display risk aversion to new products. However companies can overcome this by communicating closely with the consumer. Post launch review is essential for improvement and learning (Schmidt et al., 2009; Stockstrom and Herstatt, 2008). However we found that none of the companies feel that this activity is optimised, therefore it should be a focus for the future. Open innovation is not currently part of the formal strategy of the companies studied. This is similar to Gassmann et al.’s (2010) findings. Enkel et al. (2009) identified that it is an area that should be balanced with closed innovation. The Irish food industry should consider open innovation as previous studies have shown that there are significant competitive advantages to be gained by food companies entering into product development alliances (Traitler et al., 2011; Sakar and Costa, 2008; Olsen et al., 2008). Companies can implement this strategy through integration with suppliers (Schiele, 2010) or cross industry innovation where approaches from one industry are applied to another (Enkel and Gassmann, 2010). However, there is a clear need for supports in the industry to help companies move from closed innovation strategies to open innovation, as reflected in Chiaroni et al.’s (2010) study.All companies are consumer focussed and market orientated; this is in line with best practice literature (Rese and Baier, 2011; Capitanio et al., 2010; Henard and Dacin, 2010; Galizzi and Venturini 2008). Cooper and Kleinschmidt (1987) outlined that the most important activities of a new product introduction process are the pre-development activities. This is seen in the companies that are carrying out focus group activities to identify customer needs and expectations. Also evident in the study is the difference between brand producers and private label producers. Our study confirmed that having a brand is critical to a company’s innovation strategy. This is in agreement with Beverland et al. (2010), Christensen (2008) and Traill and Meulenberg (2002). Knowledge access and transfer is the fuel for product development activity. A study by Brännback and Wiklund (2001) of the Finish food industry identified that knowledge management is vital to the industry’s success. It is evident that all of the companies studied display a large appetite for market knowledge, gathering it from every possible avenue. All companies stated that market orientation and consumer focus is at the centre of everything they do. However, there is less activity around sourcing technological knowledge. This is also evident in the low level interaction and partnerships between the technological centres in this country e.g. with support agencies or the third level institutions. Our study found that there is also a lack of technology transfer in the industry. This upholds the findings of other studies (Henchion et al., 2008; Kelly et al., 2008).Key to knowledge access and external links is two-way communication. This driver was not evident in the literature review but it is one that evolves from every aspect of the case study research. For example, we found that there is an onus on industry to feed its requirements back to the support bodies. There is also an onus on the supporting bodies to identify the needs of industry. By having this two-way communication, it would ensure that work carried out by the institutions is relevant to the industry. There may be a need also to tailor knowledge requirements for the types of business targeted as the requirements for artisan companies are very different to those of an international plc. This concurs with Rese and Baier’s (2011) findings on the importance of network partners.We found that a high degree of flexibility and team work is required for innovation particularly in the smaller companies. Cross functional activity is important in larger organisations. These findings align with Kesting and Ulhoi, (2010) and Neyer et al. (2009) who refer to employee driven innovation. They also concur with the findings of Oster (2010) who identified the importance of informal and organic innovation. The bigger companies spoke of the need for a specific skill set and knowledgeable employees. The need for time to think and reflect was also seen as important particularly in the bigger companies while the vision of the owner manager is critical in smaller companies.

6. Conclusions

- The Irish food industry is facing many challenges such as the economic downturn, high costs, poor skill levels, inadequately structured supports and specific consumer and retailer demands. However, there are many opportunities for the industry but it must become more innovative to deal with these challenges and increase competitive advantage.Our study identified a need for a more open and collaborative system of working in the food industry. In order for the industry to develop and grow to its full potential, the industry must work collaboratively with companies within the sector, with other sectors and with support structures. We found that all companies must strive to keep the consumer at the centre of all their innovation activities. The industry as a whole must become more knowledge based. Industries must strive to have knowledge available to them on consumer requirements and technical know-how. Food companies must focus on market opportunities abroad using branded products that meet consumer needs.The study has reviewed innovation practices in the food industry and developed a best practice roadmap based on our findings. This paper contributes to knowledge by (a) synthesising the drivers and determinants of innovation in the food industry (b) conducting new empirical research using case study analysis and (c) developing a framework for integrating the management of innovation in the Irish food industry. To investigate the area further it would be beneficial to apply the study’s findings to a company over a period of a year and use this as part of an action research study. Another option is to undertake a longitudinal study. Alternatively the findings could be used for comparative analysis in another sector e.g. the pharmaceutical industry.

7. Recommendations

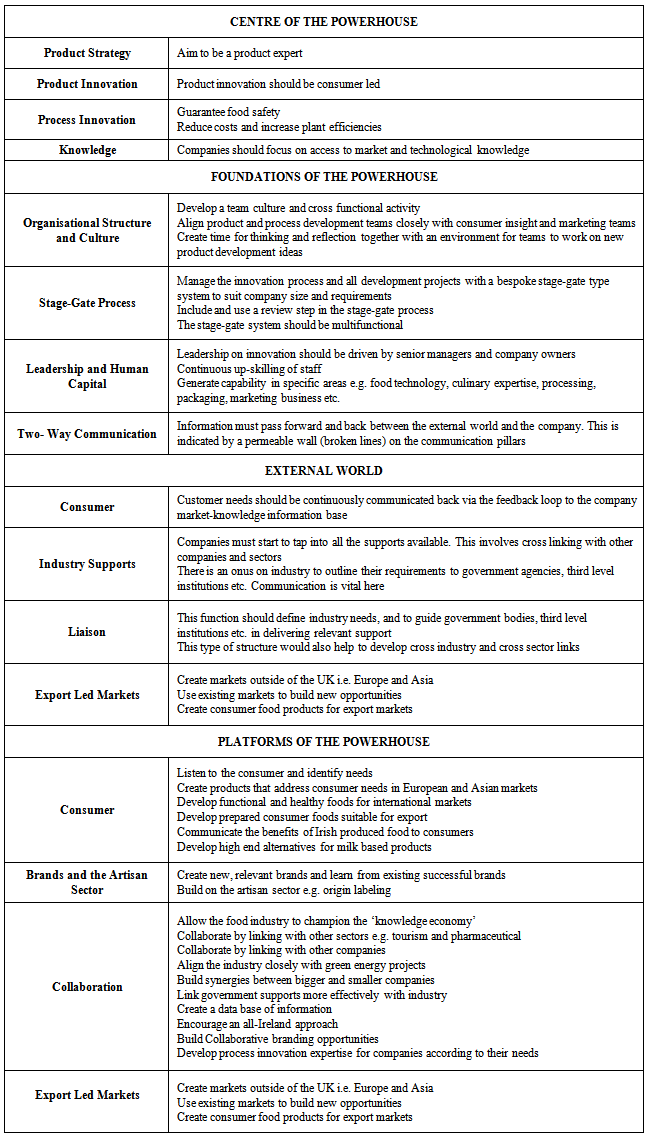

- Our recommendations centre on the assertion that the food industry should focus on an open innovation approach so that they can increase levels of innovation and leverage risk and work on a plan to address the issues outlined in the analysis above. We have developed a model called the Powerhouse of Open Innovation which synthesises the ley lessons from our analysis and can act as a road map for the industry (see Table 2).

|

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML