Bwagalilo Fadhili1, Evarist Liwa2, Riziki Shemdoe3

1Department of Geography, St John’s University of Tanzania, P. O. Box 47, Dodoma, Tanzania

2School of Geospatial Science and Technology, Ardhi University, P. O. Box 35124, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

3Institute of Human Settlement Studies, Ardhi University, P. O. Box 35124, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Correspondence to: Bwagalilo Fadhili, Department of Geography, St John’s University of Tanzania, P. O. Box 47, Dodoma, Tanzania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

Management of forests by strict protection is facing a great challenge of conservation and meeting people needs. While farmland trees management has the potential to help integrate protected areas with their surrounding landscapes, and mediate the livelihood demands of communities with the conservation goals of protected areas, still there is little support to it. Research on farmland trees focuses on private tree planting basing on types of tree species and marketability, but very seldom on policy and institutions that shape farmland tree management. Therefore assessing the policy and institutions that govern farmland trees management is important as to identify the gaps and opportunities for farmland trees management given by the available policies and institution. This paper provide an highlight on farmland trees governance outside protected areas with an assumption that, better management of trees on farms minimize pressure on protected areas forest resource of the east Usambara mountains. The eastern Usambara mountains are characterized with forest reserves, plantations as well as communities involved in small scale farming. Data were collected through Focus Group Discussion, in depth interviews using structured questionnaires, and checklist questionnaires. All were conducted in three villages namely; Misalai, Shambangeda and Kwatango, a total of 100 respondents were interviewed. Furthermore, data were also collected at the ward, district, regional and ministry levels. The findings have identified and documented different policies and institutions governing farmland trees at different levels. Challenges and opportunity are also identified in relation to existing policies and institutions and land tenure

Keywords:

Farmland Trees, Policies and Institutions (Governance)

Cite this paper: Bwagalilo Fadhili, Evarist Liwa, Riziki Shemdoe, Farmland Trees Governance outside Protected Area in Eastern Usambara Mountains, Tanzania, International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 3 No. 7, 2013, pp. 284-293. doi: 10.5923/j.ijaf.20130307.05.

1. Introduction

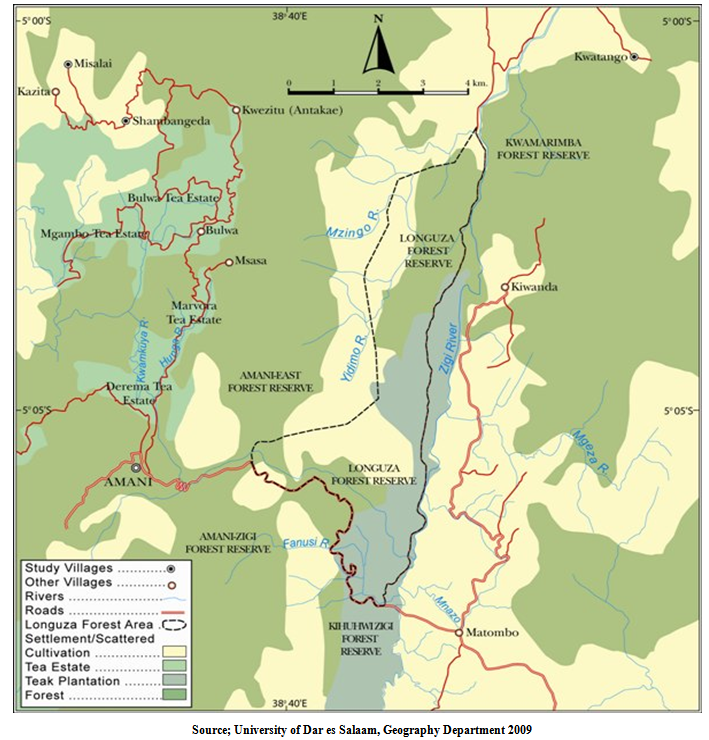

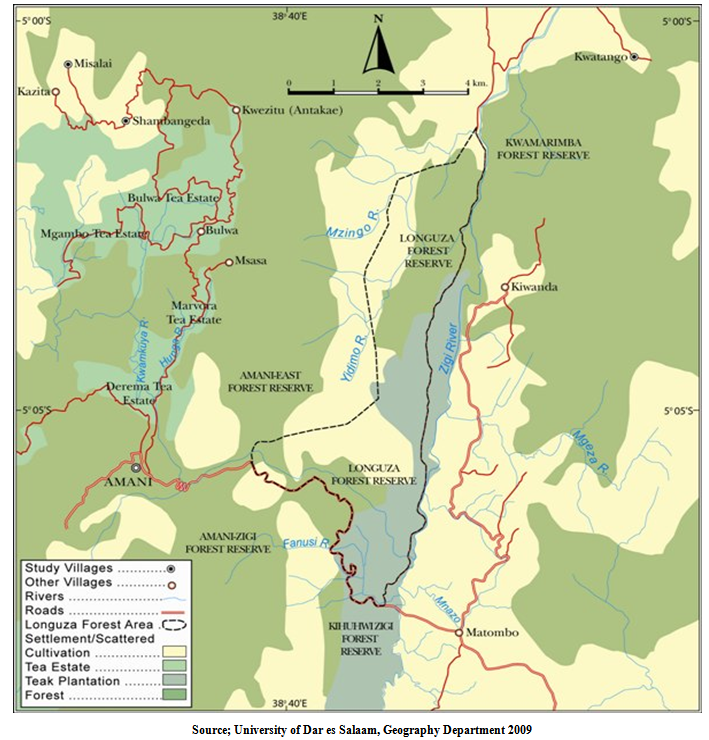

Tree on farms are very important for land and biodiversity conservation because they offer great opportunities to create habitats for wild species in agricultural land. Further- more they save for different socio-economic needs of the people. They are more important in area that harbour the world’s biologically richest and most threatened ecoregions, including the most of the global biodiversity hotspots[1]. The trees serve for both food and cash needs of the people of Africa. Moreover almost a quarter of the world’s population depends solely on farmland trees. According to the World Bank[2] almost 1.6- billion people in the world rely on forest resources for their livelihood and 1.2 billion people in developing countries use trees on farms[3]. The knowledge of complex role of trees in farmland has increased substantially over the past three decades. As a result, the potential for farmland trees to transform lives and landscapes is grasped now more than ever before. However, the potential contribution of farmland trees in the implementation of environment and development policies has not been fully harnessed[1]. Rather the emphasis is put much on establishing central managed forest resources. In Tanzania alone for example this is manifested by the proliferation of protected areas such as nature reserves and national parks which total about 14.5 million hectares as forest reserves including those within national parks and therefore managed by the government. This figure reflects the question of broadening and diversifying forest management which has internationally emerged as a key in the forest policy scheme. It has also emerged as an international political agenda since the 1992 Rio conference on environment and development[4]. Forests have also been addressed in a wide range of internationally agreed conventions and instruments like Convention on Biological Diversity, United Nations Forum for Forest, and United Nation Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC) et cetera and at national levels within national forest programmes (NFPs) and similar policy frameworks. Increasingly, high-level political priorities for forests are issues related to human well-being, such as poverty reduction and sustainable livelihoods, food security, human health, climate change and conflict mitigation[5]. All of these are policy and institutions related matters and are the marks of Tanzania forest management status today.Tanzania has about 33.5 million hectares of forests and woodlands, which is about 39.9% of the total land of Tanzania. Out of this total area more than 25% of Tanzania forest is in protected areas as described by IUCN[6]. Almost two thirds of the forest consists of woodlands on public land which is in intensive pressure from human activities[7]. Besides, this form of management is facing a great challenge of conservation and meeting people needs[8]. To strike the balance between conservation and meeting people needs, promoting farmland trees management will be of a solution. The manifestations of farmland trees importance are reflected from the service they provide to a household as well as biodiversity conservation. Tanzania’s concern on forest conservation is reflected by the policies, Acts and programmes that are meant to protect forest resources, for instance the national environmental policy 1997, the national forest policy 1998, the national environmental management Act 2004 and the national forest programme 2001-2010. These policies do not operate in isolation; they reflect international agreements on forest resources conservation. Of all these policies, the uncertainty arises on the position of farmland trees management as one of the strategies for forest management and how strongly is it supported by the existing policies and institutions. | Figure 1. Study area (Map) |

Despite of the both global and national level efforts and strategies to conserve forests and to implement sustainable forest management (SFM), deforestation and forest degradation have continued over the last decades[4, 5]. The interplay between various economic, social and development factors are causes of forest degradation. Similarly activities meeting local needs for instance the expansion of subsistence agriculture to feed the expanding population locally has also been the cause of deforestation[9]. Population growth, poverty, market and policy failure are some of the major underlying causes of deforestation in Tanzania, while agriculture, charcoal making and pit sawing activities being very significant. This is supported by the MNRT that about 37.4% of Tanzania forest and woodland habitat have been degraded between 1990-2005[10] Moreover deforestation is increasingly driven by increasing global demand for different global traded commodities including soy, palm oil, beef and timber. The problem is also exacerbated by the worlds growing demand for bio fuel,[11]. Therefore these needs have to be enhanced and made sustainable in a way that reduce pressure on protected areas, that is by promoting on farm’s trees management.Farmland trees management is described as, ‘a dynamic, ecologically based, natural resource management system that, through the integration of trees on farms and in the agricultural landscape, diversifies and sustains production for increased social, economic and environmental benefits for land users at all levels[12]; it is a deliberate management of trees on farms and in agricultural landscapes[13]; from Leakey and Ashley definitions, farmland trees management seem to be one of the way that seeks to sustain and stabilize rural livelihoods and in conjunction with biodiversity conservation by reducing pressure on existing protected natural resources. This notion is relative to the fact that protected areas such as nature reserves, national parks and game reserves are entrenched from strict surveillance surrounded by buffer zones that does not integrate people and ecosystem. However, to strike a balance of conservation and sustenance of rural livelihoods, there is a need to understand people and institutions as core components of ecosystems and landscapes[14], all these are policies and institutional related matters. Farmland trees management has much to contribute to tropical biodiversity conservation through reducing pressure on natural forests, creating or conserving habitat for wild biodiversity, or as a land use that enhances landscape connectivity. It also has the potential to help integrate protected areas with their surrounding landscapes, and mediate the livelihood demands of communities with the conservation goals of protected areas [12]. The practice aim at making sustainable use and management of trees, and the outcomes are directly or indirectly shaped by different actors including individual perceptions as well as existing policies and institutions. However, effective integration of farmland trees management ‘is a major policy and institutional challenge’ [15] that needs to have great attention. Local Government Authorities (LGA) plays a great role in forest resources management as backed up the National Environmental Management Act (NEMA, 2004). There are also programmes like the National strategy for growth and reduction of poverty (2005), National forest and bee keeping programme (2001-2010) which stress on forest resources conservation. The existence of Nongovernmentalorganizations such as Tanzania Forest Conservation Group (TFCG), Wildlife Conservation Society of Tanzania (WCST) for example directly or indirectly affects forest utilization and management[16]. All these together have a role to play in farmland trees management relative to the projected importance of farm trees. To understand a link and roles of existing policies and institutions governing farmland trees, a study was conducted in eastern Usambara Mountain. The area offers a great interplay between forest, farm estates and communities.Therefore, this paper aim at assessing local and national policies and institutions that shape farmland tree management outside protected areas and identify their constraints by:1.1. Identifying most important policies, institutions (including rules, regulations and norms) and socio-economic that determine individual and collective action influencing tree and forest resource management 1.2. Identifying the status of farmland trees management relative to land tenure and dependency level on forest resources 1.3. Investigating constraints that the policy scope poses for achieving biodiversity conservation through tree and forest management outside protected areas, including potential gaps or inconsistencies between agricultural and forest policies.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. The Study Area

The East Usambara Mountains are located in the district of Muheza, Mkinga and Korogwe, covering an area of about 1300km2 in Tanga region1. Three main land use categories existing in the east Usambara, which are territorial forest reserves (“central government forest reserves), forests on un-reserved lands; and forests on land with title deeds[8] The East Usambara Man and Biosphere reserve2 include among other forest blocks the Amani nature reserve, Nilo forest reserve and Mlinga forest reserve. The latter was formally under the local government until 1998 when the management was shifted to the central government with the aim of improving the management of the reserve. Two types of forests are found in Eastern Usambara, which are lowland and sub mountain rain forests. These are among the Eastern Arc Mountains with high biological diversity and endemism is included in the list of 24 "biological diversity hot spots" of the world[14; 19]. The mean of annual rainfall is 2200mm, with ranging between 20.6°C and 26°C for the upland and lowland respectivelyThe soils originate from biotite-hornblene garnet generic rocks with many quarts. The soils are more acidic, highly leached and have low fertility particularly in the upper altitude above 800m above sea level. The altitude ranges from 250m in coastal plains to 1506m at the highest peak. Except for Kwatango village which is located at the lowland the other two villages of the area studied are located in the uplands of the East Usambara Mountain, the villages are Misalai and Shambangeda.

2.2. Data Collection Methods

In this study different approaches to collect data and information were adopted. Data collection methods included Focus Group Discussion (FGD), structured questionnaire and Checklist. Under FGD data on forest resource accessibility and use were collected, not only that rules and regulations information that governs community interaction with the forest was also collected. Structured questionnaires were used to collect data on socio economic status of the households and household’s management of on farms trees. Checklists in this study were used to collect data at administrative level on policies, rules and regulations governing farmland trees outside protected area. Moreover checklist was used to collect data on challenges and opportunity facing the institutions on governing forestry at large.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Respondents Characteristics

3.1.1. Age, Sex, and Education Level of Respondents

3.1.1.1. Age

The majority of respondents 62% were less than 50 years old. Least responses were from respondents with less than 25 years 6%, while a reasonable number of response 32% came from respondents of more than 50 years of age. The insignificant number of respondents of less than 25 years is caused by the absence of young people in the villages who most of them work on tea estates as well as in the ongoing teak harvest.

3.1.1.2. Sex Distribution of the Respondents

The study area has a population of more than 16600 of both males and females and has more than 3600 households (30). This is the summation of population of two wards where the study was conducted. However from the drawn sample respondents 48% of respondents were female farmers and 52% of respondents were male farmers. Since the sample was randomly selected this small difference to the sex of respondents suggests equal representation of the population of the study area in terms of sex.

3.1.1.3. Education Level of Respondents

Almost every ward of the east Usambara has one secondary school and more primary schools. However all three villages of the study the sample have shown a huge percentage of respondents ending at primary school level, 78% are primary school leaver, 5% with secondary education and only 1% with tertiary education while 16% have not attended school at all. The reasons to the significant number of primary school leaver had been noted as the distance of the villages to the secondary schools, most of the secondary schools are located in wards centres, not only that, but also reluctance of parents in taking their children to school contributed greatly to this status.

3.2. Origin of Respondents

There are a significant number of immigrants in the area, 39% of the respondents are not natives of the east Usambara and some few natives of east Usambara are not residence of respective villages of the study. Most of the immigrants are the result of job opportunities from the plantations of tea and sisal estates. However, 61% of the respondents were found to be natives of the study area. However some of the natives do not belong to Sambaa tribe which is historically proven to be the indigenous of the area.

3.3. Household Size

A total number of 100 households were sampled for representation of three selected villages having an average household size of 4.6. The majority of household surveyed (63%) had household size of 1-5 peoples, 27% had households size of 5 peoples and above inclusive of very few households with more than 10 peoples. Table 4.3 presents person per household relative to 2002 national population census results on household size of Muheza district.

3.4. Primary Occupation of Respondents

The majority of respondents were farmers; those who had other activities also are engaging in farming. Generally results shows 28% of farmers per se, 19% agriculturist and other informal employment, 19% Agriculturist and Business (non- farm business), 9% formal employment and another 9% agriculture and butterfly keeping, 8% agriculture and livestock keeping, 6% agriculture and fishing, 1% unemployed the other 2% self employed that is 1% in business per se and another 1% formal employment (Teaching, Nursing, etc).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Policy and Institutions Influencing Farmland Trees Management

4.1.1. Policies and Institutions

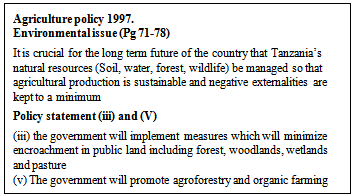

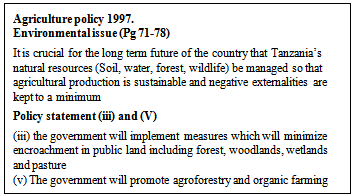

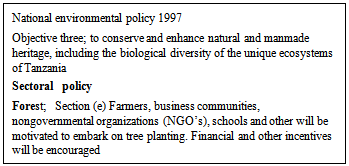

There are many policy documents that aim at ensuring better management of Tanzania’s natural resources but the main policies are; the national Agriculture policy 1997, the national environmental policy 1997 and the national forest policy 1998. The tables below provide short description of policies on the sections that directly affect farmland trees management. Table 1. Aspects of Agriculture Policy on Farmland Trees Management

|

| |

|

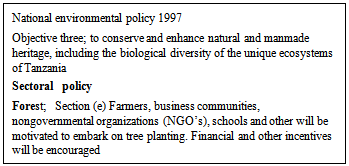

Although they appear to have a common interest in forest and trees issues still there are inconsistencies in the way how each policy stresses on the issue. The agricultural policy 1997 for instance states on promoting agroforestry but it does not present an explicit mechanism on how to attain that goal. On its environmental issues the policy only states on managing soil, water, forest and wildlife so that agriculture production is sustainable and minimizes the negative externalities. Although the policy document calls for implicit measures to minimize encroachment on forest still it does not give explicit strategies for it. The national environmental policy 1997 in contrast recognizes the threats towards forest and biodiversity as well as loss of wildlife habitats puts forward strategies to conserve forest resources and put forward instruments to protect these resources, one of the instruments is afforestation. Forest policy on the other directly and clearly states and support forest conservation through farmland trees management.Table 2. Aspects of Environmental Policy on Farmland Trees Management

|

| |

|

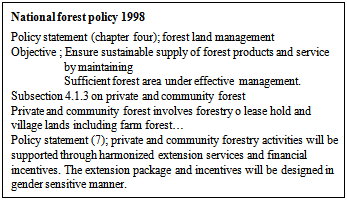

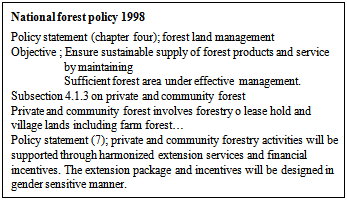

Table 3. Aspects of National Forest Policy on Farmland Trees Management

|

| |

|

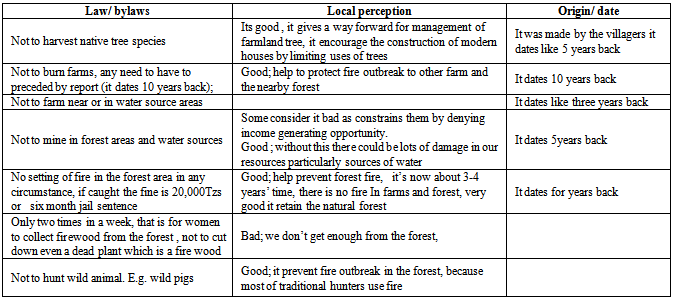

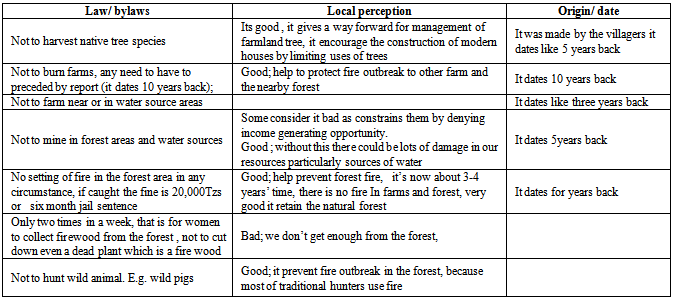

4.1.2. Bylaws and Institutions Affecting Farmland Tree

In all three villages of the study it was observed that, farmland tree are valued relatively to their importance in daily people livelihoods. This is reflected by the rules and regulations set by the villagers themselves to govern trees on their farms either deliberately planted or a natural grown one. Harvesting of trees and trees products have specific procedures to follow. Table 4. Bylaws affecting farmland trees and their local perceptions

|

| |

|

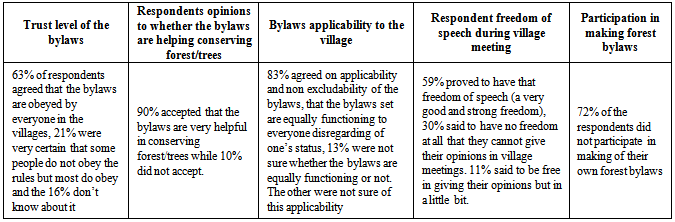

Table 5. Summary of Community Participation in Making Forest Bylaws

|

| |

|

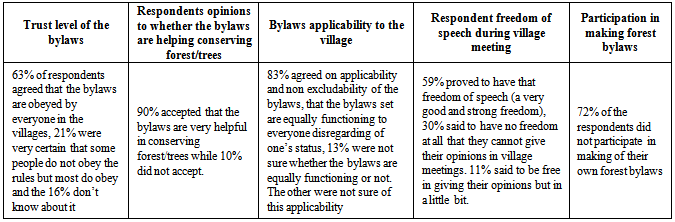

For instance in all villages of the study, village governments plays a greater role in managing farmland trees. For either a native or exotic tree species, no farmer is allowed to harvest a tree before consulting the village government. According to discussion with sample villagers the environmental/forest committees, any farmer who needs to harvest a tree from the farm has to send a formal request to the village government specifying the reasons for the harvest of the tree, the village government through itsenvironmental/forest committee will meet and evaluate the application and will make a physical survey to the location of the tree to be harvested. When the committee is satisfied with the application and the reason given, a farmer is granted a permission to harvest the tree (either cutting it down or harvesting of poles and withers). Furthermore a farmer is subjected to one step ahead, if the reason of cutting down the tree is of commercial purpose a farmer will have to consult the district forest officer At this stage a farmer is given a license to transport and sell the products to the market of his/her choice. However it was also explained that most farmers do not take the logs to the market on their own, buyers come in their villages and buy the trees. Buyers are also responsible for applying for a right to harvest, transport and sell the tree product. For the natives tree species available in east Usambara like Milicia excelsa, pterocarpus angolensis, cordial Africana and the related species the only reason that can be granted for cutting them down is either the tree is dead/dried up or it’s hazardous to the nearby community. Besides a significant number of the respondents are aware of the existing forest/trees bylaws in their villages, 60% are aware of the bylaws, 15% aware but not fully, 23% not aware while only 2% claimed to be not sure of their awareness to the bylaws. That’s makes an approximate of more than 75% of those aware of the bylaws. In all cases it was found that, managing trees on farm is taken by village governments and private institutions; to a very less extent district management is mentioned as one of the institutions that give a directly concerned with farmland trees management . However, the issue of forest/ trees governance had an awkward look as many of respondents claimed to have not participated in the selecting the village forest committee that will represent all village matters on trees and forest management. Results shows that only 28% of the respondents proved to have participated in the elections and 48% of respondents proved to have participated in village’s general meeting. This is not a satisfactory representation indicator of local people’s participation in farm trees management. It gives an indication of a missing aspect between the village government and the village community.Despite the dissatisfying participation in electing village government and village forest committee, there were bylaws formulated. Table below provides a summary of community participation in making forest bylaws and applicability of the existing bylaws. This could be concluded that despite low level of local people participation but the output of those few is highly acknowledged.

4.2. Farmland Trees Status

Relative to land size and ownership status of the household, it was also identified that, the average tree species per household was six. There was also a difference in the type of tree species per village. Misalai and Shambangeda villages both had most of Grevillea (grevillea robusta) tree species while the Kwatango village had most of Teak (Tectona grandis) tree species and mvule (Milicia excelsa). The only tree species that had been observed to be dominant in all three villages of the study is cedrela odorata. Weather differences between the upland villages (Misalai and Shambangeda) and the lowland village (Kwatango) were observed to be one of the reasons that cause specie dominance differences.

4.2.1. Dependence on Forest Resources

Almost 1.6 billion people in the world rely on trees and forest resource for their livelihood and 1.2 billion people in developing countries use trees on farms to generate food and cash[2, 3]. This situation was also revealed east Usambara. The people in the study area depend variously if forest/tree resources such as fuel woods, building poles, withers, thatches, traditional medicines, fruits (allanblakia for business purpose) and 30% of the respondents proved to have generating income from this wild fruit, etc. However majority of respondents obtain their forest resources from their farms. Out of 100 respondents 45% had their fuel wood coming from their farms, 11% from the village forest reserves while others had their fuel wood either from tea estates planted forests or other people’s farms. Building poles, withers and ropes which are very important trees resources in the villages had a very significant on farm source, 45% obtained these goods from farm trees, 14% from tea estates forests, 11% from other people’s farms. This has a very strong relationship to the existence of protected areas (forest) in this area that is the Amani nature reserve and the Longuza Teal plantation forest.

4.3. Constraints that the Policy and Institutions Scope Poses for Achieving Biodiversity Conservation Through Farmland Trees Management

4.3.1. Inconsistencies between the Agricultural and Forest Policies

There are many policy documents that are aimed at ensuring better management of Tanzania’s natural resources, as provided above are just few policies that have direct linkages to forest and trees. Although they appear to have a common interest in forest and trees issues still there are no consistencies in the way how each policy stresses on the issue. The agriculture policy 1997 for instance states on promoting agroforestry but it does not present an explicit mechanism on how to attain that goal. On its environmental issues the policy only states on managing soil, water, forest and wildlife so that agriculture production is sustainable and minimizes the negative externalities. The policy document calls for implicit measures to minimize encroachment on forest still it does not give explicit strategies for it. The national environmental policy 1997 in contrast recognizes the threats towards forest and biodiversity as well as loss of wildlife habitats puts forward strategies to conserve forest resources and put forward instruments to protect these resources, one of the instruments is afforestation. The national forest policy 1998 gives policy statements that ensure that forest and forest products are kept in supply. The policy statements clearly states on promotion of landscape level of forest biodiversity conservation (by landscape the policy refers to forest/trees on every piece of land). The policy states that. “Private and community forestry activities will be supported through harmonized through extension services and financial incentives. The extension package and incentives will be designed in a gender sensitive manner (URT, 1998)”. The policy further gives the incentives to farmland trees that farmers will be entitled to owner rights of indigenous species including reserved species and not only planted exotic ones. On ecosystem conservation and management component the policy through its policy statement number sixteen, states on conservation involving stakeholders for In-situ trees conservation. The policy states as follows, biodiversity conservation and management will be included in the management plans for all protection forest. Involvement of local community and other stakeholders in conservation and management will be encouraged through joint management agreements (URT, 1998).All these police have their concern on farm trees but the difference arises on the aim and the extent of emphasis given. For instance the agricultural policy stresses on soil and soil fertility management, while in the forest policy the emphasis is given on forest biodiversity conservation. Furthermore there are some inconsistencies, the agricultural policies encourages livestock keeping on forested areas but at the same time there are problems of overgrazing that compromise the goal of the forest policy

4.3.2. Institutional linkages and farm land trees management

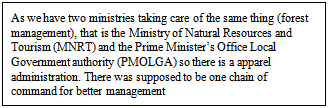

Policies rules and regulations do not operate on their own. In order for a policy to be implemented, rules and regulations need to be enforced. There are some legal aspects that have to act up on the matter[21]. For example the implementation of water policy is under the ministry of water at the nation level, catchments offices at the region and district level and it goes further down to the village level through water user associations. Moreover it also involves nongovernmental organizations such water Aid etc. Similarly there are also different institutions that govern forest/trees that are on farmlands. The institutions start from the individual person to the nationwide. Although it goes beyond the nation levels but this paper provide an analysis of the institutions up to a nation levels. It was observed that, there are different institutions that affect farmland management, and all the observed institutions implements policies set for forest management, for instance the agricultural policy (1997). Forest policy (1998) and the national environmental policy (1998) further more there are also local regulations that are implemented at a village level; the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, is responsible for all nationwide forest/tree such as those found in nature reserves, national parks and conservation areas. Nevertheless, extension services provided goes beyond the protected areas and it’s implemented through district forest officers. Unlike MNRT, the ministry of agriculture; that is responsible for farmland products was observed to have no explicit plans that support agroforestry instead the ministry have its newly formed department of environment. According to the ministry policy and planning office, the environmental department will be directing responsible for farmland trees not only for soil conservation but with concern to biodiversity conservation. The issue of institution linkages in managing farmland trees has a very good and significant chain from the farmer to the village to the district and up to the region levels. However, there is an institutional gap between the local governments and the central government in the management of trees. The MNRT legislation officer explained this matter in terms of priority giving during implementation of national policies and programs. The district forest officers are implementing the national forest policy but they are not answerable to MNRT, instead they are for the local government that is Prime Minister’s Office, Regional Administration and Local Governments (PMO, RALG). Because of this organization structure it has been difficult to implement some conservation activities under one chain of command. The district officers are responsible for local government priorities, along with that they also suppose to implement conservation activates. Nevertheless the district natural resources officer Mr. John said that the district had no explicit programs in agroforestry. This situation is also similar to the agricultural sector at the nation level; According to the district agricultural officer Mr. Mwezimpya, the district agricultural office has no explicit plans on farmland trees management. As it is for the local and central government on trees management issue, the coordination between the district agricultural and forest sectors is not well linked. Each unit is implementing its own activities. This was further stressed by the MNRT forest and bee keeping division, that they are facing difficulties in implementing some forest conservation activities through districts officers because their chain of command is from different ministry that is Local Government Authority. This implies that the trust levels between the two ministries are very minimal. Table 6. Forest legislation officer’s statement

|

| |

|

4.3.3. Market Linkages and Farmland Trees Management

According to the traffic report, Dar es Salaam is still the main market for forest products particularly timber. The case is different to the farmers, although they know where the major markets for their tree products are (mainly timber) but to them it ends within their village boundaries; moreover it is dominated by middlemen who act of behalf of farmers. This is because farmers are not capable of processing and transporting logs to other market places. Most of buyers are middlemen; it is these middlemen who control the market for logs in the villages. According to farmers in the focus interview; the logs bought from them by middlemen are brought to processing company within Muheza district and after processed the timber is taken elsewhere but mainly to Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar. Furthermore, internationally the timber is mostly sold in Asian countries especially China and India. For example for July 2005 to January 2006, 100% Swartzia madagascariensis was sold to China and 99% India for Tectona grandis (17, 20). Despite the good availability of market for timber products the farmer at the village level do not benefit from the efforts of taking care of the tree to the maturity. The main reason explained by the farmers is the low prices offered by buyers which leave farmers with no choices than selling their trees, price for teak (Tectona grandis) for example offered by buyers range from 3000 to 5000 Tshs, per a matured tree. ‘How can a tree which is more than twenty years old be sold for three thousands shillings, this is not fair.’ One of the farmers claimed on the prices offered to their tree products. This has been a very discouraging factor for trees planting and has led to selection of valuable species only leaving out fast growing tree species such as Grevillea. For the village located upland of the east Usambara they have a market advantage for Allan blackia. This is a native tree species favoured by the upland environment of the east Usambara Mountains; it is managed well by the farmers and from the institution that use it as a resource. This is the only tree product that has a well market arrangement from an institution. The farmers through organized groups collect and process Allan Blankia’s fruits and collectively take the product to village set market controlled by an institution named by Farmers as Faida Mali (Faida Market Linkages) when they collect the processed fruits farmers get paid through their groups. Like timber product and, the market chain for this fruit ends at the village, and the destination for this fruit was not identified by farmers. Faida have different activities in east Usambara. More than creating markets of Allan Blackia nuts, among others the following are some of the activities conducting market research to identify marketable produce for both national and international markets, Mobilizing and selecting farmers to produce the crop, designing and or commenting on the out growers contract developed by the buyer and translating the contract into the local language (for an agreed fee) Facilitation of meetings between company and farmers to discuss the enterprise and negotiate contract terms, When appropriate, assist participating farmers with tailor-made training in the areas of Business Awareness, Group Formation, Savings and Credit, and Keeping Farm Records.

4.3.4. Land Ownership Farmland Trees Management Nexus and Dependency Level of Forest Resources

4.3.4.1. Land Use, Ownership and on Farm Trees Management

Land is a very important resource[18, 19], as the population increases the need of land increase for different needs (Ibid), housing, grazing, cultivation etc. Along with these needs conservation of flora and fauna also utilize the same land. In east Usambara there are multiple land use systems; land for forest reserves both central and village forest reserves, plantation forests and tea estates. Further more the land for housing schools, health canters, play grounds, agriculture etc. These multiple land use in east Usambara competes against each other. For instance forest conservation (farmland trees) is intercropped with other crops while on, an average land size per household is about four acres and this is not constant to all the villages. Those upland villages have even lesser size of the owned land as they are closer to the nature reserve. However majority 46% own three acres and below, while 27% own between four and six acres, 12% own between eight and ten acres and only few 7% own more than ten acres. Although decision to plant trees in farmland results from different factors but there was no significant relation between the land size and the decision to plant trees in farms, but there was a relationship between land ownership status and on farm trees planting. Majority own land customarily as a result of traditional land ownership transfer (Inheritance), 91% of the respondents interviewed had no statutory land ownership. 62% own inherited land, 21% customarily own land they bought from local, while those who rent land are only 6%. There are also those who had land long ago by just clearing forest, these occupies 1% of the sample and those who were granted land by the village council counts for 10% of the sample.With all these characteristics of land use, land ownership as well as land size, aspects, a significant relation to farmland trees management is only manifested from land ownership, those who doesn’t have land at all and those who rent land have no intention on trees planting. Only 1% of those who rent land involve farmland trees planting while a significant 5% do not perform on farm trees planting. This is directly related to the ownership of land that one cannot invest in trees which takes 15-30 years to mature on land that is not permanently owned. There is also a very significant difference to those who own their land either statutory or customarily, many of them do plant trees in their farms, 68% do plant trees on their farms. This shows that land ownership has a great impact to trees planting. Great assurance of land ownership great probability of on farms trees planting

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Following this study local rules and regulations concerning the management of farmland trees were identified. Major policies and institutions governing farmland trees were identifies. These include National Forest policy (1998), National Agricultural policy (1997), and National environmental policy (1997). The extent of forest/trees resource use of the community was also identified, further the land tenure issues relative to farmland trees management were provided.The study found that the existing agricultural and forest policies are both complimenting the roles of trees on farm. However the emphasis on community practice of farmland trees is only given by the forest policy only. The agricultural policies just mention the aspect of promoting agroforestry without giving out strategies on how to implement it. Along with this, the study found that there is some inconsistence between these two policies. This is seen in their objectives, while the forest policies is aiming at promoting, maintaining and expanding forest cover the agricultural policy stress on increasing agricultural output and improving food security through expansion of farms. The study found that the bylaws set for forest/trees management in the study area are very effective and respected as being supported by private institutions like the Tanzania Forest Conservation Group and World Wild Fund.The role of farmland trees in people’s livelihood was also found to be of great extent as many household depends much of tree resources that are in their own farmland, this was proven by restricted/ limited accessibility to forest resources under reserve. The household results for example showed that 53% of respondent got their wild food (fruits) and vegetables from their farm trees.The study also found the existence of apparel administration in managing forest/ trees resources. The existence of MNRT and PMOLGA ruling at different levels brings overlaps and obstacles in implementation of forest policy. The misunderstanding that arises from this overlaps lowers the level of trust between MNRT and PMOLGA officers on forest/ trees management.

5.1. Recommendations

The need for forest/trees conservation is of great importance, similarly the need for forest resources are also very high and of great importance. There for consideration of both needs has to be taken into strong consideration. This study has found farmland trees significance as they serve for many and different needs of household in villages outside protected areas. The existing forest management regimes will be more significant if trees on farm are also put on board by being given a strong support both politically and financially. The notion brought by trees on farm is that when a household gets all the necessary trees resources needs the likelihood of encroachment to the reserves forest is also likely to be minimised hence forest and biodiversity conservation goals attained. Considering the market issue, strategies should be put to maximize market for other tree species; this will encourage more farmers to go for trees planting in their limited land. When this is achieved farmers will not only reduce pressure on protected areas but they will also have a way to sustainably improve their income. Furthermore harmonisations of policies are important so as to curb any opportunity for overlapping and publication of activities. This will help the set goals and priorities to be met in a spectacular act.Although the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism is responsible for forest extension services, private institutions such as Tanzania Forest Conservation Group and World Wildlife Fund appeared to play significant roles than the government institutions; however still the magnitude of services provided is not adequate. To make the extension significant the government and private institutions should work hand in hand to promote and encourage farm’s forest management. This should not only end at awareness creation but go further on provision of important equipments and techniques such as how and when to grow and take care of the trees. This move will increase both direct and indirect public participation in forest management hence achievement of targets on maintaining forest cover as well sustain current needs, furthermore improvement of people’s livelihoods will also be attained.

Notes

1. The description of the is available in http//www.easternarc.or.tz/eusam2. Biosphere Reserves are defined as areas of terrestrial and coastal ecosystems, which are internationally recognized within the framework of UNESCO’s Man and Biosphere Program and its global network, This has over 400 Biosphere Reserves. The basic idea behind these areas is to conserve the diversity of our living biosphere while, at the same time, meet the material needs and aspirations of an increasing

References

| [1] | Elsiddig E. A (in press) The Importance of Trees and Forests for the Local communities in Dry Lands of Sub-Saharan Africa, available atwww.etfrn.org/etfrn/workshop/degradedlands/documents/siddig.pdf, accessed on 14/11/2008. |

| [2] | World Bank 2000. Available at http://wbln0018.worldbank.org/news/pressrelease.nsf, www.fao.org/docrep/005/htn.Tree outside forest towards a better understanding, accessed on 30th September 2008. |

| [3] | ILO (2002). Available at, http://www.ilo.org . Accessed on 14/11/12 integrating crop and biodiversity management (2008), available at Biodiv_Leaf_20080207.pdf. Accessed on 17/06/2009. |

| [4] | FAO (2005). Global Forest Resources Assessment 2005 Forest paper 140. FAO, Rome. |

| [5] | Holopinen, Jani and Marieke Wit (Eds). (2008), Financing Sustainable forest Management. Tropenbos International, Wageningen, the Netherlands. Xvi + 176 pp. |

| [6] | IUCN (2003), protected areas category system. Available a www.unep wcmc.org/protected Areas/UN_list. On 28th September 2008. |

| [7] | URT, (1998), National forest policy. Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism |

| [8] | ECAPAPA (2005). Who’s Forest? Implications of Different Management Regimes for Sustainable Forest utilization and Minimization of Conflicts. Policy Brief No. 7. |

| [9] | Hermosilla. A.C (2000), The Underlying Causes of Forest Decline. CIFOR, occasional paper 30. |

| [10] | MNRT, (2007), Tanzania environmental profile. Available at, http; /www.mongabay.com, Accessed on 07/10/2008. |

| [11] | Watson, R. (2000), Report to the Sixth Conference of the Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Intergovernmental Panel on climate Change, Geneva, Switzerland.[Accessed 2008.] Available from http://www.ipcc.ch/press/sp-cop6-2.htm. |

| [12] | Leakey R. (1997), Redefining agroforestry – and opening Pandora’s Box? Agroforestry today 9:5. |

| [13] | Ashley, Russell. D &And Swallow, B, (2006), the policy terrain in protected area Landscapes: Challenges for agroforestry in integrated landscape conservation. ICRAF annual report 2006. |

| [14] | Machlis G.E. and Force J.E. (1997), the human ecosystem parts I: the human ecosystem as an Organizing concept in ecosystem management. Soc. Nat. Res. 10: 347–367. |

| [15] | Schroth G., da Fonseca A.B., Harvey C.A., Gascon C., Vasconcelos H.L. and Izac A.N. (Eds) (2004), Agroforestry and Biodiversity Conservation in Tropical Landscapes. Island Press, Washington DC. |

| [16] | Swallow B., Boffa J-M. And Scherr S.J. 2005. The Potential for Agroforestry to Contribute to the Conservation and Enhancement of Landscape Biodiversity. In Rebecca Mitchell and Michelle Grayson (eds.), World Agroforestry and the Future. World Agroforestry Centre, Nairobi, Kenya |

| [17] | Mathai. W, (2008), NGO alliance to tackle illegal logging. Available in http://www.traffic.org/home/2008/4/10/. Accessed on 7/10/2008. |

| [18] | EUCAMP (1998), Programme/Project document phase III: 1999 – 2002. Tanga Eastern and Central Africa Programme for Agricultural Policy Analysis. |

| [19] | Mbeyale, G.E., (1999), Socio-economic Assessment of the factors influencing building poles Consumption, conservation and management of Amani Forest Nature Reserve. Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (Forestry) of Sokoine University of Agriculture. Morogoro: SUA. |

| [20] | Roberts (1995).The quest for sustainable agriculture and land use, University of south Wales Press LTD. Sydney Australia |

| [21] | Kabudi k.j (2005) Challenges of legislating for water utilization in rural Tanzania; drafting New laws. International workshop on African water laws; plural legislative framework for rural water management in Africa, 26-28 January, 2005, Johannesburg, South Africa. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML